Known today as a writer of adventure stories for youth (Treasure Island, Kidnapped) or for his horror classic The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, or even for his light-poetry collection A Child’s Garden of Verses, in his day Robert Louis Stevenson was celebrated equally for his essays. He wrote more than a hundred, of which seventy might be classified as personal. Edmund Gosse argued that these personal essays “reveal him in his best character” and that “if Stevenson is not the most exquisite of the English essayists, we know not to whom that praise is due.” Richard Le Gallienne predicted that “Stevenson’s final fame will be that of an essayist.” Once upon a time his essays were routinely offered as models in American college composition courses. Selections of them—from William Lyon Phelps’s Essays of Robert Louis Stevenson (1906) to The Lantern-Bearers and Other Essays (1988), astutely assembled by Jeremy Treglown—have sought to champion his excellence in the genre.

It has not been an easy sell. In part that may be because essays have never commanded the interest or respect that fiction has, but it may also be because the reading public has resisted relinquishing its settled idea about Stevenson as a romantic fantasist. Now Trenton B. Olsen, an associate professor of English at Brigham Young University, has pulled together the most copious selection so far, reproducing not only Stevenson’s dozen or so celebrated essays but also his uncollected published essays and his undergraduate ones. All this gives us the chance to assess the range and stature of a writer who, according to Olsen, was in his day “considered the most successful essayist of his generation.”

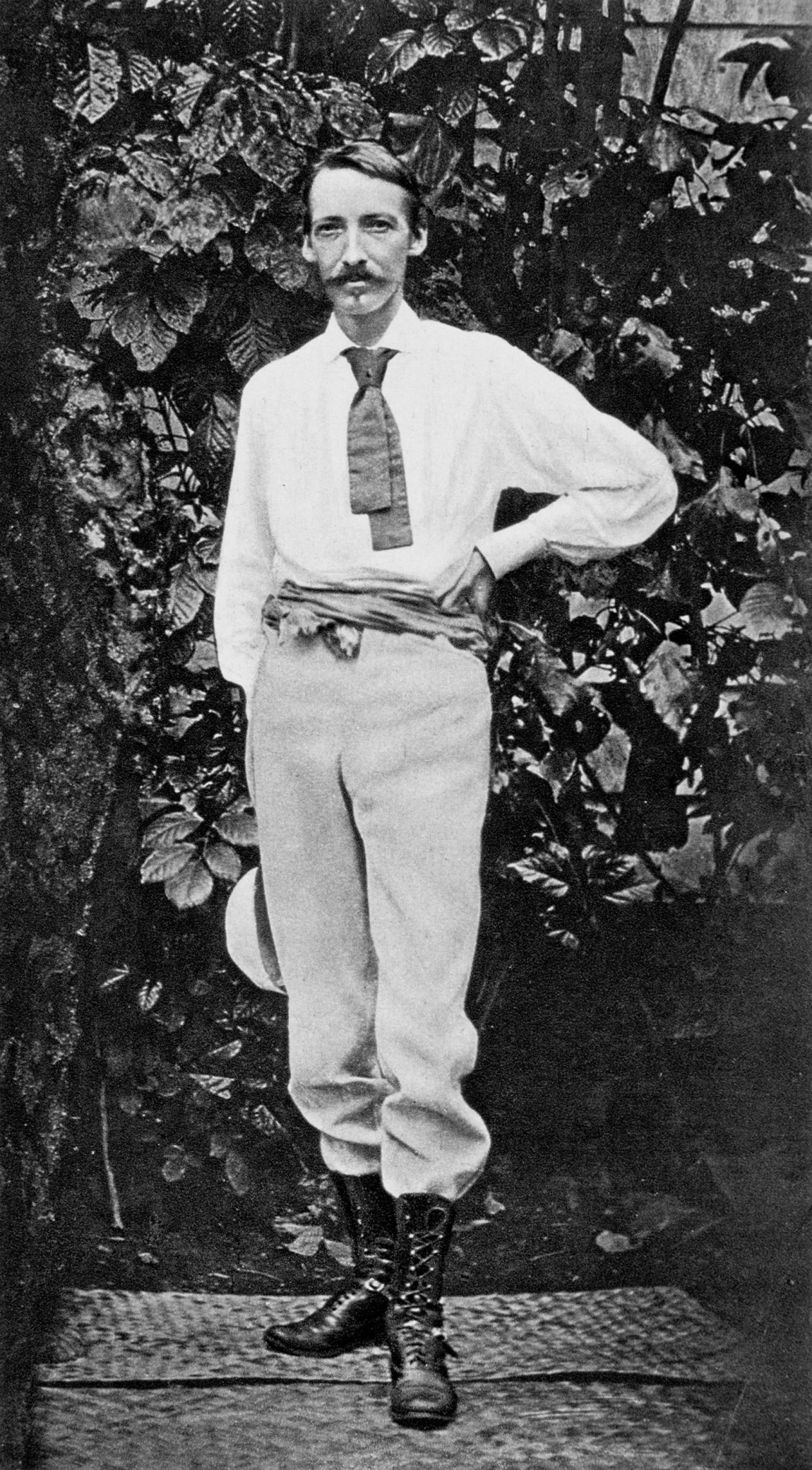

Stevenson was born in 1850 in Edinburgh, Scotland, into a distinguished family of lighthouse engineers. His father, Thomas Stevenson, had invented an ocular device for lighthouses and hoped that his son would go into the family business. But Robert showed little interest in engineering, cutting classes at the University of Edinburgh, and tempered his truancy only when his father coerced him to pursue a law degree instead. In one of his most famous essays, “An Apology for Idlers,” Stevenson cheekily argued for “certain other odds and ends that I came by in the open street while I was playing truant…. Suffice it to say this: if a lad does not learn in the streets, it is because he has no faculty of learning.”

Rebelling against his Scottish Calvinist upbringing, with its narrow emphasis on “respectability” (a word he always wrote with a sneer), and turning away from his family’s religious convictions (to his devout father’s deep sorrow), Stevenson asserted that “there is no duty we so much underrate as the duty of being happy.” He took to dressing bohemian, drinking, and visiting brothels. In fact he was hardly idle, insofar as he spent every available moment trying to master his preferred vocation, literature:

All through my boyhood and youth, I was known and pointed out for the pattern of an idler; and yet I was always busy on my own private end, which was to learn to write. I kept always two books in my pocket, one to read, one to write in. As I walked, my mind was busy fitting what I saw with appropriate words; when I sat by the roadside, I would either read, or a pencil and a penny version-book would be in my hand, to note down the features of the scene or commemorate some halting stanzas. Thus I lived with words. And what I thus wrote was for no ulterior use, it was written consciously for practice.

Such a beautiful description of a young author-to-be’s dedication. But wait, there’s more: “I have thus played the sedulous ape to Hazlitt, to Lamb, to Wordsworth, to Sir Thomas Browne, to Defoe, to Hawthorne, to Montaigne, to Baudelaire, and to Obermann.” (Notice the proliferation of personal essayists in his list of models.) He catches himself—“I hear some one cry out: But this is not the way to be original!”—then declares that imitation is the royal road to originality, citing Montaigne’s drawing on Cicero. “It is only from a school,” Stevenson says, “that we can expect to have good writers.”

At a time when the English essay had gravitated toward the more formal, intellectual, stately prose of Thomas Carlyle, Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin, and Walter Pater, Stevenson chose to attach himself to the older, more informal school of William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb. He took up many of the personal essay’s standard themes, such as friendship, talk, walking around, elderly relations, childhood, the past, and everyday objects. (See his playful essay “The Philosophy of Umbrellas.”) He was particularly enamored of Hazlitt, insisting that “though we are mighty fine fellows nowadays, we cannot write like Hazlitt.” In his essay “Walking Tours” he cited Hazlitt’s “On Going a Journey” as being “so good that there should be a tax levied on all who have not read it.”

Advertisement

Stevenson’s own essays are more genial than those of the combative, truculent Hazlitt, but he took from the older writer a liking for energetic, rhythmic prose. He even toyed with the idea of writing a biography of Hazlitt, then gave up the project in dismay when he came across Liber Amoris, the astonishingly frank account Hazlitt wrote of his unrequited infatuation with an innkeeper’s daughter. (There was a prim, Victorian avoidance of sex in Stevenson’s writing, despite his appetite for experience.)

One motivation that kept him seeking adventures was his ill health, a pulmonary weakness he had suffered ever since he was a boy. Few writers have been as consistently aware of encroaching mortality as Stevenson, and he tried to cheat death or at least stay one step ahead of it, cramming as much living as he could into his brief forty-four years. “It is better to lose health like a spendthrift than to waste it like a miser,” he wrote. As the biographer-critic Treglown succinctly put it:

He had always wanted to escape from the certitudes and complacencies, religious, moral and social, of his Edinburgh upbringing, and had been helped in doing so by the travelling his poor health necessitated. Visits to foreign spas were not only desirable, but required.

The title of one essay, “Ordered South,” says it all.

He wrote about hanging out with the Barbizon painters in Fontainebleau, exploring the mountains around the sanatorium in Davos, frequenting the Latin Quarter in Paris. He freely dispensed advice about the art of life—polemics that must be read as reflections of a semi-invalid for whom existence itself was never to be taken for granted. His Thoreauvian preference for enjoying the outdoors instead of being buried in an office can get annoying, especially to those of us who must submit to the daily grind because we haven’t had the advantage of parents who foot the bills. He admitted that his privilege often made him uneasy. Referring to himself in the third person, he wrote:

Some time after this, falling into ill health, he was sent at great expense to a more favourable climate; and then I think his perplexities were thickest. When he thought of all the other young men of singular promise, upright, good, the prop of families, who must remain at home to die and with all their possibilities be lost to life and mankind; and how he, by one more unmerited favour, was chosen out from all these others to survive; he felt as if there were no life, no labour, no devotion of soul and body, that could repay and justify these partialities.

As a young man Stevenson even declared himself a socialist, and though he gave up that political affiliation, he continued to brood about the fate of the poor. In time he would join them, reluctant to keep accepting money from his father and forced to eke out an impecunious living with freelance newspaper pieces. He was especially hard up on his travels through the United States. Having idealized America as a land of democracy and egalitarianism, greatly admiring Whitman’s brief for the common man, in 1879 he set off ill-advisedly across the continent only to have his illusions uprooted by the cupidity he encountered, arriving in San Francisco an emaciated scarecrow. (The trip is described sardonically in his book-length account, The Amateur Emigrant.)

He was crossing the United States to join his intended fiancée, Fanny Osbourne, with whom he had fallen in love on earlier travels. Osbourne was American, ten years his senior, the mother of three children (one of whom had died from tuberculosis), and soon to be divorced from her philandering husband. When they married in 1880, Stevenson found himself the head of a household with steep financial responsibilities, and he could no longer play at being a young man on the loose. In a deliciously witty essay, “A Letter to a Young Gentleman Who Proposes to Embrace the Career of Art,” he warned, “Weed your mind at the outset of all desire of money…. If a man be not frugal, he has no business in the arts.”

His altered domestic situation inevitably affected the subjects of his essays. In a series titled “Virginibus Puerisque,” he wrote trenchantly about women, love, and wedlock. Taking issue with Victorians putting women on a pedestal, he wrote:

That doctrine of the excellence of women, however chivalrous, is cowardly as well as false. It is better to face the fact, and know, when you marry, that you take into your life a creature of equal, if of unlike, frailties; whose weak human heart beats no more tunefully than yours.

Stevenson biographers are divided between those who regard Osbourne as a saintly supporter of the writer and those who claim that her hypochondria, hostility to some of his friends, and mental breakdowns made for endless complications. Regardless, the flowering of Stevenson’s fiction-writing gifts seemed to depend on the stability of his marriage.

Advertisement

A family man, by 1883 he had finally succeeded in becoming a popular novelist. As he stated with rueful candor in his essay “My First Book: Treasure Island”:

It was far indeed from being my first book, for I am not a novelist alone. But I am well aware that my paymaster, the Great Public, regards what else I have written with indifference, if not aversion…. I was thirty-one. By that time, I had written little books and little essays and short stories; and had got patted on the back and paid for them—though not enough to live upon.

That changed with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which made him world-famous. For this classic tale of the divided self, Stevenson claimed in his essay “A Chapter on Dreams,” he drew on the forces of the unconscious, which he called “the Brownies” (a Scottish term for a household fairy):

That part which is done while I am sleeping is the Brownies’ part beyond contention; but that which is done when I am up and about is by no means necessarily mine, since all goes to show the Brownies have a hand in it even then.

Might not the two halves of his sensibility also be seen as representing the fiction writer, exploring half-hidden impulses of desire, and the more rational-sounding essayist?

In the meantime, his essays had deepened and grown more complex. “The Lantern-Bearers” (1888), arguably his greatest essay, begins with a recollection of the “easterly fisher village” where Stevenson spent his vacations as a child:

The place was created seemingly on purpose for the diversion of young gentlemen. A street or two of houses, mostly red and many of them tiled; a number of fine trees clustered about the manse and the kirkyard, and turning the chief street into a shady alley; many little gardens more than usually bright with flowers; nets a-drying, and fisher-wives scolding in the backward parts; a smell of fish, a genial smell of seaweed; whiffs of blowing sand at the street-corners; shops with golf-balls and bottled lollipops; another shop with penny pickwicks (that remarkable cigar) and the London Journal, dear to me for its startling pictures, and a few novels, dear for their suggestive names: such, as well as memory serves me, were the ingredients of the town.

This leisurely opening showcases the finesse of a novelist, employing all five senses. The description of the village continues in rich detail, summoning the pleasures of memory, until, suddenly, we get a jolt, issuing from the gothic side of Stevenson:

There are mingled some dismal memories with so many that were joyous. Of the fisher-wife, for instance, who had cut her throat at Canty Bay; and of how I ran with the other children to the top of the Quadrant, and beheld a posse of silent people escorting a cart, and on the cart, bound in a chair, her throat bandaged, and the bandage all bloody—horror!—the fisher-wife herself, who continued thenceforth to hag-ride my thoughts, and even today (as I recall the scene) darkens daylight.

But all this is preamble: “What my memory dwells upon the most, I have been all this while withholding.” It was the boys’ felicitous practice of carrying lanterns hidden inside their coats:

The essence of this bliss was to walk by yourself in the black night, the slide shut, the top-coat buttoned; not a ray escaping, whether to conduct your footsteps or to make your glory public: a mere pillar of darkness in the dark; and all the while, deep down in the privacy of your fool’s heart, to know you had a bull’s-eye at your belt, and to exult and sing over the knowledge.

Stevenson is here on comfortable ground, celebrating with fondness the knightly bravery of boyhood.

From there he makes a radical shift as he contemplates various adult figures like the miser, whose outward form seems wretched but whose inner life may be teeming with secret joy, or others

who are meat salesmen to the external eye, and possibly to themselves are Shakespeares, Napoleons, or Beethovens; who have not one virtue to rub against another in the field of active life, and yet perhaps, in the life of contemplation, sit with the saints.

The hidden lantern is metaphorically transferred to the inner life of seemingly nondescript citizens, whose imaginative resources we would do well not to misjudge or dismiss too quickly.

Then it is but a brief step to Stevenson’s attack on the realist school of fiction writers, led by Émile Zola, with its emphasis on “cheap desires and cheap fears,” on “that meat market of middle-aged sensuality” and “on life’s dulness and man’s meanness,” which to his mind is “a loud profession of incompetence.” For “the true realism, always and everywhere, is that of the poets: to find out where joy resides, and give it a voice far beyond singing.”

One needn’t agree about Zola to admire the panache with which Stevenson protects a space for the imagination, for dreaming and innocence, associated, characteristically for him, with boyhood. The author of such swashbuckling tales as The Master of Ballantrae and The Black Arrow was defending not only his own work but the whole Romantic school of novelists, and fantasy in general. In his essay “A Humble Remonstrance,” Stevenson took exception to Henry James’s insistence that fiction must draw its inspiration from life, saying that life was too ragged, complicated, and random to serve as a proper model for literary art.

“For to miss the joy is to miss all,” asserts “The Lantern-Bearers.” Stevenson traveled the world over, looking for experiences that might offer him alternatives to his Edinburgh upbringing. He remained intensely loyal, though, to Scottish history, dreaming up plots about the courage of his ancestors. In the end he and his wife and stepson, Lloyd, settled in Samoa, the final destination in his quest for health. He built an estate there, Vailima, and became a revered member of the community, who called him the Writer of Stories. He gathered folktales and took historical and anthropological notes, which were published in newspaper accounts during his lifetime and ultimately gathered in his engrossing posthumous book In the South Seas. He who had once declared it the mission of the writer “to protect the oppressed and to defend the truth” wrote an impassioned brief for the islanders, A Footnote to History, which castigated the colonial powers—England, France, the United States, and Germany—for exploiting them and destroying their way of life.

It is customary for literary critics to argue that Stevenson, in his Samoan years, turned away from the writing of romances and converted to realism. Certainly he needed specific facts to bolster his descriptions of the islanders, especially as he was writing a sympathetic account on their behalf. And his last fictional effort, Weir of Hermiston, which remained unfinished at the time of his death of a brain hemorrhage in 1894, does seem closer than he ever came to psychological realism. On the other hand, the many essays he had been writing for years had trained him in a flexible style that could well be considered realistic, regardless of their defense of Romanticism.

What are we to make, finally, of his contribution to the essay form and of the popular neglect of that body of work? Stevenson, worshiping at the altar of literature, polished every word and page in his essays. His Victorian prose style is highly wrought and impeccably smooth, with long, elegantly turned sentences embedded in lengthy paragraphs, and a sprinkling of Latin, all of which dates him, alas. He was much admired by Henry James and Joseph Conrad, and Jorge Luis Borges considered him one of the masters of English prose. Though Max Beerbohm greatly admired his stories, he found Stevenson’s essayistic prose “too much given to manner in literature” and “over-fond of unusual words and peculiar cadences.”

In his day, despite Beerbohm’s objection, Stevenson was the most user-friendly of writers, but his packed paragraphs require a diligent attentiveness that contemporary readers, fed on shorter, more direct sentences, may find taxing. Under Ruskin’s influence, he wrote knowingly enough about flora and fauna to qualify as a nature writer, though sometimes he would overdo the landscape descriptions. He himself noted, “No human being ever spoke of scenery for above two minutes at a time, which makes me suspect we hear too much of it in literature.”

However we might choose to rate him, we can situate him as the bridge between the early-nineteenth-century giants, Lamb and Hazlitt, and later practitioners of the personal essay such as Beerbohm, Virginia Woolf, G.K. Chesterton, and George Orwell. His sensibility is not skeptically protomodernist, like Montaigne’s; he is solidly old-school, with a sweetness, kindness, charity, wisdom, and tact that must be appreciated for what they are.

Every writer, Stevenson said, “should recognise from the first that he has only one tool in his workshop, and that tool is sympathy.” He exercised his powers of sympathy and detachment extensively in his literary criticism, and it is a pity that some of these essays, like “A Humble Remonstrance” and “The Gospel According to Walt Whitman” (one of the best things ever written about the poet), could not be included in Olsen’s collection, as they were not deemed personal essays. Having championed the personal essay as a distinct subgenre in years past, I have come to appreciate just how blurry is the line between personal and critical essays: Woolf, Orwell, Beerbohm, James Baldwin, and Susan Sontag, as well as Stevenson, all wrote both, and their personalities shone as brightly in one form as in the other. Were a complete volume of his critical essays put together, we would be even better positioned to evaluate Stevenson.

As for the “personal” part of the equation, Stevenson, though keenly self-aware, did not seem particularly inclined to reveal his neurotic quirks and eccentricities the way Lamb or Hazlitt did. We learn the rudiments of his life story from his essays, but there is a sense of propriety that forbids further intimacy. Besides, the invalid existence he led made him more curious about the people he met than about himself; many of his essays are portraits of others. “It is salutary,” he wrote in his essay “An Autumn Effect,” “to get out of ourselves, and see people living together in perfect unconsciousness of our existence, as they will live when we are gone.”

The figure he cuts in these essays is that of a sane, intelligent, compassionate, observant, and good-humored man, eager to act morally but unsure that he will ever be able to. He thought a proper epitaph should read, “Here lies one who meant well, tried a little, failed much.” Essays as a general rule are exploratory and do not invite perfection, but his humble assertion should be balanced by the statement of The Cambridge History of English Literature (1916) that he was “the foremost essayist since Lamb.” In any case let us be grateful for Olsen’s collection, which offers more than enough evidence of this profoundly likable practitioner’s achievements in the essay form.

This Issue

April 4, 2024

Mourning Navalny

Sisyphus on the Street

The Way She Was