The air was thick and humid, delivered on a warm breeze that belonged to June, on the November morning I brought one of my daughters to a ski swap in our corner of northwest Vermont. We found her some used gear for the season ahead and, for me, a dose of dread: temperatures climbed into the seventies, breaking records across the state. But all around me the mood was upbeat among the hundreds of skiers in T-shirts and flip-flops browsing racks of boots. Vermont winters can be grindingly long. Why not enjoy the reprieve?

Despite our state’s wintry associations, plenty of Vermonters fantasize about fleeing as they reach for their vitamin D supplements and windshield scrapers. Enduring the season is both “a privilege and a punishment,” wrote Charles Edward Crane in his 1941 book Winter in Vermont. “I doubt that half the world’s population knows what real winter is…. Those familiar with it must own to a familiarity that breeds contempt.” That contempt prevails across America’s higher latitudes, fueling real estate booms from Phoenix to Ft. Lauderdale. It’s why the verb “to winter” has taken on connotations of escape. If winter failed to arrive one of these years, one wonders how many of us would really miss it.

We’re now finding out, thanks to the 1.5 trillion tons of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution. A week after our sweltering day of ski shopping, the research group Climate Central released an analysis of temperature data from 238 locations across the United States between 1970 and 2022. “Winter is warming everywhere,” the study’s authors concluded, but cold places are warming faster than hot ones. Burlington has experienced the nation’s largest increase of average winter temperature since 1970: 7.1 degrees Fahrenheit. The number of warmer-than-normal winter days is increasing from year to year, cold snaps are shorter, and cold days just aren’t as cold anymore. What’s more, winter is losing ground at both ends: first frost arrives a month later than it did a century ago, and spring comes weeks sooner. These changes are closely linked to the rapid transformation of the Arctic, which is warming four times as fast as the rest of the world.

Some Europeans believed that cold originated from an island called Thule in the far north. Modern science has found some truth to the myth. Every December polar scientists issue updates on the quickening melt of Greenland’s ice sheet and the steady shrinking of seasonal sea ice. Arctic warming is disrupting the Gulf Stream current that keeps Northern Europe’s weather relatively mild for its latitude. It is also weakening the jet stream, which is more stable when there’s a large temperature difference between the polar region and midlatitudes. Without a firm jet stream serving as a barrier, the “polar vortex” of frigid air that swirls around the top of the world can leak south and linger for days or weeks.

As the Arctic keeps getting warmer, we can expect more such extremes: the climate will behave like a ship without ballast, tipping wildly from side to side. We will still get heavy snows and deep freezes, but thaws and rains will be nipping at their heels. In mid-December a foot of snow fell in Vermont’s mountains. A week later a bomb cyclone lashed our house with seventy-mile-per-hour gusts and hours of rain, shrinking the snowpack into a sheet of ice and then dropping a desultory sprinkling of powder on top. The same storm paralyzed Buffalo with four feet of drifting snow and pulled subfreezing Arctic air all the way down to Louisiana. By New Year’s Eve temperatures in Vermont reached back into the upper fifties; Montpelier, the capital, topped sixty. Steady rains turned roads to mud. The maple sap started running. My daughter’s first Nordic ski lesson was canceled: not enough snow.

This whiplash is winter’s new look. From late December into January, a series of nine atmospheric rivers—infused with moisture from a warming Pacific Ocean—brought record-setting precipitation to California, flooding parts of the Central Valley and piling snow up to the eaves of homes across the Sierra Nevada, blanketing resorts from Mammoth Mountain to Lake Tahoe. While the Sierras had their second-snowiest winter on record, a heat wave gave Europe its second warmest. On New Year’s Eve Munich hit sixty-eight degrees, as did a Swiss ski resort on January 1, a few days before it hosted a World Cup race. Slopes throughout the Alps were closed. Skiers were consigned to making laps on cartoonishly narrow strips of snow. Some resorts hauled in snow via trucks and helicopters, while others opened biking trails instead.

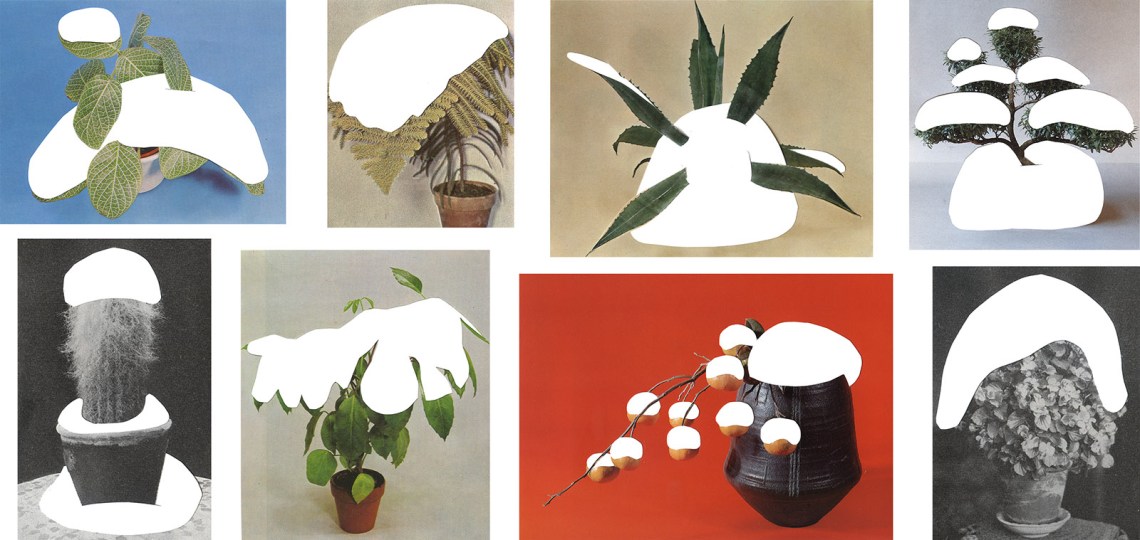

The heat wave offered a preview of what will almost surely happen later this century: a lack of snow and rising temperatures will force many, if not most, Alpine resorts to close. “Children born today will never see winters like we did,” the curator of the Swiss Alpine Museum in Bern tells Porter Fox in The Last Winter, as he leads the author through an exhibition designed to show future generations what the region’s winter sports scene was once like. “Winter is getting more and more like an abstract concept, like a fantasy world portrayed on television and in magazine ads.”

Advertisement

Winter has been the stuff of fantasy for a while now, a picturesque backdrop for the consumption of carefully curated experiences. Every November, right on cue, newspapers run articles with tips for finding beach vacation packages, ski lift ticket deals, or lifestyle hacks for hygge, the Scandinavian-inspired craze for getting cozy by candlelight with big sweaters. We mostly live as if winter’s constraints do not apply.

For much of human history, though, winter in the higher latitudes and elevations was a time of privation and narrow margins for error. “All things that lived and sprang by the benefit of Summer, fade and die by the hard cruelness of Winter,” observed one thirteenth-century Englishman. Staying alive, let alone comfortable, demanded a mix of ingenuity and sheer endurance. The kitchen or living room was typically the only heated room in the house, and bedrooms were nearly as cold as the outdoors. People stuffed straw around windows and covered them with paper. Solstice and other end-of-year celebrations were psychic prophylactics against the long months of darkness and isolation ahead. It’s no wonder that across cultures winter has long been personified as a mischievous, indifferent, or outright hostile force: Old Man Winter, Jack Frost, the fierce Norse goddess Skadi, or the ancient Greeks’ Boreas (“the Devouring One”), prone to outbursts of anger, who brought the season on the north wind.

With the advent of modern heating systems, global supply chains, and high-performance clothing in the twentieth century, winter became enjoyable from a safe remove, like a Siberian tiger pacing behind a zoo’s plexiglass barrier. In postwar Europe and North America, ski resorts proliferated and became winter playgrounds for the fast-growing middle classes. Thanks to the invention of the chairlift, the sport surged in popularity.

Skiing was both exhilarating in itself—a new way to actually enjoy being outdoors in winter—and a novel form of conspicuous consumption, equal parts grit and glamour. Fox is a child of this world. His grandfather was an “avid skier,” his mother worked at ski resorts in Austria in the 1960s, and his parents moved the family to northern Maine when he was three. “Week by week, we learned how to exist in our new, winterized world,” he writes, “and in the heart of winter, when it got dark at three in the afternoon, we learned to ski.” Skiing became a lifelong obsession.

I followed a parallel arc. As a kid, Fox clipped articles from ski magazines; I amassed a collection of resort maps, charting all the places where I would one day make turns. Fox chose to attend a college with its own ski area; so did I. A few years after graduating, he quit his job to ski in the Himalayas. I pulled that same maneuver in 2003. Powder magazine offered Fox a ski bum’s dream: to “spend three months of the winter finding the most exotic snowfields in the world.” He wrote and edited features for more than a decade, chronicling the endless pursuit of what its subscribers call “the stoke”—the euphoria of playing in the mountains.

I might have followed suit, if not for a season spent working at a resort in Colorado. The restaurant servers and lift operators measured out their winters in ski days and surfed away each summer in Baja before returning to the Rockies each fall. This lifestyle left me not so much envious as wary. At night my coworkers would watch Warren Miller ski movies like Endless Winter, but the experience put me more in mind of Groundhog Day. A small epiphany later came while I worked on a farm in a Himalayan village. Foreign tourists sometimes hiked through, passing the barley and alfalfa fields where the villagers labored, bent under loads of dried dung and fodder. My host family would occasionally exchange an obscure word to describe those Gore-Tex-clad trekkers: Skoryangspa! When I learned its meaning, I could only laugh at how perfectly the word skewered me and my fellow skiers: “One who goes in circles for fun.”

There is a circular, repetitive quality to The Last Winter. Fox goes to a far-flung, typically cold place and asks locals to tell it to him straight: Is winter doomed? If so, when? The mountain dwellers shrug; they have more immediate concerns. The scientists offer grim models and dispiriting summaries of their data but, being the cautious professionals they are, mostly demur from pronouncing a fatal diagnosis. Then he rides this narrative chairlift up again to another high latitude or elevation spot and slides back down on similarly wistful terrain.

Advertisement

Fox visits local ski legends in the North Cascades of Washington; flies to Switzerland to interview climate scientists; travels by helicopter, skis, and snowmobile to a research camp on an Alaskan glacier; and rides a dogsled for a few days in Greenland before hustling back to Brooklyn to beat the Covid lockdowns in March 2020. The total effect is like sitting through a neighbor’s slideshow about his dystopian vacation. Descriptions of inns and airports and meals with scientists are interspersed with gloomy observations of once-wintry places that have become unrecognizable.

We get the gist quickly: pretty much everywhere Fox goes, winter is getting shorter, warmer, less reliably snowy. What we aren’t shown is the havoc these trends will wreak on the 98 percent of the world’s people who have never been on a pair of skis, much less all the nonhuman life that has evolved in sync with winter’s once-reliable rhythms.

The word “winter” comes from an old Germanic word that means “time of water,” a reference to the seasonal snows that blanketed the midlatitudes. Worldwide, two thirds of irrigated agriculture depend on mountain runoff. One might expect a chapter titled “The Great Melt Has Arrived” to address the implications of this global crisis for the nearly two billion people in Asia whose water in the dry season comes from Himalayan snow and ice. But it gets only a couple of cursory mentions throughout the entire book.

Instead, the chapter chronicles Fox’s ski tour of Italy’s Dolomites, following a twenty-five-mile village-to-village circuit with a colorful local guide, an old colleague from Powder, and two professional skiers, fueled by espresso and tagliatelle with venison ragù. “Our mission was to document Alpine winter life for a week in February,” he writes, “deduce how it had evolved, and project what would happen to it when winter was gone…. Porters would deliver our luggage every night to the foot of our beds. The Alps were a good case study.” But of what, exactly? Of the ongoing loss of winter as a playground?

Fox’s rhetorical choices throughout the book often minimize why these climatic changes matter. What is really at stake in this Great Melt is only gestured at.1 He recites the requisite data on declining snow cover and projections of ski resort closures in the second half of this century, but these are inserted term paper–style into chapter-long profiles of characters like Bird, an eccentric big-mountain skier—presumably one of the “journeymen” or “mavericks” of Fox’s subtitle, somehow trying to “save the world” while swooping down couloirs in Chamonix.2 Fox’s visceral reaction while touring the Alpine Museum reveals the main concern motivating his book:

You can’t take winter away from our children. On top of the worldwide cataclysm the Great Melt would bring, you can’t take away skiing, pond hockey, sledding, ice fishing, snowball fights, and thawing out in front of a fire with a mug of hot chocolate…. I wondered if winter would become mud season by the time Grey [his daughter] reached my age. I wondered what would replace the tangle of eleven hundred ski resorts that now occupy the Alps.

The Last Winter is climate science for ski bums—less call to action than a lament written for fellow skoryangspa. Fox’s book Deep: The Story of Skiing and the Future of Snow (2013) was written on the hopeful premise that skiers are the ideal demographic to agitate for climate action. He profiled a professional snowboarder named Jeremy Jones, who in 2007 founded the nonprofit Protect Our Winters (POW—a winking reference to the shorthand for fresh powder), which aimed to turn winter recreators of all stripes into climate activists. Fox later wondered in a 2019 New York Times op-ed why the “snow lobby” never materialized, professing his shock

that the ski industry and the alpine 1 percent it serves have not led the charge to slow climate change—if not to keep the climate safe for their progeny, then at least to save the snow outside their resorts and chalets.

The failure of Aspen or St. Moritz to emerge as hubs of climate activism is, I would submit, one of the least surprising developments in the brief history of climate politics. And the reasons go beyond the fact that skiing is a very energy-intensive pursuit, what with all the artificial snowmaking, heated sidewalks, and chairlifts. The resorts’ business model rests on luring affluent people to travel long distances. (The richest 20 percent of the world’s people take 80 percent of all flights; nearly half of all energy used for vehicle transportation and three quarters of energy used for air travel is consumed by the richest 10 percent.) Neither the industry nor the individual has strong incentives to turn activist.

The resorts with resources are pivoting to four-season activities: zip-lining, paragliding, tubing, indoor water parks. For many among the “alpine 1 percent,” maintaining the economic status quo is a higher priority than preserving snow. The thinking recently summed up in one writer’s widely shared tweet—positing that “the demise of skiing in the Alps will prove to be far more consequential to the rich world’s awareness of climate change than news that one third of Pakistan is underwater”—vastly underestimates the ability of the rich to compartmentalize the threats of global warming. If there’s not enough snow in Stowe or Zermatt over the school holiday, well, how about a trip to Palm Springs or Ibiza instead?

Fox suffers from a deeper confusion here—a misalignment of values. He makes the mistake of assuming all patrons of ski resorts love winter the way he does; skiing, he wrote in Deep, is the source of “the most transcendent and vital sensation I’ve ever experienced.” For most people, though, a day on the slopes is a diversion rather than a mystical experience, less like a meditation retreat than a Broadway show. Successful social movements must be built on stronger stuff. As for Fox’s own politics, the closest he gets to any kind of policy discussion in The Last Winter comes when he sees solar panels mounted on a two-seater bike in Switzerland: “Our best chance of survival is to change the way we create and consume energy immediately. It was happening here; I wondered why it was lagging so far behind in the United States.” Perhaps it has something to do with decades of misinformation pushed by fossil fuel interests seeking to sow doubt about climate science, and with outright and ongoing hostility to any kind of meaningful climate action by one of our two major political parties.

Fox’s efforts to get his stoke-seeking tribe riled up about climate change are laudable, and his grief over the mud-speckled forecast is sincere. I share his wish that our children could experience winter the way he and I did. Skiing—whether of the downhill, cross-country, or backcountry touring variety—can be a wonder-filled way of moving through the natural world. The loss of that opportunity for millions of people is worth lamenting. So are the consequences for those whose jobs depend on winter tourism.

Yet I’m not sure that “swashbuckling” mountain guides, “badass” big-mountain skiers, or “bon vivant” glaciologists actually have that much to teach us about winter. These are the people our culture tends to associate most with the cold, and the North Face ad copy (trademarked slogan: “Never Stop Exploring”) suggests we should admire them precisely for pushing the boundaries of what humans can do and where they can go (with a heavy assist from helicopters, gondolas, intercontinental flights, and snowmobiles). The irony is that this ethos is deeply antiwinter, because winter is all about living within limits.

For most organisms—the ones that don’t migrate—winter is a fallow time. It is the season of humility. That lung-rattling shock of cold upon walking out the door is a useful reminder that you won’t last long unless you accommodate yourself to the season’s demands. A stern teacher, winter insists we slow down, stay put, look around, conserve our energy, and find other forms of nourishment than summer’s hectic, heedless pursuits. Winter is the hard season. But one thing that is easier in winter is perceiving what’s important.

After New Year’s in Vermont, the snow came and went. We hunkered down at home. In midwinter the slopes were mostly bare, a glimpse of “normal” winters to come. (In Burlington, it proved to be the third-warmest winter on record.) For me, it brought solastalgia—described by Glenn Albrecht, the Australian philosopher who coined the word, as “the homesickness we feel while still at home”—and nagging thoughts of Robert Frost’s challenge: “What to make of a diminished thing.”

For my daughter, though, it was just winter. Here on the flanks of the Green Mountains, the snow that did fall tended to persist in the shade of the woods around our house—long enough, at least, for her to put on her skis and make trails between the trees, moving under her own power, in search of her own experience of winter.

-

1

I addressed some of the repercussions in these pages in “A World Without Ice,” The New York Review, May 24, 2020. ↩

-

2

One learns to be wary of climate books whose titles include the words “save the world.” ↩