On December 1, 2020, with the holiday season approaching and the latest congressional stimulus package stalled, The Washington Post reported that “about 26 million Americans say they don’t have enough to eat as the pandemic worsens.” The Post recommended several organizations to which readers could donate, including charities and philanthropies for artists and restaurant workers, for children facing hunger or without access to books or the Internet, for asylum seekers, and for the many in need of food, shelter, and personal protective equipment. It is, of course, in moments of crisis that the plight of the neediest becomes most dire, just when resources are scarcest.

Who deserves our support? Whether we ask the question as private individual donors or as taxpaying citizens, the answers reveal our values and identities. The distribution of aid is “an essential aspect of the formation of a community,” Debra Kaplan notes in The Patrons and Their Poor: Jewish Community and Public Charity in Early Modern Germany, and the decision as to who is eligible to receive it helps define who belongs and who does not.

Some people in poverty turn to publicly available resources; some, in desperation, turn to strangers by begging. Although today municipalities like New York City, Niagara, and Yonkers seek ways to ban or at least restrict public begging, the practice is not illegal in the United States. In 1980 the Supreme Court ruled in Schaumburg v. Citizens for a Better Environment that solicitation for money was protected by the First Amendment. Though the case dealt with an organization, the principle was subsequently applied by other courts to protect panhandling as well. And in December 2020 the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court became the latest to strike down “a state law making it illegal for people to ask for money for their own support on public roads.”

The questions about poverty and charity we are facing now, in the middle of a major economic and public health crisis, are not new. They reflect our moral values as well as our social, legal, and political structures. (Tellingly, in the US, charitable giving is intertwined with tax codes.) To be sure, these values do change over time and vary across regions and cultures. In Judaism, tzedakah—roughly, charity—is a moral obligation, a mitzvah. (Although a mitzvah is also considered a good deed, in Hebrew it means a religious precept or commandment.) “Formal institutions for poor relief,” not just individual almsgiving, Kaplan writes, were already “prescribed” in the Mishnah and the Tosefta—ancient Jewish texts from the second and third centuries CE. Zakat, or almsgiving, is one of the Five Pillars of Islam.

In Christianity, by contrast, charity is not a commandment or a pillar of religious practice, though Jesus’ teachings about poverty and wealth have played an important part in the development of Christian views on charity and on the role of the poor within society. In Christian medieval communities, for example, poverty was not considered shameful. Quite the opposite: poverty as a voluntary way of life was seen as a manifestation of piety, embodied most famously by Saint Francis of Assisi and the members of mendicant orders. In the seventh century Saint Eligius reportedly said, “God could have made all men rich, but He wanted there to be poor people in this world, that the rich might be able to redeem their sins.” The poor begging at church entrances were a common sight, offering the wealthy an opportunity to give alms. Even the word for “hospice” suggested an aura of holiness. In Paris, it was Hôtel-Dieu, and among Jews of Northern Europe it was called a hekdesh, related to the Hebrew root for “holy,” k-d-sh.

Then, Kaplan notes, echoing the historian Thomas Max Safley, “something happened to charity in early modern Europe.” In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, crop failures led many of the rural poor to move to cities. Frequent epidemics overwhelmed local hospices, and religious individuals and institutions alike were unable to provide adequate support to the sick and the poor. More formal solutions were needed, and almsgiving and poor relief became increasingly regulated. Now the poor were no longer seen as a means of redemption for the rich but as a public nuisance and a social burden, and perhaps as a vector of disease.

The cities began to define who was deserving and undeserving of aid. Public begging was increasingly banned, poverty was gradually criminalized, and residency was required to qualify for poor relief. In 1516, for example, Paris banished “vagabonds.” Nearly two decades later the Paris parlement, a judicial court, issued strict regulations of poor relief: “On pain of death,” able-bodied beggars born in Paris or residing in the city for at least two years had to “present themselves for employment at public works.” The city set the rate of their wages. Those who were not born or legally residing in Paris were forced to leave the city within three days, also on pain of death. The disabled poor were eligible for aid, funded by taxes collected by the city since 1525. But those who feigned illness or disability were to be flogged and banished. The regulations did not just ban begging; they also banned giving alms “in the street or in a church,” and violators were fined. So the city took over relief of the poor, and by its standards, Saint Francis would have likely been considered a “vagabond” and cast out. These harsh measures were the sixteenth-century version of “welfare-to-work” programs aimed at curbing the cost of poor relief by encouraging work and discouraging “idleness.” This was a major shift from the medieval perception that glorified and even encouraged voluntary poverty as an act of piety.

Advertisement

To support poor-relief programs, in the sixteenth century the authorities sought sources of revenue, in cash or in kind. While almsgiving tended to be personal and voluntary, poor relief increasingly became communal, paid for by tax revenue and gradually developing into bureaucratized social welfare programs, with rules and regulations. These helped define who belonged to a community and who was an outsider. In Christian society, the Reformation only accelerated the process, as charity, formerly “a provenance of the church,” became the responsibility of secular authorities.

Two recent books examine poverty and charity in European Jewish communities, looking at how a marginalized minority dealt with the problems of destitution and social welfare during periods of rapid change. Kaplan’s The Patrons and Their Poor, a study of three major Jewish communities in German lands—Frankfurt, Altona-Hamburg, and Worms—during the early modern era, examines the momentous transformations in Europe that affected the distribution of poor relief and recast poverty as a social problem rather than a pious act. Natan Meir’s Stepchildren of the Shtetl explores cultural shifts in attitudes toward “the destitute, disabled, and mad” in Jewish communities in Eastern Europe, predominantly in Russia and Poland, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Medieval and premodern European society was organized into legally defined estates; Jews were one such estate. Each municipality, estate, city, or community was responsible for its own laws and finances, and so were Jews. Their legal autonomy extended over most matters in their own community, such as court cases between Jews, tax collection, and the distribution of resources, including poor relief.

But this autonomy was not absolute. Jews, after all, lived in a majority Christian society, and at times Jewish self-government was enforced by Christian authorities, who wanted to make sure that the political and legal boundaries were retained. Kaplan writes that in Frankfurt, for example, Jewish leadership issued regulations concerning arbitration “after the municipal authorities complained that too many Jews were approaching them to seek justice.” The authorities wanted the Jewish community “to handle these issues on its own.”

Jews were marginalized within European Christendom, and like any minority community they were affected by changes in the dominant populations. As poor relief began to change in Christian communities throughout Europe, Jewish authorities responded similarly. They began to restrict begging by issuing licenses to beg door-to-door only to those poor they considered “deserving”—that is, those who could not work. Any other kind of begging was banned, as were almsgiving and aid. But once individual almsgiving and begging were restricted and authorities took over poor relief, those same authorities had to pay for it, and so they enforced the new statutes with fines. In Hamburg and Altona, for example, anyone who “house[d] a guest who was a beggar” was fined. Community leaders, in part due to limited resources, also restricted sustained poor relief to legal residents only (the “poor of our city”) while providing only temporary relief to transient poor (“foreign guests”), who were then forced to leave after a day or two. But the commitment to the local poor was impressive, covering, in Kaplan’s words, “rent, taxes, food, medical care, and holiday purchases.” The standard for food was three meals a day. All this required meticulous record-keeping and the issuance of residency rights and begging permits, which made the process more institutionalized and bureaucratic.

Assessing need became another task of the communal authorities. A passage in Deuteronomy (15:8) directed that a person in need should be provided aid “sufficient for whatever he needs.” The medieval rabbi Rashi added that one should not expect to make the needy person rich, but that if they had been rich before falling on hard times, “you must provide him even with a horse to ride on and a slave to run before him (if he was accustomed to such and now feels the lack of them).” This understanding was accepted among Ashkenazi Jews for centuries, as testified by the seventeenth-century community official Juspe Schammes of Worms, whose record book Kaplan uses extensively. But when poverty increased, this kind of commitment was potentially burdensome for the community, and could result in deficits.

Advertisement

Then there were the donors. As today, philanthropy in premodern communities was the domain of the wealthy; Kaplan notes that “only those of an elite social status were appointed as charity collectors.” To be among them was a mark of station, and with it came honors, including special parties and banquets, at some of which were served “cooked foods, roasted meat, and good things,” though at others honorees only received “wine, soup, and two eggs.” Kaplan describes the rituals of honoring the benefactors through both “heavenly and earthly forms of recognition”; their names were recorded in community Memorbücher and subsequently recited on “almost every Sabbath,” and “liturgical blessings [were] performed publicly” for their benefit. Donors could be shamed, too. When a community leader in Frankfurt went bankrupt, he was excluded from the annual blessing of the donors—“an extremely visible and humiliating sanction,” Kaplan writes. She convincingly shows that “rituals of charity were thus designed to preserve hierarchies between donors and the poor.”

Indeed, sometimes donations were forced, as Kaplan writes: “Taxes were frequently used for charitable ends, and charity was often collected in an obligatory, tax-like fashion.” In Frankfurt, Jewish community leaders ordered that “whenever a couple would marry, each side of the wedding party was to donate to the community a quarter gulden from the dowry.” And in Worms and Altona-Hamburg parents could not marry off a child, and a widow or widower could not remarry, “unless they had paid all their tax and charity obligations to the community.” Donations could also be given as penalties for transgressions. With no broader state structures and safety net in individual Jewish communities, charity was “an indispensable part of the larger economic system.”

While Kaplan uses charity and poor relief to walk us through the inner workings of early modern Jewish communities, Natan Meir’s Stepchildren of the Shtetl takes us to the “darkest and most sinister aspects of Jewish society” in Eastern Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, exploring the increasing pauperization caused by demographic growth, industrialization, and urbanization. His book exposes what socially marginalized people reveal about the larger collective.

Majority communities often conflate minority groups with their most destitute members: the poor, the criminal, the rejected, the mentally ill, the addicted—in short, “the undesirable.” The marginalized become, in the eyes of the majority, the synecdoche for the minority itself. And because the social “undesirables” are made to stand in for a minority, they constitute a threat to that group’s respectability; as one scholar quoted by Meir put it, they become “a threat to honorable people.”

In her book Dark Mirror (2014), about the origins of anti-Jewish iconography in European art, the historian Sara Lipton shows that medieval Christians did portray Jews as ugly, deformed, and scorned, and later came to see them that way. Such visual representations supported their view of Jews as having been rejected by God for their denial of the truth of Christianity, thus justifying their social marginalization and subservience. In the premodern era, however, Jews were specifically not what they were portrayed to be—they were fairly affluent, though there were poor among them; they had autonomy and access to power, though they were vulnerable.

Yet with increasing pauperization in the modern era, especially in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Eastern Europe, the image of the ugly and despised Jew of Christian iconography became embodied in real-life Jewish paupers. As Meir notes, “the actual deformities of disabled Jews thus echoed long-standing Christian superstitions about Jewish bodily anomalies (e.g., the Jewish hunchback) embodying Jewish immorality.” The highly educated elite Jews who self-consciously desired to belong to mainstream European societies now became more aware and more bothered by the overwhelming visibility of those Jews pushed to society’s margins. Indeed, among Jews, Meir writes, “while marginals were sometimes among the most conspicuous people in a town—who could ignore the rantings of a town fool or the insistent pleading of the local beggar?” they were the ones whose existence Jewish society did not want to acknowledge, in part because they threatened the standing of the community as a whole.

But historical sources are not written by those Meir calls “outcasts.” Records might inform us of their existence, but regulations, statistics, and donation amounts can tell us only so much about how they lived. Kaplan and Meir both turn to cultural sources to shed light on the experience of marginalized Jews. The American intellectual and theoretical historian Hayden White once said that historians are translators of “facts into fictions,” but here the writers do the opposite: they seek to historicize fiction to complement what we know of the facts.

Kaplan cites a song from Frankfurt, popularized in 1708, that captures the interaction between “gatekeepers and the poor.” The lyrics single out a gatekeeper, Jacob Fulwasser: “When we poor guests march to Frankfurt/People do not allow us to stay at their doors./Here comes Jacob Fulwasser with his cane to hustle us away/And lead us, one by one, into the guardhouse.” In the winter, Fulwasser would do “much worse, treating the poor cruelly./He leaves us, large and small, to stand in front of the gate,/And allows no one to approach the charity collectors until our hands and legs have frozen./We cry out in pain.”

In his own discussion of novels, short stories, poems, songs, and plays, Meir reveals the instinct of more fortunate Jews to reject and scapegoat “outcasts.” After Tsar Nicholas I introduced a harsh regime of conscription in 1827,

some Jewish communal leaders, compelled by the state to compile lists of draftees, attempted to draw recruits solely from among socially marginal people. Other Jewish communities drafted poor orphans as so-called voluntary substitutes for the sons of prosperous families.

In 1828, in Grodno, the kahal, or Jewish community board, sent as recruits “people the community could not tolerate”—the “idlers” and those who did not pay taxes. Popular songs and tales captured this phenomenon. One song told of a poor widow’s son who was taken as a recruit to the tsarist army in place of the son of a more prominent community member. The widow’s son was “a scapegoat for the kahal’s sins,” while the “brutish kids from a prosperous family/Can never leave their families, not a one.” Meir concludes that the castoffs were “victims of the immoral choices of society.”

As the song about the widow’s son shows, there was a still more symbolic, and more disturbing, understanding of the sacrificial functions that these communal “outcasts” had in Eastern European Jewish society. In moments of crisis, the poor were offered as atonement for sins of the community—to forestall a disaster. Meir devotes a great deal of attention to the so-called cholera wedding, a “hoary rite” developed in the mid-nineteenth century, when the first epidemic of cholera hit Russia:

Two or more of the poorest and most vulnerable members of the community were matched with each other and married at the cemetery or on the outskirts of town in an uproarious celebration attended by a good proportion of the town’s residents.

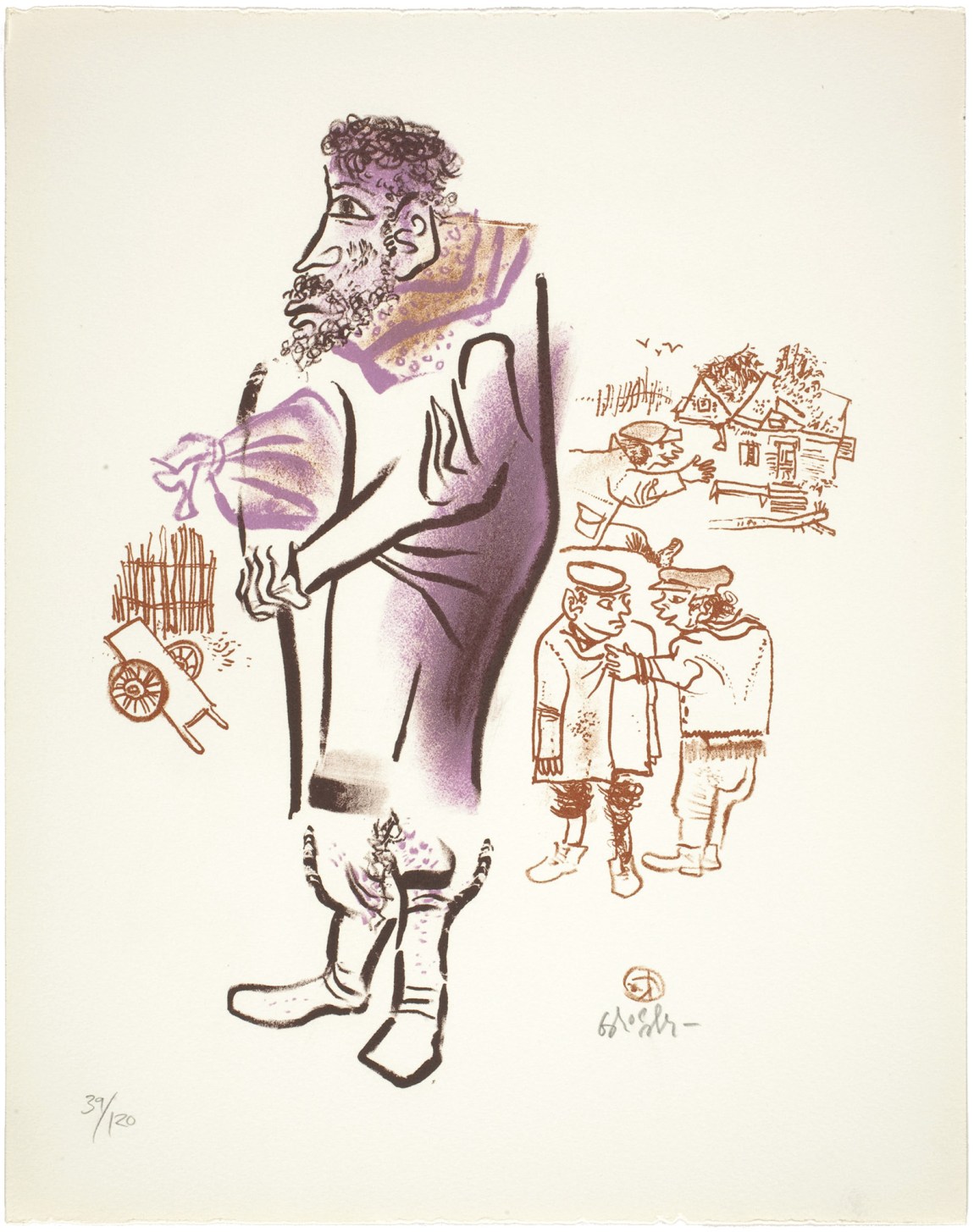

Such a humiliating ceremony was necessary, one nineteenth-century writer noted in a story, for “the salvation of the town.” A famous Yiddish writer, Sholem Abramovitsh—best known for the character Mendele Moycher Sforim, Mendele the Bookseller—described such a wedding in his 1869 novel Fishke the Lame, which was adapted for the screen in 1939:

Before an assemblage of fine Jews at the cemetery, the fool placed the bridal veil on the head of a girl, a head that had already been covered since childhood because of—pardon the expression—its crown of cankerous sores, and about whom it was rumored that she was a hermaphrodite.

As Meir explains, “Abramovitsh’s cholera brides and grooms are meant to disgust the reader with their bodily protrusions (shovel teeth) [and] repulsive convexities (mouth without a lower lip, cankerous sores).”

The cholera wedding reveals something deeply distressing about a society’s willingness to mortify its most vulnerable members. Meir’s book can be read as a warning about the human ability to marginalize and sacrifice others. And though Meir does not take up that point, the nineteenth-century literature he discusses captures a cultural shift about the meaning of sacrifice. The book of Leviticus (22:20–22) instructs Jews that any offering to God should have no defect, for if it did,

it will not be accepted in your favor. And when a man offers, from the herd or the flock, a sacrifice of well-being to the LORD for an explicit vow or as a freewill offering, it must, to be acceptable, be without blemish….

Anything blind, or injured, or maimed, or with a wen, boil-scar, or scurvy—such you shall not offer to the LORD.

The cholera wedding was an inversion of that. Those married in a cholera wedding, offered by the community to ward off an epidemic or another disaster, were exactly what God prohibited—blind, injured, maimed, and covered in boils. But that was precisely why they were selected. The members of modern society were no longer willing to sacrifice what was most valuable to them.

Both Kaplan and Meir reveal the distance, real or desired, that societies have created between those in need and the rest. As Meir notes, it is easy to click a “donate” button on a website, but much more difficult to interact with the people society casts out. Today, we too have institutions to deal with social problems. In New York one can call 311 to report a homeless person and let the city deal with their plight. But in the premodern period, the poor were sometimes housed by community members, or at least fed by them. With time, institutions of poor relief became more bureaucratized, increasingly removed to the margins of towns. In Eastern Europe they were often near cemeteries and presented, as the English missionary Robert Pinkerton remarked in 1833, “one of the most appalling scenes of wretchedness.” Likewise, today homeless shelters are placed in poor, disenfranchised neighborhoods, sometimes in abandoned, isolated, postindustrial parts of cities. Otherwise there is an uproar from residents in more affluent neighborhoods who refuse to accept the poor and marginalized in their midst—a manifestation of their beliefs regarding who belongs and who does not. The association of holiness that such places housing the poor held in the Middle Ages is lost.

Charity helps define a community, as Kaplan and Meir demonstrate, and it seems significant that in the United States many Jewish charitable organizations, which were established specifically to help the Jewish poor or support Jewish causes, have now expanded their scope to support social justice more widely. According to Hanna Shaul Bar Nissim, a scholar of Jewish philanthropy, Jews contribute as much to outside causes as parochial ones, in contrast to other religious groups. In the Covid era, as she and Jay Ruderman, a lawyer and philanthropist, have noted, the giving from Jewish Community Federations has similarly reflected “their inclusive approach to serving the needs of those most affected by Covid-19, one that transcends traditional community boundaries.” These findings are a striking sign of a broader sense of communal belonging among Jewish Americans.

In his book Free World (2004), Timothy Garton Ash remarked, “When you say ‘we,’ who do you mean?… What’s the widest political community of which you spontaneously say ‘we’ or ‘us’? In our answer to that question lies the key to our future.” The question is as salient today as it was in early modern Germany and in nineteenth-century Eastern Europe. Our generosity and empathy as individuals, as communities, and as nations, especially in this time of crisis, may reveal the answer.