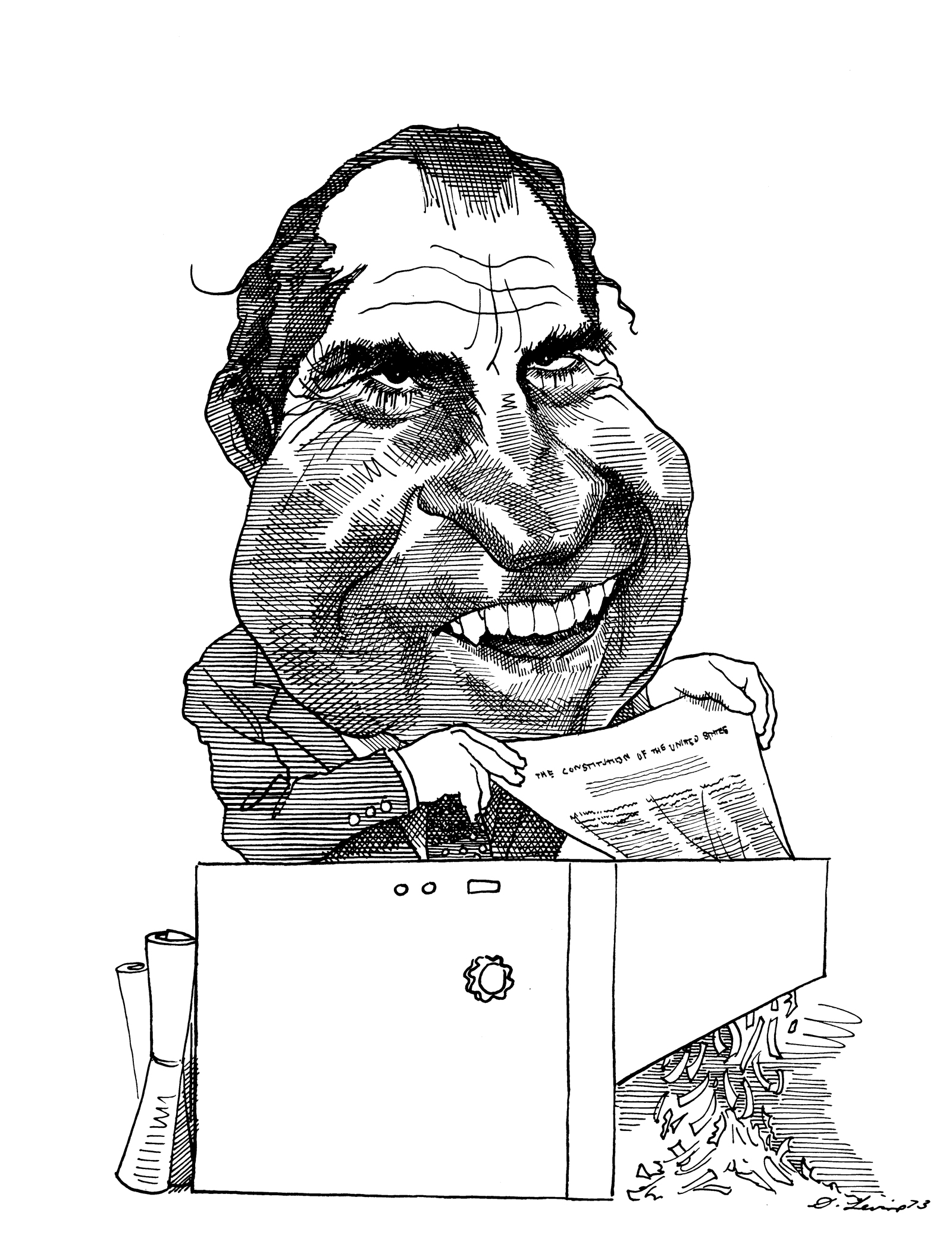

Early in the summer, as the news from the White House grew to be ever more Twilight Zone-strange, it seemed as though an interview with John W. Dean III might be timely. After all, Dean—once Richard M. Nixon’s White House Counsel—is the great expert on presidential misconduct and its consequences. It was his whistleblowing to the Senate Watergate Committee in June 1973 that helped to precipitate the process that led ultimately to Nixon’s August 1974 resignation. What is similar? What is different?

Today, Dean, who is seventy-nine and lives in Beverly Hills, writes books about history and politics. His eleventh and most recent title, The Nixon Defense, appeared in 2014. This week, though, Dean returns to Washington, D.C., where he will be testifying at the confirmation hearings of Brett Kavanaugh, President Trump’s nominee for the US Supreme Court. One of the issues under senatorial scrutiny will, no doubt, be that Kavanaugh once questioned whether the Supreme Court should have forced Nixon to relinquish those secretly recorded White House tapes.

John Dean and I spoke three times by telephone in August for a total of more than three hours. The repeat calls were necessary as news kept breaking—Michael Cohen copping a guilty plea, Donald Trump dubbing Dean a “rat,” the current White House Counsel, Donald McGahn, getting fired by tweet.

“You’re never going to get ahead of this story,” Dean admonished me after another request for yet another update. He’d know.

An edited and condensed version of our conversations follows.

—Claudia Dreifus

Claudia Dreifus: Have you, as a veteran of Watergate, been watching the evening news and thinking, as Yogi Berra once said, “It’s déjà vu all over again?”

John Dean: Well, I’m not one of those people who believes that history repeats itself. But we do see parallels and similarities in the processes that are unfolding. How it will end, I don’t have a clue.

Do I believe that Trump’s in a whole world of trouble? I do! Do I think Trump will resign? Not likely! And unlike Nixon, who honored the rule of law and actually in his bones believed in it, I think Trump is the kind of guy who would do anything to get around the rule of law.

He’s spent his entire life trying to avoid responsibility, and he’ll do the same here.

How would you compare the personalities of Trump and Nixon?

They are both authoritarians. They have that in common. Nixon was an authoritarian behind closed doors. Trump is authoritarian both behind closed doors and on the public stage.

Trump has lately been tweeting about you. On August 19, he called you a “rat.”

Listen, he takes cheap shots at everybody. I’m just the cheap shot at the moment. I feel honored to be in his pejorative invective club.

Who knows what he’s really talking about? I suspect he has minimal, if any, knowledge of Watergate. This is a man who knows virtually no history. I don’t think he’s aware that before going to the prosecutors, I had informed Nixon, through John Erlichman and H.R. Haldeman exactly what I would be doing there. And there’s a tape where Ehrlichman, the assistant to the president for domestic affairs, reports to Nixon on my session. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, called me from Air Force One the night before my meeting with prosecutors to remind me, “Once the toothpaste is out of the tube, it’s very difficult to get it back in.”

I was very open with my colleagues about what I was talking to prosecutors about. I kept encouraging them to go to the prosecutor, too. I said, “We have to end the cover-up.” I thought, the way to end the cover up was at the grand jury. I told my lawyer, “My desire is not to beat the rap. I’m prepared to take whatever the consequences.”

Trump’s tweet about you came in reaction to a New York Times story reporting that Trump’s White House Counsel, Donald McGahn, had been interviewed by Robert Mueller at least three times for a total of thirty hours. The story hinted that McGahn might be concerned that Trump’s people want to make him the fall guy in the current investigation. Does that scenario sound familiar to you?

You know, one of the things that Watergate did was change our understanding of who the client of the White House Counsel is.

When I was there, Nixon thought I was his lawyer. He had me working on such things as coordinating between an East Coast firm and a West Coast firm working on his estate plan, which is about as personal as you can get. That was resolved post-Watergate. Under today’s practice, the client of the White House Counsel is not the president, but rather the Office of the President.

Advertisement

That gives McGahn a lot of leverage I didn’t have. The White House Counsel represents the entity of the Office of the President and not the occupant. And there, there can be conflicts between the two. I’m sure that McGahn and his team know where the danger areas are.

For example, after Trump wanted him to get Sessions to reverse his recusal from the Russia investigation, McGahn refused because he was worried he [the president] would be obstructing justice. That was an absolutely correct thing to be worried about. Today, they are much more aware of these things because of what happened during Watergate, when we learned about these laws the hard way.

There have been reports that people in Trump’s inner circle—perhaps the president himself—were annoyed because they have no idea what McGahn said to Mueller.

I don’t think they have a clue what McGahn talked about. My reading between the lines of that reporting indicates that it was pretty contemporaneous information that he was giving. I think McGahn’s own lawyer, a very savvy criminal defense lawyer, saw talking to Mueller as a clear chance to make his client a witness and not a target of the investigation.

Moreover, it’s interesting that McGahn’s lawyer later said they gave the prosecutors nothing implicating the president. Well, if McGahn was worried he was going to be implicated, it would strike me that McGahn was giving information that could implicate others.

What about Michael Cohen? Many of the pundits are casting Trump’s former lawyer as “the new John Dean.” What advice would the old John Dean give him?

Well, I have no idea what Michael Cohen has or has not done. He’s pleaded guilty to bank fraud, and I think there was tax fraud, as well. Then, of course, there’s the Federal Election Campaign Act violation in paying the hush money to at least two people whom Trump wanted to silence before the election. I’ve seen reports that suggest there are more women involved that Michael Cohen might have more information about.

Now, I have talked to his lawyer, Lanny Davis, an old friend. Lanny knows Watergate pretty well and saw certain parallels between his client’s situation and mine. I was happy to share with Lanny information to refresh his recollection about those times.

I sense that Cohen has a fair amount of corroboration on what he’s saying about the president. If it hadn’t been for Nixon taping himself, I might not have had corroboration.

The turning point in Watergate was the discovery of the tapes by the Senate Watergate Committee. One of the minority staff members asked Alexander Butterfield, the deputy assistant to Richard Nixon, a question to discredit my testimony. It went something like, “Mr. Dean claims he was taped. Now that’s not possible, is it?” And Butterfield confirmed that it was very possible.

Back to Michael Cohen and the discovery that he’s taped his client numerous times. If that’s what people see as a parallel between us, they are wrong. I didn’t tape anyone. But maybe Trump taped Cohen? We’ll have to see how this plays out.

In the weeks before Cohen entered his guilty plea, he appeared to be desperately signaling Trump, as if to say, “I really don’t want to do this. Please, help me out!”

Nobody wants to blow the whistle! In our culture, from pre-school on, tattle-tales are not the most respected people.

The way I handled it with my colleagues was that I tried to get them to do the right thing. I told them what I was going to do. I was still working at the White House at that point and they were pushing me to write a bogus report. I said, “I’m not going to do that. I’m going to get myself a good criminal lawyer. I recommend that you guys do the same.”

In the end, I didn’t have a problem with blowing the whistle because they were setting me up. They’d decided they’d make John Mitchell responsible for the break-in and me the scapegoat for the cover-up.

One of the interesting things Nixon said in his memoir about my testimony is that he wasn’t particularly worried about my knowledge of his Watergate-related activities. That’s probably fairly accurate because I didn’t deal with Nixon until eight months after the arrests at the Watergate. Nixon wasn’t as worried about what I knew about the break-in, but what I’d picked up in the roughly thousand days I worked at the White House.

Advertisement

I came to know about an awful lot of activities that were unsavory—like the “Enemies List” and a plan to fire-bomb the Brookings Institution and break into the place to get documents Nixon wanted. When I testified before the Senate Watergate Committee. I tried to put these things into a context to show how Watergate could occur.

If Michael Cohen can put Trump into a larger context of “that’s how they do business,” he can probably have a similar impact.

Are the current president’s legal problems similar to those leading to Richard Nixon’s resignation?

I see some differences. The most conspicuous is that Nixon knew what he was doing. Trump does not. It makes a difference on criminal intent.

Nixon was, for example, very aware of the law relating to perjury. He had made his bones as a young congressman, convicting Alger Hiss of perjury. Nixon coached and encouraged perjury, knowing exactly what he was doing.

Jeb Magruder, the deputy director of [Nixon’s] re-election campaign, had to perjure himself to make the cover-up succeed. There’s a tape in which Nixon called Magruder the night before his [Magruder’s] grand jury testimony to give him a sort of booster. I doubt if Nixon had two telephone calls with Magruder during his presidency.

One of the criminal issues that Mueller may be investigating is whether or not Trump has consciously and deliberately engaged in an obstruction of justice. Is that another Watergate parallel?

At the White House, none of us had heard of the crime of obstruction of justice. Only people who had worked in big federal prosecutors’ offices, knew anything about that crime. It was a revelation to a lot of us that there was such a crime—and that it wasn’t a bright-line crime where you knew exactly when you’d crossed the line. It very much depended on your intent.

Interestingly, John Ehrlichman, who was convicted of conspiring to obstruct justice, claimed he didn’t commit conspiracy to obstruct justice because he didn’t intend to. The jury didn’t buy that defense.

We might get a similar defense from Trump. He might say, “Well, I didn’t know anything about that. I’m not a criminal lawyer.” However, to conspire to obstruct justice, all you need is a corrupt intention—typically, something you’re consciously aware of.

Now Nixon, he was aware of what he was doing. And he became aware of obstruction of justice because I looked up the statute and explained it to him.

Can you give us an example, based on what you’ve read, of how the obstruction law might apply to Trump?

When Trump assisted in preparing the press release on Air Force One about what happened at the June 9 meeting at Trump Tower, if he intentionally misrepresented what happened there, that’s a corrupt intent. He may not know that from the standpoint of the criminal law, but he doesn’t have to. It’s still a crime.

Would you advise Rudy Giuliani, the president’s lawyer, to study federal conspiracy laws more closely?

Well, Giuliani’s trying to set a narrative. He argues that the jury is going to be the American people because Trump as president can’t be indicted as a sitting president, but he can be impeached. And so that means the representatives of the people are the jury. So Giuliani’s trying to influence the jury.

Is that legal?

It is.

You were thirty-one years old when you left the Justice Department to become the White House Counsel. Did you suspect then that this move would follow and shape the rest of your life?

I never thought that Watergate would follow me my entire life. There were a few years right afterward when I went out and lectured about it. Then I stopped. People like yourself would call and ask me to comment on a presidential scandal. Mostly, I refused. I didn’t want anything to do with Watergate.

Eventually, I went into business. I went back to school and studied accounting, and did mergers and acquisition with a couple partners. We had some real success. The only reason I got back into Watergate was when my wife and I filed a lawsuit against the authors of a revisionist book about Watergate. Because of our lawsuit, I became something of a student of Watergate, looking at material I had never examined.

Early on, in 1977, I wrote a book about my experiences in the Nixon White House, Blind Ambition. Right now, I’m beginning to consider starting a final accounting of all I have learned about Watergate—something like Watergate at Fifty.

When historians look at Watergate, they often say that the scandal proved the strength of the American system. Today, many see the current crisis as proof of the system’s fragility. What’s your view?

The system is slow. That’s what people are unhappy with. We’re still working on Trump. It’s early. And it takes time for the public to comprehend what is happening.

Also, there is no equivalent today of the Senate Watergate Committee, whose members thought it important to inform the Congress and the public as to what was happening in the Nixon presidency. Today, we have the House Intelligence Committee, which the Republicans made sure was a whitewash; the House hasn’t made any effort at all to understand what was going on. On the contrary, they’ve tried to hinder the investigation.

The Senate Intelligence Committee seems to be more bipartisan and is trying to understand the problems. But it has not reported publicly and, in all likelihood, will not. All of that could change after the November election, if there’s a different Congress.

With time, I believe we will learn what Trump has or has not done with the Russians, who clearly played a subversive role in the 2016 presidential election.

The end for Nixon came in the summer of 1974 when a group of influential Republicans went to the White House and told the president it was over. Despite the Russia stuff, current-day Republicans seem to be bent on protecting Trump. What’s changed?

I hear a lot of people say, “the Republicans stood up to Nixon during Watergate and they’re not doing anything to check Trump.” Those who say that don’t really know much about Watergate because it wasn’t until the very, very, very end that the Republicans in serious numbers turned against Nixon—as did the Democratic Party. And that was the moderate Republicans.

The Republican Party of 1972 to 1974 was much different to the Republican party today. It ran from progressive to moderate to conservative—as did the Democratic party. Both parties then were “big tent.” It’s hard to compare the parties because they are, today, different entities.

Here’s a question I’ve waited almost half a century to ask: When you were testifying before the Senate Watergate Committee, were you frightened? You were young, in your early thirties, and your future, as well as that of the Republic, depended on your believability. The weight of that must have been terrifying.

I’m not somebody who gets easily rattled. Having worked as a committee counsel for the House Judiciary Committee, I was very comfortable in a congressional forum.

Of course, it was my word against Nixon’s—and Nixon went on television and said, “Dean is lying.” But when, a month after my testimony, Alexander Butterfield testified that Nixon had been taping himself, I knew the game was over. I knew how it was going to all turn out.

Were you astonished to learn of existence of the tapes?

I thought that Nixon might have had something he could turn on and off to record selected conversations. But I never dreamed he’d have a voice-activated system that would automatically record whenever he was in the room.

And having transcribed hundreds of hours of those tapes for my last book, I realize that Nixon clearly forgets that he is taping. The person who was most aware is H.R. Haldeman. Haldeman is careful, most of the time.

Earlier, when my taping equipment malfunctioned, I asked—with some hope—whether you might be recording our conversation. You’ve told me that you never tape telephone calls. I’m wondering if your experience with Nixon made you reluctant to do that?

I don’t have any inclination to secretly tape-record people. I believe it is dishonest. Actually, I was thankful for Nixon’s taping. I bless him for making those tapes.

Because the tapes proved the truthfulness of your testimony?

Yes. And what we’ve discovered over the last forty years, as the tapes have dribbled out, is that things were far worse in the Nixon White House than was thought. There’s information in the released tapes we never knew—like Nixon raising money for the defendants arrested for the Democratic National Committee [break-in] at the Watergate complex. He’s selling ambassadorships. He’s approving key elements of the cover-up.

Nixon did leave a remarkable historical record. We know an awful lot about that presidency because of it. The tapes are one of the reasons that Watergate history has been difficult to screw around with—though Watergate revisionists and Nixon apologists have tried.

No president will ever provide that kind of recorded record again.