Past the faceless concrete housing projects, the kebab joints, the corner stores, the bus stops, and the tramlines of the city of Saint-Denis in metropolitan Grand Paris, the sheep snatch at plants on weedy strips between the sidewalk and the street. Urban shepherdess Julie-Lou Dubreuilh, curly-haired and ruddy-cheeked, dressed in black jeans and a royal-blue down jacket, clicks the end of her long staff on the pavement, urging her flock along with low cries of “ehh.” The sheep quicken their pace, ivy yanked from chain-link fences disappearing into their mouths like strands of spaghetti.

Located just north of Paris, the administrative department of Seine-Saint-Denis is France’s poorest and most ethnically diverse. Its Brutalist public housing complexes, once triumphant monuments to socialist modernism, are now sites of social marginalization. It’s the last place one would imagine seeing wandering shepherds tending their flocks. Yet here, and elsewhere in metropolitan Paris, an urban agricultural revolution is taking root.

That revolution has the blessing of the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo. On her watch, the city pledged in 2016 to cover 250 acres of urban space with greenery by 2020. In 2017, the city launched Parisculteurs, a program that solicits bids for urban agriculture projects to ensure that roughly one third of that area is dedicated to agriculture. One winning project is BienÉlevées, a play on the French expression meaning “well raised” (as in well brought-up children), founded by four sisters who grow saffron on the roof of a Monoprix supermarket.

These are small efforts compared to the intensity of agricultural production in metropolitan Paris’s past when the land traversed by Dubreuilh’s flock today was known as the plaine des Vertus, the Plain of Virtues, its rich soil producing a large variety of food for discriminating Parisians. In 1891, 80 percent of the produce sold at Les Halles, the old food market that was ripped out of the center of Paris in the early 1970s, was grown on the periphery of the city. Some of the plants favored by Dubreuilh’s sheep are survivors from that era. “That,” she said, pointing to what looked to me like a weed on the day I walked with her and her sheep, “is a variety of dandelion that was grown here for salad.”

The agricultural past of peripheral Paris is the jumping off point of the exhibition “Agricultural Capital: Projects for a Cultivated City” at the Pavillon de l’Arsenal, which now runs through February 10. The exhibition’s premise is that the artificial separation of the urban, the agricultural, and the natural in the Île-de-France region has been devastating to all three. As urban space in and around Paris expanded after the end of World War II, so, too, did dedicated space for nature, a tonic urban planners believed essential for city-dwellers. Environmental concerns beginning in the 1970s accelerated a trend of setting aside natural areas as sanctuaries for imperiled wildlife. Agriculture was banished from both the new urban and natural zones. Farmers were stripped of their responsibilities as custodians of an intermingled human and natural environment that produced nourishment for people and created habitat for birds, insects, wild plants, and animals.

Over the past century, exhibition curator Augustin Rosenstiehl told me, “the space reserved for nature in the Île-de-France doubled”—“yet, during the same period, the diversity of our biomass has collapsed.” The key to preserving biodiversity, essential to human survival and to making metropolitan Paris a resilient city, Rosenstiehl believes, is a new urban planning that restores the essential place that small-scale, ecologically sustainable agriculture formerly held in a habitat where people, plants, and animals thrive together.

The exhibition’s 480-page catalog is nothing less than a manifesto—a call to action by an array of architects, urban planners, geographers, agronomists, and farmers who argue that the only way for the metropolitan Paris to survive the environmental calamities and social inequities, including global warming and a sharply divided metropolis that includes some of the richest and many of the poorest people in France, that threaten the city’s future is to embrace “agricultural urbanism.” In his introduction, Rosenstiehl writes: “In the face of ecological crisis, there appears to be a tacit consensus defending the idea of a modern urbanism that goes well beyond the limits of the city to develop all the functions of the region: develop the urban and its activities, but also Agriculture and Nature.” In his remarks at the opening of the Agricultural Capital exhibition in October 2018, Jean-Louis Missika, the deputy mayor of Paris, put the stakes more bluntly, declaring: “The new urbanism will be agricultural or it will not be.”

Advertisement

Whereas “urban agriculture” may include high-tech farm towers, computer-monitored, hydroponically grown tomatoes or micro-irrigated salad beds on supermarket rooftops, “agricultural urbanism” argues for the transformation of the metropolitan into a porous, diverse, interactive habitat where agriculture permeates the experience of the people, plants, and animals that live there—precisely the kind of urban habitat that existed on the periphery of Paris between 1870 and 1930.

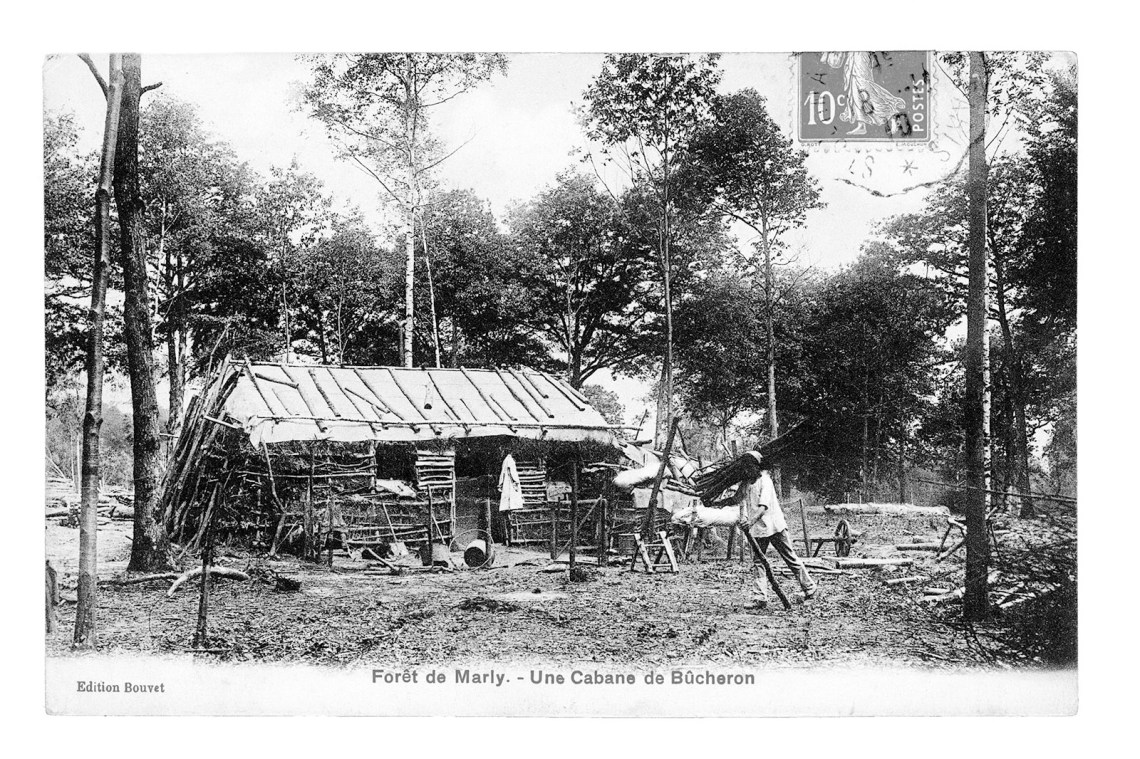

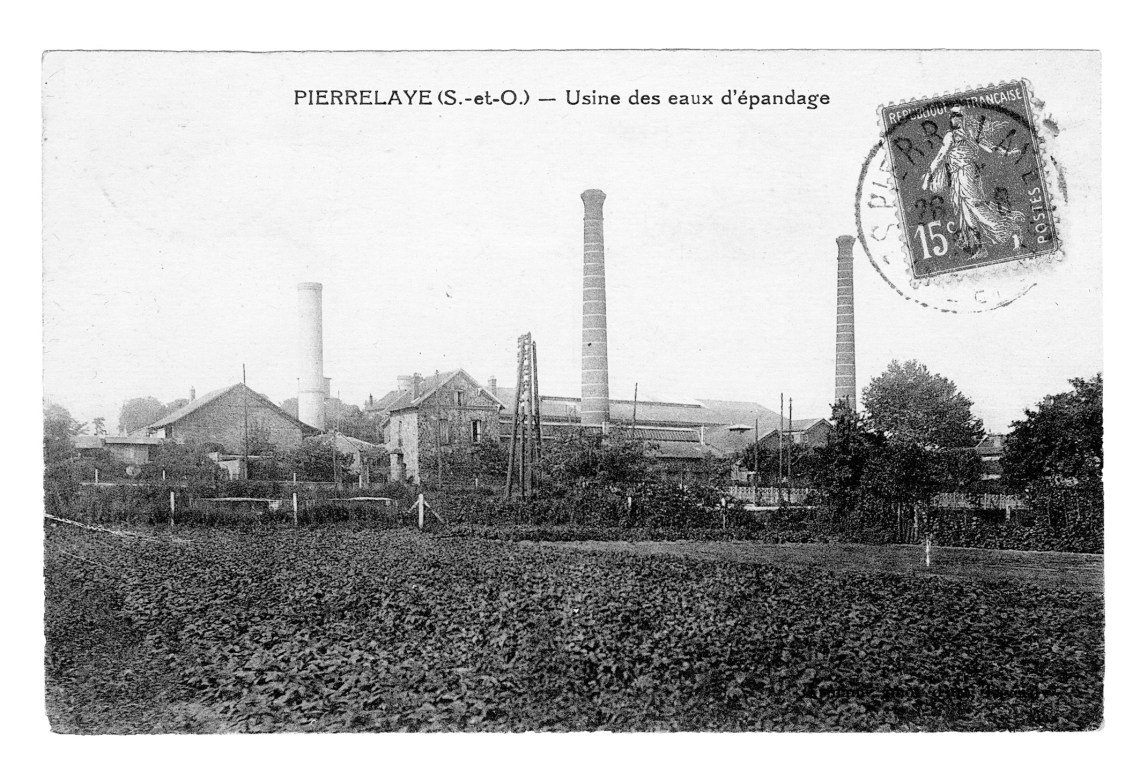

In the nineteenth century, urbanization and industrialization drew from every region of France and countries around the world a cosmopolitan corps of migrant farmers escaping rural poverty. They brought their diverse experiences of farming to land on the outskirts of Paris, making it, the exhibition claims, the most productive fruit and vegetable acreage in history. To meet the demands of hungry Parisians and a bourgeoisie particular about the variety and quality of its food, these farmers, working small plots of land, constantly innovated and improved their production. Without the use of chemical fertilizers or pesticides, they were able, by using techniques such as cultivation under glass cloches, to pull as many as eight harvests a year out of their plots. Carts that took fresh fruits and vegetables into Paris in the morning returned in the evening loaded with manure and other organic waste, which was plowed into the soil. Nearby forests were sustainable sources of wood products. People lived on the land they farmed and were connected to each other and to the city of Paris by a dense network of paths and roads through the cultivated and inhabited land.

This porous, symbiotic relationship between city and country resulted not only in an agricultural productivity superior to what contemporary industrial farming can muster today, but it also did so with little waste or harm to the environment. Food was produced, without chemical inputs, close to where it was consumed. Local pollinators and wild plants and animals found ready habitats in networks of hedgerows and woods. People lived on the land they farmed, in easy proximity to Paris. The farming life was not isolating.

The exhibition labels this period one of “promiscuity,” in the sense of an indeterminate mingling. This promiscuity was wiped away during the second half of the twentieth century by zoning laws that formally separated urban, natural, and agricultural spaces, strictly defining which activities were allowed in each and forbidding, for example, the construction of housing on agricultural land or the grazing of livestock in forests. Small farming plots were consolidated in the service of large-scale, machine-based agriculture. Labor-intensive production of fruits and vegetables disappeared from the riverine valleys around Paris, which became natural corridors for new highways and rail lines, and the development of new urban hubs. In the Île-de-France region around Paris, nearly all the farming that is left is industrial grain production—acre after acre of mono-cropped wheat with nary a person, let alone a bee or bird or animal, in sight.

Using original artwork created for the exhibition, archival photographs, botanical documentation, and comparative maps of land use and population density in the Île-de-France in 1900 versus today, “Agricultural Capital” takes the visitor on a comprehensive tour of more than a century of the evolution of Paris and its environs. It also offers a series of utopian alternatives to urban modernity from the past, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City and Le Corbusier’s Radiant Farm, and references the return of urban agriculture to cities under duress, specifically Havana, Cuba, and Detroit, Michigan. There are large color photographs of some of the urban and suburban farmers who are creating a new “metropolitan rurality” today, and examples of the innovative machinery and technologies they are developing—and sharing on open-source platforms—for urban farming.

Large architectural drawings allow the visitor to envision what a new agricultural urbanism could achieve—say, a highway rest area of the future where people waiting for their electric cars to charge can buy fresh local produce from an adjoining farm, where they can stretch their legs while picking berries along a footpath between the plants. Or the sadly barren lawns surrounding the banlieues’ benighted housing towers replaced with community gardens and a field that turns into a soccer pitch after its safflowers have been harvested. New paths would allow people—as well as wild creatures such as hedgehogs—to circulate between the private gardens of suburban homes, whose standard foundation plantings and chemically dependent lawns have themselves been replaced by edible and pollinator-friendly plants.

The exhibition also imagines Paris’s tramway lines with dedicated trams for livestock, so that flocks like the one shepherded by Dubreuilh could be transported for grazing on public parks and meridians where gas-guzzling mowers and hedge trimmers would no longer be required. Abandoned factories and commercial warehouses could be converted into multi-use structures for performances, housing, food production, and restaurants, as could old barns and hangars for farm machinery, effectively bringing community and the arts to now isolated rural areas.

Advertisement

In late November, I visited one of the urban farming projects featured in “Agricultural Capital.” Located on what was the last remaining vegetable farm in the city of Saint-Denis, the site is a ten-minute walk from the end of the number thirteen Métro line. From the middle of the fields, a McDonald’s is visible on one side of the property. The dome of the Grand Mosque of Saint-Denis rises beyond the other. Rows of multistory apartment blocks flank the back, and more are under construction across from the farm’s entrance. It’s the perfect location for an experiment in agricultural urbanism.

In 2017, a nonprofit artists’ collective, le Parti Poétique, and the for-profit Fermes de Gally jointly signed a twenty-five-year agricultural lease with the city of Saint-Denis, which owns the land. The idea was to create an interactive agricultural space for an ethnically diverse city whose residents have little opportunity to experience farming, and scant access to locally produced food.

Saint-Denis native, artist Olivier Darné, founded the Parti Poétique in 2004 after a beehive he’d set up on the roof of his home led him to think differently about the urban space around him and about the relationship between culture, nature, and food. The honey his bees produced Darné dubbed “Miel Béton,” or concrete honey—“the result of what I call the pollination of the city,” he told me. “Introducing bees was a way to ask questions about how public space functions, not only as a place to send out messages but also as a place to build relationships.”

The Parti Poétique now manages some 120 hives in Saint-Denis, which, the group claims, is the largest urban apiary in Europe. It has also created a bank of fertilized queen bees to populate new hives, a boon to beekeepers and farmers who depend on honeybees to pollinate their crops. Last winter, nearly a third of France’s beehives perished, suspected victims of the pesticides and parasites that have been decimating bee colonies around the world. Metropolitan Paris, where pesticides are little used, has become a “natural” sanctuary for bees facing extinction on industrial farmland.

The new farm is an opportunity for the Parti Poétique to expand its work beyond beekeeping. Called Zone Sensible—the term used by the French state for neighborhoods troubled by disaffected immigrant youth meaning “sensitive area,” but which can also simply mean an area perceptible to the senses—the farm hosts an outdoor performance platform, artists in residence, a kitchen where people from the community can cook using produce and herbs grown on the property, and, of course, beehives.

Standing in the middle of Zone Sensible’s two-and-a-half acre plot on a chilly day this past November, Franck Ponthier, the head gardener for the Parti Poétique, explained as sirens wailed in the distance: “We call this a world garden. There are more than 135 nationalities in Saint-Denis. The goal is to grow, at a minimum, 140 varieties of plants.” A landscaper who had worked with Darné to create bee-friendly plantings in the area, Ponthier gave up landscaping for urban farming in 2016. He said he was disgusted by “seeing soil as rich as gold paved over for parking lots and housing towers.” He is dedicated to establishing an organic farm on the site that uses the techniques of permaculture—the creation of sustainable agricultural ecosystems—in place of conventional single-plant rows vulnerable to pests and disease. To that end, the garden features multitiered, interplanted rows of plants and herbs.

The rows radiate out from a central star with strips of lawn in between, mimicking the formal layout of the Potager du Roi, the kitchen garden created on the orders of Louis the XIV at Versailles. Ponthier told me the layout is in homage to the Fermes de Gally, the Parti Poétique’s partner on the site, which opened its first farm to the public near Versailles. The people of Saint-Denis now have access to a garden befitting a king.

The Fermes de Gally’s La Ferme Ouverte, The Open Farm, occupies a larger portion of the site’s original farm acreage. The Fermes de Gally—operated by the brothers Xavier and Dominique Laureau, whose family has been farming in Île-de-France for a century—now employs some 500 people across France with a mission to “cultivate nature in cities.” In 1967, the Laureaus opened one of the first garden centers in France. In 1995, they created a “teaching farm” in Saint-Cyr-L’École and, a decade later, another in Sartrouville where people could pick their own produce and interact with farm animals.

Xavier Laureau told me the Open Farm “project is atypical because Saint-Denis is atypical.” While the farm’s primary focus is public education, it also aims to create new jobs in urban farming in an area of high unemployment and “to commemorate the type of agriculture that was practiced in the area in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries” as part of a larger mission of the “agricultural reconquest” of urban space. The use in France of the greenhouse effect to heat urban, above-ground agricultural spaces dates back, he said, to the seventeenth century: “We talk about permaculture today but what they did was far more sophisticated.”

At the Open Farm, a former farm building now houses a photographic archive, old farm tools, and indoor hydroponic minitowers. There are spaces where people can bake their own bread and press their own apple juice. There are sheep, goats, and chickens. Rows of vegetables provide produce for a farm stand where several women in headscarves were buying produce on the day I visited. “We had no place to buy fresh vegetables like this before,” one told me. An old hangar next to the original farmhouse is slated to be converted into a multi-use space for concerts, lectures, meetings, and other public events.

Laureau contributed essays to the “Agricultural Capital” exhibition catalogue and in November spoke at a public meeting on urban agriculture in Paris that was organized by Enlarge Your Paris, the Métropole du Grand Paris, and the Bergers Urbains, the urban shepherds, including Dubreilh, who founded Clinamen, their sheep operation. The event, part of yearlong series on urban agriculture in greater Paris, attracted a standing-room-only crowd. Around the theme “Urban Agriculture: From Farm to Plate,” the various participants agreed that metropolitan Paris would probably never be self-sufficient in food. But they also agreed that the social and environmental benefits of urban agriculture could no longer be ignored, and that the current model of urban expansion is unsustainable. The series, designed to reveal “what is already happening in urban agriculture,” in the words of Vianney Delourme of Enlarge Your Paris, kicked off last September with a photogenic amble through the streets of northern Paris with Clinamen’s sheep; it will culminate in July with a sheep walk around the entire periphery of the city.

In a landscape that appears anything but pastoral, the sheep entrance passers-by. When I walked with them on their migration to winter quarters in a sheepfold in the Parc Georges-Valbon a few weeks ago, a group of young men stopped to take selfies with the sheep, and a shopkeeper called out an offer to buy one for 600 euros. (Dubreuilh told him the sheep weren’t for sale.) An elderly Algerian woman in traditional headscarf and robe broke into a smile as we passed her house, and when I asked another woman on the sidewalk what she thought of the sheep, she laughed and replied: “Oh, you know, I’m a country girl. I grew up with farm animals.”

After the sheep were safely corralled in their shelter, Dubreuilh invited me to join her and her fellow shepherds for lunch in their headquarters. As we prepared and ate a meal of scrambled eggs and sautéed vegetables, she told me she and her shepherding partner at Clinamen, Guillaume Leterrier, “became urban shepherds because we think that when people interact with animals, they become more human.”

“When people come across a flock of sheep, they slow down, they adopt the pace of the animals,” she said. “They reflect on their own rhythm, on their daily routine. A flock of sheep brings humanity and freedom to the city.”