George Balanchine, the great choreographer and cofounder of New York City Ballet, who arrived in the United States in 1933, almost always had a girlfriend—often a few.1 His first American girlfriend, Holly Howard, apparently had four or five abortions in their first year together. Is it possible to get pregnant four or five times in a single year? Maybe so, because Howard’s mother threatened to have Balanchine deported. Eventually, he met his destiny in the form of a different woman, an extremely beautiful nineteen-year-old German-Norwegian, Vera Zorina, who at that time was just coming off an affair with Léonide Massine, the only man Balanchine seems to have regarded as a serious rival (for jobs as well as women) and whom he consequently hated.

Each day, as Massine crossed the country on tour with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo (he was its ballet master), he would set a timer: so-and-so minutes with his wife, so-and-so minutes with Zorina. Massine reportedly didn’t mind this arrangement. Zorina did and finally she slit her wrists in a Florida hotel where the company was staying. Soon after that, she switched to Balanchine, and the two were married in December 1938. But she seems never to have forgotten Massine, and she did not hide this fact from Balanchine. All around the apartment she came to share with him, she installed photographs of Massine. Balanchine fell crazy in love, probably the more so because she had been Massine’s before.

Zorina is the first big chapter in Jennifer Homans’s chronicles of Balanchine’s love life: how he bought her an ermine coat; how he had a beautiful pink house built for her on Long Island; how, once they separated, he would stand, grieving, under the window of her apartment at night. But here Homans makes a nicely iconoclastic point. Balanchine, always a gentleman, claimed that he never left any one of his wives. Every one of them threw him out, he said. Not so, says Homans. He left one of them: Zorina, his great passion. She never loved him, Balanchine later claimed. What she wanted, he said, was celebrity: Broadway and Hollywood, diamond bracelets, big-time boyfriends. When she was with Balanchine, she was also toying with Orson Welles and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. On this subject, her lack of real interest in his work, Balanchine wrote to her, “I promise myself to be a producer”—that is, the person who would decide what kind of ballets he would make—“and I am on the way, and I will be.” Zorina later complained that “if George had said to me ‘The hell with Hollywood! Come and dance with me,’ our lives might have been very different.” But he never did, presumably because he didn’t believe she could make something of the kind of dances he wanted to produce.2

The breakup with Zorina comes at the middle of Homans’s narrative and is its turning point. The suffering he endured over her in 1940–1941, the year they separated, actually saved him, Homans believes:

He was not artistically derailed by bad times. It was the good times—sunny Hollywood, bountiful Broadway, pink house, beautiful wife—that threatened his gift, and somehow he never let them last. Like an injured animal, he moved on and smelled out another woman, another situation, another way to make dances. Rupture was painful, but not destructive. He had an instinct for his own genius, and loss and unattainable or unrequited love seemed to stand at its heart.

At that time, too, he rejoined Lincoln Kirstein, from whom he had been separated for most of his Broadway and Hollywood years. Kirstein, through his friend Nelson Rockefeller, got Balanchine, with whatever group of dancers he could muster, a government-sponsored goodwill tour to South America, and now Balanchine returned to his heart’s home: classicism. For this tour, he revived Apollo, his first work of “neoclassicism.” Also for the 1941 tour, he created Concerto Barocco, to Bach’s Double Violin Concerto in D Minor. This ballet more or less epitomizes his modernist classicism. In it, he married Bach’s fantastic syncopations to the “swung” style he learned from Broadway and Hollywood musicals, often from Black dancers.3 Following Bach, he also crafted a slow second movement to operate as a kind of tragedy offsetting the comedy, as it were—brilliance, speed, cheer—of the first and third movements.

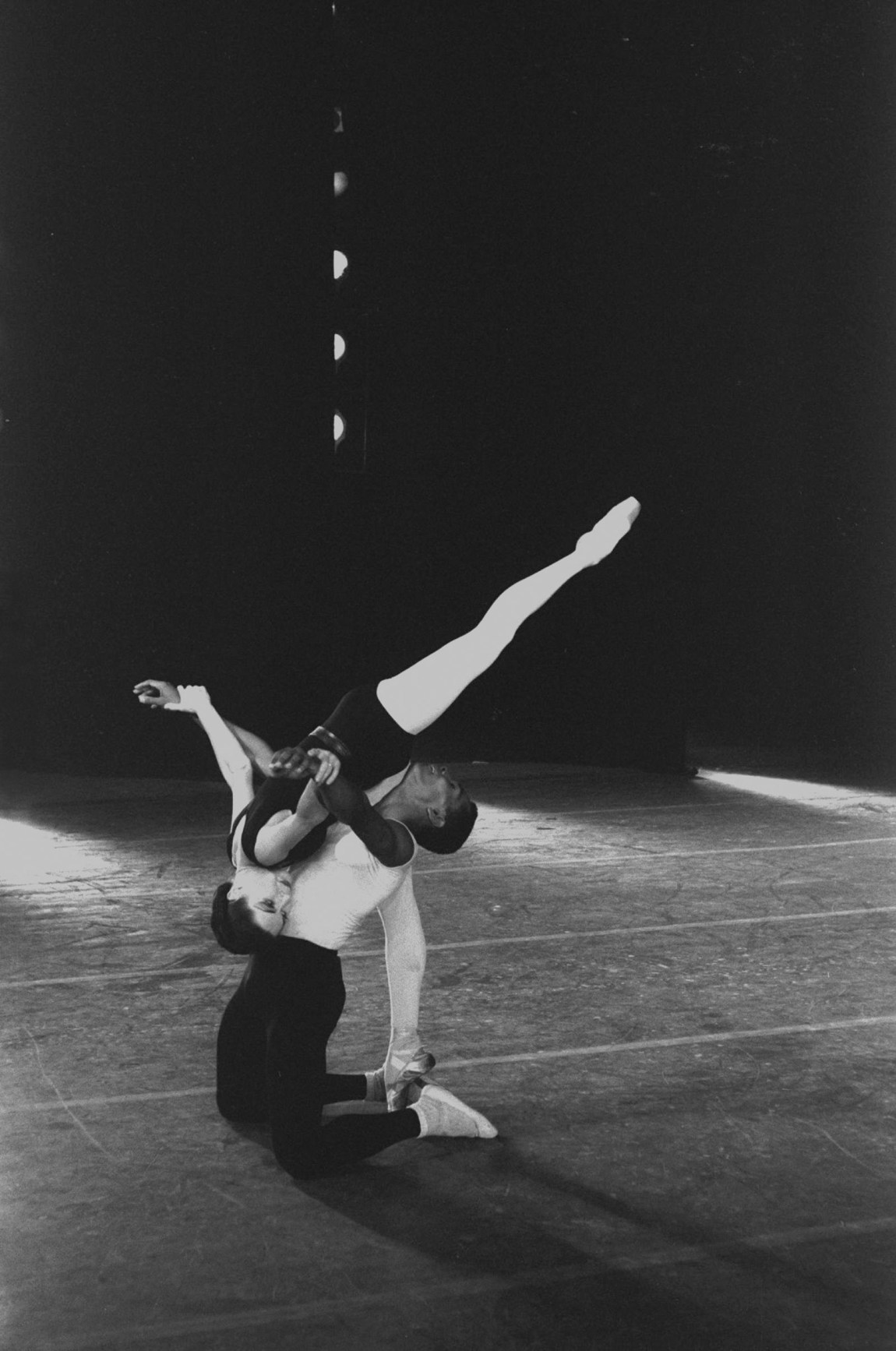

In Barocco’s second movement the eight women who were the backups in the jazzy outer sections became the chorus of some darker drama. They bowed, they turned, they knelt, as the lead woman, partnered by a man who suddenly appeared at the beginning of the movement and vanished at the end, was borne into the air over them. During the theme’s crescendo, he lifted her five times in arabesque, in a vaulting parabola, and then brought her down slowly, point first—a “plunge into a wound,” wrote Edwin Denby, the Herald Tribune’s reviewer. I have never been able to explain to myself what the wound was that Denby was referring to. (Or why he said there were five lifts. In my time, I saw only four.) I think I know, though. This is the other “neoclassical” thing about Balanchine: like Mozart, he often gladdens your heart in order, then, to break it, whereupon, in the next movement, he tells us that we have to go on living anyway.

Advertisement

Perhaps as a side effect of this new, sobering clarity, Balanchine in the 1940s began to change his costuming practice. In 1945 the women in Concerto Barocco wore “practice clothes,” in this case probably plain black tunics. Soon he was costuming many of his new ballets, and recostuming important old ones, in tunics (often white, as in Apollo and today’s Barocco) or leotards (usually black, as in Agon or Stravinsky Violin Concerto). Some people saw this as a modernist gesture, as if the dancers had been newly dressed by Mies van der Rohe. Balanchine’s detractors, as usual, saw it as an act of withholding on his part. Still others saw it just as a species of theatrical wisdom. He was showing us things that buttons and bows could only obscure.

As Balanchine, in this period, hammers out his mature style, Homans is right there behind him, with full discussions of the matters that now became most important to him, above all time, music, abstraction, and faith. These are weighty subjects, and when Balanchine seems to think he is looking God directly in the face, Homans’s writing—like Kirstein’s, facing the same problem—can sometimes become more exalted than clear, but from what I can tell, she never avoids anything because it looks too hard. “The real world is not here,” Balanchine said in 1972. How are you supposed to get that onto the page? She tries.

In other circumstances, too, she is an excellent writer, with expert pacing. A Philosophy 101 section will be followed by a shovelful of hot gossip (Kirstein went to bed with his brother? Say it ain’t so!) and by a bundle of good quotes. Balanchine’s political opinions are always bluntly stated. For the USSR, he expressed an unstinting hatred from the day he left in 1924—before, actually—to the end of his life. For the tsarist regime that preceded it, he felt an ill-placed nostalgia, one that supported his half-political, half-religious idealization of what he saw as the “real world” standing behind his suffering homeland. Indeed, he was said to have modeled New York City Ballet on it: “One man, one rule.”

It is often claimed that he bullied his female dancers and scolded them if they gained weight, though in fact he also scolded them if they lost weight. (He was always throwing out Alexandra Danilova’s diet pills. Zorina’s too. “Eat more,” he wrote to her, “otherways you will loos your beautiful bust.”) He advised others of his female dancers, at all costs, never to get married. If you do, he said, you will just become “Mrs. Him”—not to speak of pregnant. All babies, he said, looked like Dwight D. Eisenhower. Of course, it wasn’t the babies’ looks that annoyed him but their tendency to interfere with their mothers’ work at NYCB. Two dancers whom he adored, Diana Adams and Allegra Kent, were repeatedly sidelined by pregnancies. One could say that it was partly because he could not have Adams that he developed his last great obsession, Suzanne Farrell, a prodigiously talented dancer whom he took into the company when she was seventeen, on Adams’s recommendation, and whose image dominated his waking mind to the end of the decade—perhaps to the end of his life.

It was the Zorina scenario all over again, but different. For one thing, Balanchine was married this time, to a widely beloved dancer, Tanaquil Le Clercq, who, to make things worse, had been immobilized by polio in 1956 at twenty-seven. Furthermore, the age difference between Balanchine and Farrell was not just extreme but almost bizarre. Balanchine had been thirteen years older than the teenage Zorina and twenty-five years older than Le Clercq, but he was forty-one years older than Farrell. He could have been her grandfather.

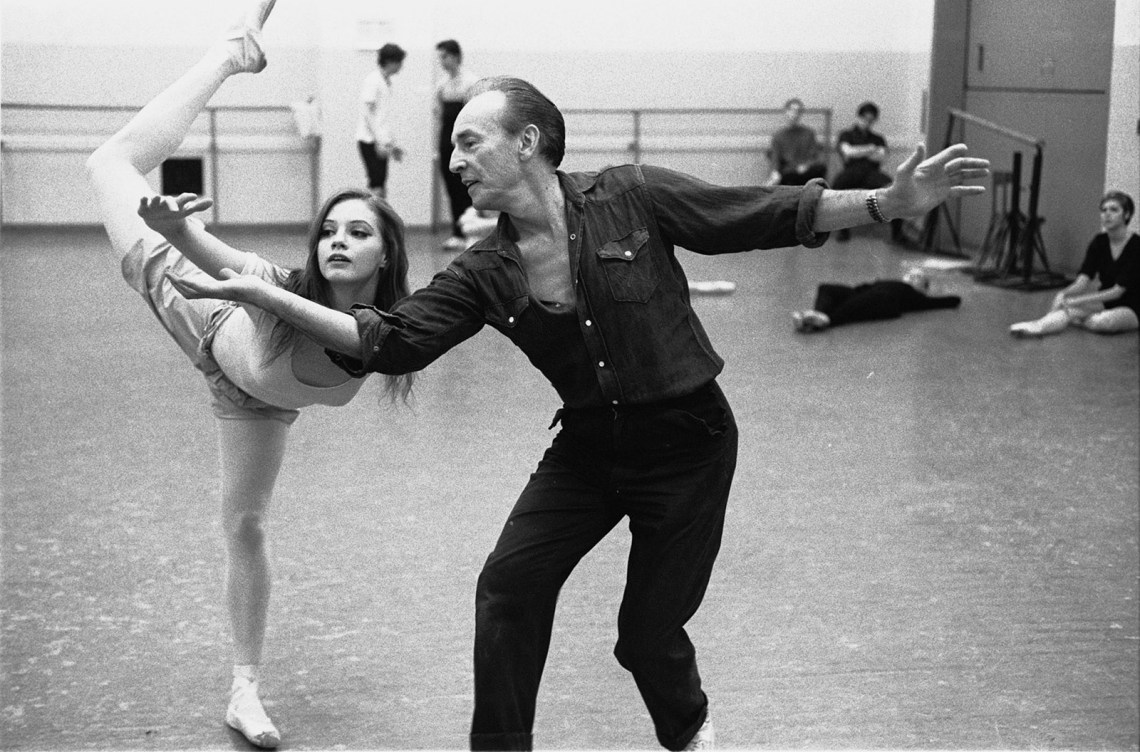

Such pairings had certainly occurred before, but this one was on public display. Anyone who wanted could go over to the Tip Toe Inn on 86th and Broadway, Balanchine and Farrell’s favorite after-the-show dinner spot, and watch the great man doing the New York Times crossword puzzle with the cute, ponytailed Farrell before he walked her home. And that is not to speak of the fact that, unlike his romance with Zorina, Balanchine’s relationship with Farrell was something that grew within a company, his company, and had the power to harm it. Balanchine was not discreet. When Farrell finished dancing for the evening—and she danced most evenings, as he wished—he would exit the theater, leaving his company to dance the remainder of the program alone, without his supervision (his care, his corrections), so that he could take Farrell to dinner. Before, whenever the company was performing, he was watching from his regular spot in the downstage-right wing. “I turn out the lights,” he famously said. Not anymore.

Advertisement

Another irritant was casting. In any given season, the roll call of dancers scheduled to perform in the upcoming ballets was posted backstage approximately the week before. The assignments, of course, had already been reviewed—for leading roles, determined—by Balanchine. But now they were reviewed by Farrell as well. And Balanchine flat out asked her what she wanted to dance. “He wanted to see her in everything,” Homans writes. When once (and probably more than once) she changed her mind and decided that she wanted to dance in a ballet she had passed over on her first perusal of the casting, Balanchine just crossed out the name of the woman who had been assigned that role—and who perhaps was already rehearsing it in a studio down the hall—and inserted Farrell’s.

Company morale plummeted. Several important dancers quit. A few tried to persuade Farrell that she should just, please, go to bed with Balanchine. They thought this would restore his sanity. But Farrell was a serious Roman Catholic. In her 1990 memoir, Holding On to the Air (written with Toni Bentley), she says that outside the studio the two of them had no intimate contact, and that she didn’t need any. Their work together in rehearsal, as she experienced it, “was more passionate and more loving and more more than most relationships.” Furthermore, as she omits to mention, but Homans states plainly, a teenage girl may not have hankered after bed sport with a man in his sixties.

Finally, in 1969, Balanchine, on his way to an assignment in Hamburg, took a detour to Mexico, where he obtained a quickie divorce from Le Clercq. He seems to have assumed that Farrell would marry him once he was free. He was mistaken. Farrell took the opportunity of his absence to marry Paul Mejia, one of the very few dancers in the company, reportedly, who still liked her. (They had been dating in secret.) When Balanchine got the news in Hamburg, he went nuts. Summoning his assistant, Barbara Horgan, from New York, he seems to have detained her in the dining room of his hotel for a full day, drinking boilermakers, weeping, and yelling.

Eventually he returned to New York, and the showdown came. Farrell appears to have anticipated that, however unhappy Balanchine might have been about her marriage, she would retain the privileges—I like this, I don’t like that—that she had had previously. Maybe she would have. But as she apparently failed to expect, her husband would not be forgiven, ever. When one night, soon after the new season began, Mejia was not cast in a role that Farrell felt was owed to him—in Symphony in C, in which she too had a role, arguably the lead role—she sent Balanchine an ultimatum: either Mejia danced that night, or neither of them would. Then she sat down in her dressing room and began putting on her stage makeup, sure that her wishes, as always, would be honored. There came a knock on the door. It was Madame Pourmel, from the company’s wardrobe department. She entered with tears in her eyes, collected the Symphony in C tutu, and told Farrell that she would not be dancing that night.

As Farrell understood, that was the end. Bewildered, she and Mejia packed up their things and left the theater. Great dancer though Farrell was—and in these years, at the top of her game—it was not easy for her to find employment after she left NYCB. By now, Balanchine was a famous and powerful man. Many ballet directors had no wish to get on his bad side. Furthermore, Farrell wasn’t the only one in this story who needed a job. It was understood that whoever hired Farrell had to be prepared to hire Mejia as well. In the face of these difficulties, Farrell, over the next few years, sent Balanchine a number of brief, airy notes. Finally, in 1975, six years after her departure, she wrote to him straightforwardly, and without any sidenotes about Mejia, “Dear George, As wonderful as it is to watch your ballets, it is even more wonderful to dance them. Is this possible? Love, Suzi.” Balanchine’s resolve crumbled, and he invited her back.

She never regained her former prominence. Not only was she still married—she and Mejia did not divorce until 1998—but by this time Balanchine too had found a new dinner partner: Karin von Aroldingen, a German dancer, taller and more solidly built than his usual picks, whom he had hired in 1962. Once Farrell left, von Aroldingen all but auditioned for her position. She took Farrell’s accustomed place at the front of the barre in company class. Around her waist she tied the same kind of flowered shawl that Farrell had worn around her waist. She was even said to have acquired Farrell’s overbite.

According to Homans, von Aroldingen, though married and with a child, offered to rent an apartment for herself and Balanchine. Balanchine reportedly declined the invitation: “He said no, please don’t, really, he wanted to be alone.” For him, apparently, that kind of love was over. But maybe not, completely. In 1977 he bought a small condominium across from the house von Aroldingen shared with her husband and daughter in Southampton. Sometimes von Aroldingen spent the night in the condo with Balanchine; sometimes she stayed home.

What changes will this book, with its unstinting discussion of intimate matters, make in our view of New York City Ballet? There has always been some speculation about Balanchine’s sexual habits; in time, this talk was abetted by the memoirs of his intimates. His fourth wife, Maria Tallchief, wrote in her 1997 memoir of how hastily Balanchine arranged for the two of them to have separate beds after they were married in 1946. When they went their own ways—pretty soon, in just a few years—this was registered with the Catholic Church as an annulment, not a divorce. That is, there may have been a problem about the consummation.

Some people proposed that perhaps Balanchine had special interests. In his 1957 Agon, he was one of the first ballet choreographers to use fully spread female legs—en face, or seen from the front (and covered, needless to say). Many choreographers have since used this maneuver. (What would Karole Armitage have been without the crotch?) God bless him, many of us thought. There it all is, the whole story of the female body, and unashamed—indeed with the pelvis featured, to show that it is the engine of movement. Men can’t do this. Only women can.4 (Women give birth and therefore they have to be able to spread their legs.) It seemed that we were at last seeing the full extent of what female dancers could do, as design and suggestion.

Homans does not avoid discussion of what are claimed to have been Balanchine’s favored sexual activities. But what she mentions are by no means exotic practices. Sex with the help of fingers, sex with the help of tongues: people have been doing these things for a long time. There is a poignant note here, though. Because of his love of younger women, Balanchine was very concerned about aging. Homans says that he was a longtime client of Swiss health clinics and took virility potions, including serum injections from bulls’ testicles. The illness from which he died, or at least the proximate cause, was ataxic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rare human variant of mad cow disease. It is possible, then, that Balanchine died of his virility treatments, though by that time he was pushing eighty and had enough other ailments to have killed him long before.

Homans, I think, was right to be forthcoming about these people’s sex lives. It makes them seem more tender, more likable. Here is a poem that Balanchine apparently wrote to Farrell around this time. He imagines her as a lazy Susan:

Oh you suzi, my la-zy Suzi Com[e] on turn your dish for me, don’t be choosy you lazy Suzi twist and turn for all to see. Roll you[r] stuff-in, show your muf-fin, put out light and give me bite! What a pleasure to be at leisure when she stirs my a-ppe-tite.

This is certainly a dirty little poem, and also very funny. It reminds me of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, both Shakespeare’s play and the beautiful ballet that Balanchine based on it, soon assigning Farrell to the role of Titania. “Lord, what fools these mortals be!” says Puck. Homans sometimes defends Farrell and Balanchine, and goes in for some heavy Tristan-and-Isolde kind of talk about their meeting their destiny: “Between them, there was no clear right or wrong, no should or shouldn’t—they were past all that.” At other times, though, she paints them, with a fine-point, acerbic wit, as the company must have seen them. By the mid-Sixties, she says, Farrell

was taking her rehearsal breaks in Balanchine’s private office and could be seen lounging on the couch in her robe, conferring with him on casting or bent over a crossword puzzle as he caressed her leg.

Balanchine had been the dancers’ god. “Who would ever have believed that we could lose respect for Balanchine?” one of the dancers, Carolyn George, said. “But we did.”

And what about respect for Farrell? In the “Farrell years”—that is, the years of Balanchine’s infatuation with her, roughly 1963 to 1969—he made some of the least interesting ballets of his career. During this period she danced with immense authority and freedom—perhaps too much freedom. The great and craze-resistant dance critic Arlene Croce wrote that Farrell, at this point, had a tendency to throw herself around. Balanchine was right to be in love with Farrell. The audience was right to be in love with her, too. But most of the roles in which she had her greatest triumphs at this time had been made for other women. It was as if she had been sent by God to complete them.

When, after Balanchine and Farrell’s separation, she returned, he at last made, specifically for her, roles that drew on her greatest gifts, in Chaconne (1976), Vienna Waltzes (1977), Walpurgisnacht Ballet (1975), Robert Schumann’s “Davidsbündlertänze” (1980), and Mozartiana (1981), his last top-drawer ballet. Homans writes that “he had to be in love” in order to create, and then she says that when he was most in love—with Zorina, then Farrell—he made weak work. She is at a loss to explain this, but I think that anyone would be. We could say that Puck was right—love makes fools of us all—and then, if we’re lucky, the passion subsides and we regain our sanity. But this seems a rather feeble explanation in the face of the great puzzle Homans sets up.

Homans stresses again and again the sufferings Balanchine went through (“They just left me there…like you take a dog and leave it”) and the courage with which he met setbacks and recovered, recovered, every time—from Zorina, from Farrell, and I have barely mentioned the other girls. But forget the girls. What about the ballets, so deeply thought and felt? To cite just one small example—it should stand for many—The Four Temperaments (1946), a peerless work of twentieth-century modernism, was postponed, put on hold, canceled, and so forth for six years before he was able to get it onto a stage. He stood by it. It has since been performed by scores of companies. This kind of steadfastness, however much it is a moral, not an aesthetic, quality, is a great part of what makes him an art hero. Homans, too, has a lot of backbone. “The deed, the act, the gesture, was all,” she writes. “The gesture, but abstracted. Not the story of feelings, but feelings themselves.” She is sober, reflective, factual. She does not cry on the page. We do.

—This is the second of two articles.

-

1

For more on the first part of Balanchine’s life, see Joan Acocella, “From Russia, with Love,” The New York Review, May 25, 2023. ↩

-

2

He was probably right. Readers might want to look at the films of Zorina on YouTube—for example, the excerpts from Swan Lake in I Was an Adventuress. She was a wooden dancer. ↩

-

3

Balanchine worked with Josephine Baker, Katherine Dunham, the Nicholas Brothers, and many other superb Black dancers. He not only choreographed but also directed the 1940 musical Cabin in the Sky, with an all-Black cast. His study of Black dance is a long story and, as is often the case today, much argued over, but I do not think anyone could deny that it was a large part of what made his style of ballet different from the other Euro-American models, and more interesting. ↩

-

4

Some male ballet dancers have since learned to produce extensions as great as women’s, or close. But when they do this, the action has much less punch, because men’s private parts are located not in the territory in question but further to the front. Also, we have been looking at men’s private parts, once again, covered—and also consolidated, packed in (by a so-called dance belt)—since the early twentieth century. ↩