Antisemitism has appeared in many times and places—and, as David Anthony shows in his informative, unsettling Sensationalism and the Jew in Antebellum American Literature, in many genres. Anthony has unearthed hostile portraits of Jews in various realms of US culture during the two decades before the Civil War: in pulp fiction, in novels about southern plantation life, in political cartoons, in stage performances, and in literary works like Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun. Anthony demonstrates that the Jew as villain—materialistic, scheming, sometimes sexually aggressive—was a common stereotype in the pre–Civil War era. But he also reveals that many non-Jews expressed ambivalence, depicting Jews as menacing yet enticingly exotic.

Much of Anthony’s focus is on Jewish characters in sensational novels. It has been said that nineteenth-century America was mawkishly sentimental—a culture of pap and prudery against which serious authors like Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, and Walt Whitman rebelled. To some extent this was true, as evidenced by the era’s didactic novels, religious tracts, and codes of proper decorum. It was an age when Evangeline St. Clare, the angelic heroine of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best seller Uncle Tom’s Cabin, inspired millions, and when, in polite circles, undergarments were called “unmentionables,” legs “limbs,” men’s trousers “continuations,” and a trip to the bathroom “visiting Aunt Jones.”1 But there was a lurid underside to antebellum popular culture that bristled with bloodcurdling, yellow-covered pamphlet novels, erotic tableau vivant shows in which naked women posed in scenes like Venus Rising from the Sea or Susanna in the Bath, and penny newspapers full of accounts of homicides, illicit sex, horrible accidents, and the like.

In exploring this seamy side of antebellum America, Anthony follows many critics who have examined nineteenth-century sensational culture over the past several decades. But he is the first to highlight Jewish characters. He discusses, among others, Gabriel Von Gelt, a money-hungry figure in George Lippard’s The Quaker City, the kidnapper and pimp Jew Mike in George Thompson’s Venus in Boston, the corrupt pawnbroker Isaac Jacobs in Emerson Bennett’s The Artist’s Bride, and Jewish women who use sex to lure Gentile men into murder schemes in shocker novels like The Beautiful Jewess, Rachel Mendoza, and The Life, Confession, and Execution of the Jew and Jewess.

In Anthony’s account, these pulp fiction characters are cartoonishly wicked. The Jew appears as a more complex figure in several proslavery plantation novels that he analyzes, including Maria Jane McIntosh’s The Lofty and the Lowly, Harriet Hamline Bigelow’s The Curse Entailed, and Eliza Ann Dupuy’s The Planter’s Daughter. In these works, the Jewish creditor demanding payment represents the intrusive northern capitalist who threatens the southern values of chivalry, honor, and disdain for new money. However, as Anthony points out, the South’s slave system was itself ruthlessly commercial, so that the creditor also embodies the money-centric instincts of southern enslavers: “Like a figure in a recurring dream, the Jew of these novels, so nakedly avaricious, is the projected image of the capitalist greed underwriting slavery itself.”

One of the most revealing figures in Anthony’s book is Rachel Félix, the Jewish tragedienne from France who captivated American audiences while on tour in the 1850s. Dubbed the “Jewish sorceress,” Félix aroused spasms of “enthusiasm…fevers and nervous flustrations” in audiences. Along with her thrilling stage presence went gossip about her scandalous behavior; she had many famous lovers and two illegitimate sons. Constantly pressuring her managers to maximize profits, she drew comments like this from reviewers: “The veriest Shylock of her race is not more keenly alive to the value of money than is Rachel. ‘She is not a Jewess—she’s a perfect Jew,’ said some one [sic] who wished to give epigrammatic intensity to the expression of the general sentiment.” A dark-haired, luminous beauty, she was mesmerizing and, to some, threatening. One theatergoer reported, “The mere glance of her eye had a fiendish fascination—it made me shiver from head to foot.”

Similarly mixed feelings characterized Hawthorne’s response to Emma Abigail Salomons, a young Jewish woman he met at a function during his time as an American diplomat in London. The sister-in-law of David Salomons, London’s first Jewish lord mayor, Emma provoked an ambiguous entry in Hawthorne’s English Notebooks: “She was, I suppose, dark, and yet not dark, but rather seemed to be of pure white marble, yet not white; but the purest and finest complexion…that I ever beheld.” Her hair was “black as night, black as death”—not glossy like a raven’s wings but deep, “wonderful hair, Jewish hair.” Her nose, which was “Jewish too,” had a “beautiful outline”: so lovely that it would make any attempt to capture it in language or sculpture “despicable.” And yet, Hawthorne says, “I never should have thought of touching her, nor desired to touch her,” because

Advertisement

whether owing to distinctness of race, my sense that she was a Jewess, or whatever else, I felt a sort of repugnance, simultaneously with my perception that she was an admirable creature.

As Anthony shows, Hawthorne’s response to Salomons seems to have influenced his description of Miriam Schaefer, one of the main characters in his last major novel, The Marble Faun. Hawthorne tells us that Miriam “had what was usually thought to be a Jewish aspect,” with a complexion that was fair but not pallid and “black, abundant hair…. If she were really of Jewish blood, then this was Jewish hair.” She is rumored to be the daughter of “a great Jewish banker.” An artist, she is obsessed with painting violent Jewish women: Salome with the head of John the Baptist, Judith with the head of Holofernes, Jael driving a nail into the head of Sisera. Beautiful and magnetic, Miriam also has criminal tendencies. She exults in a murder committed by a suitor. In contrast to her friend Hilda, an optimistic Protestant, Miriam is given to brooding and self-doubt. Anthony notes that “Miriam, like Salomons, is the very embodiment of ambivalence for Hawthorne.”

A deft close reader, Anthony devotes a section of his book to Cecil Dreeme by Theodore Winthrop, a lawyer and writer who served in the Union Army and was killed early in the war. Published posthumously, Cecil Dreeme was his most important novel and has recently attracted new attention. Anthony joins other critics in probing the queer relationship between the narrator, Robert Byng, and Cecil Dreeme, a man who in the end turns out to be Clara Denman, a woman disguised to hide from an arranged marriage with Densdeth, the novel’s Jewish villain. Byng confesses to having a love “passing the love of women” for the apparently male Dreeme while also feeling pulled toward Densdeth. A well-traveled, cosmopolitan figure who is compared to the legendary Wandering Jew, Densdeth is charming but manipulative. Byng wonders “why [Densdeth] captivated me,—why he sometimes terrified me,—why I had a hateful love for his society.” Elsewhere Byng says of him, “Name and man are repulsive; but attractive also. Attractive by repulsion.” Anthony plausibly argues that Byng is projecting uncertainty about his own sexual identity onto the Jew. Densdeth finally reveals his underlying criminality when he kidnaps and holds prisoner Dreeme/Denman.

Anthony also calls attention to two Jewish characters in Walt Whitman’s recently discovered serial novel Life and Adventures of Jack Engle: An Auto-Biography. Published in the New York Sunday Dispatch in 1852, three years before the appearance of his magnificent poetry volume Leaves of Grass, Jack Engle attests to the fact that many of America’s greatest writers occasionally dabbled in popular genres, in this case the sensational urban novel. A subplot of Whitman’s novel involves Engle’s meeting a Jewish woman, Madame Seligny, who runs a “fashionable gambling house” with her daughter. An obese, bejeweled woman with “a hooked nose, and keen black eyes,” Madame Seligny pretends to be an aristocrat but may be, Whitman writes, “an old Jewish tradeswoman” who exudes sordidness. Her tall, slender daughter, Rebecca, is described as “a pretty good specimen of Israelitish beauty” who “dressed with some taste, although richly, and with a little of her national fondness for jewelry.” This “pretty Jewess” has a relationship with Engle’s friend Tom Peterson. But Peterson says that despite his strong attraction to Rebecca, he does not love her, because “the woman I love must be—; but never mind what.” Anthony suggests that Peterson could only think of loving a Christian. Whitman resolves the situation by having the young woman and her mother move abroad at the end of the novel.

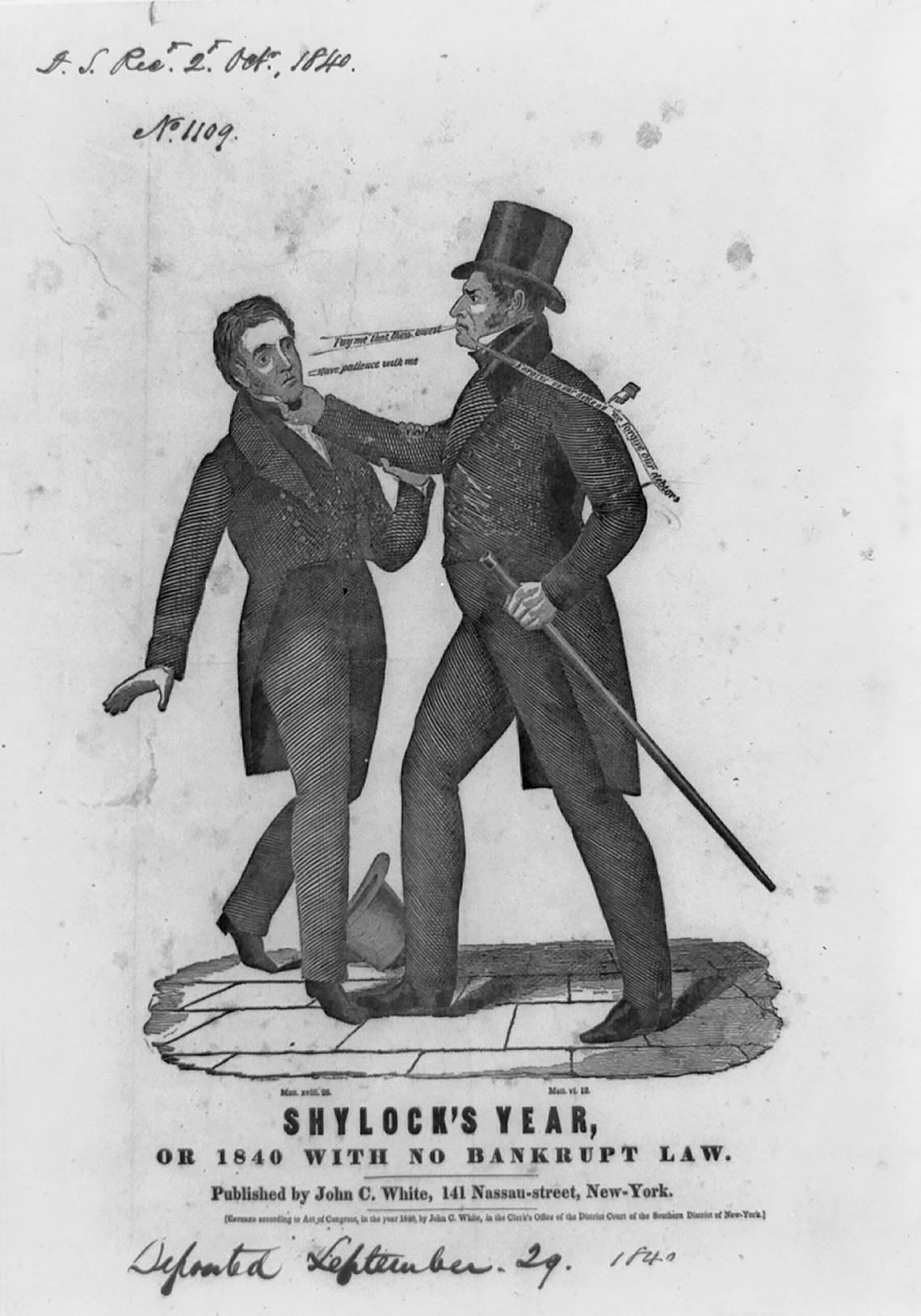

Anthony’s book also contains political cartoons that vivify the era’s antisemitic stereotypes. In an 1834 lithograph, a greedy Jewish stockbroker is undermining the nation’s economy by hoarding gold bullion that he uses to buy up Andrew Jackson’s “pet banks” at cheap prices. Shylock’s Year, or 1840 with No Bankrupt Law depicts an angry Jewish moneylender choking a Gentile man who cannot repay a debt because of Congress’s failure to act on bankruptcy protection. The Height of Madness, a cartoon of 1864, shows a Jewish Mr. Shoddy in the act of stabbing the American eagle with a sword labeled “Bogus Speculation”—a reference to rapacious businesspeople who produced shoddy, a flimsy cloth made of glued rags that quickly tore apart when used for Union military blankets, uniforms, and tents.

In his discussions of such visual images, Anthony opens up his perspective to politics and society. The literary analyses that dominate the main sections of his book, while perceptive, sometimes make us feel trapped in a critical hothouse. The book gains substance when it turns to actual people and events. Anthony highlights the experiences of several prominent Jews, such as the newspaper editor Mordecai Noah, who was accused by a Gentile rival of leading a Jewish conspiracy against Christians, and Judah Benjamin, the Confederate cabinet officer who was frequently charged with sapping the South’s economy by condoning, in the words of one politician, “foreign Jews…scattered all over the country, under official protection [from Benjamin], engaged in trade to the exclusion of our own citizens, undermining our currency.” Anthony also makes note of notorious antisemitic actions, such as General Ulysses S. Grant’s 1862 expulsion of Jews from his military district.

Advertisement

Grant’s expulsion order (revoked at President Lincoln’s command) occurred amid a surge in antisemitism on both sides during the Civil War. This leads us to reconsider Anthony’s discussion of antisemitic stereotypes in the years before the Civil War, his main area of concentration. There can be no doubt that such stereotypes were widespread, but what was the reality of life for Jews in that period? Actually, America wasn’t as hostile as the stereotypes might suggest. Before the war, the US had been a welcoming place for many Jews arriving from Europe, with its long, awful history of pogroms and disenfranchisement. The historian John Higham writes:

Throughout the antebellum period, Jews continued to enjoy almost complete social acceptance and freedom. There was no pattern of discrimination in the sense of exclusion from social and economic opportunities which qualified Jews sought…although American conceptions of Jews in the abstract at no time lacked the unfavorable elements embedded in European tradition.

Higham adds that the Civil War, with its hysteria over race and politics, brought a flurry of ideological antisemitism.2

On his subject of the Jew in sensational literature Anthony occasionally comes up short. One of the first novels he discusses is George Lippard’s The Quaker City, which he suggests is typical, as when he introduces “antebellum sensationalism—the schlocky, lowbrow genre made up of dime novels like The Quaker City, penny newspapers, lithographs, and other cheap published ephemera.”

I’ve explored such material for years and can attest that there are wide variations in it.3 The penny papers tended to be baldly sensational, following the editor James Gordon Bennett’s principle that American readers

were more ready to seek six columns of the details of a brutal murder, or the testimony of a divorce case, or the trial of a divine for improprieties of conduct, than the same amount of words poured forth by the genius of the noblest author of the times.

Satirical lithographs delivered pungent social messages, as Anthony says, though they caricatured not only Jews but other groups as well, including African Americans, feminists, and politicians of all stripes, from Lincoln to his archrival Stephen A. Douglas.

As for authors of sensational fiction, there were some, like the prolific Ned Buntline, who churned out adventure novels with thrill-seekers in mind, showing little care for teaching political lessons (though the rabidly nativist Buntline took shots at Catholics and Jews). Others, like George Thompson, combined formulaic sensationalism with crude efforts at social commentary. For example, Jew Mike, the figure in Thompson’s Venus in Boston whom Anthony includes among his stereotyped Jews, is both villainous and reformist. An admitted criminal, he is also a vehicle for exposing what Thompson sees as the rampant hypocrisy of America’s social elite. A high-toned housewife who murders to cover up a love affair, a respected newspaper editor who publishes false stories to attract readers, an eminent clergyman who visits houses of prostitution to satisfy his uncontrollable lust—these are just a few of the ruling-class types encountered by Jew Mike, who declares, “As great a villain as I am, I am no hypocrite, and was never accused of being one. And yet hypocrisy prevails in every department of life.”

This theme of universal hypocrisy is handled with greater subtlety in The Quaker City. Anthony, to support his argument that Lippard’s best seller typifies “schlocky” sensationalism, cites the critic Peter Brooks, who associates “the melodramatic imagination” with

the indulgence of strong emotionalism; moral polarization and schematization;…overt villainy, persecution of the good, and final reward of virtue;…dark plottings, suspense, breathtaking peripety.

Anthony writes, “Brooks could well be describing The Quaker City.” It is true that this potpourri of strung-together Poe-like mysteries is full of strong emotions and dark plots. But it jettisons moral polarization. Virtue and vice are situational. In one scene a character can seem worthy and in the next prove to be villainous or deluded. The novel has no moral center. Several ostensibly virtuous characters meet bad ends, while several wicked ones succeed. Anthony includes the rapacious Gabriel Von Gelt among his stereotyped Jews without mentioning that almost everyone in this crowded novel, not just Von Gelt, is grasping and materialistic. Lippard, who was so devoted to social reform that in 1849 he founded the Brotherhood of the Union, an early nationwide labor organization, had deep working-class sympathies that led him to view ruling-class Americans as corrupt and exploitative.4

If The Quaker City was more complicated than Anthony lets on, so was the world of Civil War–era Jews. Take the relationship between Jews and slavery. Some slaveholders, as Anthony contends, saw Jews as mirrors of their own capitalist instincts. Others, however, saw in Judaism a powerful validation of slavery, because Old Testament patriarchs had also held people in bondage. George Fitzhugh, the South’s most outspoken defender of slavery, proclaimed his “unfeigned admiration and approval” for ancient Jews, among whom “the relation of master and slave was truly affectionate, protective and patriarchal,” establishing hierarchical customs that were “practiced by the Jews to this day.” Jews themselves were split over slavery: Orthodox Jews tended to support the institution because of its biblical roots, whereas Reform Jews generally opposed it on moral grounds. There were also predictable attitudinal differences between southern and northern Jews. This divided opinion translated into contending loyalties during the Civil War: around three thousand Jews fought for the Confederacy, seven thousand for the Union.

Although he doesn’t discuss these aspects of the Civil War, Anthony makes an interesting turn to later historical events. He leaps over 150 years—a period when the millions of Jewish immigrants arriving in America provoked a far-spreading conspiracy theory about international Jewry’s alleged scheme to take over the world—to reach our own times. He remarks on the persistence of antisemitism, as seen in the “Happy Merchant” meme of alt-right websites and in the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, where marchers chanted, “Jews will not replace us!” Versions of the old damaging stereotypes, therefore, have not only survived but have intensified, even after the unspeakable horror of the Holocaust. Since Charlottesville we’ve witnessed the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre, the mainstreaming of QAnon (whose core belief about a vast liberal pedophile ring controlling the US government and Hollywood is laced with antisemitism), and the likes of Georgia congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, who on Facebook once blamed California’s forest fires on laser beams fired from space by profit-seeking Jews. More recently the Israel–Hamas war has provoked a resurgence of antisemitism.

In the pre–Civil War period David Anthony describes antisemitic cultural stereotypes balanced by an overall tolerance of Jews in public life. Appallingly, far more toxic antisemitic notions shape the political opinions of many Americans today.

-

1

See R.W. Holder, How Not to Say What You Mean: A Dictionary of Euphemisms (Oxford University Press, 2007). ↩

-

2

John Higham, “Social Discrimination Against Jews in America, 1830–1930,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, Vol. 47, No. 1 (September 1957), p. 3. Anthony’s topic is Judaism, but of course other groups (Blacks, Natives, Catholics) suffered in the era, and in popular literature some, notably Catholics, were arguably treated worse than Jews. Catholics, whose numbers rose from around 660,000 in 1840 to 3.4 million in 1860, seemed more of a threat to native-born Americans than did Jews, whose population rose from 15,000 to 150,000–200,000 in the same period. ↩

-

3

See especially my Beneath the American Renaissance: The Subversive Imagination in the Age of Emerson and Melville (Knopf, 1988). ↩

-

4

See Mark A. Lause, A Secret Society History of the Civil War (University of Illinois Press, 2011), chap. 1; David S. Reynolds, George Lippard (G.K. Hall, 1982), chap. 1; and George Lippard, Prophet of Protest: Writings of an American Radical, 1822–1854, edited by David S. Reynolds (Peter Lang, 1986), chap. 3. ↩