My first glimpse of Colombia was in the summer of 1973. I’d been living in New York City and was on my way to Chile, to a promised scholarship at a university in Santiago. Some New York friends put me in touch with an Orthodox rabbi, an enthusiast of world revolution with a sideline as a purveyor of slightly dodgy plane tickets. Over a long afternoon, the rabbi and I planned an itinerary that, compared to a direct flight from New York to Santiago, would save me some much-needed dollars. Or so I was assured. After a stopover in Miami, I’d fly to the Colombian coastal city of Santa Marta; from there a train would bear me into the gray heights of the capital, Bogotá, where I’d board a third flight.

At the station in Santa Marta I bought a second-class ticket to Bogotá and settled onto a straight-backed wooden bench in an almost empty car. It was sweltering on the coast, and as we plunged ever deeper into the endless green of the tropical savanna the temperature inside the train grew hellish. Exhausted by the long trip, drowsy from the swaying clickety-clack of the slow, slow train, stupefied by the heat, and having lost all count of the sedate succession of stops, I was snoozing with my head against the dirty window when the train pulled into another station. I raised my eyes and made a listless attempt to clean the window with the back of my wrist so I could see its name. It took me a second to process what the letters said: Aracataca.

ARACATACA!

I rubbed the glass again, shouted for the conductor in vain, and ran to the door to try at least to set one foot on the soil of a place whose mythic history was better known to me than that of my family. But the train was already underway. Aracataca! I rubbed the glass once more to get a better view, tried to stick my head out the narrow crack of the top window, and amid these exertions lost my chance to see the town’s dusty streets. We left them behind in a blink.

Body rigid against the torturous seat, jolting between frustration and euphoria, I noticed the air outside the filthy window growing dark and thought a tropical storm was about to thunder down on us. But that wasn’t what was blocking the light. The train was passing through a dense cloud of yellow butterflies, a tempest of fluttering wings. Then they, too, disappeared behind us.

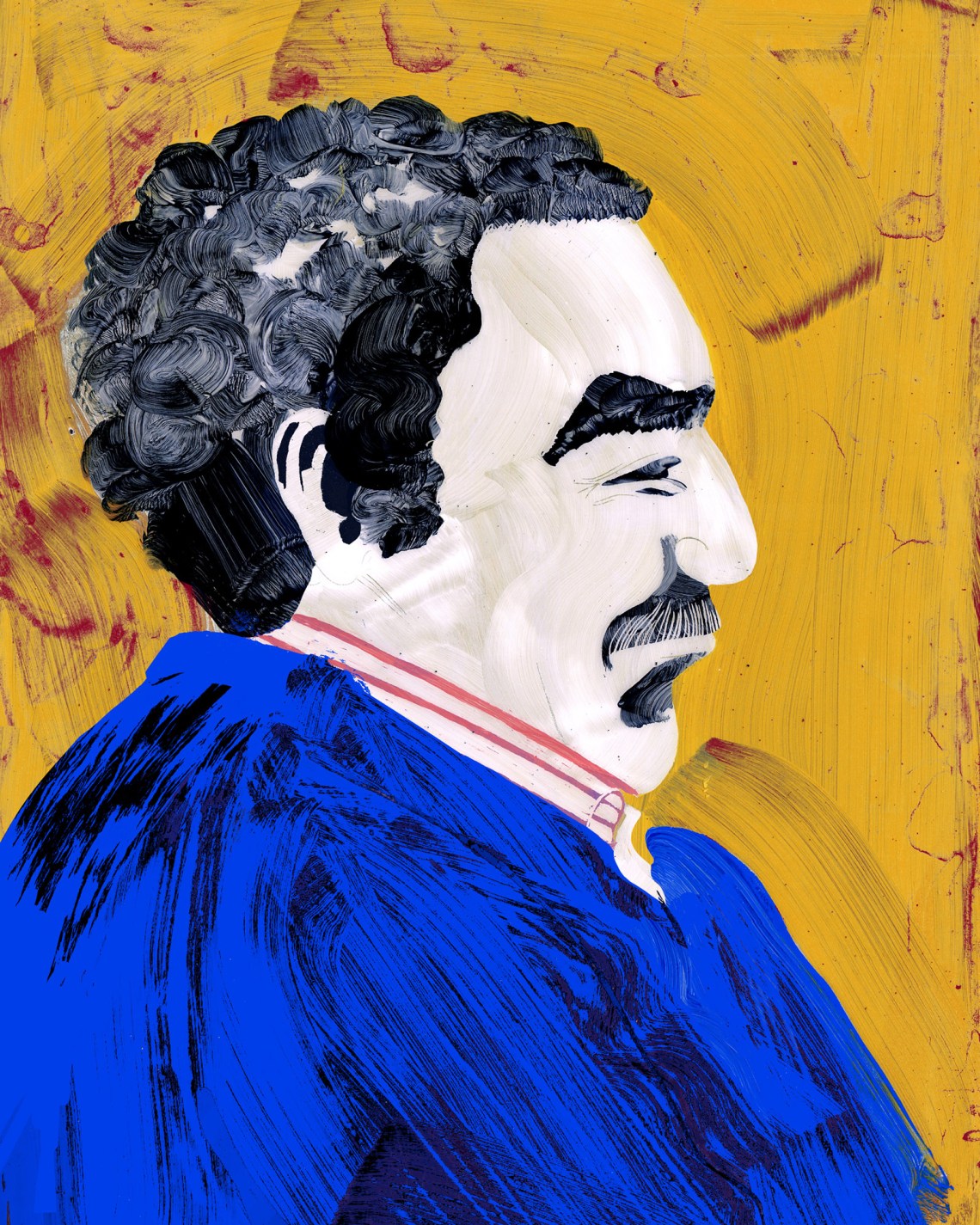

When he heard stories like this, Gabriel García Márquez, in general a terse and circumspect man, would puff out his cheeks, causing the ends of his mustache to lift a little in approval. “No one believes that I’ve never invented anything,” he’d say with satisfaction. “I’m just the scrivener.” And since he was a shy man—another thing no one believed—he would pronounce the last word of the joke with a hesitant intake of breath, then exhale a small cough that didn’t quite agree to be a laugh.

He also declared on numerous occasions that nothing interesting had happened to him after the age of eight. As with many of his pronouncements, this was strictly true, at least in the sense that those first eight years, spent with his maternal grandparents in Aracataca, departamento of Magdalena, Colombia—alias Macondo in his novel One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967)—gave him enough material for the whole of his writing life.

The story of that childhood is well known. García Márquez was born in Aracataca in 1927 and wasn’t quite two years old when his parents’ erratic life obliged them to leave him in his grandparents’ care, while they went in search of better economic prospects that never quite materialized. His grandfather, Nicolás Márquez, had risen to the rank of colonel on the side of the Liberales in the bloody civil conflict known as the Thousand Days’ War, which convulsed the nation as the nineteenth century geared into the twentieth. Grandfather Márquez had a secret: during his military years he had seen combat and dealt death to many, but he had become tormented by the memory of one man he killed after the war over a matter of honor and lived with the burden of this one, lone death as with a ghost.

Hoping to leave the dead man behind, he took his family and abandoned the town where he committed the crime. They lived an itinerant life for a few years, he and Tranquilina Iguarán, his wife, with their two sons and a small daughter, Luisa Santiaga, who would one day become Gabriel’s mother. Accompanying the Márquez family were three “Guajiro Indians…purchased in their own region [of La Guajira, Colombia] for a hundred pesos each after slavery had already been abolished,” García Márquez later wrote. These indios guajiros were to stay with them for the rest of their lives. The family tried to find a foothold in towns and cities around the Ciénaga Grande, a vast, swampy marshland between the Magdalena River and the mountains of Colombia’s Sierra Nevada. At last they fetched up in Aracataca, a banana-growing town in slow decay beneath the tropical heat and biblical deluges.

Advertisement

On one side of the tracks were the United Fruit Company’s immense banana fields, and among them the white settlements with white houses where the white gringos lived a separate life within the barbed-wire fences that encircled their dominions. On the other side was Aracataca, at first no more than a single dusty street with a river at one end and a cemetery at the other. Banana fever hit after the war and with it came la hojarasca—the leaf storm, or rabble, of charlatans, adventurers, fortune hunters, and whores who would one day populate the background of the Buendía family epic, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Following an infamous massacre of striking workers in 1928, United Fruit withdrew from the banana zone of Ciénaga Grande and went on to suspend all operations in the country during World War II. As García Márquez wrote in his memoir, Living to Tell the Tale (2002), the company’s exit brought ruin upon the once-prosperous town. United Fruit took everything with it:

Money, December breezes, the bread knife, thunder at three in the afternoon, the scent of jasmines, love. All that remained were the dusty almendro trees, the reverberating streets, the houses of wood and roofs of rusting tin with their taciturn inhabitants, devastated by memories.

Colonel Márquez, now well established and well along in years, lived in a house with many rooms and wide, shady patios crammed with an assortment of aunts, begonias, sisters, jasmine, mothers, grandmothers, and rocking chairs. The colonel bestowed his love on Gabriel as well as his best stories: about the war, Aracataca’s mythic past, and the vicissitudes of his own life. For her part, grandmother Tranquilina filled the boy’s imagination with detailed accounts of the ghosts and terrors that dwelled in the house alongside the family. Little Gabriel still had a very young child’s stumbling speech when he, too, began telling extravagant, improbable stories. Amid their laughter, his elders scolded him. They hadn’t yet realized that the things he said weren’t lies but “true in another way,” as he wrote in his memoir.

Sitting in a room of the big, shaded house, the boy Gabriel watched as his grandfather, rapt in magical concentration, formed the small, flexible fish made of gold that he sold for a few pesos. The old man took his cherished grandson by the hand and led him to the commissary of the banana plantation to show him ice for the first time. He taught this seven- or eight-year-old child that the gringos, masters of ice and bananas, were responsible for the massacre of striking United Fruit workers mowed down by Colombian troops over the course of a long night in 1928. The colonel also took the boy—but why?—to see the corpse of a friend who had just committed suicide. A murder committed in the name of honor, a massacre, the body of a suicide—young Gabriel’s life was spent in the chaotic happiness of childhood, while his inner landscape filled up with death, fear, and ghosts.

Grandfather Nicolás died just as the family was about to leave Aracataca for good to settle in the small river town of Sucre. With bags packed and departure imminent, the boy saw all his grandfather’s clothing piled in a heap in the courtyard of the old house—his house—and set on fire. Amid the flames, he caught sight of one of his own caps. “Today it seems clear,” he wrote sixty years later. “Something of mine had died with him.”

Thus the great and true story of Macondo, as Gabriel García Márquez narrated it in his memoir. It is true in its own, other fashion, as credible or dubious as any essential memory. The best way to understand it might be not as biography—there is Gerald Martin’s brilliant book for that1—but as a new mythology, constructed out of all the writer’s touchstones.

García Márquez’s exorcism of Aracataca culminated in One Hundred Years of Solitude: the story of the grandfather who’d killed a man and the grandmother who saw ghosts in every corner; of the star-crossed courtship of his father, Gabriel Eligio García, and his mother, Luisa Santiaga Márquez; of the origin of Aracataca and its demise; of his other grandmother, Gabriel Eligio’s mother, an uninhibited woman who has a series of children without troubling herself about marrying any of the fathers and who is nobody’s fool; the banana massacre, the priests, the rain of birds, the discovery of ice. All of it happens in his first eight years and in the modest hundred-odd pages of his memoir that García Márquez devoted to those definitive years and their crucial sequel: the day the twenty-three-year-old would-be writer and celebrated bohemian in the literary circles of the coastal city of Barranquilla went with his mother back to Aracataca to sell his childhood home.

Advertisement

Mother and son traveled by train—that same rickety train—back to the former banana town, now abandoned by United Fruit. They walked among sad ruins, their memories of the town far more real than the moribund reality before their eyes. They endured the blistering heat of the silent, dusty streets. At last they visited the house, crumbling away like a crust of bread left outdoors. The present was spectral; what was most alive was what had died. At the train station with his mother, waiting for the return of the yellow train, García Márquez, too, had become an inconsolable ghost, haunting the rubble of an unrecoverable childhood.

Ghosts are exorcised by writing. His early short stories are just that: an offering to the past made by a talented young man who, like so many other aspiring writers, had spent his time in search of extravagant subjects for ingenious stories that turned out to be incoherent or trivial. After the journey back to his origins, García Márquez was able to abandon that search. Many years later, he was to remember the moment when, confronting loss, he was rescued by the birth of his writer’s gaze: “Nothing had really changed, yet I felt that I wasn’t really looking at the town but…was experiencing it as if I were reading it…and all I had to do was to sit down and copy what was already there.” As soon as he stepped off the train, he rushed back to his desk in the offices of El Heraldo, the Barranquilla newspaper where he was already the star reporter, and drafted the first pages of La hojarasca (Leaf Storm). The next morning, a colleague and friend found him still at his desk, pounding away in a frenzy at the typewriter. “I’m writing the novel of my life,” he announced.

In truth, he was writing the novel of Aracataca, and as he advanced in the telling, he published sections here and there—short stories, novellas such as Leaf Storm (1955), No One Writes to the Colonel (1961), and In Evil Hour (1962). These individual works, fragments of something larger still struggling to be born, are collected in Camino a Macondo: Ficciones 1950–1966.2 In them we meet an elderly good-hearted priest who sees ghosts; another priest, younger and also good-hearted, who mediates disputes that are the smoldering embers of the partisan violence that filled the town with ghosts so many years before; a woman who witnesses, dumbfounded, a torrential downpour that lasts for three entire days. From story to story, certain characters reappear, with distinctive names that make us turn to look, as if we’d chanced upon an old friend at the train station: Nicanor, Rebeca, Remedios, Cote, Moscote, Buendía.

These divergent, only somewhat connected stories take place in a town where the sign in the barbershop always says NO TALKING POLITICS and the mayor always has a toothache. The town has no name, though some stories allude to another town along the same train line: Macondo. (And indeed, in the old banana days, the station between Aracataca and Santa Marta was a somewhat more prosperous town called Macondo.) Some stories take place in a city with a river wharf that could be Sucre, where the García family settled during its eldest son’s teenage years. Other stories happen in a place that has both river and beach, which may be the city of Ciénaga. Subject matter, geography, style, voice: all of it is born at the same time and the stories are, indeed, all part of a single obsessive text. After the Macondo cycle, which begins with “Monologue of Isabel Watching the Rain in Macondo” and culminates, following One Hundred Years of Solitude, with Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), García Márquez wrote other books—about dictators and liberators, enamored young girls, lecherous old men enamored of sleeping young girls—the works of a writer in search of subject matter. The stories collected in Camino a Macondo appeared of their own insistent volition and come on like a locomotive.

It’s hard to know how García Márquez dealt with the fact that one of his novels was a hundred times more famous than the entire body of work that preceded it or came afterward. Perhaps he didn’t know either. On the one hand, he understood that his parents’ love story could well be considered his best novel. On the other, I have no doubt that for him One Hundred Years of Solitude was the pinnacle of his effort to translate reality into literature. What’s more, it made him rich. And famous beyond measure. And something more. I remember, among all the events surrounding his death, the endless line of people who waited more than twenty-four hours to pay him tribute in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, and one man in that line who told a TV news camera that he learned to read so he could read One Hundred Years of Solitude, because his wife, an elementary school teacher, “really liked that book a lot.” I remember feeling regret that the writer was no longer alive to hear this homage, which had nothing to do with fame.

What I’m not clear on is what place García Márquez assigned to the texts in Camino a Macondo. As is the case with every writer, his evaluation of each of his works depended on the day and time he was asked about it. More than a few readers think No One Writes to the Colonel is his most perfect novel, but I have a feeling that he saw that story more as the culmination of a long apprenticeship. It is astonishing that in the one volume of his memoirs he completed, he wrote at length and with youthful enthusiasm of his years as a journalist, culminating in his first trip abroad, when the Bogotá newspaper El Espectador sent him off at age twenty-eight to cover an international conference in Geneva. Then, midstream, he devoted a couple of paragraphs—just two paragraphs!—to the most dazzling event in any author’s life: to the publication of his first novel, Leaf Storm. The reading public has also had some trouble assimilating these first Macondian texts, several of which students at middle and high schools across Latin America unfortunately first encounter as part of the standard curriculum, making them, by definition, boring. Adult readers tend to see them as what García Márquez wrote before One Hundred Years of Solitude.

More than half a century later, it takes some effort to imagine the euphoria generated by the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude—a book that, for readers who came after, has always been there. One long-ago night I sat in the warm glow of a lamp to read a new book someone had just given me, by an author I’d never heard of. I don’t know how time passed on that night—hours that seemed to last both a century and a second—but when I came back to myself, exalted, my head full of a new, teeming world, I looked up and realized I had finished reading by the light of day. One among millions, I treasure the memory of that night as an endless moment of perfect happiness.

No other twentieth-century author proved able to plunge his readers into a complete, magical world with such ease. Or rather: no author who didn’t write children’s literature. One day over lunch, García Márquez announced that he was at last going to start reading J.K. Rowling, “to check out the competition.” The conversation had touched on the matter of royalties, but he wasn’t referring to that; he knew full well that by then the author of the Harry Potter saga had sold millions more books than he had. No: García Márquez understood that he was at risk of being overshadowed by the one other person capable of immersing readers in a world they never wanted to leave.

The immense majority of readers who have sought out No One Writes to the Colonel or Leaf Storm or In Evil Hour have done so after reading One Hundred Years of Solitude—the novel of Melquíades the gypsy and the clouds of yellow butterflies—seeking another fix of the same magic. But the impulse behind the stories in Camino a Macondo is very different. García Márquez would say, “We costeños”—people from the Colombian coast, famous for their party spirit—“are the saddest beings in the world.” In the Macondo epic of these initial stories, sadness, bitterness, and rancor are constants. Hunger is the principal motivator of the action in many of them, and they happen in a place so lost to the world that not even the rich have money. In the masterpiece that is “There Are No Thieves in This Town,” the protagonist sets out to commit a robbery and comes back with three billiard balls.

References to sex are rare and discreet. In fact, it strikes me that just one character—Doctor Giraldo from In Evil Hour—enjoys an active and happy sex life, and we know so because it’s mentioned once, in passing. Meanwhile, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, action often springs from staggering physical desire, and this is most often the case with the female characters, carried away at the sight of men with superhuman penises. Desire is exorbitant, fertile, febrile, creative, and this Macondo is populated with offspring. Children are born right and left, grow, are themselves skewered by desire like butterflies pierced by a pin, and reproduce with even greater fervor.

In the writings gathered in Camino a Macondo, by contrast, even pregnant women are skinny and worn-out; they’ve been with their partners for years and are no longer desired by anyone. Both men and women are locked into the sad loyalty of marriage. Death is present and also, everywhere, rot. A dead cow gets stuck in a riverbank and swells and putrefies over the course of a story, filling the whole town with an unbearable stench. A boy is forced by his mother and grandfather to see the corpse of a hanged man, his protruding tongue half bitten off. Someone imagines in horrifying detail how the flies that descended upon the corpse have been buried with it in the coffin.

There are no flies in One Hundred Years of Solitude. There’s a dead man from whom a scarlet thread trickles, snaking from the room where he lies, flowing down streets, turning corners, entering the Buendía house, and skirting the dining room table to reach a woman who sees the blood and understands that her oldest son has just been murdered. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, in other words, there is a mythology. Complete and circular, like every mythology, it exists in a remote, rewinding time, far from death’s putrefaction. Even the newborn devoured by ants at the end of the novel is an abstraction, a dry husk that never comes to life on the page. Absorbed in reading the predictions of Melquíades the gypsy, the last Aureliano discovers in the novel’s final paragraph that Melquíades “had not put events in the order of man’s conventional time, but had concentrated a century of daily episodes in such a way that they coexisted in one instant.” Aureliano discovers what his creator wants to reveal to us on this last page: his explicit intention to create a family epic within the circular time of myth.

It’s true that everything García Márquez wrote to drain from his heart the venom of the real Aracataca—aka Macondo—was an effort to find his way toward One Hundred Years of Solitude. But it’s also true that Leaf Storm, In Evil Hour, No One Writes to the Colonel, and the short stories collected in Camino a Macondo exist in the harsh linear time of reality and are inhabited by men and women like us, whose destinies fill us with compassion and horror. One Hundred Years of Solitude, one of the most seductive books ever written, fills us instead with astonishment and gratitude. In that sense, these earlier texts are not the road to that novel’s Macondo but constitute a separate Macondo of their own.

“I never forget who I am,” García Márquez would say. “I am the son of the telegraph operator of Aracataca.” It was his journey as a young man back to the home of his childhood that grabbed him by the nape of the neck and forced him to observe himself in the mirror of those deeper waters. There young Gabriel discovered himself to be his grandfather’s son, a child with big eyes opened very wide, who grew up immersed in violence, bitterness, shattering loss, and asphyxiating circumstance. The stories that emerged from that journey are sober and urgent, not mythic but tragic, and propelled by a feverish will to exorcism. They reveal a real past that still wounds. They are magnificent.