Elizabeth I launched her defense against the Spanish Armada in 1588 with an unforgettable image: “I have the body of a weak, and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king.” Only a sovereign could transcend sexual difference, cloaking a king’s power in a woman’s flesh. But some saw this gender paradox as a kind of monstrosity. John Knox, the Scottish religious reformer and radical, had published The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women in 1558, the year of Elizabeth’s coronation. In it, he asked: How is it that the weak, the foolish, and the impotent may rule the strong? “Their sight in civil regiment is but blindness; their strength, weakness; their counsel, foolishness; and judgement, frenzy.” From his pulpit Knox preached that female rule was an abomination in the eyes of God.

In his time and our own, women’s power has given rise to propaganda, romance, intrigue, scandal, and myth. Think of Henry VIII’s six wives and their reputations as shrews, sexpots, and frumps; Mary Tudor, commonly known as Bloody Mary, burning Protestants and their unborn children alive at the stake; Mary, Queen of Scots, corrupting the throne with, as her Protestant opponents wrote, “her lewde lust and sensualitie”; Catherine de’ Medici, rumored to eat small children and assassinate her enemies using gloves scented with poison; or Marguerite de Valois, Catherine’s daughter, carrying around her dead lovers’ embalmed hearts in her pockets.

Historians have worked hard in recent decades to ground these women’s reputations in fact rather than sensationalism. Drawing on this research, Maureen Quilligan gives us a feminist history of early modern queenship in When Women Ruled the World. A specialist in English Renaissance literature, Quilligan has published widely on allegory and gender; her coedited volume Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe (1986) remains an important milestone in our understanding of gender and patriarchy in early modern European culture and society.

When Women Ruled the World focuses on four of the best known of Europe’s many Renaissance queens: Mary Tudor, Elizabeth Tudor, Mary Stuart, and Catherine de’ Medici. Many bewigged heads roll. But the book departs from the usual blood and gore of biographical accounts to emphasize instead the “shared nature” of these queens’ sovereign power, arguing that they were bound to one another not only by dynastic connections and political interest but by a feeling of sisterhood. “Like fellow soldiers in a sororal troop, they did try to protect and aid each other, keeping each other’s backs, as it were, asking each other to aid any one of them who might be in peril,” Quilligan writes, echoing recent and tremendously popular histories of queenship, most notably Sarah Gristwood’s Game of Queens (2016). Two of the queens Quilligan covers were actual sisters: Mary and Elizabeth Tudor were both daughters of Henry VIII, by successive wives. Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, was their cousin. At sixteen, Mary Stuart married Catherine de’ Medici’s son François de Valois, and she became queen of France a year later; Catherine remained interested in Mary’s affairs long after François died and she claimed the Scottish throne.

Quilligan argues that her account of a united group of women rulers is a feminist corrective to generations of scholarship that has privileged the queens’ enmities over their gestures of solidarity, and the grotesque over their political accomplishments. David Hume, for example, flattened the relationship between Elizabeth and Mary Stuart into one of “many little passions and narrow jealousies.” Jules Michelet called Catherine de’ Medici the “maggot that crawled out of Italy’s tomb.” Popular culture has been even crueler, playing up the trifling jealousies and petty hatreds of silly women with too much power and too much time on their hands. In Quilligan’s telling, however, the sisterhood of queens was not so much a monstrous regiment as a “prudente Gynecocratie”—the French poet Pierre de Ronsard’s term for Europe’s rule by female sovereigns.

The problem with this story of sisterhood is that the queens did, in fact, do some monstrous things to one another—none more so than Elizabeth, who ordered the execution of her “sister queen” and “twin sun,” Mary, Queen of Scots. After François died and Mary returned to Scotland, she wed Henry Darnley, an egomaniacal drunk who was blown up by rebels in 1567; she then possibly eloped with—but was more likely kidnapped and raped by—James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, a nobleman at her court. The following year, when Scottish nobles rebelled against the crown, Mary fled to England. Because, as a great-granddaughter of Henry VII, she had a legitimate claim to the English throne, Elizabeth kept her imprisoned for eighteen years in country houses in Derbyshire. In 1586, after Elizabeth was presented with forged evidence suggesting Mary’s complicity in Darnley’s assassination and participation in plots against Elizabeth’s rule, Mary’s agreeable incarceration had to end. She was brought to trial for treason and sentenced to death; Elizabeth signed her execution warrant. It took three swings of the axe to behead her.

Advertisement

An execution may seem incontrovertible evidence of Elizabeth’s enmity toward Mary. Certainly past generations of historians (and poets, playwrights, and film directors) have seen the execution as the culmination of long-held jealousies and resentments. Early in Mary’s reign, the Scottish ambassador visiting Elizabeth’s court recorded that she enviously asked him to describe Mary’s appearance, dancing abilities, and musical talents—a thorny test of his diplomatic skills. In 1566, when Mary gave birth to a son—the future James VI of Scotland and James I of England—Elizabeth is reported to have cried in despair, “The queen of Scots is this day lighter of a fair son, and I am but a barren stock!”

Quilligan asks us to reconsider. Soon after deploring her own barrenness, Elizabeth sent Mary a solid gold baptismal font encrusted with jewels—an exorbitant gift that makes it difficult to characterize the Virgin Queen as straightforwardly jealous of Mary’s marriage, fertility, and assured line of succession. Elizabeth gave James his baptismal name, too, and seemed to have thought of herself as a second mother to him, writing that he was “our child, born of our own body.” Quilligan places the blame for Mary’s execution chiefly with William Cecil, Elizabeth’s counselor, who contrived evidence of Mary’s plots against her reign and sent Mary’s death warrant to her prison cell before Elizabeth could reconsider. Elizabeth evidently regretted the execution, writing to James, “I would you knew though not felt the extreme dolor that overwhelms my mind for that miserable accident which far contrary to my meaning hath befallen.”

That “miserable accident” had grave implications, as Elizabeth knew well. Though Elizabeth signed the execution warrant, Mary Stuart had been tried openly for treason. A civil court had claimed new powers to pass judgment on a reigning queen. At the same time, Quilligan explains, the patriarchal Reformation posed its own threats to female rule—and, indeed, to the monarchy itself. John Knox’s criticism of the monstrous regiment of women expanded over time to become a radical rejection of the divine right of kings. For Knox, a legitimate king was not born but elected by his Protestant subjects, who were themselves moved by God—and so they could also “unelect” him, in Knox’s phrase. Elizabeth banned him from England for saying so and ordered a sermon to be delivered that preached that “Christ taught us plainly that even wicked rulers have their power and authority from God.” But with Mary’s execution, Knox’s radical dream that subjects could “unelect” a monarch came closer to reality.

Queens became newly subject to their subjects, the nature of sovereign power transformed. A sign appeared briefly near Mary Stuart’s tomb:

By one and the same wicked sentence is both Mary, Queen of Scots doomed to a natural death, and all surviving kings, being made as common people, are subject to a civil death. A new and unexampled kind of tomb is here extant, wherein the living are enclosed with the dead: for know, that with the sacred ashes of saint Mary here lieth violate and prostrate the majesty of all kings and princes.

Sixty-two years later Parliament voted to execute Mary Stuart’s grandson King Charles I. What had begun as a critique of female rule had become a real and future tomb for sovereignty itself.

When Women Ruled the World departs from traditional political narratives of the queens’ tangled reigns to pay special attention to the gifts they exchanged. Drawing on feminist anthropology, Quilligan argues that royal gifts concentrated wealth, power, and prestige privately within dynastic families, and helped women claim political authority in a patriarchal world. She suggests that patterns of female gift-giving stand in stark contrast to gift-giving by men: men’s gifts forced the reciprocal return of another gift, were given in public, and often took the form of an exchange of women. Gifts thus help to illuminate the bonds between givers and recipients that, Quilligan claims, previously escaped historians’ notice. For example, at the age of eleven Elizabeth Tudor made a beautiful book for her stepmother, Katherine Parr: she translated Marguerite de Navarre’s poetry into English, copied out the text in her own hand, and embroidered a cover on which she showcased Katherine’s initials. Elizabeth’s gift, Quilligan suggests, helped her rejoin the Tudor dynasty after the tumult of her mother’s death and her father’s remarriage.

Advertisement

Textiles carried special significance for female rulers. Mary Stuart gave Elizabeth a red silk petticoat that she embroidered herself with silver thread; the French ambassador observed that Elizabeth seemed “much softened” toward Mary after receiving it. Catherine de’ Medici commissioned a monumental tapestry cycle and gave it to her granddaughter Christina of Lorraine, who, when she became Grand Duchess of Tuscany, carried them back to the Medici ancestral home in Florence along with the rest of her dowry, which included rock crystal, pearl-studded bed hangings, and 50,000 scudi (estimated to be $1 million in today’s money). Quilligan writes that Christina’s opulent gifts “would have demonstrated, as her grandmother would have wished them to do, her wealth, lineage, and royal dynastic connections.”

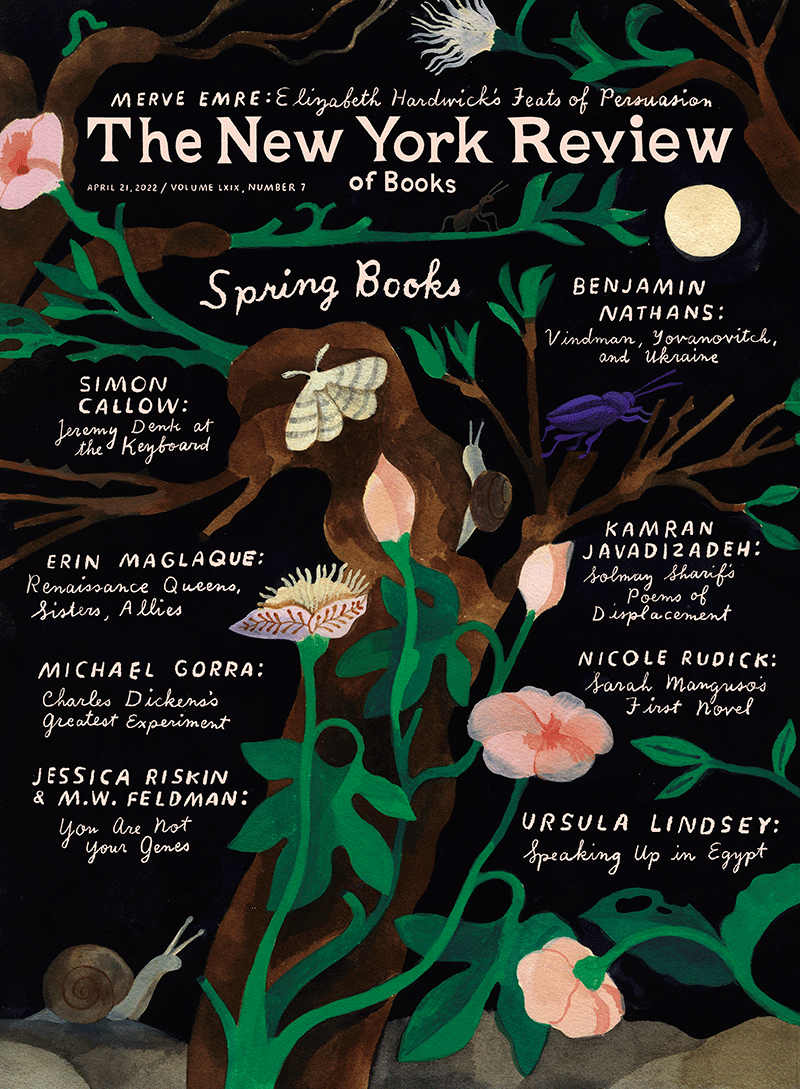

An exceptionally beautiful pear-shaped pearl, known as La Peregrina, “makes visible the inheritance of blood…through the ages.” Found by an enslaved African working in a Panamanian fishery, it entered Philip II’s collection in the 1560s. In a portrait painted in 1605, Philip’s daughter-in-law, Margaret of Austria, delicately strokes the gem with slender fingers. The pearl was beloved by generations of Habsburg royal women until Napoleon conquered Spain in 1808 and took La Peregrina with him when he left. (It was eventually sold to an English family, from whom Richard Burton bought it for Elizabeth Taylor in 1969. La Peregrina went missing once in their suite in Caesars Palace in Las Vegas; Liz was quite upset until she discovered it in her dog’s mouth.) Elizabeth I liked the look of La Peregrina but didn’t want to have to marry Philip II to get it, so she bought her own nearly identical drop pearl, shown in the Armada portrait of 1588 (see illustration on page 25). Lest anyone forget that she was a virgin, the pearl dangles from a gaudy pink bow tightly knotted over her crotch.

For a contemporary parallel, Quilligan asks us to think of Kate Middleton, who wears Diana Spencer’s ring, or of Meghan Markle, who wears a ring set with two of Diana’s diamonds. Gifts of pearls and diamonds illustrate “how deeply we seem to know that female agency is inherited from generations of forebears.” Maybe it’s vulgar to think instead of Princess Michael of Kent, lips pursed in the front seat of an SUV on the way to lunch with Markle, a glittering seventeenth-century blackamoor brooch pinned to her breast. Royal women know the communicative power of jewels—and that bloodlines of rule and bloodlines of race are kindred. While jewels can create dynastic webs of sisterhood, they can also be used to mutilate them.

The centerpiece of Quilligan’s object histories is the so-called prison embroideries made by Mary, Queen of Scots. While trapped in the Shrewsbury estates, far from Scotland and far from the sea, Mary designed and sewed elaborate tapestry panels with her companion, Bess of Hardwick. After seeing Mary and asking how she passed the time, Elizabeth’s envoy reported, “She said that all the day she wrought with her needle, and that the diversity of the colours made the work seem less tedious, and continued so long at it till very pain did make her to give over.” The result was more than a hundred tapestry panels that reworked illustrations from natural history books, scenes from classical literature, and motifs from emblem books in expertly plied needle and thread.

This was not just the busywork of a bored prisoner. Historians have long seen Mary’s embroideries as a particularly female form of defiance, reminiscent of Ovid’s account of Philomela, who weaves a tapestry to tell of her rape by Tereus, after he cut out her tongue. In one tapestry panel, an orange tabby cat wearing a crown bats at a gray mouse. Elizabeth, of course, was a famed redhead; when Mary was executed, the axeman held her head aloft before the crowd, only for the head to slip out of her wig and tumble, revealing her gray hair. Another panel shows a phoenix rising from its ashes, framed by Mary’s initials, a representation of her motto “In my end is my beginning.” In the Noble Women of the Ancient World series that Mary made with Bess, Mary is depicted as the figure of Chastity, flanked by a unicorn—a visual claim for her purity, contrary to her scandalous reputation. Not only were the tapestries a distraction from her imprisonment, Quilligan writes, but they were “inalienable objects of political resistance.”

But are the embroideries so transparent a window onto Mary’s intentions? Mary and Bess created the panels in collaboration with male and female household servants, with visiting aristocratic daughters and granddaughters, and with the professional male embroiderers who joined the household to complete special silk appliqué work. Similarly, the gorgeous tapestries that Catherine de’ Medici “almost certainly” commissioned weren’t made by her hand or in her household, but in professional workshops in the Low Countries. Quilligan suggests that Catherine intended the Valois tapestries to be redemptive, to project an image of tolerance and peace after the catastrophe of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in France in 1572; they showed the Catholic de Guise family and the Huguenot Bourbon families peacefully reconciled. But the Protestant weavers in the north erased Charles IX from the design, in an act of artistic retribution for his role in the massacre. The textiles are not unmediated expressions of the queens’ intentions, then, but objects wrought collectively and cooperatively by men and women across social classes and confessional identities—and are all the more fascinating for it. And yet these complexities are relegated to the footnotes of Quilligan’s story.

Quilligan wants us to reconsider these queens not only as affectionate allies but as uniquely able to bring peace to Europe. Elizabeth and Catherine de’ Medici, for example, settled the Treaty of Troyes in 1564, achieving a lasting peace between England and France that had eluded previous generations of kings. The French poet Ronsard commemorated the treaty:

For truly, that which the kings of France and England…did not know how to do, two queens…not only undertook but perfected: showing by such a magnanimous act, how the female sex, previously denied rule, is by its generous nature completely worthy of command.

But were these queens uniquely tolerant rulers during a uniquely violent century? Proving this is a steeper task. Bloody Mary burned nearly three hundred Protestants, including two infants, at the stake during her reign. Catherine de’ Medici also poses a problem. Once thought to have masterminded the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre—a monthlong spectacle of death in which thousands of Protestants were murdered by their Catholic neighbors—Catherine has been remembered as the wicked Reine Mère. Quilligan follows the more moderate modern consensus that Catherine did not strategize the mass murder of French Protestants, even though she did plot the bungled assassination that helped to ignite the fuse of Saint Bartholomew’s Day. Particularly in the midst of religious schism, early modern queenship required the use of violence.

And even if women were inclined toward peace, was this some inherent virtue of their sex, or a result of contemporary gendered expectations of royal rule? These questions are left unanswered. Certainly the queens wanted to be perceived as peaceful; Elizabeth worked diligently to portray her feminine desire for peace. In her conclusion, Quilligan celebrates Elizabeth, writing that she won the loyalty of her subjects by her “constancy…by her bravery, her intelligence, and frankly, by the beautiful delivery, the wit, the Good Queen Bess simplicity and honesty and soaring style of her speeches.” It’s true that she knew how to give an excellent speech. The same Good Queen Bess also ordered seven hundred commoners killed in the north after a rebellion in 1569 by Catholic aristocrats, the earls of Westmorland and Northumberland, even though the earls had received no popular support.

Queens like Elizabeth are revered figures of feminist history and popular culture because they possessed power, a rare feminine asset. But power has its own history. The agency beloved of twenty-first-century liberal feminism is not the same as sixteenth-century sovereignty. Invested in a ruler through an accident of birth, sovereignty was maintained as much through state-authorized violence as through consent. Quilligan is at pains to explain away the violence: Elizabeth’s execution of Mary, for instance, was the lamentable consequence of the power struggles of men. The queens believed in religious toleration, except when they didn’t, and then it was the male figures of the patriarchal Reformation who were responsible for upsetting the queens’ peaceful instincts. And yet we cannot explain away the killing, because it was fundamental to the meaning of sovereignty in early modern times—even when women signed the warrants.

In a laudable effort to address generations of misogynistic writing about these queens, Quilligan has emphasized their virtues: their sisterhood, peaceful reigns, and artistic abilities. In her telling, the women who ruled the world were highly educated; hyperliterate; skilled horsewomen, dancers, and musicians; inspirational speakers; deft politicians. They were at times warm friends and affectionate sisters. They were independent and defiant. They were frequently tolerant. But when we refashion queens as proto-feminists—a kind of sorority of early modern girlbosses—we lose sight of the complexities, and indeed the atrocities, involved in being a sovereign. This is not to deny their accomplishments as politicians, patrons, or artists. But without a consideration of the violence that secured their power, we are left with squeaky-clean stories of brave and good and virtuous queens—the queens of fairy tale, not history.