Early on a wet spring morning in 1952, Arthur Miller maneuvered his green Studebaker into Elia Kazan’s Connecticut driveway. The ignition off, he sat for a few minutes quietly, battling a sense of dread. Kazan had phoned several times to arrange the meeting. He and Miller were neighbors in the country and best friends; they shared upbringings, tastes, and convictions. In five years they seemed together to have reconfigured the American theatrical landscape. Their collaborations on All My Sons and Death of a Salesman had secured two Tonys for Kazan and a Pulitzer for Miller, who believed his friend possessed of a genius shared by no other director.

Miller suspected that he knew the reason for his summons. In the mid-1930s, Kazan had briefly been a member of the Communist Party. When subpoenaed months earlier by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, he had refused to identify his fellow travelers. He had since found himself frozen out of Hollywood offices, warned that he would never again work in film. Miller presumed that Kazan had resolved to name names, a decision Miller thought disastrous, as he told him when finally the two headed out for a walk that dim April morning. Kazan explained that he had no alternative. Were he to fail to come clean, his artistic life in America was finished. He would be denied a passport to work abroad. Neither for his own sake nor that of his children could he afford to be blacklisted. Someone else would mention the same insignificant names even if he did not. He had moreover no sympathy for communism. Why, then, should he withhold his testimony?

Gently Miller made clear that he thought Kazan naive. He was about to humiliate himself and sacrifice others to a band of cynical fanatics who comported themselves like mobsters but lacked the moral code even of that trade. The panic would subside, Miller insisted. He had not held his friend’s earlier, private HUAC testimony against him. It was consistent with his integrity. But Kazan acted now from fear rather than conviction. He was morally in the wrong. Miller felt, as he put it decades later, “a quiet calamity opening before me in the woods.” He elected not to mention something of which Kazan was unaware at the time: though never a party member, Miller too had attended meetings. He had applied for a “study course” in Marxism.1 Inside his disapproval was a kernel of fear. He could imagine himself among Kazan’s victims. The two walked back to the house in silence.

The conversation lasted less than an hour. As Miller climbed back into the Studebaker, Kazan’s wife, Molly, came out to say good-bye. She seemed to have gathered the walk had not been a success. Did Miller grasp how deeply Communists had penetrated unions? Did he even understand his country any longer, she demanded, motioning down the Connecticut road? Their entire neighborhood supported HUAC and its work. Unable to so much as make eye contact, Miller found himself muttering his way through his side of the conversation. The awkward moment grew fraught when Molly asked if he was heading to his country home. Miller was, he explained, driving to Salem, Massachusetts.

“You’re not going to equate witches with this!” Molly gasped. Leaning through the Studebaker window, she reminded Miller that there had been no witches. There were undeniably Communists. He had yet to decide anything, Miller assured her. He had for some time resisted writing about Salem, unconvinced he could manage to wrap his mind around such preposterousness. He did intend at least to make an exploratory trip to the archive, however. Grimly, under a steady rain, they waved good-bye. Miller headed north to research what became The Crucible. A week later Kazan headed south to name names in Washington.

Salem was, for Miller, full of surprises. He found that an industrial town had supplanted the wooden village of his imagination. It had not yet acquired its carnivalesque atmosphere; it would be several decades before Salem appointed itself “the Witch City” or stitched flying broomsticks on its police uniforms. In 1952 no one spoke freely of the events of 260 years earlier. Miller was taken aback not only by the silence about the witchcraft epidemic—“You couldn’t get anyone to say anything about it,” he observed—but by how much, even under a cold drizzle, he took to “morose and secret” Salem. As he left the archive one day, he found himself transfixed by an etching on the Essex County courthouse wall. He understood it to be the work of a 1692 eyewitness. As he recalled:

A shaft of sepulchral light shoots down from a window high up in a vaulted room, falling upon the head of a judge whose face is blanched white, his long white beard hanging to his waist, arms raised in defensive horror as beneath him the covey of afflicted girls screams and claws at invisible tormentors. Dark and almost indistinguishable figures huddle on the periphery of the picture, but a few men can be made out, bearded like the judge, and shrinking back in pious outrage.

It is an image that does not exist, but no matter.2 It worked its magic. Miller recognized the judges’ moral intensity, their defensive spiritual crouch. The skullcaps and dark robes transported him back to the Harlem synagogue of his childhood. God was, he reasoned, driving these “putative ur-Hebrews” as crazy as he had driven the Jews.

Advertisement

The crux of the play came to him on his second afternoon in Salem, when Miller read the account in the trial papers of forty-one-year-old Elizabeth Proctor’s hearing. In the 1692 meetinghouse, Abigail Williams, one of the first afflicted girls, fell into fits before the authorities. She thrust her hand into her mouth. She fell dumb. She convulsed. She swore she could see Elizabeth Proctor—visible to everyone else at the front of the room—balanced on a beam above. She implicated Elizabeth in a blood-drinking satanic feast. “Dear child, it is not so,” Elizabeth objected, evoking fresh paroxysms. John Proctor evidently rose to defend his wife. Mid-examination, Abigail pronounced him a wizard.

In the course of the testimony, she reached out to strike Elizabeth, a gesture that Abigail’s uncle, the village minister, described in minute detail. As she extended her arm, her fist unclenched. She managed only to brush Elizabeth’s hood with her fingertips when she howled in pain. Her hand, she cried, was burned! Another afflicted girl crumpled to the floor in what would prove one of the most dramatic, and chaotic, of the witchcraft hearings. As a nineteenth-century chronicler remarked, in pages that Miller read in 1952, there had seldom been better acting on the boards of any theater: “No one seems to have dreamed that their actings and sufferings could have been the result of cunning or imposture.”

Into the repelled fist Miller read something no one had read before or would again. He surmised that Abigail had insinuated herself into the troubled Proctor marriage. The frustrated assailant was determined to drive Elizabeth from town so that she might claim John, “whom I deduced she had slept with while she was their house servant, before Elizabeth fired her,” Miller wrote later. With her singed fingertips, Abigail handed him his play.

The real Abigail Williams was eleven years old when she accused Elizabeth Proctor of witchcraft. She had never lived with or worked for Elizabeth Proctor, whose real servant never named her. Abigail Williams may or may not even have known Elizabeth Proctor. Miller had nonetheless precisely what he needed: a motive for someone to sow holy terror, to sacrifice another, to sully an unblemished reputation with what would, at another time, have seemed a ludicrous charge. The girls launched what Miller later termed “hallucinatory spitballs.” Here was an illustration of how we cleanse our consciences by projecting our misdeeds onto others, here was a world upended by its own sacred beliefs, an almost indigestibly rich banquet of human psychology—in Miller’s eyes, “a veritable Bible of events.”

So buried had he been inside the Salem delusion that Miller was startled, on his drive home a week later, by the six o’clock news. Over the car radio he heard about Kazan’s April 10 appearance before HUAC. Wincing for and ultimately furious with Kazan, he drove slowly, worrying that at any moment he risked “skidding into oblivion.” He was still uncertain about the theme of his play, but by the time he got out of his car in Brooklyn he knew he had committed to writing it.

Later that week he opened a letter from Molly Kazan. Described by her husband, with admiration, as “scrupulous and ornery,” Molly freely spoke her mind. Again she argued against the Salem idea. With his rickety parallel, Miller would, she insisted, sidestep the larger question of what caused a panic in the first place.3 She played on his feelings of disassociation. Miller had complained for some time that he felt out of touch with the country, removed from the mainstream. He risked producing a work that would disappear with the headlines. Did he really mean to stake his reputation on the assertion that suspicions about Communists were unfounded, the panic wholly invented?

Indeed, Miller assured Molly Kazan in a lengthy reply, Communists existed and witches did not. But the paranoid leap into fantasy was identical, as was the rampaging fear at the center of both crises. HUAC’s aim, he wrote, seemed to be “to throw perfectly honest people into a kind of nameless fear which is utterly destructive of a sane order of life.” Did Molly really mean to support the work of men who promoted “the inherent violence of super-patriotism”? He knew she did not believe this was a panic that left people stabbing at shadows, but did not know how else to make sense of shameless ideologues who caused good men to betray themselves. He confessed to “a profound and weeping interest” in the subject. To Kazan’s behavior Miller contrasted that of saintly, seventy-one-year-old Rebecca Nurse, the Salem great-grandmother who in 1692, on trial for her life, held her ground, refusing to utter the lie that dishonorable men demanded of her.

Advertisement

Behind every moral panic, Miller believed, stood an evil impresario, eager for his own reasons to manipulate the raw materials. When it came to making sense of Salem, he would implicate Samuel Parris, the minister who—as Abigail Williams convulsed in his home—churned adolescent afflictions into the original plot against America. Miller captured the epidemic’s hysteria but indicted the wrong impresario. He ignored Thomas Putnam, the villager whose feet stick out most conspicuously from behind the Salem curtain and whose twelve-year-old daughter named sixty-two names, accusing dozens of adults she had never met, in some cases of crimes committed before she was born.

The committee thanked Kazan for his help unmasking a plot against America. Accounts of the testimony exploded in the papers. Kazan fielded anonymous phone calls, vitriolic letters, and death threats. His secretary quit. He hired a bodyguard for his family. To his surprise, he heard nothing from his former best friend. When next Kazan and Miller crossed paths, in the lobby of Kazan’s office building, Miller pretended not to see him, a snub Kazan never forgot.

From the start Miller knew where the new work opened: a séance with Tituba, the Indian slave in the Parris household, originally prefaced Abigail’s attempt to seduce John Proctor. There was precedent for opening a tragedy with a supernatural assembly in the wilderness. And Miller was not the first to attempt to fold the witch trials into a play. Longfellow had beaten him to it by eighty-five years. He too had opened Giles Corey of the Salem Farms with wonder-working Tituba, who announces, of ministers and magistrates, that “while they call me slave, are slaves to me!”4

Miller headed next for Abigail’s collision with Proctor, to the moment when “Proctor, quietly, decides to ‘clear up’ things and confess his sin with Abigail—to show that this is her guilt, her reason for acting. She then must accuse him,” leaving him to grapple his way toward the decision that his life means less to him than does false testimony. Miller added four years to Abigail’s age—he later affixed two more—and deducted three decades from Proctor’s, to facilitate the relationship.

Miller would say that he thrilled to the sensuousness of the early American prose, with “its swings from an almost legalistic precision to a wonderful metaphoric richness.” He relaxed almost immediately into its dense, gnarled syllables. Contemporary diction seemed ill-equipped to accommodate the strains and stresses of the story; he attempted to sculpt an entirely new language, groping about for one that felt archaic yet flowed naturally, drafting most of the play in verse. At some point in 1952 he enlisted the poet Kimon Friar, then teaching at NYU, earlier the tutor and lover of James Merrill, for syntactical assistance. He worked his way steadily through the forest of material, copying out bits of testimony, fixing on plot points, drafting snatches of dialogue, trying to locate the fault lines, to connect a society in crisis with the logic behind that crisis. He collapsed individuals into each other. He discarded and invented others, permanently transforming a number of Salem afterlives. No one shape-shifted quite as dramatically as Tituba, Indian in the court papers, Black and versed in voodoo by the time Miller had finished with her.5 Miller invented the naked frolic in the woods, nearly impossible afterward to peel from the history.

What he thought of the finger-pointing girls leaks out in his stage directions. Abigail has “an endless capacity for dissembling.” Mary Warren is “subservient, naive, lonely.” A fictional composite, Susanna Walcott is a “nervous, hurried girl.” Mercy Lewis, twice a refugee from the Indian wars and the source of some of the most kaleidoscopic witchcraft testimony, is “a fat, sly, merciless girl of eighteen.”

Innocence, Miller seemed to suggest, had long since departed the scene. Eleven in 1692, seventeen in 1952, Abigail was, in his rendering, “strikingly beautiful.” (The record allows only that she was blonde.) It says something that Miller convinced himself that Abigail—the ringleader in his version alone—wound up a prostitute in Boston, for which there is no evidence. About sexual tensions he may have had a point. There is plenty of piercing and pecking and pricking in the witchcraft testimony, as there were plenty of knees soldered together and chests thrust skyward. But there is no evidence of sexual assault.

Ultimately Miller inserted long expository passages into the play. Gristle in the soup, the bane of any high schooler, they sound suspiciously like the historical record. Here Miller performs true magic, stating in a preface that The Crucible should not pass for history while stipulating—the authentic masquerading as the true—that all his characters reprise their nonfictional roles.

More of a vixen in the notebooks than she would appear onstage, Abigail told John in one discarded passage that “there never were a husband didn’t linger at my bed to say goodnight.” Originally she could be seen loosening her clothes and dancing suggestively in the woods. “My skin howls at every passing breeze/I never sleep but dreams come itching/Up my back like little cats/With silky tails!” she cries. She is embracing a tree when Proctor happens upon her. “Why aren’t you in bed?” he asks. “There’s no one to keep me there,” Abigail purrs. She knows her power. “Had I a ship for every holy hand that tried to lift my skirt,” she tells Proctor at one point, “I’d own a fleet to sweep the seven seas and make me queen of the world.”

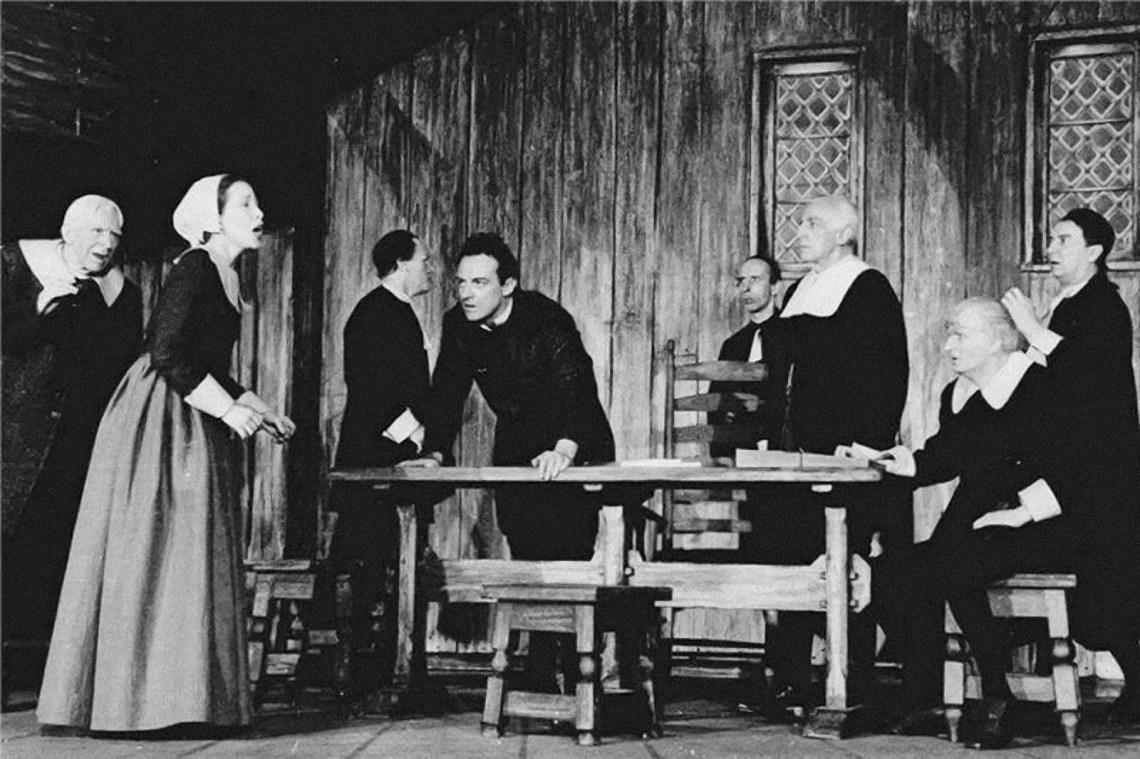

Titles did not come easily to Miller, which is a way of saying they came too easily. A View from the Bridge was originally “The Men from Under the Sea.” Death of a Salesman had been “The Inside of His Head.” He toyed with at least eighteen alternatives for the new play. (His wife, Mary, suggested Death of a Salem.) Along the way he discarded The Devil’s Rendezvous and That Invisible World in favor of The Familiar Spirits. Weeks before the 1953 opening he settled finally on The Crucible, a title that appealed partly because no one seemed to know what it meant. When it came to directors, his first choice was the last person he could ask. Jed Harris was brought in, with disastrous results that manic, multiple, premiere-delaying requests for rewrites might have foretold. A calamitous dress rehearsal followed. Too late, Miller remembered the old wisdom that no one had ever managed a hit in Puritan dress.

The Crucible opened on Broadway on January 22, 1953. Expectations ran high; it had been four years since Death of a Salesman had met with near-universal acclaim. Few understood the title and even fewer seemed to appreciate the play, staged with all the dynamism, its author acknowledged, of a Dutch painting. From the back of the theater he watched in horror as the audience fell asleep. It seemed to Miller as if “an invisible sheet of ice formed over their heads, thick enough to skate on.” Friends of long standing breezed past him after the curtain went down.

In the Times Brooks Atkinson deemed The Crucible blunt, crude, inert, and overstuffed. To George Jean Nathan it registered as “an honorable sermon.” It was dismissed as melodrama and a history lesson, more an outburst than a play, neither art nor entertainment, as mechanical, medicinal, didactic, hermetic, clumsy, creaky, icy, turgid, empty, and labored—some of which remains true. The cast was playing for reduced pay when, on the night of June 19, 1953, the audience rose not to applaud but to stand, heads bowed, in silence. Whispers finally reached the stage: the Rosenbergs were that evening executed at Sing Sing. Afterward The Crucible became, at least for the cast, at least as Miller saw it, “an act of resistance.”

He was correct about the sheet of ice. He had written a cold play about a bleak place in which a woman under duress apologizes, after a chilling course of events, for her frozen heart. Critics felt, as Miller put it, “refrigerated by the social climate at that moment.” He attempted to salvage the operation with a pared-down production, extending the initial run for several weeks. Though it won him a Tony, The Crucible proved a disappointment. Often in lofty terms, he returned over and over to the question of why he had written it, embracing and disassociating himself from the topical analogy; the play had opened when even Le Monde dubbed Senator McCarthy “the maniac of the witch hunt.” The Crucible had in no way been all about red scares, Miller insisted in 1958. It was about the conflict between a man’s idea of himself and what happens when he outsources his conscience, an explanation that might suggest it was largely a play about Kazan.

It would be some time before The Crucible escaped the midday sun of McCarthyism, allowing its audience to sink into the cushioned comfort of allegory. It would be years, too, before Miller spoke about the nonallegorical anguish at the center of the play; there was good reason why Abigail’s fist might land with such otherworldly force. Again Miller had Kazan to thank for the gift, if a gift it truly was. Even before the walk in the Connecticut woods, well before he had convinced himself he would not be writing his way into a wilderness, long before Miller had resolved the play’s technical problems, the story had come into focus. He had in mind the image of John Proctor, the Salem farmer who—having slept with his servant—watches in horror as she accuses the wife he has himself betrayed.

In part he had the colossal success of Death of a Salesman to blame. As Kazan saw it, that work had transformed its author into the unlikeliest of breeds: the swashbuckling public intellectual. Suddenly Miller was dining with Thomas Mann and affecting a pipe. His very carriage changed. The celebrity went to his head, and inevitably the celebrity went to Hollywood, where in January 1951, between takes on the Twentieth Century Fox lot, Kazan introduced him to a contract player with a bit part in a comedy. It may not have been the most innocent of introductions; Kazan knew the Miller marriage to be strained, his friend starved for sexual release. (Miller’s early assessment of the marriage: “She demands nothing and yet gives everything—paradise.” Mary Miller’s assessment, years later: her husband always needed to hear that he was the greatest writer since Shakespeare.) The contract player was twenty-four but looked younger. As Miller shook her hand a bolt of electricity shot through his body. The actress, with whom Kazan began an affair days later, was Marilyn Monroe.

Kazan threw Miller and Monroe together at a party later that week, noting, as the two danced, “the lovely light of lechery” in Miller’s eyes. Marilyn positively glowed. She seemed under the impression that she had met Abraham Lincoln. “I did the decent thing,” Kazan reported later, “said I was awfully tired, and would Art take her home.” In a talk with Monroe that lasted into the morning, Miller elaborated on his threadbare marriage. He was smitten, or as Kazan phrased it, “in trouble, the kind of trouble we should all be in once or twice or three times in our lives.”

Miller realized as much and abruptly changed his Los Angeles departure date; at the airport, where she saw him off, he watched as the lounge watched Monroe. Four decades later he could still remember the beige skirt and the satin blouse she had worn that day. In a different kind of panic, he flew east. “I knew,” he wrote later, “my innocence was technical merely,” a knowledge that profoundly shook the father of two. He had escaped destruction. He regretted having escaped destruction. In Hollywood Kazan spent the next months looking into the eyes of his best friend on Monroe’s Hollywood bedside table. She built a shrine around his photograph.

The state of the Miller marriage did not improve when, on his return, he confessed to his near lapse. There had been a brief, earlier temptation, one that had sent both Millers into analysis. Mary, Miller’s first girlfriend and his wife of eleven years, seems to have been disinclined to forgive. The project for which he had flown to California came apart, but the spell refused to lift. Though Miller and Monroe exchanged only occasional notes over the next years, she had colonized his imagination. He thought of her day and night. It was in this technically innocent open parenthesis that Miller wrote The Crucible, dedicating his own haunted history to Mary, hardly the first instance of a man attempting to write his way back into his marriage.

When asked later about Abigail and Proctor’s liaison, Miller replied that he had included it for two reasons. In the first place, he believed they had truly had a relationship. Only much later did he add that trouble at home had played a role. “My own marriage of twelve years was teetering and I knew more than I wished to know about where the blame lay,” Miller wrote in 1996. That Proctor’s strangling guilt might make of him the voice of reason reassured Miller. He was in the market for redemption: even a tarnished soul might deliver the sterling lines. With a few decades’ distance Miller emphasized the personal calvary over the McCarthy analogy. Some recognized the first from the start. Kazan read The Crucible as a public apology to Mary. “I had to guess that Art was publicly apologizing to his wife for what he’d done,” he observed. From the outset, the betrayal in the play struck him as more sexual than social, an observation largely submerged today. In a quip that Miller put down to professional jealousy, Clifford Odets dismissed The Crucible as “just a story about a bad marriage.”

Despite the lukewarm Broadway reception and without its American baggage, The Crucible traveled comfortably throughout Europe. Salem witchcraft struck a particular chord with the play’s Belgian director, who thought back to the dark days of the Spanish Inquisition. He hoped that Miller might attend the March 1954 Brussels premiere. Only after he had accepted the invitation did Miller discover that his passport had expired. The State Department elected not to renew it, refunding Miller’s nine-dollar application fee and issuing a press release declaring his presence abroad antithetical to US interests.

Miller issued a statement of his own. While he did not support communism, he did consider himself something of an expert on witch hunts. And he knew that in the face of delusion, truth could expect to come in for a beating until the hysteria had passed, by which time there was plenty of shame and discomfort to go around. He hoped that the State Department would excuse him if—despite its vigorous campaign to cast him as a subversive—he did “not fall into a cold sweat or dead faint.” With his plays he wagered that he had made more European friends for American culture than had the State Department, which, he added, was not difficult. Certainly he had made fewer enemies. It was easier to sound flippant given prior brushes with the government. All My Sons had earlier been removed from the army’s repertoire, deemed bad for morale. Salesman too had been censored. Still, there was a familiar surreality to the next years. Miller felt as if he were up against the Duchess from Alice in Wonderland.

As he would again later, he compared himself to John Proctor, a bluff farmer of good nature and high spirits. Proctor did not shy from expressing skepticism about the village girls’ fantastical claims, likely the reason he was accused of witchcraft in the first place. Miller may or may not have known that Proctor too had drafted a petition, on the Salem prison floor, shackles dangling from both wrists. Indeed men had confessed to witchcraft, he informed the court. He had interviewed every one of them. They had fabricated their accounts, in some cases because they had been tortured. Meanwhile a terrible miscarriage of justice loomed. Proctor spoke not for himself but for his fellow prisoners, for whom he demanded only a fair trial. He pointed out something the witchcraft court seemed not to have noticed: in their headlong prosecution, those men had begun to resemble the villains they claimed they meant to eradicate.

Three years after the conversation in the Kazan driveway, Miller finally succumbed to the temptation of Marilyn Monroe. In that time his marriage had essentially imploded. Also by 1955 Monroe had become a platinum blonde and a star. She was Playboy’s first “Sweetheart of the Month.” She had also become Mrs. Joe DiMaggio, which did not prevent her from announcing that she intended to marry Arthur Miller. He held out as long as he could, then fell, hook, line, and sinker, meeting Monroe in stolen moments, introducing her to a few intimates, ultimately moving out of the family brownstone. To a Time reporter Miller explained of Monroe, “She’s kind of a lodestone that draws out of the male animal his essential qualities.” From a commercial point of view, observed Norman Mailer, the romance generated an excitement roughly equivalent to five new Tennessee Williams plays. In the spring of 1956 Miller was ready to file for divorce and preparing for his obligatory six weeks in Reno.6

Also by the spring of l956, HUAC found the nation’s attention to have drifted. The committee’s work no longer generated headlines. Miller himself had disengaged politically. He was on the Nevada divorce mission when, with a light tap to his lapel, a government investigator served him with a pink subpoena. (Out of curiosity, Miller joined the investigator for a cup of coffee. They discussed Lee Cobb and Salesman, though Miller could see that his new friend meant primarily to size him up. When he appeared before the committee, would Miller comport himself as “pussycat or rattler”?)

“Miller assumed he owed the summons to the headline-generating romance with Monroe, guaranteed to return HUAC to the front page. Inadvertently the committee also accelerated the Miller/Monroe marriage. Testimony, on June 21, 1956, veered swiftly offtrack: while HUAC’s counsel meant to discuss The Crucible, Miller talked instead of his passport travails. Monroe heard him say on national television that he needed the document to travel to London. He intended to make that trip “with the woman who will then be my wife,” words that nearly toppled Monroe, with whom plans had been vague. Unlike most of the celebrities who had appeared before HUAC, Miller refused to name names. His conscience, he reported, channeling John Proctor, would not permit it. He and Monroe married days later. In July the House of Representatives voted 373–9 to indict him for contempt of Congress, for which he received a thirty-day prison term and a fine.

By the time he was convicted, The Crucible had been translated into French and reworked for the screen with a script by Jean-Paul Sartre. Having starred in the stage production, Yves Montand and Simone Signoret reprised their roles in the 1957 Les Sorcières de Salem. It is not a subtle adaptation. “If you want to keep him, learn to caress him,” Abigail at one point instructs Elizabeth Proctor, who accepts full responsibility for the crisis. Her tongue had been tied, her heart sealed, her body numb. “It’s all my fault,” she wails. Miller resigned himself to the film. On the one hand, no American studio would touch The Crucible at the time. On the other, he loathed the script, into which Sartre had ladled a full helping of Marxism.7

When the film was released in America, The Crucible had returned to the New York stage in an off-Broadway production. Miller could feel the 1958 audience warming to the work as the 1953 audience could not. McCarthyism, he again insisted, had been only in part on his mind. The play, he wrote that year, was about crusading fanaticism in its multiple forms, about men who orchestrated reigns of terror so as to seize the levers of power. Convinced of its own persecution, the right suffered a perpetual paranoia, one it pinned, in turns, as he would put it later, on “foreigners, Jews, Catholics, fluoridated water, aliens in space, masturbation, homosexuality, or the Internal Revenue Department.” Some portion of the country labored always under a spell. The opposite of such paranoid politics, Miller observed in 1967, “is Law and good faith.”

Could it all happen again, he wondered aloud, forty-nine years before Democratic Party officials were said to be running a child sex ring out of a Washington, D.C., pizza parlor? Miller believed it could, which was the point. The “global cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles” of which Marjorie Taylor Greene warned sounds eerily like the local cabal of Satan-worshipping Puritans. By the time Miller’s fine and prison sentence were overturned on appeal, in 1958, The Crucible was on its way into the canon, to haunt generations of schoolchildren and to subsume, as neatly as any work of art this side of All the King’s Men ever has, the history on which it is based.

In addition to all else, the play offers something so simple it’s easy to forget it’s there: an explanation for the suffocation of reason and for the actual greatest witch hunt in American history—even if Miller seems to suggest that the “poisoned cloud of paranoid fantasy” blew in because of John Proctor’s libido. As a scholar observed in 1955, “one might fairly infer from the play itself that if Abigail had never lain with Proctor nobody would have been executed.” Generations of us have been force-fed the play, holding its own behind Shakespeare in terms of popularity in high school, where it arguably belongs. If you starred in The Crucible as a student, you’re in good company. So did Gene Wilder. So did Miller’s daughter.

The marriage to Monroe lasted five years, ending only after Marilyn seduced a second John Proctor, making quick work of Yves Montand. It had served neither party well. In its course Miller wrote no new play. Monroe had three breakdowns and three times tried to kill herself. “I thought he was Lincoln, but Lincoln had a great sense of humor,” she told the press. She hovered visibly over much of Miller’s later work.

By the time she filed for divorce, The Crucible was more or less continuously onstage somewhere in the world. Miller would say he could always tell when a dictator had just been deposed or a coup threatened, as a Crucible production reliably followed.

That we should be talking back to The Crucible at a time of what Miller termed “hallucinatory spitballs” and “thuggish self-righteousness” is unsurprising. The unexpected part is who is conjuring with the classic, and how thoroughly those playwrights have turned allegory inside out. The great works of theater, Miller noted, “had all been written by unhappy men;” three twists on Salem appeared onstage last year, all written by women.

For her part, Sarah Ruhl was thunderstruck to discover Monroe lurking at the heart of The Crucible. Generations of schoolchildren had been asked to examine their consciences because Arthur Miller fell for a Hollywood bombshell! Are we really, Ruhl wondered, meant to feel sympathy for a man because he has not had sex in seven months and tells the young woman with whom he works out his frustration to wipe the sin out of her mind?8 There are any number of explanations of mass hysteria, Ruhl has observed, but surely a middle-aged farmer’s fatal attraction to an adolescent should not count among them. For different reasons from Molly Kazan, she finds Miller’s play “fundamentally dishonest.” Playing loose with the facts, it spreads out its voluminous expository blanket, stifling the history.

In Becky Nurse of Salem, Ruhl offers the story of a middle-aged woman who unapologetically enters into an affair with a married man, on whom she casts a store-bought spell. Ruhl’s heroine descends from Rebecca Nurse, whose courage Miller applauded and whose wax avatar greeted the Lincoln Center 2022 audience. A Salem tour guide, Becky is disciplined for her ham-fisted attempts to set the record straight. She retaliates by attempting to liberate her wax ancestor, literally making off with the history—and landing in jail. The delusional forces remain offstage but within earshot: we hear about witch hunts whenever anyone turns on a TV. The history, too, slides about in the background. Ruhl includes a running gag about Gallows Hill, its location obscured for centuries by shame and guilt.9 In retrospect, Miller wished he had had “the temperament to have done an absurd comedy” about 1692. Ruhl’s provisional subtitle was “Lock Her Up, or, A Comedy About a Tragedy.”

John Proctor plays no role in Becky Nurse of Salem, which Ruhl dedicates to the women who hanged and to the girls who have played Abigail in school productions. Still, you know something is in the air when two works turn up within months of each other, one titled The Good John Proctor and the other John Proctor Is the Villain. In the Bedlam Company’s 2022 production of The Good John Proctor, Talene Monahon’s Abigail and Betty, literary descendants of the first girls to manifest inexplicable symptoms, inhabit a sort of cramped, adult-free twilight. It leaves them squinting into the dark for answers. Some are supplied by the cider-chugging, profanity-spouting Mercy Lewis, who ambles in at opportune moments to deliver local gossip and steal the scene. Taking “flat, sly, merciless” to a new level, Monahon describes Mercy in the program notes as “the child alcoholic.”

Fourteen-year-old Mercy can make some sense of that out-of-nowhere, rust-colored blood that startles Abby awake one night. The problem, she explains without entirely explaining, is not when you bleed, but when you don’t. Mercy laments the good old days. She rants about sin and depredation. “There is sin in our porridge!” she warns. She has just walked out on her employer, a former Salem minister, because “he’s not a good man and he was a shit-hack reverend.”

For the most part we are left to infer what Mercy’s fire-and-brimstone pronouncements, witchcraft rumors, the fits of a newly arrived servant girl, and Proctor’s offstage abuse of Abby will add up to once the authorities descend; most of the play serves as a sort of prequel to 1692. (So much for high school productions. In a note on casting, Monahon warns that her characters are not to be played by anyone under the age of eighteen.) At play’s end, Betty and Mercy meet, children in tow, for a 1707 playdate that turns into a postmortem on the trials. “It was painful work, but it was important,” Mercy notes of this early Me Too movement. Sixteen ninety-two was, she swears, “the best year of my life.” She then reveals what we may have suspected all along: she was three years old when that “shit-hack reverend” abused her.

Monahon allows herself only a rare allusion to the fact that her characters may have walked in from someone else’s play; she is rewriting the history rather than The Crucible. Still, we have come a great distance from “the ravings of a klatch of repressed pubescent girls” who, as Miller had it, wage “an implicitly sexual revolt.” (He seemed to have forgotten that they were prepubescent girls until he got his hands on them.) In seventy years the balance of power has shifted. Miller does not get all the credit; a great deal goes to an immensely powerful man who has spent five years whining that he is the victim of “the greatest witch hunt in American history.”

Miller never got over The Crucible’s disastrous opening, never forgot the glacial chill in the theater or the snubs in the Martin Beck lobby. He watched dotingly as his problem child grew up to become his most popular play. He could sound like a bit of a blowhard on its account. He was prouder of The Crucible than of anything else he had written. It had handsomely answered its critics. It had long survived McCarthy.

Miller explained in any number of ways his reasons for writing it. He had hoped to wake a country that had drifted asleep when democracy stood in peril. He had been struggling for sanity. In the thick of an ideological war, America had drifted into the hands of “a ministry of free-floating apprehension.” He could bear his friends’ moral paralysis no better than he could “the spectacle of intelligent people giving themselves over to a rapture of murderous credulity.” He had seethed through the McCarthy circus, when it seemed that just about anything that escaped the senator’s mouth, “no matter how outrageously and obviously idiotic, could be made to land in an audience and stir people’s terrors.” He came to understand the deep pleasure to be found in jumping from logical bridges, the willful weaponization of untruths, the love of delusion. By comparison, he observed, “the search for evidence is a deadly bore.”

In his late eighties he told an interviewer that the lines he heard prosecutors speak at the 1949–1950 hearings sounded precisely like what he had read of Salem: “At first it was simply unbelievable, but I went back into history and there it was. It was mind-boggling that the same material could have arisen some three hundred years later.” It remains mind-boggling today that pillars of society chose to handcuff themselves to delusion. “And we know not who can think himself safe,” a group of Essex County farmers yelped late in 1692, wondering, in a petition submitted to the Boston authorities, if those who pointed fingers were not themselves the diabolical ones. Miller at one point affixed a warning to his play: “And when the government goes into the business of destroying trust, it goes into the business of destroying itself.”

By no means a subtle piece of work, The Crucible has at once survived and anticipated the headlines. Politics supply its muscle and sinew. But its beating heart is the predicament Miller lent John Proctor, both of them contending with a different order of invisible world. Whether it slips past us or not, the molten Monroe center has kept the play vital and—in ways Miller never imagined—unsettling. Creaky, sententious, sophistic, indigestible though it may feel, The Crucible promises to remain with us in one form or another so long as “hallucinatory spitballs” fly. “I’m not really a moralist,” Arthur Miller wrote in his last decade. “I just make the assumption that certain things we do lead to catastrophe.”

-

1

Kazan remembered the conversation differently but agreed that the two had never leveled with each other about their Communist pasts. One did not ask such questions at the time. ↩

-

2

Miller likely misremembered Joseph E. Baker’s 1892 engraving in which gleaming thunderbolts shoot down upon an accused witch. Before the court, she is bathed in a powerful, otherworldly glow, light that has released her outflung arms from a set of shackles. The judges and accusing girls recoil from her power. Her chains, sailing across the room, are on course to hit the startled court reporter in the eye. ↩

-

3

Miller was not the first to the analogy. Edmund Morgan remarked on the parallel as early as April 1950, in reviewing the narrative history of Salem that had caught Miller’s attention as an undergraduate. ↩

-

4

Longfellow’s Giles Corey of the Salem Farms followed at least two other nineteenth-century works: James Nelson Baker’s 1824 Superstition and Cornelius Mathews’s Witchcraft or the Martyrs of Salem. In 1893 Mary E. Wilkins Freeman added Giles Corey, Yeoman to the mix. ↩

-

5

Only one publication noticed he had made the sole Black member of the cast sound like “an Aunt Jemima type.” That was the Daily Worker. ↩

-

6

In one of the more entertaining literary letters of the decade, the playwright above whom a sort of moral halo had coalesced applied to a friend, in strict confidence, for travel advice. Miller had a ticklish problem. He anticipated that he would need on occasion to entertain a Nevada visitor who, though dear to him, was also “unfortunately recognizable by approximately a hundred million people, give or take three or four.” A master of disguise, she could affect a limp or bury herself in a coat. But might there be such a thing as a discreet bungalow, far from all crowds? Miller’s correspondent—and for some time his Reno next-door neighbor, in town on the same errand—was Saul Bellow. ↩

-

7

The irony that Montand and Signoret were Communists—and met that year for a five-hour talk with Khrushchev in Moscow—went unnoticed. ↩

-

8

It was worse in Miller’s notebook. “They imagine lechery and then are as certain of it than if it happened,” Frances Nurse muses, commiserating with Proctor about the girls’ allegations. ↩

-

9

It’s either, her characters variously insist, above Walgreen’s, or near Dunkin’. Smart money is on the former. ↩