In 1978, at the age of seventy, Barbara Comyns jotted down a new idea for a novel:

I’ve an idea for a book—“Waiting.” Elderly people retiring to a new little house on a garden estate waiting to die but things keep happening. They feel even more intensely than when they were young. Some good things happen, some exciting and some almost horrifying.

A year later she sent the manuscript, which sounds a bit like Beckett’s Endgame, to her agent. Publishers said they liked it, but no one took it on; they didn’t think it would sell. Comyns protested: “There may be a revival of interest in my books in the not so distant future. Remember Barbara Pym!” And she was right. By the 1980s she was one of Virago’s celebrated writers (she died in 1992), after the new feminist press discovered and reissued her gothic-tinged novel The Vet’s Daughter (1959).

Other reprints and previously unpublished novels of hers appeared to acclaim in that decade without quite pushing Comyns into the canon of twentieth-century British literature. (The attention also failed to help Waiting, which never did get published.) Now, more than three decades after Comyns’s death and following fresh revivals of her books in the twenty-first century, the British scholar Avril Horner has written a biography. As an indication of how obscure even basic facts about Comyns’s life have become, the capsule biography on almost all the recent reissues puts her birthdate at 1909 rather than 1907. (She kept it a secret all her life.)

Despite these upwellings of popularity over the years, the sui generis quality of her writing makes it seem liable to slide again into oblivion, requiring yet another rediscovery. But this is one of the pleasures of reading Comyns, the feeling that you’re unearthing something akin to outsider art. Although it’s not outsider art—she didn’t have much formal education, but she was well read and even wrote a book about Leigh Hunt (now lost) that Graham Greene tried to get published—her work has a disorienting vitality to it, as if it gave birth to itself without bothering to look around for parents.

Starting at the age of forty, Comyns published eleven short novels. Only five of them are strongly autobiographical, but she leaned on aspects of her life in all her work. The best known are Our Spoons Came from Woolworths (1950), about a young mother and aspiring sculptor trying to survive poverty in 1930s London; Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead (1954), about a Warwickshire village during the outbreak of a mysterious plague in 1911; The Vet’s Daughter, about a teenager with a villainous father in Edwardian London who under extreme stress becomes able to levitate; and The Juniper Tree (1985), a Grimm-infused tale of a single mother with a biracial daughter who accidentally (in her telling) kills her spoiled, rich stepson.

The novels that don’t get talked about are equally worth reading, particularly Mr. Fox, written in the 1940s and published in 1987, about a single mother getting by with her racketeering boyfriend in London during World War II, and The House of Dolls, written in the 1960s and published in 1989, a tale of middle-aged women supporting themselves as prostitutes in a London boardinghouse. A reader might prefer one book to another, but their power is cumulative: the more you read of her, the more idiosyncratic her body of work seems in its blend of dailyness, unreality, menace, and humor. It is unsurprising to learn, in Horner’s illuminating biography, that Comyns felt an affinity with the paintings of the self-taught Henri Rousseau.

Comyns has a pictorial eye, and though she wrote stories from a young age, she originally thought of herself as a sculptor and painter. The consciousness and sensibility of her characters come to us through the way they observe things like furniture, clothes, rooms, food, faces, and views, rather than through authorial musing or intricate psychological self-analysis. The intensification of reality that one feels in her books—“realness almost exaggerated,” as she once described her approach in an interview—derives from the solidity of her conversational voice and the objects it describes, which at any moment could slip into the surreal.

In the opening sentence of Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, “The ducks swam through the drawing-room windows,” a freedom they’re able to enjoy because the river has flooded and overrun the house, making the grounds a topsy-turvy mix of the dreadful (drowned hens, dead peacocks, a bloated cat) and the enchanted:

They sailed out again to explore the wonderful new world that had come in the night. Old Ives stood on the verandah steps beating his red bucket with a stick while he called to them, but today they ignored him and floated away white and shining towards the tennis court.

Later, things dry up, but the saturation of reality doesn’t: “Through the stained-glass window she saw her son all crimson following a yellow baker’s wife. Then they changed color and both became green and disappeared from sight”—a quick dip into Fauvism. Depending on the context, or who is looking, the shimmer of unreality will either deepen the horror of a scene or act as a comforting release from it.

Advertisement

For Comyns, realism and surrealism are not mutually exclusive: the supernatural is just another aspect of the natural, while the commonplace always transmits an extrasensory, distorting strangeness. At a midpoint on this continuum, Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead depicts the goings-on of the widower Ebin Willoweed, his three children, his mother, their two servants, and their gardener in a riverside house in Warwickshire during a time of extraordinary disaster—first flood, then plague. Nothing unreal happens—unless you count the chickens that drown themselves after becoming “depressed and hungry”—but everything feels freakish and macabre. After the flood recedes, random villagers go mad and kill themselves. No one knows the cause, but everyone is afraid of catching the possibly viral illness. Once ergot poisoning from contaminated rye bread is identified as the source, people blame the “hideous” baker’s assistant, Old Toby, who was already an outcast because of his scarred face, and mob rule prevails.

Although Comyns generally favors first-person narration, using it in eight of her eleven books, here she adopts an omniscient eye along with her usual loosely plotted structure. Ebin, a “slothful,” self-absorbed man who bullies his children and is in turn bullied by his shouting, partially deaf mother, has lost his job as a gossip columnist after causing a libel suit against his paper. When the mysterious plague hits he discovers that he can peddle lurid articles about it, which he hopes will enable him to stop depending on his mother. His daughter, Emma, in her late teens, looks out for her younger brother, Dennis, and her half-sister, Hattie. The maids, Norah and Eunice, endure mistreatment and have love affairs, while Grandmother Willoweed spars with Old Ives the gardener, the only person she seems to grudgingly respect. The concerns here are familiar for Comyns: the daily struggle to survive; cruelty directed at the innocent; the uneven distribution of suffering; and the relief of unexpected beauty or benevolence.

Though the plot isn’t autobiographical, Comyns drew on her past for the tone of the household and the setting. She grew up as Barbara Bayley in Warwickshire, in a manor bordering the River Avon, a few miles from Stratford. The fourth of six children, five of whom were girls, she spent much of her time running wild outside with her siblings. The pastoral title of her near-memoir, Sisters by a River (1947), would seem to cast an idyllic glow over her childhood, but the blissful moments—rowing on the river, when “I felt I wanted to cry with so much happiness”—mingle with domestic horror, a shadow that haunts many of her books. Her father, Albert Bayley, made his wealth by patenting a new brewing process, but debts piled up, and he became prone to binge-drinking and violent rages.

Comyns, sometimes the target of his beatings, later characterized him as an “impatient, violent man, alternatively spoiling and frightening us.” During one rage, he tried to push his mother-in-law out of her bedroom window. (Her hips saved her.) He also abused his wife. Almost twenty years younger than her husband, Margaret Bayley gave birth to six children by the age of twenty-nine and had emotionally retreated from them long before she went completely deaf, likely from a pregnancy-related complication. When her children spoke to her in sign language she would turn away, saying, “I won’t look at your hands. I hate you all.” In Comyns’s recollection, she “lived the life of an invalid…lying in a shaded hammock on one of the lawns, reading and eating cherries.”

It fell to Granny, Margaret’s mother, to attend to the children and keep them alive. Only two knew how to swim, and Comyns later expressed surprise that none of them had drowned as children. (It is perhaps of these near escapes that she’s thinking when she has Caroline’s little girl in Mr. Fox find “a battered rag doll with seaweed in her hair” and name her “Found Drowned.”) Granny was a superstitious playmate—thrilling and scaring the children with stories of ghosts and spirits, in whose reality Barbara firmly believed until the end of her life—but she was also “formidable,” tormenting the maids and imposing her whims on everyone.

Terrible caregivers feature in almost every Comyns novel. They even crop up in her analogies: in The Skin Chairs (1962), some pet mice are described as “keeping close to the skirting board most of the time. There used to be a girl in our village who was continually beaten by her parents and I remembered she used to walk like that, close against the walls.” But her narrators are always loving to their own children, if they have them. (Comyns was close to her son and daughter all her life; her son, Julian Pemberton, from whom Horner has gleaned much information, became a scene painter and props artist in London and helped design the storm trooper helmets for Star Wars.)

Advertisement

In keeping with the general neglect, the Bayley girls were left to tumble up when it came to education. Although her brother was sent to boarding school from a young age, as a teenager Barbara spent only one year at school. At home the sisters ran through a series of unqualified governesses who could not maintain discipline (Barbara knocked one of them down the stairs for trying to punish her), and nothing was learned. Her spelling forever remained erratic, something a publisher of her early vignettes suggested they not correct, thinking that the occasional error (“Granny used to interfeer a lot”) suited the syntactical unruliness of her prose and the feral scenes it described—of, say, children riding rabbits until they were “squashed.” In subsequent books, her syntax calmed down and her spelling was standardized, which made her style seem only more distinctively her own.

That wild but exact style is always instantly recognizable, a mix of looseness and compression. She will, in the voice of a first-person narrator, casually repeat herself, or use slang like “rather waddy” (small-minded), or hear “lovely little noises,” or call the light “lovely” or a flying bomb “beastly” or a fox a “lovely little thing”—but she always blends this colloquial dash with precise observation: Caroline in Mr. Fox vomits while hungover because she remembers how “at one time in Norway they used to eat bears’ paws for breakfast.” The freedom of her style extends to the unpredictable way she bestows attention, as when she introduces a “broken-down” man who speaks to the narrator about his wife in the opening paragraph of The Vet’s Daughter, then abandons him—he was only a random stranger, it turns out. It’s a gaze that feels lifelike and personal in its arbitrariness.

The familiarity of her tone makes it easy to forget the imaginative distance that went into creating a character. Critics of Our Spoons Came from Woolworths tended to conflate its naive young narrator with the forty-two-year-old author. “Like her heroine, Miss Comyns does not appear to have quite grown up yet,” wrote a reviewer in The Times Literary Supplement. But a more perceptive writer in the Chicago Tribune noted that “its style and the story it tells are strangely reminiscent of Moll Flanders”—which was, Horner has discovered, Comyns’s favorite book.

This feels like a revelatory detail: Comyns’s focus, like Defoe’s, is on the everyday hustle of survival. Both favor swift, episodic narratives. Household economy is always a concern. Defoe’s speakers—particularly Moll Flanders and the courtesan Roxana—beguile us with a chatty yet compact eloquence that Comyns has updated and salted to her own taste. Here is charismatic Moll Flanders talking about the man who first seduced her:

From this time my Head run upon strange Things, and I may truly say, I was not myself; to have such a Gentleman talk to me of being in Love with me, and of my being such a charming Creature, as he told me I was, these were things I knew not how to bear; my vanity was elevated to the last Degree.

And here is Sophia Fairclough in Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, describing the older artist she falls for:

When I talked he listened most intently to every word I said, as if it was very precious. This had never happened to me before, and gave me great confidence in myself, but now I know from experience a lot of men listen like that, and it doesn’t mean a thing; they are most likely thinking up a new way of getting out of paying their income-tax.

Although Defoe’s narrators are much shrewder than Comyns’s, hers know how to subtly, even manipulatively, gain our trust with a display of naiveté and frankness. A friend of Comyns likened her to “one of those wide-eyed wiry little sea-daisies, sort of innocent and fragile and yet tough,” a resilience she lent to her narrators.

At twenty-one, four years after Comyns’s father died and following a miserable stint working in a kennel in Amsterdam, she moved to London, using the £200 she’d inherited to attend the Heatherley School of Fine Art. She dropped out a year later because she could no longer afford the tuition. Although she found a job drawing, typing, and writing copy at an advertising agency, it did not pay well, and she went hungry much of the time, a period she later fictionalized in A Touch of Mistletoe (1967). Feeling disadvantaged by her lack of education, Comyns haunted free galleries and public libraries,

and read until I was almost drunk on books; but my own writing suffered and became imitative and self-conscious. In the end, with great strength of mind, I destroyed all the stories and half-written novels I’d written over the years when I left my dank bed-sitting room to get married.

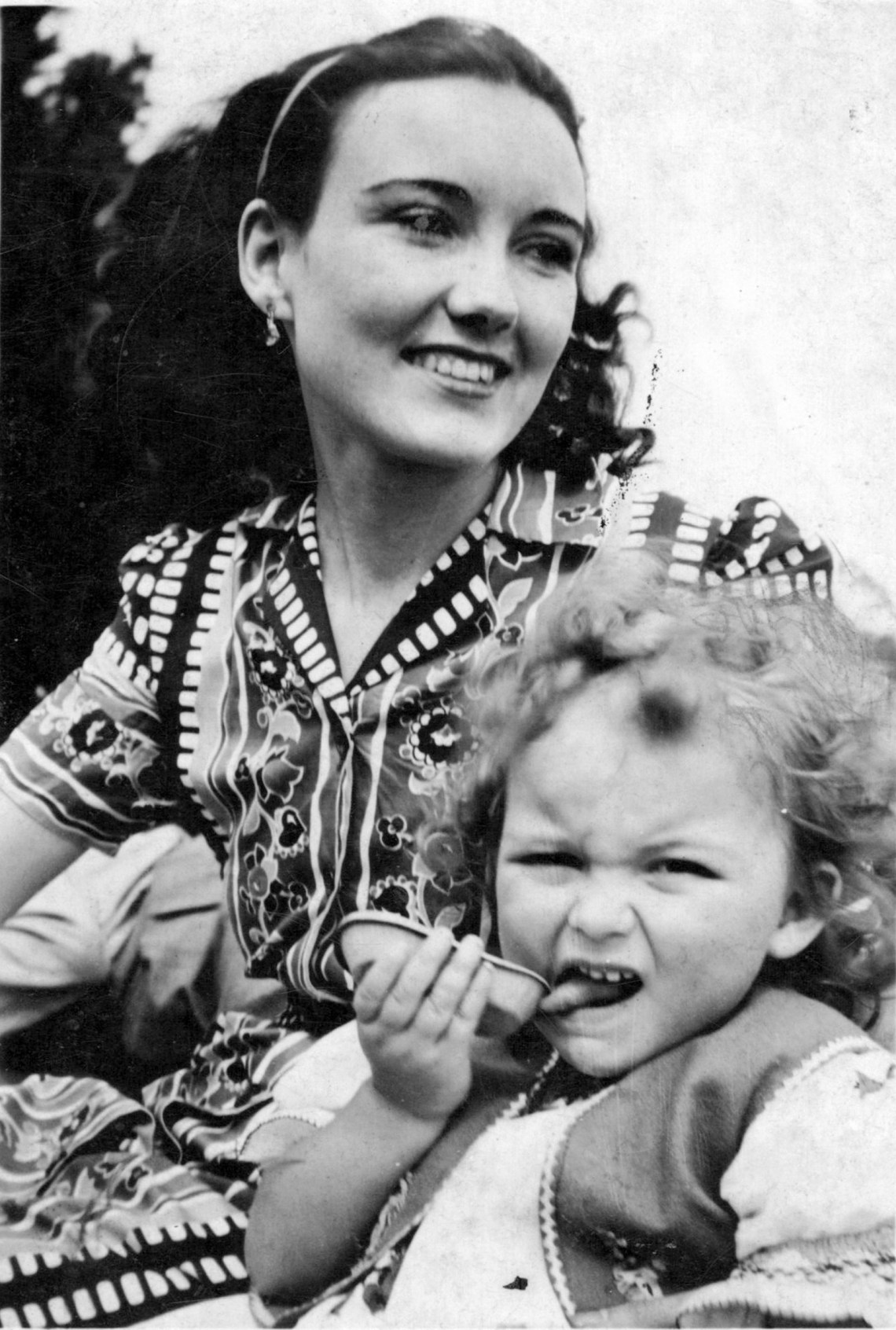

The man she married, at twenty-three, was John Pemberton, a twenty-one-year-old art student whose family in Stratford was acquainted with hers and whom she’d known slightly as a child. She and her sisters used to call him “Little Johnny Head-in-the-Air,” after the character in Struwwelpeter who falls into a river and almost drowns because he can’t stop dreamily staring at the sky. It was a prophetic nickname for a husband who turned out to be insistent on making a living only by selling his paintings. They didn’t often sell, and Barbara, abandoning her own artistic aspirations, was forced into the role of sole breadwinner. That became harder when, in 1932, she gave birth to their son, a miserable experience that she recounts in Our Spoons Came from Woolworths. After the novel was reissued in the 1980s, she was astonished that no reviewer “mentioned how awful it was having a baby” if you were poor in the years before the National Health Service was established. Her treatment at the hospital was appalling, and the fees were cripplingly expensive.

John was no help with the baby, which he didn’t want, and a few weeks after giving birth Barbara went back to supporting all three of them as an artist’s model, taking the baby along with her to sittings. This was the hardest period in her life, which she subsequently referred to as “the poverty.” Their marriage became strained: John began sleeping with others, while Barbara fell in love with John’s dapper and sophisticated uncle, Rupert Lee, a visual artist who was twenty years her senior and the president of the London Group, a major exhibiting society. Through him, Barbara and John met well-known artists, scored passes to art previews (including the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition, which captivated her), and exhibited a couple of their own artworks.

When Barbara got pregnant again, in 1935, she was certain it was Rupert’s, though it’s hard to credit her certainty given her Bloomsbury-like entanglements. Rupert “made love to me in the afternoons, while John had me at night,” she confided in a letter to another one of Rupert’s lovers, Diana Brinton. Barbara wanted to live with Rupert and raise their child together (he was separated from his wife, who refused to divorce him), but it was wealthy, worldly-wise Diana, secretary of the London Group and a decade older than Barbara, who eventually became Rupert’s lifelong companion. Over time Barbara became close friends with her—“You are the only woman outside my family I’m not shy of,” she told her—and despite their initial rivalry, Diana provided her with much material support, paying for her expenses when she gave birth to her second child, a daughter named Caroline, and giving her a weekly allowance. (Neither father offered much child support.) Before everything got sorted out, however, there was much emotional turmoil, including a suicide attempt by Barbara. John’s father threatened to have her declared insane so that they could take away her son (though John himself had no interest in raising him).

“In the back of my mind I was always sure that wonderful things were waiting for me, but I’d got to get through a lot of horrors first,” says Caroline in Mr. Fox, a novel that draws on the next stage of Comyns’s life, with a charming and volatile criminal named Arthur Price, who’d been her landlord and who generally got along well with her children. She joined him in his various money-making schemes and proved a sharp entrepreneur herself, buying and selling used luxury cars, managing a greasy spoon café, redecorating flats, setting herself up as a landlady, and restoring and selling antiques. They moved to Hayes in Middlesex before the Blitz, but life was difficult there because they no longer had Arthur’s racketeering money. His occasional violent outbursts also made her uneasy, especially after he struck four-year-old Caroline, whose clumping feet had woken him up.

Though she did not break up with Price, she gained some independence by moving to Hertfordshire for a couple of years and working as a cook and housekeeper in two successive houses. To entertain her children, she wrote the vignettes eventually gathered in Sisters by a River, several of which sympathetically focus on the family’s maids. (The gulf between the haves and the have-nots is always at play in Comyns’s novels. Sometimes this aligns with familiar class divisions—Alice Rowlands in The Vet’s Daughter sounds like a “little Cockney” to the “lordly” boy she likes—and other times, as in Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, it aligns with Comyns’s own experience as an impoverished woman who grew up uneducated in the upper middle class.) Back in London with Arthur for the second half of the war, she helped him resell grand pianos that weren’t exactly as advertised and bred poodles to supply a late wartime demand for pets.

Although she drew her subject for Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead from newspaper reports of ergot poisoning in France, the novel also seems marked by the collective trauma of World War II. (Perhaps Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year—a fictionalized eyewitness account of the bubonic plague that devastated London in 1665–1666—was another, more oblique, influence.) She was in London in 1944, when Germany was raining missiles on the city in retaliation for D-Day. A street adjoining hers was bombed while she was in her back garden, and she was thrown into the air with the chickens. Her recounting of this near-death experience was, according to Richard Comyns Carr, her second husband, “one of the funniest first-hand narrations I have heard for a long time.”

Richard, whom she met through Diana and Rupert, was the opposite of roguish Arthur, being an upper-class Oxford graduate with a Classics degree and literary aspirations, and he encouraged her writing. Although an austere and reserved man—Barbara first characterized him to her daughter as “Mr. Grey”—he wrote passionate love letters, and his politics were surprisingly radical for an outwardly conservative gentleman: he subscribed to an anarchist magazine and sympathized with socialists. He was drawn to similar contradictions in Barbara, whom he found a startling freethinker despite her delicate, almost Victorian politeness.

By the time Richard married Barbara in 1945, he was working in counterespionage for MI6, in a subsection headed by the infamous double agent Kim Philby. (One of his colleagues and friends in the department was Graham Greene, who soon became a champion and editor of Barbara’s early work.) They were close friends with Philby, who resigned in 1951 after two agents he’d recruited as spies for the Soviets defected; Richard himself came under suspicion and was transferred to a less sensitive department, and eventually fired in 1955. From then on he was under surveillance. The couple was trailed even after they moved to Ibiza to save money.

Barbara always dismissed the idea that Richard was a Russian informant, saying he’d been tarred by association. Horner floats the possibility that he was a double agent, since he was seriously suspected, but he may have gone back to working for MI6 as an undercover agent after the couple moved from Ibiza to Barcelona, where he found work as a journalist. Barbara wrote to her son that “people from the Foreign Office often came to see him,” and whenever her children visited they witnessed Richard “in deep conversation with well-dressed men in dark bars” and were told not to approach.

Although she was never again as poor as in the days of “the poverty,” Comyns became anxious about money when they moved back to England in their late sixties, following eighteen years in Spain and a disastrous experiment living as informal caretakers of Diana Brinton’s estate in Cádiz. Ten years earlier Comyns had written The House of Dolls, a sharp-eyed comedy about the struggles and humiliations of aging women with thin incomes. In an ironic twist on the upstairs–downstairs divide, the middle-class women living upstairs have slid into prostitution and pretend to one another that they grew up in aristocratic splendor, while the person occupying the former servants’ kitchen is the owner of the house and its landlady, whose daughter attends a posh school. As always, Comyns writes about people living on the edge of collapse alongside those who are not, and although she paints these petty, selfish fifty- and sixty-year-old women as grotesques (one has false eyelashes that look like “dehydrated moths”), she also makes them poignant in their precarity, vanity, and diminishing options, and in their efforts to live with flair despite just scraping by.

The novel ends the way many of her novels do, with a sudden windfall that transforms the have-not into a modest have. These precipitous happy endings can feel unreal, even if such things did often happen to Comyns: “The money came just when things were at their gloomiest. I have often noticed that when one is in despair over something and thinks it will never end, it always does, often quite suddenly,” she writes in Out of the Red, Into the Blue, a novel (she called it “three-quarters true”) about her time in Ibiza. But the more she uses serendipity as a governing structure, the more it inadvertently functions as sociopolitical criticism: What kind of society lets a lucky break be the only possible way out of wretchedness?

For Comyns herself, the ending was serendipitous. Money and accolades poured in after her literary revival in the 1980s, when she was in her seventies, though she continued to worry that everything would vanish. As Caroline puts it in Mr. Fox, “All the happiness had gone from the room, but it never does last very long.”

This Issue

March 7, 2024

Circuit Breakers

‘She Talk Her Mind’

Ready to Rumble