The door of his dressing room opened and I was about to say something to Leonard Bernstein, though I had no idea what. I was fourteen years old, a nervy kid from the sticks with embarrassing eyeglasses, but Bernstein’s smile, as he inched his way through the assembled crowd, radiated reassurance. Next thing I knew I was gripped inside a Lenny hug and a question began formulating in my mind, as if he was squeezing it out of me. I loved the record he’d made in 1976 of the jazz-powered ballet La Création du monde and found myself asking him about its composer: “Do you still perform Darius Milhaud?” Bernstein gazed deep into my eyes, raised his hand toward his mouth as he corrected my pronunciation of Milhaud’s name, and asked, “You like M. Milhaud’s music?” I nodded enthusiastically. Then a grin and a compliment: “You’ve got great taste, kid.”

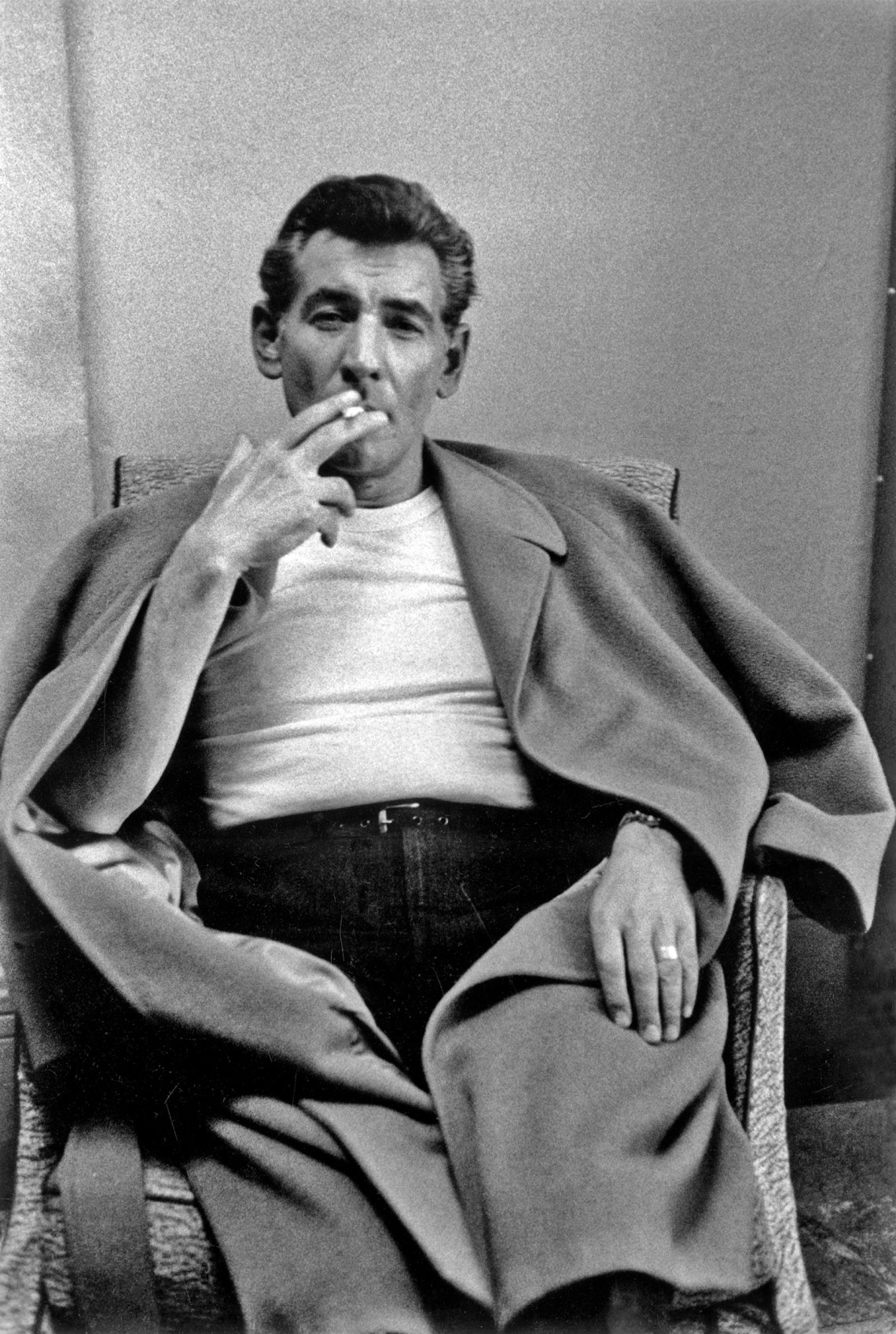

I’ve replayed that encounter, in 1986 at London’s Barbican Centre, in my mind countless times. A BBC documentary filmed two years earlier, shadowing Bernstein as he recorded his musical West Side Story, had rocked my world. I already adored jazz and had immersed myself in modern music of various kinds, and here was a magician with the ability to pour everything I liked—from Igor Stravinsky to Duke Ellington—into the same composition. My time with Bernstein lasted no more than fifteen seconds, but I left that night determined that music would be my life. My older cousin Maria, who accompanied me to the concert, remembers vividly the sheer glamour of the occasion: Bernstein draped in a dressing gown, with a glass of whiskey in one hand and a cigarette holder in the other, surrounded by minders and aides, looking like the embodiment of pure showbiz.

Anybody hoping that Bradley Cooper’s Maestro might provide answers to the central Bernstein enigma—how his populist Broadway instincts fit together with the man who taught generations of Americans about classical music, from Bach to Ives—will likely leave the cinema disappointed. Cooper’s adenoidal delivery of his lines will make you wonder if the maestro suffered a lifelong nasal drip, but he excels at looking like Bernstein, until he attempts to conduct. He has spoken of his film as a love story, and its focus is almost entirely on the complexities of Bernstein’s marriage: the attempts he made to reconcile a sincere devotion to his wife, Felicia Montealegre, and their three children with his attraction to—and brief flirtations and full-on affairs with—men. Carey Mulligan steals the limelight as Felicia.

Netflix was never likely to green-light a film whose hook was the story of Bernstein the musician: Lenny the showman is readily understood; the stylistic labors of a composer caught between tradition and advance are not. Questions about how Bernstein had the chutzpah to imagine one piece I heard at the Barbican, his symphony The Age of Anxiety, in which compositional techniques borrowed from Arnold Schoenberg and Stravinsky smash into big-band exuberance reminiscent of Count Basie, or how he reinvented the fundamentals of American music theater in West Side Story, are therefore never broached.

A few basic facts set Maestro rolling. Bernstein makes his legendary debut with the New York Philharmonic in 1943, filling in for a flu-ridden Bruno Walter, but the particulars that lead him to becoming the orchestra’s music director in 1958 are all but ignored. In a head-scratching scene near the film’s beginning, Lenny discusses his new ballet Fancy Free—written in 1944—with Felicia and concludes that he won’t be taken seriously as a musician because this music “isn’t serious.” Fancy Free might have been rooted in swing-era jazz and early Broadway, but the sheer compositional élan with which he transformed those sources, adopting polytonality and tricks of melodic development from Stravinsky, was deadly serious—as the real Bernstein would no doubt have been the first to remind anyone who asked.

Later, during an eerily precise recreation of a 1955 interview in which Lenny and Felicia in their apartment field questions from Edward R. Murrow in a television studio, the issue emerges of the tension between Bernstein’s existence as a conductor basking in public adoration and the private life of a composer with only pencil, manuscript paper, and piano for company. Cooper’s Bernstein momentarily loses his breezy confidence as he is forced to ponder this inner life lurking behind the public exterior. In the real interview the tension was about music, although we’re under no doubt that the Bernstein of the film is thinking about his personal life.

Maestro’s narrow focus on the personal has the unfortunate, and presumably unintended, effect of skewing the unique breadth of Bernstein’s achievements as a musician. Professionally he worked with Glenn Gould and Maria Callas, John Cage and Louis Armstrong, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Kiri Te Kanawa, Elliott Carter and Stephen Sondheim, Stravinsky and Dmitri Shostakovich, who ought to have been allowed to flood the film with personality and color while posing the essential question: Who else could crash musical boundaries like Bernstein? Aaron Copland (played by Brian Klugman) appears because he was Bernstein’s mentor. David Oppenheim (Matt Bomer), a clarinetist and subsequent executive at Columbia Records, appears because of his romantic entanglement with Bernstein. But the film says nothing about how Copland’s inclination to perch compositions between the “serious” and the “popular” rubbed off on his young charge, while Oppenheim, barely a footnote in the story of American music, seems an oddly inconsequential figure on which to peg so much of the film’s emotional arc, especially given the characters we could, should, be watching interact with Lenny.

Advertisement

Head-spinning cultural overlaps embraced by the real-life Bernstein, which he regarded as essential to the life of a musician, are hardly difficult to find. I’m imagining a dramatic sequence—not in the film—of Bernstein’s attempt, on February 9, 1964, to lead the musicians of the New York Philharmonic through John Cage’s chance operations–based Atlas Eclipticalis, which ended with him quelling a mutiny as the musicians began ridiculing Cage onstage. What human drama! That scene, in my film, would be followed by a jump cut to a year later, to a famous photograph brought to life of Bernstein, fingers jammed firmly in his ears, at a Beatles concert.

Then the camera would pan to a young woman, Ruth Selman, who, in the same year Bernstein had his brush with the Beatles, wrote to him to register her displeasure at the appearance of the twelve-tone composer Anton Webern’s Symphony, op. 21 at a Philharmonic concert, paired with Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. My camera would follow Bernstein’s words as he typed his reply: “It is the duty of any Symphony Orchestra—particularly that of a cultural capital like New York—to keep its audiences abreast of main currents of 20th century music.” And then he pointed out that the Webern symphony, four decades old, was a mere eight minutes long, and there would be big trouble ahead indeed if even this piece—“already a classic”—could not find acceptance on a Philharmonic program.

He might have explained, but didn’t, that Webern’s music was a distillation of Mahler’s expressive and gestural largesse and that his program had been designed to plot a trajectory between Mahler and the emergence of twelve-tone music, spearheaded by Schoenberg, Webern’s teacher. But we see that his attention is instead distracted by a letter in his pile of correspondence from Barbra Streisand, whose latest album, My Name Is Barbra, took its title from a song in Bernstein’s song cycle I Hate Music, and was recorded only a few months before Bernstein began thinking through his program of Webern shaking hands with Mahler.

Another possible sequence: Bernstein leads the premiere of Elliott Carter’s dazzlingly labyrinthine Concerto for Orchestra in February 1970, becomes caught up in a scandal after Felicia hosts a fund-raising party for the Black Panthers at their apartment, then jets off to conduct a performance of Verdi’s Requiem at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, featuring Plácido Domingo. Cage, the Beatles, Webern, Mahler, Streisand, Carter, Domingo, Black Power politics—these are the type of cultural juxtapositions that take you to the essence of Bernstein.

The absence of any reflections in the film on his politics came as a genuine surprise. After having his passport revoked in 1953, Bernstein was stalked by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI for three decades. The Black Panther incident—gleefully satirized in Tom Wolfe’s essay “Radical Chic”—has often been used to batter the Bernsteins, and here was an opportunity to correct the record. (In short, according to the account on the official Bernstein website, the party was organized by Felicia, and Lenny arrived late after finishing a rehearsal of Beethoven’s Fidelio. Black Panther members had been held in jail for nine months without trial. There were widespread concerns at the time over civil liberties.)

But that assumes levels of complexity Maestro proves unwilling to countenance. Motion pictures are no place for musical analysis, but onscreen Lenny is wretchedly one-dimensional: no meaningful connection is made between his tortured personal life and his music-making. He desperately needed to be loved—“I love people” is a mantra repeated throughout the film—but he also craved relevance, which landed him in the middle of an artistic and aesthetic crisis. His reply to Ruth Selman stops me dead in my tracks whenever I come across it. Bernstein might have hankered after adoration but was not beyond telling an audience member to, essentially, suck it up and listen harder.

Advertisement

Opting to couch his rebuttal in terms of performing Webern as a “duty” could be read as implicit agreement that Bernstein, too, would rather have been conducting George Gershwin or Samuel Barber, not this austere, angsty music by a composer—with Nazi sympathies besides—whose work felt so obviously out of step with the pizzazz of 1960s New York. Atlas Eclipticalis blew up in his face because the concept behind Cage’s score required Bernstein’s musicians to learn stretches of fearsomely demanding music that, to their despair, they realized might or might not be heard by the audience, depending on whether individual contact microphones, controlled by chance procedures, were switched on or off. He could have made life easy for himself by programming the accessible new music—by Copland, Virgil Thomson, or Benjamin Britten—with which he had such affinity and which he performed so brilliantly. Or by programming no new music at all. Yet he doggedly went out on a limb, filling his concerts with music by composers considered awkward modernists, such as Edgard Varèse, Pierre Boulez, György Ligeti, Iannis Xenakis, and Morton Feldman.

Bernstein’s teacher, the eminent Russian émigré conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1924 to 1949 and appears only briefly in Maestro, had been an inveterate commissioner of new compositions, from major figures like Stravinsky, Bartók, Hindemith, and Messiaen, and became the model for how to mix and match the old and the new. Old certainties and the speculative new also characterized many of Bernstein’s 1960s programs. Feeling that he understood the instincts of his orchestra intuitively, in 1964 he pursued that speculative new to its logical end point by recording a free improvisation with the New York Philharmonic that appeared on an LP alongside music by Ligeti, Feldman, and the Improvisations for Orchestra and Jazz Soloists by Larry Austin, which pitched take-no-prisoners free jazz improvisers—Don Ellis (trumpet), Barre Phillips (bass), Joe Cocuzzo (drums)—against the orchestra. That same year Bernstein brought free jazz to a Young People’s Concert with Journey into Jazz by Gunther Schuller, a piece he described as a “sort of Peter and the Wolf of jazz,” again involving Ellis and Cocuzzo, and also Eric Dolphy, the visionary alto saxophonist, flutist, and bass clarinetist who was at the time working with John Coltrane and Charles Mingus.

Bernstein’s love of jazz manifested itself most visibly in the recordings he made with some of its brightest stars, including Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, and Dave Brubeck; Billie Holiday recorded his song “Big Stuff.” But his engagement with jazz ran far deeper than is widely appreciated. Proclaiming Ornette Coleman as the future while many jazz critics were still struggling to grasp Coltrane, Bernstein actively sought out the inscrutable pianist and composer Lennie Tristano, visiting his apartment to play piano and have long conversations about music into the night. Bernstein told Tristano’s alto saxophonist of choice, Lee Konitz, that the elegant, snaking melodic lines in “Cool” from West Side Story had been inspired by Konitz’s own improvisational wizardry. Having brought jazz to his Young People’s Concerts, Bernstein also embraced pop, using the latest hit records by the Kinks and the Beatles to demonstrate musical modes and scales.

Simultaneously with all this activity, he carried on with the duties of an orchestral artistic director: illuminating Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms anew, performing Handel’s Messiah at Christmas, continuing his work of proselytizing on behalf of symphonies by Mahler and Carl Nielsen—mainstream figures today, niche concerns in mid-1960s America. But Bernstein’s commitment to modern composition, while never the life mission that it was for his eventual successor at the Philharmonic, Pierre Boulez, was clear. No doubt he disliked some of the new music he conducted, some of it intensely, although any new piece was given the full attention to detail he would lavish on a Mahler symphony. He was also proactive, seeking out scores by the experimental English composer Cornelius Cardew, and he clearly found much to stimulate his ears and intellect in music by Ligeti and other composers he programmed, such as Lukas Foss, Roberto Gerhard, Hans Werner Henze, and Henry Brant. Bernstein realized that his job in New York was, sometimes, to park his own taste and play music that spoke to wider cultural concerns.

Why his engagement with modern composition has been so regularly misunderstood or simply ignored is therefore a fair question, and the first person who must be hauled over the coals for mispresenting Bernstein and modern music is Bernstein himself. In interviews, in his writings, and at considerable length as he delivered the Norton Lectures at Harvard in 1973, he spoke up unambiguously in favor of tonality, the key-based system of organizing composition that had held firm for four hundred years or so, until Wagner, Mahler, Debussy, and Schoenberg tipped it toward fragmentation. The implication hung heavy that being pro-tonal meant you were duty-bound to be against Schoenbergian atonality and everything that had resulted from it. This meant that much of the new music—Carter, Boulez, Ligeti—Bernstein had championed on the podium was by definition suspect. What is less often admitted, however, is that many lesser composers, who were wedded to old-school tonality and couldn’t do anything else, used antipathy toward twelve-tone music as a means of self-justification.

But how Bernstein told it and how he, as a composer, actually dealt with the specter of atonality, when Stravinskyan overhauls of jazz harmony as in Fancy Free were suddenly perceived as old hat, turned out to be two notably different things. Between 1964 and 1965 he took a twelve-month sabbatical from his Philharmonic duties to compose what looked on paper to be a certain success: a musical based on Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth, which reunited him with Betty Comden and Adolph Green, who had written the book and lyrics for On the Town, and Jerome Robbins, who had conceived, directed, and choreographed West Side Story. But Bernstein quickly became stuck and turned his attention instead to a commission from Chichester Cathedral in Sussex, England, for a piece to be performed at its 1965 summer music festival. Looking back in 1977, Bernstein spoke of his Chichester Psalms as “the most accessible, B-flat majorish tonal piece I’ve ever written” and, in confessional mode, added that most of his sabbatical year had been squandered “writing 12-tone music and even more experimental stuff. I was happy that all these new sounds were coming out; but after about six months of work I threw it all away. It just wasn’t my music.”

After he tried denying himself the fulfillment of tonal resolutions, Chichester Psalms became compulsively tonal, an affirmative and optimistic oasis of calm between the two milestone works that surrounded it in his output: Symphony No. 3, Kaddish and Mass, both marinated in turbulence that was spelled out musically as Bernstein apparently baited tonal certainty using atonality and other techniques borrowed from the experimental music he had conducted. The British conductor and composer Oliver Knussen, remembering Bernstein after his death in a BBC documentary, came closer than most to pinpointing how his idea of tonality actually operated: “He was a very experimental figure, not maybe in terms of the notes he wrote down, but in terms of the concepts.”

Kaddish and Mass were surely foremost in Knussen’s mind when he also noted that these conceptual risks were rooted in Bernstein’s “extraordinary performer’s self-confidence”: he knew how to make even the most unlikely concept spring to life onstage. The twelve-tone and experimental ideas with which he had toyed during his sabbatical likely related to a never-completed piano concerto project announced in The New York Times, not the abandoned Skin of Our Teeth, melodic strains of which ended up slotting seamlessly into Chichester Psalms. But Kaddish as a point of departure for further experimental exploration feels perfectly plausible. Mostly finished before the Kennedy assassination in 1963, revised in its aftermath, then dedicated to the memory of JFK, the piece thrashed out a crisis of religious faith, using musical material to model it.

Marin Alsop—one of Bernstein’s best-known former conducting students—told me in an interview shortly after she recorded the piece in 2012:

The journey of this symphony from atonality towards tonality symbolized a huge issue for Bernstein. He endured stinging criticism for writing tonal music, and in this piece atonality represented crisis, an erosion of faith, while tonality symbolized unity and hope.

Felicia was the narrator on the first recording, in 1964, and Bernstein’s text—in which the narrator picks various fights with God—has tended to attract more commentary than the audacious music, none of it favorable. But his lyrical instincts, pockmarked by the ugliness of recent events, carry a narration that was never designed to stand on its own and embodies the idea in Judaism that faith is not a given: one could argue with the Almighty, blaspheme even. There are passages of unbarred material, inside which quasi-Cageian chance procedures shuffle the harmonic pack, as apocalyptic percussion cadenzas plucked directly from Messiaen or Carter keep unraveling the atonal networks Bernstein unleashes. Finally, increasingly insistent tonal patterns take flight, and the piece hurtles toward resolving around pure G major—the struggle to get there refreshing its appearance, a familiar marker arrived at via a previously untraveled route.

Bernstein thought that one had to fight to be a tonal composer in the 1960s and 1970s, and he was determined to lead the charge. Atonality might have come to represent crisis and an erosion of faith, but composers from Monteverdi and Bach onward had always found ways of molding harmony to symbolize crisis, suffering, and pain, and I wonder how many tonality-versus-atonality critiques rest on basic misunderstandings of musical function and, at the most lowly level, of tonality as always happy and beautiful, atonality always ugly and sad. As the final number of his music theater piece Candide, “Make Our Garden Grow,” attests, nobody could write uncomplicated affirmation like Bernstein, but tonality for him could never just be blind affirmation. Composition needed to express doubt and disorientation, too; affirmation sometimes needed to be tested against uncertainty—as Mahler, his greatest hero, had showed.

Even West Side Story, by far the most popular music he wrote, is underpinned by edgy harmonic ambiguity: its opening phrase, played by a decidedly Duke Ellington–like alto saxophone, is pegged around a tritone, the one tonal melodic interval that steps outside simple resolution, signaling that this musical will be exploring conflict and violence. Bernstein continued to press the case for tonality, then went his own way. He never took any interest, at least publicly, in the renewal of tonality by Philip Glass, Steve Reich, or John Adams. His final major orchestral work, the rather shambolic Concerto for Orchestra Jubilee Games, completed in 1989, proved defiantly tonal and experimental, the “games” in its first movement involving free improvisation, slabs of chance in which musicians chose their own pathways through free-hanging melodic threads, and short sequences recorded live that were to be dropped in over later sections of the music, crashing through the real-time performance.

This is where the plotlines in Maestro ought to coincide. Bernstein, plagued with doubt about the direction of music and society and about his sexuality, wrote tonal music but simply could not ignore the lessons of musical modernity; he was always pulled two ways at once. Bernstein, who aimed not just to perform Mahler but to make each symphony come alive onstage, was never happy to put well-used tonal patterns on paper when composing, either. Tonality must live, too. Often he was accused of borrowing remorselessly from Copland, Stravinsky, and Hindemith, from jazz, Latin music, and pop, but he also borrowed from Messiaen, Cage, and Carter. Bernstein’s music was largely about finding a tonality relevant to him and his time, and Maestro defaults too easily to the tortured artist stereotype, without any explanation of what exactly tortured him.

Presumably this is why the first performance of Mass, written for the inauguration of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., in 1971, becomes a mere plot device in the film to tell of Lenny and Felicia’s fragmenting relationship, after he takes up with “Tommy” (in reality, Tom Cothran, his assistant, whose extensive role in his life is soft-pedaled in a way David Oppenheim’s isn’t). This is frustrating because Mass, Bernstein’s great work of summation, is essential to understanding the man and his music. It splutters into existence with webs of prerecorded atonal fragments that boomerang around speakers dotted through the hall, before a brazenly tonal guitar chord initiates a song that sounds like pure Simon and Garfunkel or the Byrds. The piece sets up expectations of abrupt stylistic disconnect, after which all hell keeps breaking loose, as the 4/4 of marching bands and rock songs continues to topple over into the atonal abyss. Approaching the climax, the entire company is invited to improvise over a churning rock riff, then the opening tape music is layered over the top before musicians are encouraged to work “anything from the entire musical literature” into the resulting montage. Like Kaddish, the piece ends in the embrace of a tonal resolution, but only after tonality has been dragged through a discursive and disorientating journey.

Thirty-four years after his death, Bernstein’s name has become shorthand for an obsessive eclecticism, for chiseling away at assumptions about high art and popular culture, and for the unique gift he had for explaining thorny, sometimes esoteric music in simple terms; nobody informed, educated, and entertained like Lenny. Another word never far from any debate about him is “taste.” We’re told that his Mahler was overcooked and self-indulgent (actually it was highly disciplined and focused) and that pieces like Kaddish and Mass ultimately failed because he couldn’t control his outbreaks of questionable taste.

I think we need to look at that argument about Bernstein’s taste from the other direction. New classical music I hear today too often feels risk-averse and suffocated by narrow perceptions of good taste. Unafraid to park his own taste when programming concerts, in his music Bernstein pushed beyond what he already knew tonality could be in search of fresh expressive terrain, challenging his own taste as well as that of others. Tonality mattered too much to him to hear it reduced to generic, good-taste patterns pressing harmonic buttons that would guarantee a particular emotional response.

One former Bernstein pupil, the conductor Neil Thomson, who studied at Tanglewood in 1989 and is now principal conductor and artistic director of the Goiás Philharmonic Orchestra in Brazil, told me recently that while they were working on Brahms’s Fourth Symphony, Bernstein looked up mournfully. “He said, ‘I could die happy if I had written that,’” Thomson remembered. “He looked genuinely sad, and it was a touching moment, as though working on this music revealed insecurities about his own music.” Bernstein, at his best, burst through insecurity to say fresh and startling things—and, returning a compliment once delivered to a nervous schoolboy: Lenny, you always had great taste.

This Issue

February 8, 2024

Who’s Canceling Whom?

Ethical Espionage