More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

David Shulman is the author of Tamil: A Biography, among other books. He is a Professor Emeritus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and was awarded the Israel Prize for Religious Studies in 2016. He is a longtime activist with Ta’ayush, the Arab–Jewish Partnership, in the occupied Palestinian territories. (May 2024)

Heading Toward a Second Nakba

Nathan Thrall argues that the accident in which Abed Salama’s son died was a predictable, even inevitable, outcome of the Israeli occupation in its quotidian forms.

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy

by Nathan Thrall

October 19, 2023 issue

Cosmic Oceans Squeezed into Atoms

The idiosyncratic wisdom of the Tirukkural’s poetry is about aliveness, perhaps the most elusive of human goals.

The Kural: Tiruvalluvar’s Tirukkural

translated from the Tamil by Thomas Hitoshi Pruiksma

October 6, 2022 issue

Lost Illusions

Sylvain Cypel's transformation from liberal Zionist to ferocious critic of Israel.

The State of Israel vs. the Jews

by Sylvain Cypel, translated from the French by William Rodarmor

February 10, 2022 issue

The Widows’ Laments

Until the Lions: Echoes from the Mahabharata

by Karthika Naïr

September 24, 2020 issue

Buddhist Baedekers

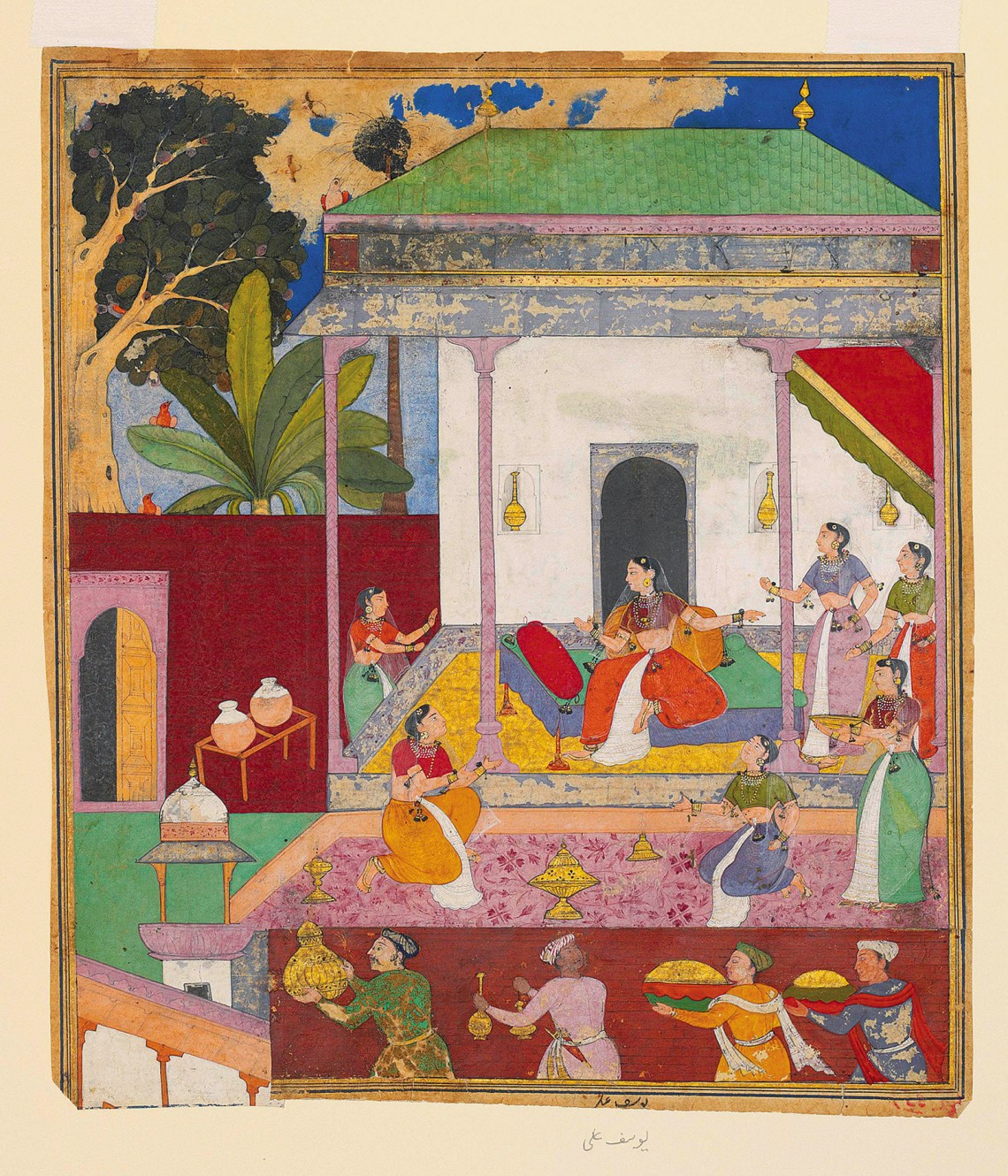

Creating the Universe: Depictions of the Cosmos in Himalayan Buddhism

by Eric Huntington

Awaken: A Tibetan Buddhist Journey Toward Enlightenment

an exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, April 27–August 18, 2019; and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, January 17–April 19, 2020

March 26, 2020 issue

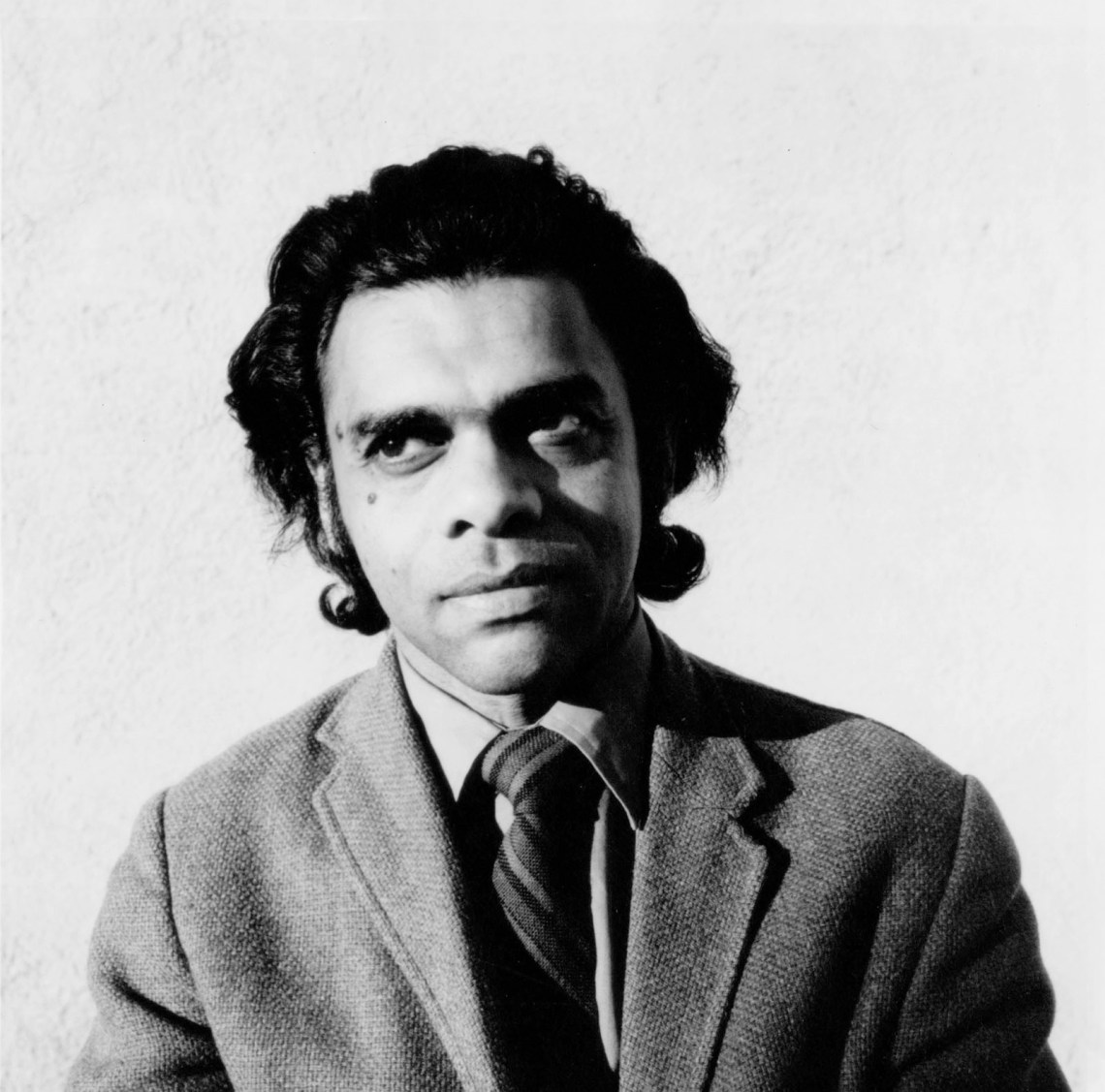

Waiting for the Perfect Word

Journeys: A Poet’s Diary

by A.K. Ramanujan, edited by Krishna Ramanujan and Guillermo Rodríguez

The Interior Landscape: Classical Tamil Love Poems

edited and translated from the Tamil by A.K. Ramanujan

September 26, 2019 issue

The Last of the Tzaddiks

What is a decent human being supposed to do in the face of devastating threats to human dignity and basic human rights?

Rooted Cosmopolitans: Jews and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century

by James Loeffler

The Wall and the Gate: Israel, Palestine, and the Legal Battle for Human Rights

by Michael Sfard, translated from the Hebrew by Maya Johnston

June 28, 2018 issue

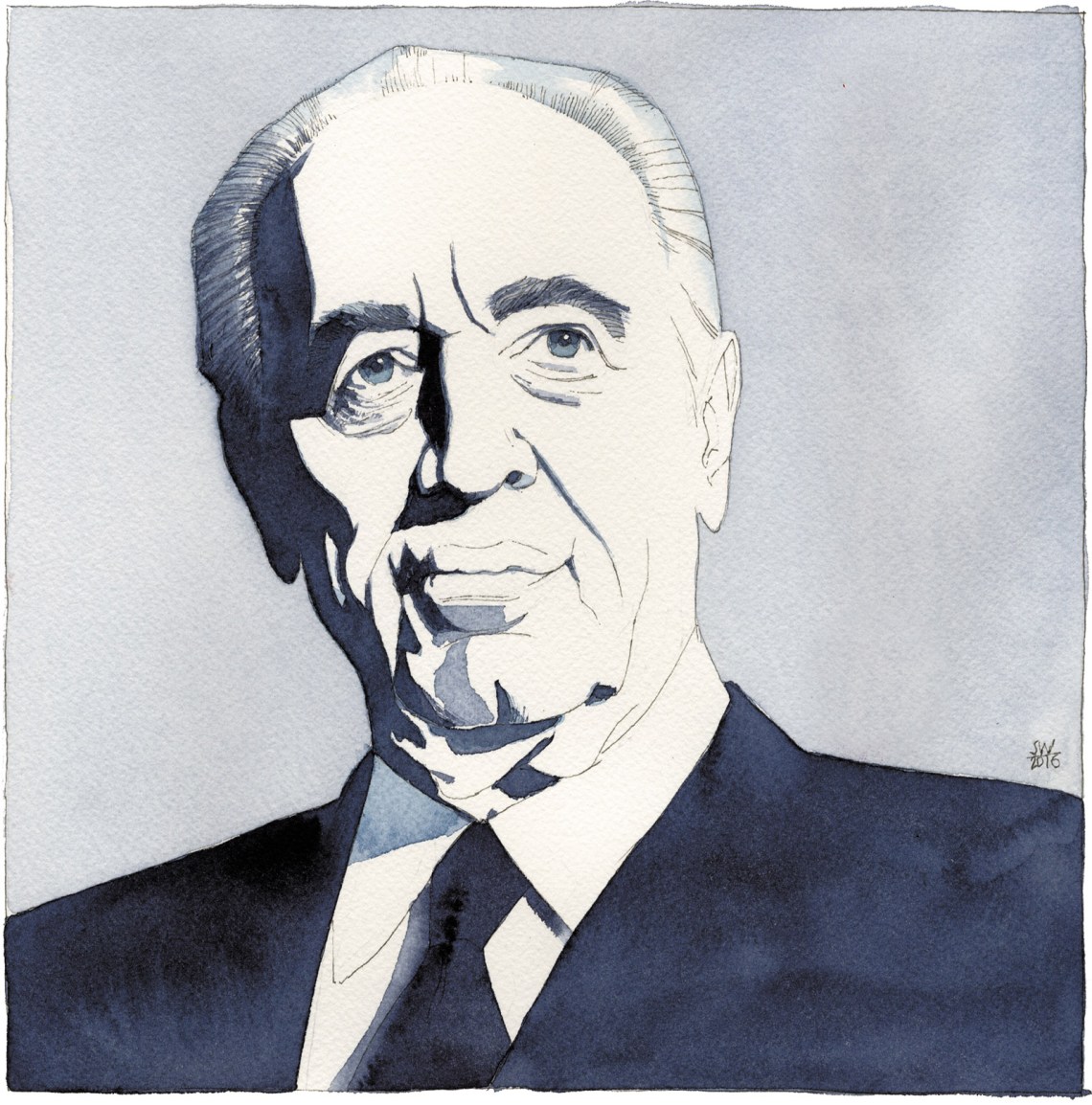

A Hero in His Own Words

Shimon Peres’s ‘No Room for Small Dreams: Courage, Imagination, and the Making of Modern Israel’

No Room for Small Dreams: Courage, Imagination, and the Making of Modern Israel

by Shimon Peres

December 7, 2017 issue

Israel’s Irrational Rationality

The country I came to live in fifty years ago was utterly unlike the one I live in today.

The Six-Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East

by Guy Laron

The Only Language They Understand: Forcing Compromise in Israel and Palestine

by Nathan Thrall

In Search of Modern Palestinian Nationhood

by Matti Steinberg

Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation

edited by Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman

A Half Century of Occupation: Israel, Palestine, and the World’s Most Intractable Conflict

by Gershon Shafir

June 22, 2017 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Read the latest issue as soon as it’s available, and browse our rich archives. You'll have immediate subscriber-only access to over 1,200 issues and 25,000 articles published since 1963.

Subscribe now

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in