A coastal hotel in Bordeaux, a Marrakesh bathhouse, the first pet cemetery in the US, a floating bar in Paris renowned for its weekly Soirées Gay: as the most famous female artist of the nineteenth century, Rosa Bonheur left her name across France and beyond.1 For many people now, it may be only a name, since the decline of Bonheur’s fame after her death in 1899 was as precipitous as her rise through the Paris art world had been. Born in 1822 into a poor family in Bordeaux, Bonheur by her mid-twenties had become a celebrated animalière, or painter (and sculptor) of animals: she painted oxen in the field, lions, horses, sheep (wild and domestic), and countless cows. Her best-known picture, The Horse Fair (1852–1855), hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was donated by Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had purchased it in 1887 for $53,000 (about $1.6 million today).

Bonheur’s painstaking realism has long since fallen out of fashion, but interest in her life as well as her art is on the rise. This fall the Musée d’Orsay will host its first exhibition devoted to her work; a French postage stamp honoring her bicentennial was issued in March; and recently, the first full-scale biography in forty years appeared: Art Is a Tyrant by Catherine Hewitt.

Bonheur described her life as one of “struggle, triumph, and glory.” At the height of her career she had a studio in Paris, a mansion in Nice, and a château at the edge of the Fontainebleau forest—now a museum—where she kept an unruly menagerie that included monkeys, wild horses from America (a gift from an admirer), and a free-roaming lion named Fathma. On one trip to England and Scotland, she acquired a bull, two cows, four sheep, and three calves. “They are so picturesque and their color so beautiful that I should like to paint them all at the same time,” she wrote to her sister, Juliette. “I shouldn’t like to fail with a single one.” Hewitt writes that she studied animals’ eyes especially; in them she “felt certain she could see an animal’s soul.”

Animalier art developed out of the Romantic movement and flourished in France and England from the 1830s through the end of the nineteenth century. The Romantics had a complicated relationship with nature, both thrilling to its terrifying power and intensity and seeking to reconnect with its peaceful, uncorrupted beauties. The art historian Whitney Chadwick has argued that “it was the search for expressions of feeling unencumbered by social constraints that underlay both the embrace of animal imagery…and the fame enjoyed by Rosa Bonheur.”

Leading animaliers during Bonheur’s youth included Pierre Jules Mêne, Jacques Raymond Brascassat, and Constant Troyon; she admired and learned from them. (She was rarely adversarial, even as she clambered up the ranks.) The Académie des Beaux-Arts showed some resistance at first to what seemed a trivial genre, but after King Louis-Philippe awarded several public commissions to the sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye, his success helped establish animal art within the complicated hierarchies of the French academic canon—a middling position somewhere between landscape and genre painting, Théophile Gautier argued. Barye specialized in depictions of exotic beasts attacking or consuming their prey, with titles like Python Killing a Gnu and Tiger Devouring a Gavial. The first paintings Bonheur submitted to the Paris Salon showed such a mastery of anatomy and naturalistic detail that her work was compared with his.

Though Bonheur, a generation younger, became far more successful, Barye’s sinuous, expressive forms weathered the transition to modernism better than hers. (A line of influence can be drawn between Barye, his student Rodin, and Brancusi, who briefly apprenticed with Rodin.) She is perhaps more closely allied with the English painter and sculptor Sir Edwin Landseer, whom she revered. Hewitt describes Bonheur’s 1855 visit to Landseer’s studio in London, as recollected by her chaperone, Lady Eastlake, who translated Landseer’s remarks for the silent Bonheur:

Landseer presented one picture or sketch after another, and at the end of the visit, offered her two of his brother’s engravings of his Night (c. 1853) and Morning (c. 1853), on which he inscribed her name with his.

Afterward, in the carriage home, “the Englishwoman noticed that ‘the little head was turned from me, her face streaming with tears.’”

Marie-Rosalie Bonheur was the eldest of four siblings who all became professional artists. Her father, Raimond, was a minor genre painter and drawing instructor, which became Rosa’s entrée to a profession largely closed to women. From a young age she was artistically precocious but indifferent to schooling; she had no interest in learning to read until her mother, Sophie, taught her the alphabet by having her draw animals for each letter.

Perennially short of cash, Raimond moved the family to Paris when Rosa was seven, beginning a difficult, itinerant existence. Prone to enthusiasms, he converted to Saint-Simonianism, a burgeoning Christian socialist movement that advocated education for women, among other progressive ideals. In Paris, Rosa briefly attended her brothers’ school, and later wrote that this experiment in coeducation “emancipated me before I knew what emancipation meant and left me free to develop naturally and untrammelled.”

Advertisement

After Sophie’s early death—from strain and overwork, by most accounts—Raimond enrolled Rosa in a girls’ boarding school, where she made herself “an element of discord,” she recalled proudly. Only for art contests—judged by her father—did she apply herself. Thus, almost as a last resort, she won the chance to pursue a career as an artist. Raimond organized a home académie for her, assigning her copying tasks similar to those at the all-male École des Beaux-Arts. Soon she was painting from nature and going to the Louvre to copy masterworks and endure the jibes of male art students. Later, when Raimond suggested she sign her work with his name, she refused.

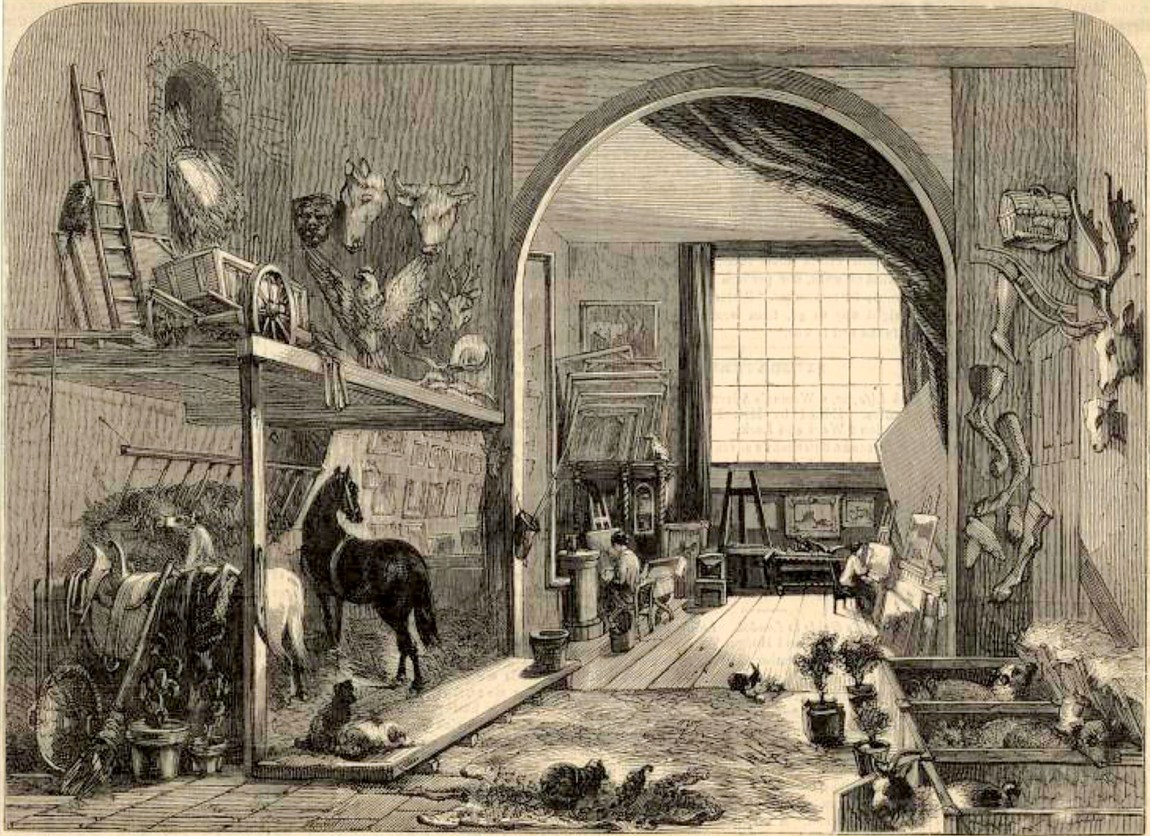

As well as sketching in the Bois de Boulogne and at the zoo in the Jardin des Plantes, Bonheur also ventured into Paris slaughterhouses, like her male contemporaries; these studies gave her the command of anatomy that caught the eye of the Salon judges. She also made trips into the countryside to sketch animals in nature: “I loved capturing the rapid movement of the animals, the sheen of their coats, the subtlety of their characters, for each animal has its own physiognomy.” At home she kept a growing menagerie of models, including birds, rabbits, ducks, butterflies, rats, a squirrel named Kiki, a ewe, and a billy goat. Guests were “greeted by the unmistakable odor of livestock and the sounds of bleating, chirruping and scuttling of all sorts.” Upstairs, in a large, well-lit room, the Bonheur siblings set up their easels beside their father’s—a cottage industry in the making.

Bonheur made her debut at the 1841 Paris Salon at nineteen; the jury selected two of her works: a sketch of goats and sheep grazing and a painting of rabbits. Although women had been exhibiting at the Salon since the 1780s—Raimond had urged Rosa to adopt Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun as a role model—their work was seldom taken seriously. “Women painters prefer sentimental little scenes, flowers and portraits,” wrote Théophile Thoré, a prominent critic of the day. But Bonheur pressed forward with her unusual specialty: three paintings and a clay sculpture in 1842, two paintings and a plaster bull in 1843. Every work she submitted to the Salon was accepted. She began to attract sales and in 1844 received her first brief press mention: the models for her painting Sheep in a Meadow were said to be among “‘the softest, cleanest, most abundant in fleecy wool’ of their species,” Hewitt writes.

Her reputation grew with each Salon. She earned a third-class prize in 1845 and finally, three years later, a gold medal—awarded by a jury that included Camille Corot, Ernest Meissonier, and Eugène Delacroix. Government commissions followed. The first was Plowing in the Nivernais (1849): on a canvas of nearly 52 by 100 inches, the muscularity of Bonheur’s oxen, straining against the harness in a freshly plowed field glowing with sunlight—a genre one might dub the Bucolic Heroic—compares well with the tepid cattle paintings of Gustave Courbet from the same period. The painting, now at the Musée d’Orsay, was a crowd favorite at the Salon. “It is horribly like the real thing,” Cézanne later remarked.

The peak of Bonheur’s career, though, was without a doubt her monumental painting The Horse Fair. At 96 by 199 inches, it covers most of a wall in the Met’s European wing. Bonheur had begun preliminary sketches for two paintings, The Horse Fair and Haymaking in the Auvergne, when a French government minister, offered the choice, commissioned the latter scene. It would prove a poor bargain for the nation, since Haymaking, now at the Château de Fontainebleau, feels static and forced, with generic peasants and a heavy central wedge of shadow cast by the hay cart. In contrast, The Horse Fair is a masterpiece of animal energy, its galloping, barely controlled horses spinning against the trees on a wide, dusty Parisian boulevard, and even the sky alive with motion.

The idea for the painting had come to Bonheur while sketching in the Pyrenees; she wanted to work on a large scale and remembered the fragment of the Parthenon frieze she had studied in the Louvre. For months, discreetly clad in trousers, she frequented the twice-weekly horse market on the Boulevard de l’Hôpital, sketching the Percheron workhorses and the men who handled them. She prioritized her “great picture” over Haymaking, and had to work relentlessly to complete it before the 1853 Salon. If it failed, the government might withdraw its commission.

Advertisement

Hewitt recounts the sensation The Horse Fair created. Bonheur deserved a first-class medal, Delacroix remarked in his journal, but no artist could be awarded the same prize twice. A London-based art dealer, Ernest Gambart, bought the painting and arranged for it to tour Britain, including a private viewing for Queen Victoria. Thousands of reproductions followed. On her 1856 trip to England and Scotland with Gambart, she was surrounded by admirers, and even John Ruskin came to meet her, though he thought her preference for animals an artistic weakness. During an after-dinner argument, he exclaimed, “I don’t yield; to vanquish me, you would have to crush me.” “I wouldn’t like to go so far as that,” Bonheur replied.

The first biography of Bonheur appeared in 1856, and in 1865 she was made a chevalier of the Légion d’honneur. When Empress Eugénie, the wife of Napoleon III, pinned the medal on Bonheur’s chest, she said, “Genius has no sex.”

In his essay “Why Look at Animals?” (1977), John Berger noted the fundamental nostalgia of animalier art:

The treatment of animals in nineteenth-century romantic painting was already an acknowledgement of their impending disappearance. The images are of animals receding into a wildness that existed only in the imagination.

Publicity materials for the upcoming Musée d’Orsay exhibition suggest that the curators aim to investigate how Bonheur’s portrayal of animals “calls into question the hierarchy between species.” That may be going too far, but her art both influenced and developed alongside the emerging animal welfare movement. The first animal protection laws in France appeared in the 1850s, and Bonheur corresponded with friends in England’s antivivisection movement.

On the other hand, as Hewitt points out, Bonheur was no vegetarian; her letters are full of delighted descriptions of country pâté and haunches of venison. She loved hunting, and a picture survives of her sketching a freshly killed deer strung up in a lifelike standing pose—a literal nature morte that now feels grotesque and at odds with her genuine sympathy for animals. (A friend of Bonheur’s recalled a little mare at Fontainebleau that would rear up to rest its hooves on her shoulders and take a sugar cube from her mouth, then follow her inside.)

As soon as she could afford it, Bonheur left Paris to live at Fontainebleau, where she could quietly cohabit with her partner, Nathalie Micas, who was also her studio assistant and business manager. (When Gambart made an offer on The Horse Fair, Hewitt tells us, it was Micas who drove a hard bargain.) At Fontainebleau Bonheur painted as much as eighteen hours a day and walked for miles in all weather through the woods in her favorite costume of loose peasant trousers. When Bonheur is written about—then as now—invariably the trousers feature. Cross-dressing was illegal in France at the time: an 1800 statute had sharply restricted women’s rights, including what they were allowed to wear, but Bonheur received a rare permission de travestissement—official permission to cross-dress.2 It was granted on hygienic grounds, so that she would not have to sully her skirts with mud or manure as she worked.

Bonheur had first adopted trousers to avoid harassment from men she encountered while out sketching. “Her strong face and short hair lent themselves admirably to this disguise,” one relative recalled. “Rosa was everywhere taken for a young man.” The garments proved congenial, and she soon wore them routinely at home. In the woods or when traveling, she added a revolver.

Bonheur’s retreat to Fontainebleau cost her some currency in the Paris art scene. She stopped exhibiting in the Salons, in part because Gambart and her Paris dealer, Tedesco, snapped up most of her new work for foreign buyers. In France, while the honors piled up and fashionable people interrupted her studio hours, she became a respected elder rather than a living influence on younger artists.

After Bonheur’s death in 1899, demand for her work fell as modernism took hold. By World War I, her paintings, along with the entire animalier genre, seemed hopelessly passé. She was excluded from the standard art history texts, beginning with Helen Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, first published in 1926.3 Though included in Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1979), she didn’t merit a place setting of her own. The critic Robert Hughes referred to her as “the French cattle painter Rosa Bonheur” and pointed to her career as an example of inflated valuations that bottomed out.

In her 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Linda Nochlin observed that successful artists like Bonheur were often cited to justify limited opportunities for women: if she could reach such heights almost unaided, women clearly weren’t hindered by their exclusion from the best art schools and high-profile awards like the Prix de Rome. Bonheur’s challenge to gender stereotypes was nevertheless the main lens through which contemporaries saw her. While Gautier declared her “at the very top of the field of animal painting,” most critics lauded her in the usual terms accorded gifted women: “Mlle Bonheur paints almost like a man” (Thoré again). Sadly, Hewitt uncritically reiterates what became a standard dichotomy between Rosa’s “masculine” manner and ambition and her “feminine” technique. “She looked and behaved like a boy but when she drew, she did so with feminine sensitivity,” she writes; Bonheur “possessed the stamina of a man and the delicacy of touch of a woman.”

More surprising is that Bonheur’s gender presentation sparked so little objection during her lifetime. (She was once arrested because police assumed she was a cross-dressing man.) To some extent, her trousers may have made sense to critics for whom genius did have a sex. As Germaine Greer wrote, “It was thought that Bonheur had eschewed her sexuality altogether and become great as a result.”

In some respects, Bonheur followed one of her literary heroes, George Sand, who wore trousers to get into men’s clubs and other places closed to her as a woman. But Bonheur shunned the kind of notoriety Sand courted. “If you see me dressed this way, it is not in the least to make myself stand out, as too many women have done,” she remarked late in life, “but only for my work.” Yet it was not only for her work: she habitually wore trousers at home, and her biographers made much of the dresses she changed into for visits or travel; Bonheur loved to recount her frantic struggles into a dress when Empress Eugénie took to dropping by unannounced. A neighbor recalled that “what bored her most was going to Paris, for it meant the discarding of trousers, smock, and felt hat, as well as the putting away of cigarettes.”

Hewitt does not touch on one relevant midcentury cultural development described by Henry James and others: the circle of prominent American women artists in Rome, several of whom (including Harriet Hosmer, Emma Stebbins, and Mary Edmonia Lewis) formed intimate partnerships with women; some, like Hosmer, also wore “mannish” clothes. Bonheur had met Hosmer, eight years her junior, and avidly followed her success.4 She was also connected to this circle through the Welsh sculptor Mary Lloyd, Bonheur’s friend and former student, and the partner of the British feminist Frances Power Cobbe. The kind of mutually supportive, woman-centered idyll that Bonheur created with Micas may have been a model for other ambitious women.

Art Is a Tyrant offers an orderly account of Bonheur’s life and career despite the chaotic abundance of her two main sources, both American: Theodore Stanton’s Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur (1910) and Anna Klumpke’s Rosa Bonheur: Sa vie, son oeuvre (1908). Along with recalling his own conversations with Bonheur, Stanton (the son of Elizabeth Cady Stanton) collected hundreds of letters and reminiscences of the artist, producing a 413-page, closely printed cornucopia. Bonheur regarded his questions as an opportunity to set the record straight and rattled on engagingly.

Similarly, when Anna Klumpke, an American artist and Bonheur’s companion in the last year of her life, shared her journal with Bonheur—an almost worshipful record of their days together—she again took the chance to correct earlier versions of her story, all written by men. “The authors did not know how to plumb the depths of her mind,” Klumpke remarked, but “this instinctive reserve vanished when she faced a woman whose love and devotion to her were sure.” The resulting volume, translated by Gretchen van Slyke as Rosa Bonheur: The Artist’s (Auto)biography (1997), is a syrupy but moving intergenerational love story, as well as a fascinating “as told to” autobiography of Bonheur from the perspective of old age.

To these rich primary materials Hewitt deftly adds political and cultural background, weaving Bonheur’s vivid recollections into fuller accounts of, for example, the unrest of the 1830s (the Paris of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables) and the revolution in 1848, art market changes that saw the decline of the government-controlled Salon system, and the rise of the independent art dealer, which brought Bonheur financial success. At her death, in addition to the château, she left Klumpke almost her entire estate: investments totaling over 300,000 francs and thousands of artworks worth over a million francs.

The stories Bonheur told Klumpke—along with her somewhat combative last will and testament—make it clear that, despite all she had achieved, she still felt embattled: if she failed to protect her hard-won wealth, the forces of patriarchy (in the form of her greedy nephews) would rush in. “My family has always taken a dim view of my right to live as I please,” she wrote in a testamentary letter, justifying her decision to leave most of her estate to Klumpke. “Having done my duty by my family, I was entitled, like any adult earning her own living, to my independence.”

Several photos survive of Bonheur with Micas, who was described by a friend as “odd, original, and devoted.” Hewitt includes the best of these, taken in Bonheur’s studio in their late middle age. Micas slumps unsmiling in an armchair, with a little dog curled on her lap; Bonheur stands behind her in a painting smock. Both eye the camera with some skepticism. Micas dedicated her life to Bonheur, had a secret bedroom near hers in the château, and died in her arms in 1889. Bonheur’s protracted grief lasted until Klumpke, a successful portraitist in her early forties who had idolized Bonheur from childhood, came to the château to paint her portrait in 1898. Soon Bonheur was writing to her, “I thought I’d buried love with my poor Nathalie; but my old heart has come back alive to the love I see in your eyes.” Negotiations with the Klumpke family to gain their permission for her to move in with Bonheur read very much like marriage settlement agreements.

Only months later, Bonheur died in Micas’s bed with Klumpke’s arms around her. As promised, Klumpke preserved the château, which was handed down through generations of her family until its purchase by the present owner.

“She used to make her own little cigarettes,” a friend recalled of Bonheur.

When conversing in her studio, she would often be engaged all the time rolling them. Even when she was as old as seventy-five, I have seen her sitting up on the side of her table…just like a young man, with a smoking cigarette in her hand. Her pretty little foot would then slip conspicuously out from under her trousers.

Another friend recalled that when Bonheur walked through the fields, “the peasants returning from their day’s labour would bow to this ‘little man with his fine white locks.’”

Bonheur is buried in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, with Micas and Klumpke, who died in 1942. Shortly before her death, Klumpke bequeathed one of Bonheur’s “feminine outfits” to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco: a black velvet and satin ensemble of jacket, vest, and skirt, with sturdy black petticoat; the Légion d’honneur rosette was pinned to the front placket. Not one pair of the famous trousers appears to survive.

-

1

In 1979, Rosa Bonheur Memorial Park near Baltimore (since closed) also became the first cemetery to allow people to be buried alongside their pets. ↩

-

2

Incredibly, the cross-dressing law remained on the books, if largely ignored, until 2013. ↩

-

3

Granted, Bonheur was in a large, boisterous company of the forgotten: not a single woman made it into Art Through the Ages or the later standard textbook, H.W. Janson’s History of Art (1962). Gardner’s 1936 edition briefly mentioned Mary Cassatt and Georgia O’Keeffe, but Bonheur only finally made it into the seventh edition, published in 1976. She was excluded from Janson’s until the eighth edition in 1987—like all other women artists. ↩

-

4

Hosmer’s marble sculpture Zenobia in Chains (1859), now at the Huntington Gallery in California, was a triumph at the 1862 Great London Exhibition—and a shock to critics, who believed women could not sculpt stone; some at first argued that Zenobia must have been made by a man. ↩