The art critic Harold Rosenberg is remembered as a swashbuckling player in a sprawling American intellectual drama—a sort of epic family romance—that extended from the 1930s to the 1960s. The Old World was fading, the New World was taking center stage, and many American artists, writers, and thinkers were eager to celebrate what they saw as New York City’s intellectual and cultural dominance. The works and days of Rosenberg’s unruly cohort—which included friends now far more famous than him, among them Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, Saul Bellow, and Mary McCarthy—have some of the fascination of a genesis story.

We are drawn to the complications and controversies of those times, whether the personal lives of de Kooning, Bellow, and McCarthy or the violent split among New York intellectuals that Hannah Arendt, another friend of Rosenberg’s, precipitated with her report on Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem. Rosenberg was in on the action, jazzing up the new art with the striking catchphrase “action painting” and provoking another critic, Clement Greenberg, to take aim at him in an essay entitled “How Art Writing Earns Its Bad Name.” The disagreements between these two men have a primal resonance. By some reckonings Greenberg (the formalist) and Rosenberg (oversimplified as the antiformalist) are as entangled as Cain and Abel.

Rosenberg, who at the time of his death in 1978 was a regular contributor to The New Yorker and a member of the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago, was fascinated by the paradoxes that plague the discerning mind. He was skewering the delusions of his own rowdy crowd as well as the culture industry more generally when he coined one of his most winning phrases, “the herd of independent minds,” as the title for an essay published in 1948. But the essay didn’t necessarily fulfill the title’s promise. Was he saying that intellectual independence was an illusion? Or was that clever takedown just his way of navigating a time of peril and possibility, when artists and intellectuals were finding their bearings after two world wars, the Holocaust, and the rise of authoritarian regimes on the right and the left?

More than half a century later, as we confront our own diminishing prospects, we may be right to believe that our troubles began back then. True, it was a period of American optimism, but the boom times were shadowed by a gathering awareness that the faith in human progress that had emboldened nineteenth-century thinkers was failing. No wonder there has been so much interest in recent books that cover those years, including Louis Menand’s The Free World, Benjamin Moser’s biography of Susan Sontag, Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women, and Mark Greif’s The Age of the Crisis of Man. Two new additions to this literature—Debra Bricker Balken’s Harold Rosenberg: A Critic’s Life and Edith Schloss’s The Loft Generation: From the de Koonings to Twombly—provide a few more close-ups of the mid-twentieth-century drama.

In The Loft Generation, Schloss recalls de Kooning complaining “that Marx and Freud and Einstein had led us astray.” Those were the words of a man who, however engaged he was with what Rosenberg dubbed “the tradition of the new,” also had his doubts about modernity. As for Rosenberg, who had embraced Marxism in the late 1920s and never entirely escaped its influence, he might be described as a disabused optimist. Schloss, a painter and writer who for some years was part of New York’s downtown art scene, offers quick, penetrating portraits of Rosenberg and de Kooning, as well as the dance critic and poet Edwin Denby, the painter and critic Fairfield Porter, and the poet and critic Frank O’Hara. Although her memoir, which was left unfinished at her death in 2011, is by no means a success—Schloss doesn’t make herself enough of a protagonist—along the way she provides the striking glimpses of midcentury life and thought that are missing in Balken’s biography of Rosenberg, the most extensive study of the critic to date. Instead of sharpening our sense of Rosenberg, whose writing McCarthy praised for its “zestful freedom” and “gleeful boyish” energy, Balken loses focus as she weaves from one old intellectual controversy to another.

I realize that the intellectual and imaginative achievements of postwar New York resist easy summary. What I think it’s safe to say is that there was a recoil from the all-encompassing visions of human history that had thrilled artists, writers, and thinkers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For a time the collapse of Marxist orthodoxies saw many intellectuals turning to Freud or existentialism, but mostly in a search for personal rather than communal answers. The rejection of big ideas could be a good thing, when it led to fresh, more sharply focused observations and insights. Or it could be a bad thing, when it pushed people to reject any system or idea, however promising.

Advertisement

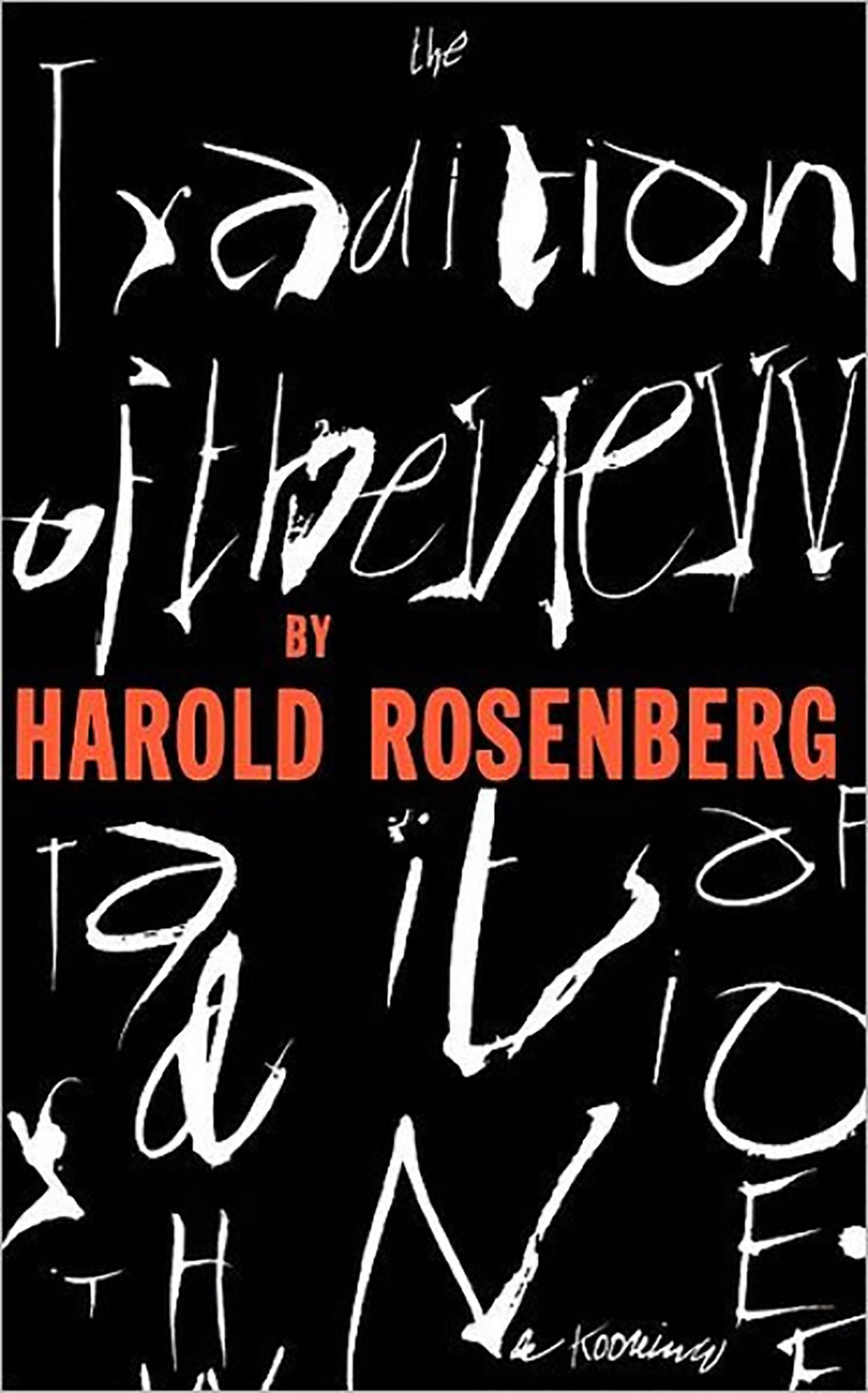

De Kooning, a central figure in Schloss’s memoir, dismissed the grandiose theorizing of Kandinsky and Mondrian, although he very much admired their work; he wanted to operate from instinct. Rosenberg’s first essay collection, The Tradition of the New, was graced with a brilliant jacket design by de Kooning (see illustration below). The critic was eager to align himself with the artists he admired and who, as Schloss recalls, had already “freed themselves from the pieties of social consciousness” but were willing to accept some of his thought even though it “was colored by Marxist logic.” Rosenberg was always trying to reimagine the grandiose theorizing of an earlier age in a more fluid and contemporary form.

Harold Rosenberg was born in 1906 in Brooklyn. He attended public schools in New York and received a degree from Brooklyn Law School in 1927. By the time he was in his twenties he was a striking presence, tall, with dark hair and eyes and dramatic features. In time he became “a regal person,” Bellow recalled in a memoir written after his friend’s death. Rosenberg’s father, Abraham, who had immigrated from Poland, was a tailor, an observant Jew, a Zionist, and according to his son a man “devoted to literature, ideas and study.” On Sundays he took Harold and his brother, David, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Although Rosenberg, according to Balken, had little feeling for Jewish life, whether the synagogue or the Zionist cause, he later wrote about “the fantastic emotional residues of the Jewish family.” Some ancient, biblical sense of the individual as an actor in history, mediating between tragedy and triumph, must have helped propel him to the not inconsiderable place he held in intellectual life in the 1960s.

Rosenberg’s early years bring to mind the struggles of another young man, Alfred Kazin, as he described them in two masterpieces of memoir, A Walker in the City and Starting Out in the Thirties. Both men, even as they grappled with the deprivations and austerities that their working-class families knew all too well, found an outlet for their dreams of glory in the literature, art, and ideas that were available to just about any New Yorker with a subway token and a library card. Balken’s book opens on the steps of the New York Public Library in the summer of 1928, where Rosenberg found himself talking with Harry Roskolenko, a writer who never became well known but immediately impressed Rosenberg with his talk of Marx and his followers. The library steps, Roskolenko wrote in a memoir published after Rosenberg’s death, were “our Roman circus and our Greek forum.”

The scene, as Roskolenko described it, had a madcap intellectual exhilaration, with a range of characters including Kenneth Burke, a formidable literary critic too little read today, Sidney Hook, the bold philosophical thinker who moved from principled leftist to principled conservative, and an assortment of “philosophers, critics, grammarians, Marxists, Trotskyites, Stalinists, technocrats, vegetarians, free lovers—everybody with a talking and a reading mission.” If that wasn’t enough to excite a young man, Rosenberg’s brother, an aspiring poet, had already embraced life in Greenwich Village, where Harold became familiar with the work of Stravinsky and Schoenberg and modern writers, among them Stein, Joyce, Gide, and William Carlos Williams.

It wasn’t until the early 1950s, with the publication of “The American Action Painters” in ARTnews, that Rosenberg really became an art critic. Before that he moved in downtown New York’s overlapping literary and artistic worlds, a figure of some significance but without a clear direction. He did some editing and writing, published a book of his poems, and worked on the WPA American Guide series. During the war he was involved, in both Washington and New York, with the Office of War Information, and at the end of the war he found a job with the American Ad Council. Balken has brought together a considerable amount of information about Rosenberg’s contributions, as author or editor or both, to a range of magazines, many never well known and some hardly known today, including Poetry, Art Front, Partisan Review, View, VVV, Possibilities, and Location. She plunges into the tangled leftist politics around Art Front and the rival Surrealist camps that fueled View and VVV, and explains why Possibilities, which Rosenberg edited with Robert Motherwell, lasted only one issue and Location, which he edited with the critic Thomas B. Hess, only two.

Balken, a well-regarded art historian and curator, seems overwhelmed by her material. By the time I closed her book I felt that I’d learned more about the politics of Artforum, a magazine with which Rosenberg was only tangentially involved, than about his marriage, his daughter, or his death. She relates some of the bickering and backbiting that characterized the art community on Long Island; the Rosenbergs bought a house near East Hampton and spent many summers there. But she doesn’t make good use of But Not for Love, a novel by Rosenberg’s wife, May Natalie Tabak, the early pages of which evoke the beauties of life away from the city: a couple could be “stretched out on the sand, reading and drowsing until the tide went out,” gather clams as they walked home, and then cook them while burning “dead branches of an apple tree in the fancy parlor stove with its proud German silver trimming.” What’s missing in Balken’s biography is the joy—maybe even the romance—of New York artistic, literary, and intellectual life.

Advertisement

Rosenberg, Balken would have us believe, was a perpetual outsider—a man who “always resisted the in-crowd.” I’m left wondering how she reconciles this with his later years, when he was on the faculty of a prestigious university and had a permanent post at one of the country’s most important magazines. Balken loses sight of the man whom Bellow, in his magnificent story “What Kind of Day Did You Have?,” reimagined as Victor Wulpy, “a major figure, a world-class intellectual.” Bellow’s eminent art critic hobnobs with financiers and knows his way around café society. Perhaps there’s an element of hyperbole in Bellow’s fictionalization. Nevertheless, if Rosenberg can be described as an outsider, it’s only because in the 1960s a little antiestablishment cred didn’t hurt if you were aiming for a place on the inside track.

Rosenberg was forever shaped—and reshaped—by the social upheavals and Marxist and socialist thought that had dominated his younger years. But in the face of the Stalinist trials and purges of the 1930s he rejected, as did Greenberg, Dwight Macdonald, and others in the circle around Partisan Review, the Soviet view of an artist or a writer as a disciplined representative of a cause. Rosenberg wanted to free the artist from all social constraints; he believed that was in line with Marx’s concept of the artist as representing “the liberation of work.” For a time Rosenberg and his friends put great store in the writings of Trotsky, who from Literature and Revolution, published in the 1920s, through some essays produced in his final years of exile had refined and extended Marx’s ideas, arguing that artists must be left to pursue their own dreams.

Years later Greenberg acknowledged the impact of Trotsky’s ideas on the artists and intellectuals of his generation, suggesting that “some day it will have to be told how ‘anti-Stalinism,’ which started out more or less as ‘Trotskyism,’ turned into art for art’s sake.” But there was a catch in Trotsky’s version of artistic freedom, one that I’m not convinced either Greenberg or Rosenberg or anybody else in the Partisan Review circle ever quite resolved. Trotsky believed that the artist’s insights, however freely achieved, were important because they revealed the nature of society—and thereby helped clarify the direction that the revolutionary struggle had to take. If Trotsky made it possible for Rosenberg and others to reject any mechanistic equation when it came to the artist and society, the old Bolshevik nevertheless left them feeling that a creative spirit’s relationship with society had to be nailed down, in one way or another.

In Greenberg’s most famous essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” the rise of kitsch, with prepackaged images engineered for mass consumption, pushes the most original artists into an Olympian escape—an increasingly isolated position. It’s as if society’s impurities force the artist to seek purification. In “The American Action Painters,” the essay with which Rosenberg will forever be associated, the artist makes another kind of escape. The Marxist or socialist emphasis on taking action in society is transformed into a different kind of action: the artist acts (maybe even acts out) on the canvas. A brief paragraph has become notorious:

At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act—rather than as a space in which to reproduce, re-design, analyze or “express” an object, actual or imagined. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.

Action, the watchword of so many of Rosenberg’s political friends in the 1930s, remained, but the arena in which the action occurred was no longer the wide world but the enclosed space of the artist’s studio.

“The American Action Painters” is a strange essay, composed not in a single arc but in fragmentary sections with subtitles including “Getting Inside the Canvas,” “Drama of As If,” and “Apocalypse and Wallpaper.” It suffers from a problem more general in Rosenberg’s essays. He had a genius for the telling phrase and the provocative sentence but had more trouble when it came to building from striking observations to broad conclusions. My feeling is that once he’d come up with the action painting idea he didn’t really know where to go with it. His literary gifts can seem scattershot. Macdonald wasn’t entirely mistaken when he observed of Rosenberg’s “most epigrammatic and gnomic style” that “if he could just once develop a point, he’d become a serious writer.”

Nobody has captured both the highs and the lows of his work better than McCarthy, in her review of The Tradition of the New, which included “The American Action Painters.” She admired Rosenberg’s energy and vigor but was too clear-eyed to accept his rather melodramatic account of the act of creation. I worry that Balken, swept up by McCarthy’s almost comic good cheer, does not fully grasp the devastating conclusion of this otherwise genial salute to a friend. “You cannot hang an event on the wall,” McCarthy wrote toward the end of her review, a comment that punctured all the drama of Rosenberg’s essay. Art, she was saying, wasn’t activism.

In the years before his death, when he was the art critic for The New Yorker, Rosenberg’s writing became more disciplined and more conventionally structured. William Shawn, the magazine’s editor, must have encouraged greater transparency, which was all to the good. The essays from The New Yorker collected in The Anxious Object (1964), Artworks and Packages (1969), and Art on the Edge (1975) remain a considerable contribution to the historical record. Rosenberg was something of a master when it came to documenting shifting trends and taking the temperature of the art world. But even when he wanted to experience a painting or sculpture for itself, he couldn’t help slipping into socio-philosophical mystifications. Artistic individualism was always becoming something else—protest, alienation, estrangement. “If politics haunts post-war painting,” he wrote of one of the artists he most admired, “de Kooning haunts the ghost.” De Kooning, he continued, “is the nuisance of the individual ‘I am’ in an ideological age.” His “art is a refusal to be either recruited or pushed aside.” We are back to the artist as actor—but now a ghostly actor. As for Barnett Newman, another one of Rosenberg’s enthusiasms, his “art must remain partly inaccessible. It belongs to a one-man culture, which as it becomes more integrated becomes more estranged from shared ideas.”

I can forgive Rosenberg his conundrums. What I can’t forgive is his pride in his conundrums. He’s so caught up in his own speculative pyrotechnics that he can’t or won’t let himself believe that a work of art has a freestanding value. He thinks more than he feels. His intellectuality overwhelms his avidity—and that’s disastrous for a critic. While he waxes enthusiastic and even lyrical about particular artists, from his beloved Abstract Expressionists to the work of his good friend Saul Steinberg, what’s missing is some sense of what he really wants or demands from the work of art itself. A reader can disagree with practically everything that Greenberg ever wrote about art but still come away from his writing with an exhilarating feeling for his sensibility—for what Greenberg wanted or even needed from art. With Rosenberg that fever, those hot likes and chilly dislikes, aren’t there. He was a great personality—Bellow turned that personality into Wulpy, an unforgettable character—but in Rosenberg’s own writing his personality doesn’t emerge, at least not fully enough.

Rosenberg’s overintellectualization has led his biographer astray. Balken is so busy nailing down this or that argument or alliance that she misses the lust for debate that consumed New York’s artists and intellectuals, even when they weren’t sure where the argument was going or how it could ever be resolved. You feel that wild hunger in McCarthy’s memoir of the 1930s, the brilliant Intellectual Memoirs, where at some point the disagreements about Stalinism and formalism get so tangled that it’s not clear to her where anybody stands. Denby, one of the central figures in Schloss’s memoir, wrote that in the 1930s he and his downtown New York friends were relatively uninterested in Marx’s ideas but could not help but feel “the peremptoriness and the paranoia of Marxism as a ferment or method of rhetoric.” The energy of dispute sometimes seemed more important than the nature of the dispute. Without understanding that, you can’t understand Rosenberg.

Schloss’s memoir catches some of the heat of those times. She’s very good on Rosenberg’s wife. Like her husband, Tabak “had a big air about her.” With her

jagged features and a wild black mane, in black caftans and swinging beads—[she] was more flamboyant than he was. At their lively parties in their first-floor apartment near St. Mark’s Place, there reigned the high, thin air of intellectualism and a fervid faith in abstraction.

Schloss, who was married for a time to Denby’s closest friend, the photographer and painter Rudy Burckhardt, is an unsentimental romantic. Students of dance and poetry will be especially interested in her portrait of Denby, whose reputation as a downtown secular saint she complicates with suggestions of misogyny and passive-aggressive behavior. She’s anything but dismissive of him, evoking with affection the “slim, elegant man” who lived in a loft that was “a long, white, softly shining place.” And she’s obviously sympathetic with the apolitical orientation of this writer who, after embracing modern dance in Germany, “found Bill [de Kooning] and Balanchine in America. One was about power, the other about grace.” But Schloss can’t forgive Denby for using his platonic intimacy with her husband to unhinge her marriage. It was the ambiguities of Denby’s personality that must have led Anne Porter, the poet who was married to Fairfield Porter, to observe that “Edwin will make you see the justice in injustice.” The bohemian celebration of personal freedom could lead to a free-for-all that left some as trapped as anybody ever had been by the old morality.

De Kooning comes to life in Schloss’s flashing sentences: “Small, dapper Bill was always attractive to women. His curtness, his no-nonsense comebacks, the humor lurking in his eye, his quick, precise, small movements, his work clothes—all were irresistible.” Her Bill-isms ring true. In what must have been a riposte to Rosenberg’s action painting, de Kooning declared, “Life, the moment it is made into art, is only art.” Schloss remembers, as others have, how de Kooning’s Dutch accent turned words into other words—and created new meanings. His friends were confused when he boasted that he now had “a job teaching at jail!,” not immediately understanding that he was headed for the Yale School of Art. Schloss has a sweet sense of humor. “I danced the tango with Franz [Kline],” she writes of some party. “I danced the polka with Bill. The Action Painters were not the world’s greatest dancers, but there was nothing more fun than dancing with them.”

Among the men Schloss evokes with clear-eyed affection is Hess, who both as a writer and an editor at ARTnews did much to shape art criticism in the 1950s and 1960s. “Tom,” she remembers, “had a high oval forehead, a crew cut, a fleshy nose, sensual lips, and a bright, questioning look.” Rosenberg and Hess were good friends. I suspect that Rosenberg’s occasional efforts to embrace the sensuous qualities of paintings in his writing of the 1960s and 1970s owed something to Hess, who at ARTnews brought together a group of poet-critics and encouraged them to emphasize their immediate impression of a work of art. It was their writing that Greenberg dismissed—along with Rosenberg’s—as “pseudo-description,” “pseudo-poetry,” and “perversions and abortions of discourse” in “How Art Writing Earns Its Bad Name.” But what Greenberg regarded as fuzzy thinking reflected—at least at its best, often in the critical prose of Fairfield Porter and John Ashbery, another friend of Schloss’s—a conviction that artistic experience was idiosyncratic and intuitive, the celebration of an ineradicable inner necessity. Most of the critics Hess gathered around ARTnews felt no need to fit the artist into some grand scheme or interpret artistic independence as a criticism of the wider society, as was Rosenberg’s habit.

There was always something messianic about Rosenberg’s enterprise. Although he had worried about the popularization of the avant-garde in “The American Action Painters,” writing mockingly about “the expanding caste of professional enlighteners of the masses,” he embraced the much larger audience that he could reach at The New Yorker. I wouldn’t put it past him to have sometimes imagined that he was leading a revolution in taste among the democratic public that subscribed to the magazine. Balken has relatively little to say about Rosenberg’s work at the American Ad Council, a public service organization that over the years has promoted the American Red Cross, the Peace Corps, and other honorable efforts. Rosenberg worked there from 1946 to 1973; the job helped pay the bills in the decades before he found his way to the University of Chicago and The New Yorker. But I have a sneaking suspicion that he fit in pretty well. Wasn’t Rosenberg always, at heart, a kind of advertiser—an expert in a very lofty form of what we would now call branding? The phrases we associate with him—“the de-definition of art,” “the anxious object,” “art on the edge,” and the rest—are explosive rather than deep.

In Bellow’s “What Kind of Day Did You Have?” there’s a suggestion that the Rosenberg character is “nothing but a promoter.” That wasn’t Bellow’s view of his friend. He praised Rosenberg for taking up “the challenge of the new world, its cultural wildness.” But it was a view Bellow invited his readers to consider. As a writer and thinker Rosenberg dazzles but fails to ever quite come into focus. What is beyond question is that he stands out in the herd of independent minds he so gleefully examined. It takes one to know one.