In “Looking Out,” an early episode of the Pulitzer Prize–nominated podcast Ear Hustle, hosts Earlonne Woods and Nigel Poor interview Ronell Draper, who goes by Rauch (pronounced “Roach”). About forty years old and incarcerated at California’s San Quentin State Prison, Rauch is known for his aromatic dreadlocks and his menagerie of pets: gophers, rabbits, a praying mantis, snails, swallows—even, for a time, a tarantula. It probably goes without saying that pets are not allowed in prison, but some corrections officers apparently look the other way.

As a child, Rauch tells Woods and Poor, he was removed from his mother’s custody after she tried to drown him in a bathtub. When he was ten, he was moved from an orphanage in South Philadelphia to a group home, and he was homeless by the time he was a teenager. He sometimes stayed in friends’ houses without their parents knowing he was there—an experience that made him feel like a roach, hiding in the shadows. But it was during his stay at the group home that he began surrounding himself with animals, including lizards, kittens, pigeons, and dogs. “I wanted all the animals to be my companion and friend,” he says softly. “I hang out with these guys, or girls…. I don’t own them.”

Some Ear Hustle interviews are conducted in the prison yard, with ambient sounds of men talking or playing basketball. Others, like “Looking Out,” are conducted in a studio at San Quentin. The podcast features music by Antwan Williams and occasionally includes additional sound effects, like the echoing plunk of water dripping while Rauch recalls his mother’s attempt to drown him. But the soundtrack recedes when Rauch describes why he’s in prison:

I got into crime for survival, and I was hurtin’, and I thought it was a way to get back at people. This was the way to make them feel the pain that I felt. Then it slowly became just a part of what I did. I’m incarcerated for second-degree murder. We got in a fight with someone and I ended up killing him.

Here Poor advises listeners that she and Woods are not investigative journalists. “We invite people to tell us their stories,” she says, “and there’s really only so much fact-checking we can do.” The audio cuts back to Rauch. “I take care of animals because they teach me what I can’t learn from people,” he says. “It’s unconditional affection or appreciation.” Poor comments: “He has such a powerful urge to take care of critters—to nurture, really—and we all have that urge.” Woods agrees but corrects her terminology. “Most guys aren’t going to call it ‘nurturing,’” he says. “They’re gonna say ‘looking out.’”

Although “Looking Out” was only the third episode of Ear Hustle—the term is slang for eavesdropping—Woods and Poor had already found the podcast’s rhythm and tone: direct, compassionate, and curious about the granular details of prison life. Now in its eleventh season, Ear Hustle was launched in 2017 by Poor, who teaches at San Quentin, and Woods and Williams, who were serving lengthy prison sentences and have since been released—Woods in 2018 and Williams in 2019.

A visual artist and professor of photography at California State University, Sacramento, Poor had been volunteering at San Quentin since 2011 through the Prison University Project (now known as Mount Tamalpais College). After teaching a history of photography class there for three semesters, she began spending time in the prison’s media lab, where she worked with a group of incarcerated men on a project called Windows & Mirrors, in which they recorded conversations with other men serving time that were aired on San Quentin’s closed-circuit station. Woods was a volunteer in the media lab, learning to make and edit videos and lending a hand where he was needed. This eventually included assisting Poor with technical issues and helping her navigate the egos and infighting among the men in the lab. “He was a slow reveal,” she says, a friendly but shy man who rarely spoke. Over time they began talking, and the idea for the podcast took shape.

The fact that San Quentin has a media lab at all is unusual. Unlike many prisons, it offers a number of vocational and educational programs, including Mount Tamalpais College, which enables inmates to earn a college degree while serving time, not to mention the long-running San Quentin News, staffed by incarcerated writers and editors. In 2007 the Discovery Channel ran a ten-week film school at the prison; when it ended, Discovery donated the equipment, which constituted the media lab until the arrival of Ear Hustle. In 2016 the podcast won a contest organized by the network Radiotopia. In addition to national distribution, Radiotopia awarded them $10,000, which Poor used to buy new equipment for the lab. Still, it’s a far cry from a high-tech, soundproof recording studio: the Ear Hustle area, as Poor describes it, is a noisy, cement-walled, ten-by-twelve-foot space with no Internet access and a ceiling prone to leaks.

Advertisement

Ear Hustle offers a kaleidoscopic view of life inside San Quentin by delving into small-scale subjects, from the costs and frustrations of a fifteen-minute phone call to figuring out how to get coconut oil or coffee from the prison supply catalog to parenting while incarcerated to completing a marathon by running 105 laps around the scruffy prison track. These modest stories allude to larger structural issues like prison reform and sentencing policies without addressing them directly. More than eighty-five episodes in, Poor and Woods have managed to maintain a predominantly light, inquisitive tone. Some episodes, though, are quietly devastating.

In “Firsts,” from 2018, Adnan Khan, who’d been in prison since 2003, spoke about the first time his mother came to visit him, more than ten years after he was incarcerated. She’d tried to come once before but he refused to see her. This time he prepared carefully, ironing his clothes and anxiously choreographing what would be his first hug in more than a decade:

I didn’t know if my hand goes around her shoulder or her neck. I didn’t know if it went diagonally, like two forty-five-degree angles? And then I was like, you know what? I’ll let her lead. Like, this is my mom, right? And I don’t know how to hug my mom.

When she visits they do hug, awkwardly—and that brief embrace is the beginning of a story about the fundamental importance of touch, the visceral pleasure of an ice cream that she buys him in the visiting room, and his discomfort in allowing her to witness the restrictions that define his movements.

In “Boots and Max,” an episode from March 2022, Poor and Woods interview an incarcerated man named Boots about his romantic involvement with Max, who was also serving time at San Quentin. “I couldn’t believe that someone as amazing as him would take an interest in me,” says Boots. “He’s got a beautiful smile…this rich voice.” When Poor asks Boots to describe himself, he promptly says, “I’m short, fat, and ugly.” He adds, laughing, “I’ve got these tiny little ears that look like chicharrones.”

His relationship with Max is not without significant risks. Prisons, observes Poor, are some of the most homophobic places she’s ever been, and Woods agrees: “There are definitely a lot of guys in prison who aren’t okay with people being gay.” Max gets beaten so badly on the yard one afternoon that he’s hospitalized for twenty-three days. “I don’t have a history of being loved and appreciated and cared for, so having that, and then losing it,” says Boots—“I had no idea how to deal with that.” He’d go out into the prison yard with handmade signs reading “Come back” that he’d hold up toward Max’s window in the prison hospital. Max did, eventually, and even shared a cell with Boots for eight months before being released on parole just prior to the start of the pandemic. Poor and Woods had intended to interview him too, but San Quentin was on lockdown while they were making the episode, so they weren’t able to reach Boots in order to be connected with Max.

The pandemic was devastating for the men inside San Quentin. Seventy-five percent of the population was infected, prompting a state appeals court to call it “the worst epidemiological disaster in California correctional history.” In December 2020 Woods and Poor spoke to Juan “Carlos” Mesa, who had just been released from San Quentin but had still been inside during the first outbreak that spring. He described the deep sense of fear and anxiety in the prison. “I’m in a giant coffin with a bunch of other people,” he remembers thinking. “There’s no going anywhere.”

Because Covid restrictions closed San Quentin to visitors for much of the past three years, Woods and Poor had to rethink the way they produced the podcast. They made occasional field trips—to the CAL FIRE Ventura Training Center, which trains formerly incarcerated men to become firefighters, for example—but, perhaps inevitably, the stories produced during the lockdowns sometimes lack the intimacy and focus that make the in-person interviews so absorbing.

While Woods and Poor devised workarounds for the podcast during lockdown, they also collaborated on a book, and in 2021 they published This Is Ear Hustle, which includes transcripts of Ear Hustle interviews interspersed with first-person narratives by the cohosts. Woods writes about growing up in South Central Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s, where he went from selling joints for a dollar when he was fourteen to selling cocaine to the attempted robbery that landed him in prison in 1997 at the age of twenty-six. Poor recalls struggling with dyslexia growing up in New England and finding her way to becoming an artist. The book will be most appreciated by readers who know the podcast—think of it as the liner notes for an album, ideal for people who already love the songs. Ear Hustle’s success is rooted in large part in the camaraderie and warmth of its two hosts, and the book fills in their individual backstories for longtime listeners. Even for fans, though, the printed interviews can’t compare to the show, which captures the intimacy of the conversations and emotion in the voices of the people being interviewed.

Advertisement

A 2020 episode called “The Trail,” for example, about a brutal sexual assault, is included in the book, where Poor explains how the Ear Hustle team structured it. She and coproducers Rahsaan “New York” Thomas and John “Yahya” Johnson interviewed an incarcerated man named Leonard about a rape that he committed on a hiking trail near Carmel, California, in 1990. It’s one of the rare instances in which the interview elicits little sympathy for the incarcerated man, who in this case seems unrepentant and also to have convinced himself that his victim had forgiven him. At one point Johnson observes, “In my view, he’s not holding himself accountable for this crime at all.”

After the interview with Leonard was recorded, the prison went into Covid lockdown, and Poor and Woods decided to expand the story in a way they hadn’t done before: by interviewing the survivor of the assault. After they discovered that the victim, Marah, had died of cancer in 2004, they contacted her sister, Pat. Given the subject matter, Poor explains in the book, they decided that Poor should conduct the interview by herself. The transcript is included in the book, and it’s a heartrending text, not least because of the tender way that Pat describes caring for Marah as she was dying.

But the emotional impact is magnified in the podcast itself, in which we hear Poor’s voice catch after Pat describes washing her sister’s body after she died, and we hear Leonard’s callous indifference as he describes his premeditated, violent assault. We also hear Terri Dorman, who was the district attorney’s victim advocate for Marah, read the victim impact statement that Marah had read in the courtroom. Marah called the attack “an act that is repugnant to God, man, and woman,” and added: “This kind of violence has [had] unimaginable trauma on me…. I pray that the assailant, the man who hurt me, will realize that in hurting me he has hurt himself.” It’s hardly, Poor observes, a statement of forgiveness.

Ear Hustle doesn’t gloss over the violence committed by some of the men incarcerated at San Quentin. But neither do the hosts regard the people they interview through the lens of their crimes alone. There’s also an acknowledgment, largely unspoken, of socioeconomic and racial disparities. As Woods observed after listening to Rauch talk about his childhood in “Looking Out,” “Everybody don’t grow up the same.”

In the first chapter of This Is Ear Hustle, Woods writes that as a boy he looked up to the local detectives in his neighborhood—they were coaches and mentors—but that changed when he was nine. He was picked up by the police for lifting the gate of a railroad crossing after a train had passed in order to let some cars cross, thinking he was being helpful. They handcuffed him and drove him to the station, where they left him crying alone in a holding cell for hours, begging to use the bathroom. He didn’t want to get in trouble for peeing on the floor, so left without any other choice, he recalls, “I took off my checkerboard Vans and urinated in them.”

As devastating as the description of this incident is in the book, when Woods recounts it in a May 2021 episode of the podcast called “Cracked Windshield,” the sense of anguish is multiplied because it’s part of a larger conversation, recorded one year after the murder of George Floyd, among Woods, Johnson, Ray Ford, Troy Talib Young, and several other incarcerated men about their early experiences with the police. It’s an accumulation of stories of mistreatment, beginning when these men were as young as nine.

Even Lieutenant Sam Robinson, the public information officer for San Quentin until his retirement at the end of 2022—whose job was to authorize all of the media produced in the prison, as well as any media that came into it—recalls being mistreated by police. Throughout the first ten seasons, listeners heard his voice at the end of every episode of Ear Hustle, and his comments were generally good-humored and brief: “I’m Lieutenant Sam Robinson, and I approve this story.” But here he speaks at length about being put in handcuffs, facedown on the ground, when he was nineteen years old because someone wrongly accused him and his younger brother of stealing a boy’s baseball cards. “I think that every Black man has a story, right?” he says.

While the podcast generally steers clear of advocacy in favor of storytelling, the book devotes an entire chapter to Woods’s fight to repeal California’s three-strikes law, which he calls “the most oppressive law since slavery was legal.” Enacted in 1994 in response to the murder of a twelve-year-old girl, Polly Klaas, the law imposed a sentence of twenty-five years to life if the defendant had two prior convictions for crimes defined as violent or serious by the California Penal Code. It was originally designed to keep violent offenders in prison, but the result was that a disproportionate number of Black and Latino men regularly wound up with life sentences for nonviolent crimes.

Woods himself was directly affected by the law: when he was convicted of second-degree robbery in the late 1990s, the fact that he had two earlier concurrent convictions—for kidnapping and robbing a drug dealer when he was seventeen years old—meant that he was sentenced to thirty-one years to life. In 2012 the Three Strikes Reform Act passed, eliminating life sentences for nonserious, nonviolent crimes. Woods and Johnson filed a ballot initiative to repeal the three-strikes law entirely in 2022, but they failed to get enough signatures to put it on the ballot last fall.

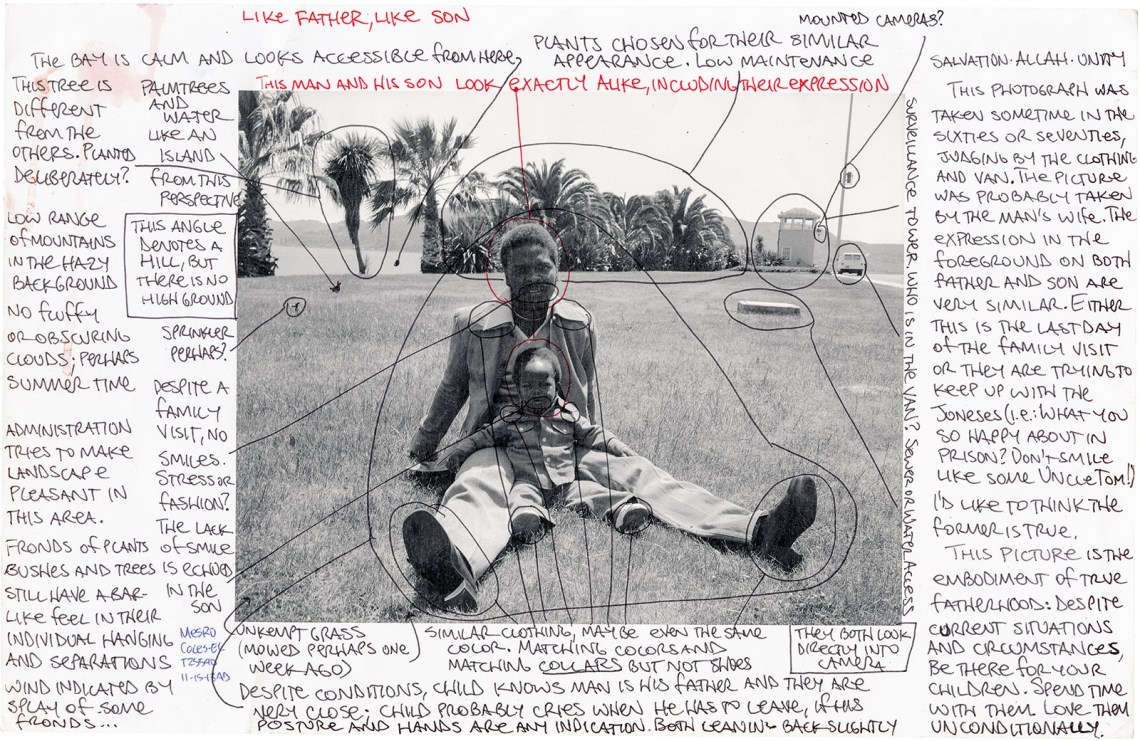

Poor’s advocacy is less direct. She describes herself as someone who “loves to follow odd clues and seemingly random coincidences.” In 2010 several letters from the same person at San Quentin were misdelivered to her house. She brought them to their intended address, and while she never met the recipient, her interest was piqued. When she heard that San Quentin was looking for volunteer teachers, she signed up to teach the history of photography. She developed an assignment that she called “mapping,” in which she asked her students to annotate copies of photographs that she brought in—writing directly on them about what they saw in the image and what it meant to them. She also invited them to use the photographs as prompts for stories. Her book The San Quentin Project includes some of the work they produced.

One of the photographs that Poor shared with her students was Joel Sternfeld’s McLean, Virginia, December 1978, which shows a pumpkin stand on a small farm with a burning house in the background. The house was actually part of a firefighting drill, though that isn’t apparent in the image or its title. A spread in The San Quentin Project reprints a short story that one of her students, Frankie Smith, wrote about the picture, in the pained voice of a farmer losing his home in the fire: “It’s the leaving behind in graves topped with lavender and morning glories, where my great grandparents lay that causes a deep void in my heart.” Smith included the ingredients for what he called “Mrs. McLean’s Famous Homemade Pumpkin Pie” and decorated the lower-right corner with a colorful grid pattern.

Such annotated artworks—which also include images by William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, David Hilliard, and Lee Friedlander—illustrate the students’ observational powers and creativity. But the majority of the annotated photographs included in The San Quentin Project are from the prison’s own archive. After Poor began teaching at San Quentin, Lieutenant Robinson showed her a trove of hundreds of four-by-five-inch negatives taken by corrections officers there between the 1930s and the 1980s, and he allowed her to make prints from them. Many document the aftermath of violent episodes, evidence of escape attempts, or injuries, while others show families on visiting day or men participating in regulated leisure activities. Aside from brief labels on the negative sleeves, there was no information about who the subjects were or why the photographs were taken. It’s unlikely, though, that the men were asked for permission to be photographed.

Photography has often been a tool of the carceral state. Mug shots, wanted posters, crime scene images, and so-called perp-walk pictures have shaped perceptions of incarcerated people in the outside world while they’ve been used to monitor people on the inside. Poor provided the men in her class with the opportunity to give those photographs a different meaning. As Lisa Sutcliffe, a curator at the Milwaukee Art Museum who organized an exhibition based on The San Quentin Project in 2018, points out in the book, “Because those who are incarcerated are intimately familiar with San Quentin’s rituals, culture, and unspoken rules, their interpretations and narratives offer unique perspectives.”

In a photograph labeled “Mother’s Day, May 9, 1976” (see illustration on page 64), a man in a wide lapel suit sits on the grass, posing with a toddler who sits in front of him, his small hands resting on the man’s outstretched legs. In “mapping” the image, George Mesro Coles-El gives a poignant reading. “Despite a family visit, no smiles,” he writes in the margin. He points out the surveillance tower in the background, noting that there are “no fluffy or obscuring clouds,” which makes him think it might be summer. “This picture is the embodiment of true fatherhood,” he concludes. The image, along with Mesro Coles-El’s annotations, asks readers to remember that people in prison are also parents, children, siblings, spouses, friends—human beings whose confinement affects a web of other people.

Some of the students’ observations can be piercing: they know from experience what they’re looking at. “A sad show of carelessness and apathy here, even this long ago,” writes Sha Wallace-Stepter on an aerial view of a courtyard where a chalk outline had been crudely drawn on the ground. The photograph was labeled “Heckman suicide, December 28, 1964.” Wallace-Stepter’s comments underscore the apparently cursory nature of the attention paid to the death of a human being within the prison walls. In drawing our attention to it, he asks us to recognize and reckon with it.

“When you look at these images of San Quentin, spanning decades of institutional life,” Rachel Kushner writes in an essay for the book, “remember that these bodies and their traces, these people…were, are, and will be a surplus of human life that an institution cannot reduce to objecthood, no matter how willfully it tries.” The San Quentin Project also includes a foreword by the poet Reginald Dwayne Betts; conversations between Poor and two of her students, Ruben Ramirez and Michael Nelson; and two pieces of writing from class assignments, one by Nelson and the other by Mesro Coles-El. Nelson’s nine closely observed, handwritten pages comparing photographs by Hiroshi Sugimoto (La Paloma, Encinitas, 1993, from his Theaters series) and Richard Misrach (Drive-In Theatre, Las Vegas, 1987), written while he was in solitary confinement, speak to the lifeline that photography, and the class, offered him. “The photographs of the two picture screens were captured at different times and within different spaces,” he writes, “and are visually different, yet both share the same story and both relay to me the same message: that no one person is ever really alone, in their experiences and with their feelings.”

Ruben Ramirez is a particularly astute observer and beautiful writer. On an image labeled “Stabbing in gym, September 24, 1963,” he writes in longhand over the bare back of the stabbing victim, who leans forward, head down. In the photograph the arms of two people reach into the frame from each side; one seems to hold the man’s head up, the other rests a hand on his shoulder, offering comfort, or possibly helping him sit up. Ramirez compares the arms of those two people to “buttresses attempting to prevent the structural failure of a once proud castle,” and adds that one of those arms seems to convey, “with a reassuring soft touch,” that help is on the way.

Ramirez was released from San Quentin in 2017. Poor’s photography class, he says, changed his way of looking at the world: “I started getting into shadow, and then forms, and then shapes.” But the exercise of annotating the photographs also, he says, “sort of schooled me in my empathy.” Looking at the men in the images from the archive made him think about who they were and what they were going through, how they wound up in prison and what they were feeling. It could be said that schooling readers and listeners in their empathy is the animating force of The San Quentin Project and Ear Hustle. Both push past preconceptions with stories that bring individuals into view. As Ramirez says to Poor: “I’m trying to understand what you’re going through so that I can care for you.”