For Mik

Our son’s love of trains was once so absolute I never foresaw it could be replaced. New York City is a marvelous place to live for train-obsessed boys. When he was three and four, we spent many a rainy day with no particular destination, riding the rails for the aimless pleasure of it, studying the branching multicolored lines of the subway map, which he’d memorized like a second alphabet. I’d hoist him up to watch the dimly lit tunnel unfurl through the grimy front window of the A train’s first car as it plunged us jerkily along the seemingly endless and intersecting tracks. Some rainy mornings, our destination was 81st Street, where we exited the B or C with dripping umbrellas and his little sister in tow to enter the American Museum of Natural History.

There, at a special exhibition called “Nature’s Fury,” our son’s attention turned like a whiplash from trains to violent weather. Even before this show, the museum demanded a certain reckoning with the violence of the Anthropocene. What grownup wouldn’t feel a sense of profound regret confronting the diorama of the northern white rhinoceros in the Hall of African Mammals, or the Hall of Ocean Life’s psychedelic display of the Andros Coral Reef as it looked in the Bahamas a century ago? Meandering the marble halls of the Natural History Museum is like reading an essay on losing the Earth through human folly. Yet none of its taxonomies of threatened biodiversity, not even the big blue whale, moved my kindergartner like “Nature’s Fury.”

The focus of the immersive exhibition was on the science of the worst natural disasters of the last fifty years—their awesome destructive power and their increasing frequency and force. Accompanied by a dramatic score of diminished chords and fast chromatic descents, the exhibit meant to show how people adapt and cope in the aftermath of these events, and how scientists are helping to plan responses and reduce hazards in preparation for disasters to come.

“Are they too young for this?” my husband questioned, too late. Our impulsive boy had darted ahead and cut the line to erupt a virtual volcano. I supposed it made him feel less doomed than like a small god that, in addition to making lava spout at the push of a button, the kid could manipulate the fault lines of a model earthquake, set off a tsunami, and stand in the eye of a raging tornado.

In the section on hurricanes at a table map of New York, the boy was also able to survey the sucker punch that Hurricane Sandy delivered to the five boroughs. This interactive cartography was a darker version of the subway map he’d memorized, detailing the floodplains along our city’s 520 miles of coast. I can still see my boy there, his chin just clearing the table’s touchscreen so that his face was eerily underlit by the glow of information while my girl crawled beneath. Seventeen percent of the city’s land mass flooded, leaving two million people without power, seventeen thousand homes damaged, and forty-three people dead. On the map, the water was rising to overtake the shorelines at Red Hook, Battery Park, Coney Island… All across the Big Apple, the lights were going out.

“Come away from there,” one or the other of us called uneasily, because we weren’t prepared to confront what climate change would mean for our children, to say nothing of our children’s children. The boy was five at the time. The girl was three. In their lifetimes, according to a conservative estimate in a recent report by the NYC Panel on Climate Change, they could see the water surrounding Manhattan rise six feet. We pulled them away from that terrifying map of our habitat to go look at dinosaur bones—an easier mass extinction to consider because it lay in the distant past.

What strikes me now as irrational about our response isn’t our ordinary parental instinct to protect our kids from scary stuff. It was our denial. Their father and I treated that display as a vision we could put off until later when it clearly conveyed what had already transpired. “We are now faced with the fact, my friends, that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now,” preached Martin Luther King Jr. in 1967 in one of his lesser-known sermons, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” He may as well have been speaking on climate change. Sandy made landfall in 2012, the year after the boy was born, while I was pregnant with the girl. It gave a preview of what the city faces in the next century and beyond, as sea levels continue to rise with melting ice sheets. The storm exposed our weaknesses, and not just to flooding. I remember that when the bodegas in our hood ran out of food, some folks shared with their neighbors. But when the gas station started running out of fuel, some folks pulled out their guns.

Advertisement

As much as we may worry about our kids’ future, it’s already here.

Avoiding the map didn’t annul its impact on our son. The subject of storms had gripped his consciousness as surely as his author-father’s had been gripped by horror films. That part of the boy’s brain that previously needed to know the relative speed of a Big Boy steam engine to a Shinkansen bullet train now needed to know what wind speed differentiated a category-four hurricane from a category-five. Soon enough, and for months afterward, Mr. Wayne, the friendly librarian at the Fort Washington branch of the New York Public Library, would greet our boy with an apology. There were no more books in the children’s section on the subject of violent weather than those he’d already consumed.

At bedtime, while his sister sucked her thumb to sleep, I offered my son reassurance that we weren’t in a flood zone; that up in Washington Heights—as the name suggests—we live on higher ground. “You’re safe,” I told him.

“But the A was flooded during Sandy,” he reminded me, matter-of-factly. “The trains stopped running and the mayor cancelled Halloween.” Then he’d go on rapturously about the disastrous confluence of the high tide and the full moon that created the surge, while I tried to sing him a lullaby.

Eventually, a different fixation overtook extreme weather, and another after that. Such is the pattern of categorical learners. It may have been sharks before the Titanic, or the other way around—I’ve forgotten. Two years have passed since we saw “Nature’s Fury”; a year and a half since our president led the US to withdraw from the Paris climate accords. The boy is seven now, what Jesuits call “the age of reason.” The girl is five and learning to read. If current trends continue, the world is projected to be 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than pre-industrial levels by the time they reach their late twenties. The scientific community has long held two degrees Celsius to be an irreversible tipping-point. Two degrees of global warming, according to the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), marks climate catastrophe.

At two degrees, which is our best-case climate scenario if we make seismic global efforts to end carbon emissions, which we are not on course to do, melting ice sheets will still pass a point of no return, flooding NYC and dozens of other major world cities; annual heat waves and wildfires will scrub the planet; drought, flood, and fluctuations in temperature will shrink our food supply; water scarcity will hurt four hundred million more people than it already does. Statistical analysis indicates only a 5 percent chance of limiting warming to less than two degrees. Two degrees has been described as “genocide.”

In fact, we’re on track for over four degrees of warming and an unfathomable scale of suffering by century’s end. By that time, if they’re lucky, our children will be old. It’s pointless to question whether or not it was ethical to have them in the first place since, in any case, they are here. Their father writes about imaginary horrors. For my part, I’m only beginning to see that the question of how to prepare our kids for the real horrors to come is collateral to the problem of how to deal as adults with the damage we’ve stewarded them into.

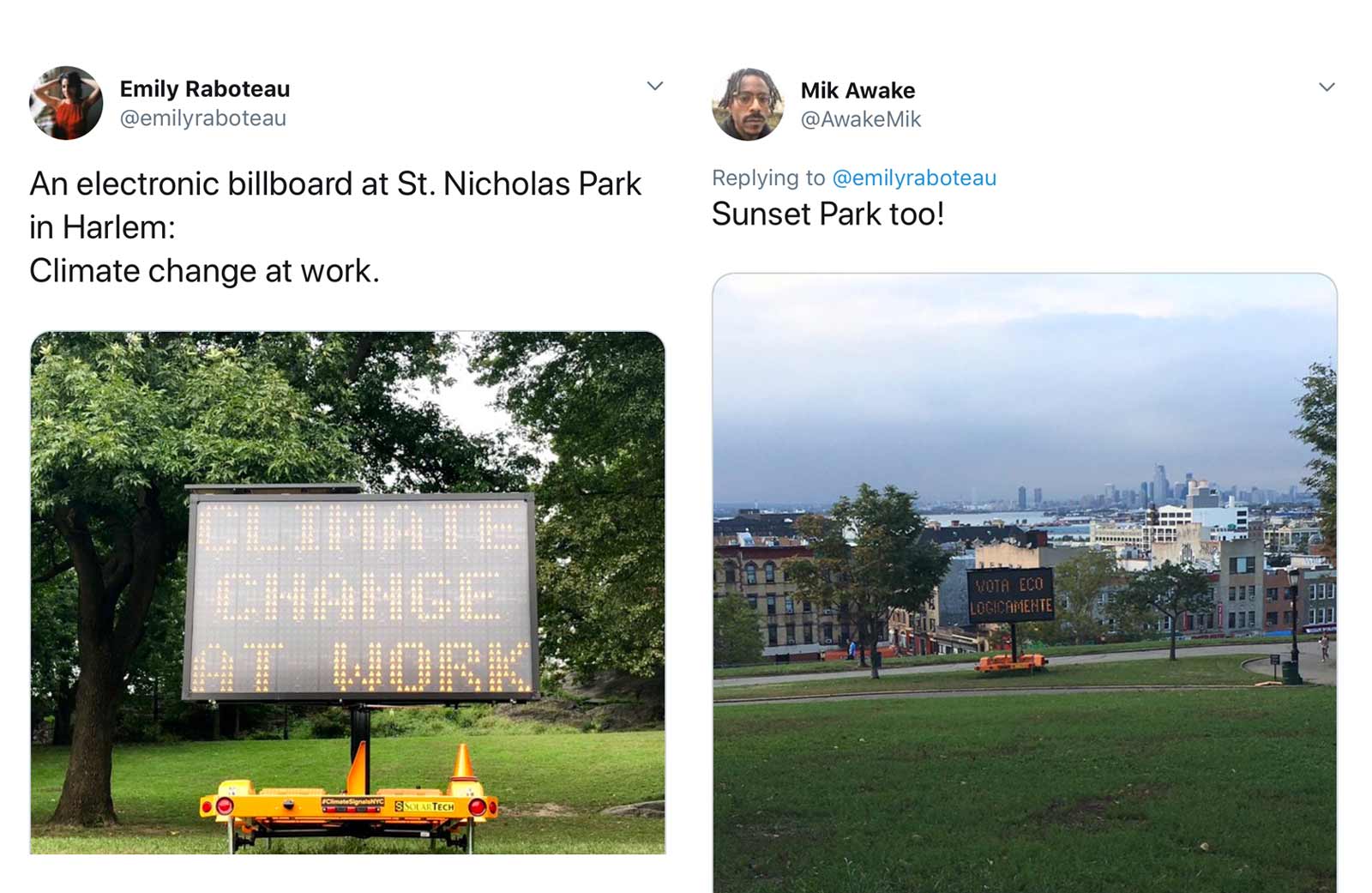

What helped me to see this was a road sign. I came across it this fall in Harlem’s St. Nicholas Park two weeks before the release of the UN’s Climate Report that concluded we must reduce greenhouse gases to limit global warming to the 1.5-degree threshold. The sign was part of another exhibit, but I didn’t know that when it stopped me in my tracks on my way to work. It was one of those LED billboards you normally spot on a highway, alerting drivers to icy conditions, lane closures, or other safety threats ahead. Oddly enough, the sign was parked in the grass two thirds up the vertiginously steep slope to City College. How did that get there, I wondered. More surprising than the traffic sign’s misplacement was its message:

“CLIMATE DENIAL KILLS.”

St. Nicholas Park recently ranked among NYC’s top five most violent parks, as measured by high rates of crime. I was assaulted there once by a girl in a gang who coldcocked me in the face. This sign hit me almost as hard. I felt like someone had punched through from another dimension to shock me awake. Was I seeing the sign correctly? Yes. It repeated its declaration in Spanish:

Advertisement

“LA NEGACIÓN CLIMÁTICA MATA.”

Every couple seconds the sign refreshed, unspooling a disquieting, if strangely droll, string of warnings:

“NO ICEBERGS AHEAD”

“50,000,000 CLIMATE REFUGEES”

“CAUTION”

“CLIMATE CHANGE AT WORK”

“ABOLISH COAL-ONIALISM,”

and so on.

The familiar equipment of the highway sign gave authority to the text. Because it was parked in the wrong place, the sign appeared hijacked—as in a prank. I understood myself to be the willing target of a public artwork but not who was behind it. The voice was creepily disembodied. I admired its combination of didacticism and whimsy. But even with its puns, the sign was more chilling than funny. The butt of the prank was our complacence, our lousy failure to think one generation ahead, let alone seven, as is the edict of the Iroquois’ Great Law.

For several minutes, I paid humble attention to the sign, unsure how to react. The only practical guidance it offered was “VOTE ECO-LOGICALLY”—something achievable given the upcoming midterm elections. But what else was the sign telling us to do? My individual practice of composting and giving up plastic bags felt lame when the headlines were warning of genocide and civilization’s end. I began to feel exposed, standing there, and briefly considered that I might be on Candid Camera.

I looked around the park for help, half-hoping the artist might pop out from behind a tree to explain him- or herself. I wanted to process the work’s messaging with somebody else. It signaled the tip of a melting iceberg whose magnitude surpassed my cognition. How to move past the paralyzing fear that whatever we do is too little, too late? The trouble here was one of scale. Sadly enough, no one else in the park that morning seemed engaged by the sign at all. And so I snapped a picture of it with my iPhone and shared it on Twitter.

Almost immediately, a stranger with the handle @AwakeMik replied with a photo of an identical sign he’d just discovered in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, while walking his dog, Chester, named after Himes. “VOTA ECO-LOGICALMENTE,” it said. His wide-angle photo was better than my close-up shot because he’d framed the sign at dusk in the broader context of the cityscape.

I felt a sudden kinship with this man, Mik Awake, who’d noticed the same thing I had, from a broader perspective. The two signs were clearly of a piece. Intrigued, I did some Internet sleuthing and discovered that they were part of a larger series by environmental artist Justin Guariglia, in partnership with the three-year-old Climate Museum and the Mayor’s Office. All in all, there were ten climate signs staged in public parks across the city’s five boroughs—many of these in low-lying neighborhoods near the water, most vulnerable to flooding.

The Climate Museum’s website described Guariglia’s project as an effort to confront New Yorkers with how global warming affects our city now; to “break the climate silence and encourage thought, dialogue and action to address the greatest challenge of our time.” To that end, the signs’ messages were programmed with translations in languages spoken in the various neighborhoods in which they appeared: Spanish, French, Russian, and Chinese. Thus embedded in the diverse cultural landscape of New York City, the billboards projected a forecast of what we stand to lose with the rising sea. The Climate Museum’s website also offered a city map indicating the locations of the ten signs, with clear directions via public transportation to each. Finally, it introduced an adventure: anyone who could prove they’d visited all ten signs would receive a prize.

I studied the map with a mix of obligation and gratitude. It reminded me of my earlier failure to process reality at the American Museum of Natural History. Here was an opportunity, perhaps, to do better—if not with my kids yet, then at least with another concerned citizen. I decided to take the artist’s invitation to heart. On a lark, I asked Mik Awake if he’d be willing to navigate Guariglia’s climate signs with me. Amazingly, given the time commitment, the soberness of the topic, the complicated semiotics, and the distance the pilgrimage would carry us, he said yes.

We had until midterm election day when the signs were scheduled to come down. By visiting one or two a week, between September and November of this unseasonably warm fall, we managed to witness them all. I’ve come to think of this period of my life—part scavenger hunt, part Stations of the Cross—as “Thursdays with Mik.” By now we are no longer strangers, but friends. What follows is an account of our journey to grasp the effects of global warming on the place where we live.

The first sign Mik and I saw together sat at the end of Pier 84 in Hudson River Park, halfway between his neighborhood and mine in what was commonly known as Hell’s Kitchen. Thanks to real estate development, it’s now often referred to by the tonier names of “Clinton” and “Midtown West.” To get there, I took the downtown A to 42nd Street and pushed west through the crush of tourists gazing up at the digital billboards of Times Square, wondering if those poor suckers knew they were looking at the wrong signs.

Only someone not from New York City would describe Times Square as the heart of the metropolis. Most of us who are native to the city steer clear of it, especially on New Year’s Eve. But today, it couldn’t be avoided. Passing through the clogged commercial district on my mission, I recalled an unnerving image from the short film, two°C by French filmmaking duo Menilmonde. New York City is depicted in this movie as an Atlantis in the making, subsumed by the rising waters, with the Hudson and East Rivers converging to swallow a Times Square devoid of anyone to watch the blinking ads.

Is it possible to be haunted by the future as well as the past? The precise and intimate term for this feeling is “solastalgia,” the desolation caused by an assault on the beloved place one resides; a feeling of dislocation one gets at home. I suppose one might feel this in the case of war, domestic abuse, or dementia, but the difference with environmental upheaval is the ingredient of guilt. I walked past the bright theater marquees and the slovenly Port Authority bus station, the brownstone on 43rd Street where my friend C. had thrown me a baby shower in her rent-controlled garden apartment, past the high rise on 10th Avenue where I’d screwed my high-school boyfriend on his parents’ ratty foldout couch—past my former selves, and the ghosts of twentieth-century peepshows and nineteenth-century slaughterhouses, to join my partner at the waterfront.

Here is Mikael Awake, a few weeks shy of his thirty-seventh birthday. He’s the kind of guy who’s at ease quoting Paul Éluard (“La terre est bleue comme une orange…”) and whose friends ask him to officiate their weddings—a contemplative, caring, stylish man; the hardworking son of Ethiopian immigrants. Mik’s last name is pronounced “ɑ-wə-kə,” but its meaning in English fits his character. That is, the brother is politically “woke,” stumping hard this election cycle for Stacey Abrams to become the nation’s first black female governor down in Georgia, his home state. Mik grew up as one of few kids of color in the schools of Marietta. When I asked him what that was nearby, he joked, “Racism,” before conceding, “Atlanta.”

According to the logic of social media that has shrunk the planet, we’re separated by only one degree, sharing several acquaintances and interests in common. Both of us are writers, and teach writing at CUNY—a vocation, we agree, that brings us closer to the city by putting us in touch with its strivers. We may eventually have crossed paths another way. He’d been following me on Twitter. But it was the climate signs that brought us together.

My instinct is to focus my lens on Mik, but, unwittingly, he’s already taught me to take a step back. Still, the viewfinder can’t capture it all. What I mean to show is too big. I settle for framing the tension between the human, the landscape, and the sign. This method will become our pattern.

To the right of the frame floats the former aircraft carrier USS Intrepid; to the left lies the Circle Line cruise ship departure site. The Hudson rolls by behind Mik. Beneath the river, the busy Lincoln Tunnel connects to New Jersey on the other side. Flooding of the tunnels into and out of Manhattan (along with flooding of the subway and energy infrastructure) have been identified as serious vulnerabilities in the Climate Change and a Global City: Metropolitan East Coast Report, a pre-Sandy document that examined climate-change impacts in New York.

Cyclists zip along the two-lane greenway in front of Mik. The bike path is but one perk of Hudson River Park, which was refurbished from the crumbling docks of a once grubby industrial waterfront as part of the city’s renewal wherein, over the last generation, warehouse districts have steadily transformed into luxury housing. Sandy wreaked $19 billion in damage to the city, yet the rate of development along our coastlines has only increased since that superstorm. We have more residents living in high-risk flood zones than any other city in the country, including Miami. Local city-planning experts are rightly concerned about how we’ll cope when the next great storm surge inevitably strikes.

After Sandy, Mayor Bloomberg declared that New Yorkers wouldn’t abandon our waterfront. He, and de Blasio after him, have worked to revise codes to make new buildings more climate-resilient with flood-proofing measures such as placing mechanical equipment on higher floors, but each mayor has seen real-estate interests in waterfront development as too precious a political constituency to suppress. In my picture, Mik faces 12th Avenue, across which, and slightly southeast, construction on the glassy towers of the huge Hudson Yards project is topping out, surrounded by a phalanx of cranes. Hudson Yards is one of many recent projects sited within the NYC climate change panel’s projected floodplain for 2050, when sea-level rise could reach 2.5 feet—meaning that all the tall buildings Mik and I behold cropping up at the waterline are shortsighted in that, gradually, they’ll find their foundations inundated.

Investors tend to think in the short term, in the length of mortgages, according to the timelines of insurance policies. Even the newspaper headlines are guilty of this fallacy, tending to present Armageddon in the near future. Whether we frame it as twelve years away, or thirty, or fifty, or refer to ourselves as the last generation that can stop climate change, we seem to keep pushing back the clock, as if the countdown to the ball drop has only just begun. But when did the clock start ticking?

Over Mik’s shoulder the sign flashes its warning. How well the city’s personality coheres in the bustling elements that surround my new friend: defense, tourism, transport, development, expansion, confrontation, bullheadedness, and art. Yet my picture, like that short disaster film, is eerily pastoral, as if Mik were the sole survivor of nascent catastrophe.

His face registers concern. I won’t venture a mutual diagnosis of eco-anxiety, the emerging condition described by the American Psychological Association as the dread that attends “watching the slow and seemingly irrevocable impacts of climate change unfold, and worrying about the future for oneself, children, and later generations.” I’m no clinician and such a prognosis pales in comparison to the plight of a person in Puerto Rico still without power post-Maria, or a farmer in India driven to suicide by his perennially scorched crops. We’re privileged not to have been directly hit yet, as have so many in the Global South. It’s our temporary luxury to consider global warming intellectually rather than materially. We have, as black Americans, each in our own way, more immediate threats to battle. Nevertheless, Mik confides in me that his stress makes him compulsively pick at his face. I confess to habitually clenching my shoulders, and the nerve pain resulting from the Atlas-like tilt in my neck. The stimuli are not exaggerated. The glaciers are melting. The water is rising. These are our body’s signs.

The second and third signs we toured were located on Governor’s Island. Situated in New York Harbor between Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn, the island was used from 1755 to 1996 as a military post by the US Army and Coast Guard. Dredged debris from the harbor and landfill from subway excavation were used in the early 1900s to more than double the island’s size—an illustration of the innovative if hubristic remaking of topography that’s characterized the city for centuries. In 2003, the city bought Governor’s Island from the federal government for a dollar. Since its transfer to the people of New York, the island has been used as a public park, accessible by ferry to day-tripping civilians like us.

There’s a public school on this island. An organic farm. Artists’ studios. Playgrounds. A fifty-seven-foot slide. A “glamping” (glamorous camping) retreat. There were even at one point a pair of friendly goats named Rice and Beans, and a miniature golf course. Its elevated hills were designed with climate change in mind. The cinematic view it offers of Lower Manhattan is glorious—the stuff of a Gershwin score. I had never been to Governor’s Island before, though it’s a place my children would fancy. The October day Mik and I made our visit was warm enough for shorts.

To the left of my picture’s frame stands the circular sandstone fort, Castle Williams, built in 1811 to defend the rich Port of New York against a naval assault that never came. Mik looks past the climate sign toward the dense cluster of buildings of the Financial District; at the ghost limbs of the Twin Towers and the arrogant blue spike of the Freedom Tower sticking up like a middle finger. That precious spit of land beneath Mik’s gaze seats a $500 billion business sector that influences the world’s economy. Of course, the Financial District wasn’t the only part of Lower Manhattan devastated by Sandy. Within a ten-mile perimeter, 95,000 low-income, disabled, and elderly residents suffered because all of downtown—like Governor’s Island itself—lies in a flood plain. In downtown Manhattan, as in other low-lying neighborhoods at the water’s edge, communication and transportation were cut off, infrastructure was damaged or wrecked, and thousands were without running water and power. Mik and I contemplate the irony of the prior use of Governor’s Island for defense when the real threat of attack to the city is the water surrounding it.

Also under Mik’s gaze is a tidal gauge off the southern tip of Manhattan. Measurements taken there indicate roughly a foot of sea-level rise in the last century. Climatologist Cynthia Rosenweig, who served on the IPCC, has compared sea-level rise to a staircase. “The twelve-inch increase in NY Harbor over the last century means we’ve already gone up one step. When a coastal storm occurs, the surge caused by the storm’s winds already has a step up. Continuing to climb the staircase of sea level rise means we’ll see [a] greater extent and frequency of coastal flooding from storms, even if the storms don’t get any stronger, which they are projected to do,” she said in a post-Sandy interview for Climate.gov.

So what are city planners doing to protect Lower Manhattan? In Sandy’s wake in 2013, the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Rebuild By Design competition invited proposals for climate-resilient flooding solutions to protect against future storms. One of the seven finalists’ designs, Bjarke Ingel’s BIG U, a vast ten-mile barrier system with a series of levees is now underway, with the first phase of construction planned to begin in the spring.

Naysayers argue that such barriers won’t save Howard Beach and other parts of southern Queens and Brooklyn; that a sea wall enclosing the narrows of New York Harbor still leaves Long Island in trouble, that these halting projects to save the city will take too long, or fall short of the watermark, shifting the burden to stay afloat onto our children. Meanwhile, students at the high school on Governor’s Island are gamely helping to restore the ecosystem of the Harbor with oysters which, before they were killed off with the dumping of toxic waste and raw sewage into their reefs, once served as the base that made this estuary one of the most dynamic, biologically productive, and diverse habitats on the planet. It occurs to me that this hopeful act contradicts the apparently anthropocentric sign, “HUMAN AGENDA AHEAD,” insofar as other forms of life are being taken into account.

“What do you think this sign means?” Mik asked me. It was the most enigmatic of Guariglia’s messages. The signal seemed to suggest both itself and its opposite—accusing the emblem of capitalism in the background of a greedy agenda that’s laid waste to the planet, while perhaps, at the same time, appealing to its beholder to be more humane, putting people before profit.

Later, I called the artist at his Brooklyn studio to ask about the climate signals, and to clarify this one in particular. “That one came out of the notion that we live in a corporatocracy,” Justin Guariglia explained, quoting the bon mots that it’s simpler to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. “Corporations want this news hidden. Big business has had next to no incentives to care for the earth, though you’d think the preservation of the human race would be incentive enough.” The project was meant to compel people to think ecologically, he told me, and was influenced by the object-oriented ontological writing of eco-philosopher Timothy Morton, as well as the text-based work of neo-conceptual artist Jenny Holzer:

We need to get more human-focused but not more anthropocentric. As a human, I’m on the same ontological playing field as garbage and galaxies—not above. As a visual artist, I’m trying to engage with a huge thing operating on several levels requiring several languages. This is an exceptionally urgent problem. It needs to get out into the broad public and raise consciousness. That’s the responsibility of artists and writers. Not the corporations.

I know from a photograph that Guariglia’s left arm is tattooed with a wavy line representing 400,000 years of carbon dioxide levels in the earth’s atmosphere. It spikes at his pulse point and encircles his wrist like a handcuff. He embodies this stuff. Why the road signs, I asked.

“The medium of the highway sign is embedded with so much information,” he said. “It’s hyper-accessible, and a symbol of authority. People see roadwork signs and think, ‘government.’ They have a limbic response. I wanted to communicate on a broad public level and have people subconsciously absorb it.”

I confessed to having difficulty absorbing the message, and to feeling very small in the shadow of the signs. The artist understood.

Because Guariglia recently traveled over Greenland with NASA to photograph quickly melting polar icecaps, he spoke on a more personal level about a particular pockmarked “galloping glacier” (so-called for the rapidity of its flow): “Could my brain really make sense of an object warehousing 38 million Olympic sized swimming pools of water? Or the scale of a 100,000-year-old hunk of ice the size of California on the verge of calving from an ice sheet? No, but we have to talk about what happens when all this ice melts. Where’s it going?”

Mik asked me at Yankee Pier on the other side of Governor’s Island what I thought of the signs as art. I considered whether or not I liked them. It was as if, after a doctor diagnosed one of my kids with cancer, someone else in the waiting room of the ER asked my opinion of that doctor’s beard. The signs didn’t offer any solace. I hated what they suggested. I did like that they’d brought us to a place offering fresh angles on the city. Mainly, I liked the signs for connecting me with Mik. In my picture, the choppy Buttermilk Channel flows behind him, and off in the distance the elegant arc of the Verazzano Narrows Bridge connects Brooklyn to Staten Island.

When I asked him, in turn, whether he liked the signs, Mik answered that they made him feel less alone.

Before leaving the island, we stopped at the Climate Museum’s temporary hub in the Commander’s house within a cluster of stately buildings that once served as officers’ quarters. There, visitors were invited to simulate their own climate signs. These read like postcards from the brink, bumperstickers, or protest slogans:

“SEE YOU ABOVE SEA LEVEL!”

“ISLAND NATION JUSTICE.”

“MAKE AMERICA GREEN AGAIN.”

A pamphlet informed us that the Earth’s glaciers hold enough water to raise sea levels by roughly 230 feet. Mik wrote:

“WATER IS THE IMMIGRANT THEY SHOULD FEAR.”

The Climate Museum is the nation’s first museum dedicated to climate change. I later asked its director, Miranda Massie, to comment more elaborately about the organization’s mission. Massie responded in an email about how art, even art with a dark message, can inspire us, “consciously or not,” by reminding us of human creativity and potential:

Museums have strengths including popularity and trust that make them essential to the cultural shift we need to see on climate. Art in particular has the power to move the needle on climate engagement and action for a couple of reasons. It reaches us physically, emotionally, and communally, where we really live. Climate change can seem abstract even in the middle of a hurricane. To fully confront the immense challenge posed by the crisis, we need a visceral sense of reality. We also need to be able to experience the full range of emotions art evokes—awe, grief, surprise, fury, tenderness… And perhaps most of all, we won’t make progress without each other—and art builds community. It is a soft pathway into climate dialogue that lifts climate out of perceived polarization and stigma, allowing us to break the climate silence.

To talk about this subject seriously is to risk being called a doomsayer or a scold. Massie told me that 65 percent of people in the US are worried about climate change, but only 5 percent of us speak about it with any regularity. (Since our correspondence, the number of Americans fearful of climate change has been identified by a Yale poll as surging to more than seven in ten.) In truth, Mik and I talked less in the beginning about climate change than about our lives—his book in progress, our respective lesson plans, the imminent midterm elections, the costumes my children were planning for Halloween… But now I know we were also stumbling together on a path toward new language, led by the signs.

The following week, we ventured out to Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens to see the fourth sign. The park was empty that Thursday on account of a torrential downpour. We were feeling the sultry edges of Michael, a category-four hurricane that made landfall in Florida the day before. The radial pathways leading to the Unisphere were washed out. In the nearby isthmus neighborhood of Willets Point, where permanently flooded streets are bordered between Flushing Bay and the Flushing River, hundreds of small businesses are being torn down and relocated to make room for a multibillion-dollar mega-project. By the time we reached the sculpture, notwithstanding our umbrellas, Mik and I were both soaking wet. Visibility was so poor through the sheets of rain that we couldn’t immediately spot the sign, and so we orbited the Earth, like two lost satellites, until we found it by Africa, stuck on the word, “CAUTION.”

On the new Google Earth plugin, Surging Seas: Extreme Scenario 2100, created by Climate Central, which uses data from a report by the National and Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to make projections based on the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, the future map of Queens shows that, unless the US transitions to clean energy alternatives, Flushing Meadows Corona Park will be engulfed. So will JFK and LaGuardia airports, sections of north Astoria, College Point, and most of the Rockaways, while large swaths of Long Island City will be submerged in water. You can zoom in tight on the map. From an unscientific perspective, the flooding can appear Biblical, like the wrath of a punishing God. For example, the site of the pizza joint in Howard Beach—where, in 1986, a mob of white thugs wielding baseball bats reportedly taunted twenty-three-year-old Michael Griffith and his friends, “What are you doing in this neighborhood, niggers?” and then attacked and chased them toward the Belt Parkway where Griffith was killed by an oncoming car—will be mercilessly drowned.

Mik stands on a step, to avoid a puddle. The 350 tons of the steel Unisphere, which was the central icon of the 1964–1965 World’s Fair, is more imposing in person than I had anticipated. Yet, in the context of the sign, and softened by a veil of mist, the Earth it represents appears fragile, nearly delicate. The gauzy material of Mik’s shirt echoes the fountain spray. Under his umbrella, and next to the lamppost dividing my picture, Mik looks like a version of Gene Kelly, too pensive to dance. The lamp at the top of the post marks South Sudan, just west of Ethiopia, whence Mik’s parents fled Mengistu’s Red Terror.

We discussed the comparative effects of climate change in the Horn of Africa and here on the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. While that part of the world is drying out, leading to shriveled crop yields and water shortages that in turn contribute to conflict, famine, and forced migration, this part of the world is getting more precipitation. Between 1958 and 2012, the Northeast saw a more than 70 percent increase in the amount of rainfall measured during heavy precipitation events, a greater increase than in any other region in the nation, according to the EPA. That we’re getting warmer and wetter here, however, doesn’t mean we won’t also feel drought conditions in summer. We will.

All-time heat records were set all over the world last summer, including in our global city. Some days were so hot I questioned whether it was safe to send my kids to day camp. By 2050, New York’s average temperature is projected to rise between 4.1 and 6.6 degrees Fahrenheit, while annual precipitation is expected to increase between 4 percent and 13 percent. The regional trend toward more rain has exacerbated localized flooding—not only during big storms, but also as a matter of course at high tide, since the ocean is already brimming. Street floods are a regular nuisance in some low-lying areas of Queens like Hamilton Beach. Residents there have grown accustomed to swans and fish swimming in knee-high water in the middle of the road when the moon is full.

Perhaps the most common place the average New Yorker experiences flooding is the subway. Even on dry days, the MTA is tasked with flushing from its network some 13 million gallons of groundwater with overworked pumps. When flash floods from heavy rain swamp the tunnels, those of us who commute are routinely delayed, spending more and more time griping underground.

Out in Queens, the 7 line is elevated. Mik and I didn’t stay long, not just because of the inclement weather but also because he was scheduled that afternoon to sign on a townhouse he and his wife were purchasing in Flatbush, Brooklyn. They made sure the property lay outside the floodplain before making their offer. Sloshing our way back to the train near the Mets Citi Field ballpark, he showed me the inscribed Mont Blanc pen he planned to sign the contract with—a graduation gift from his brother. He looked the part of a proud first-time homebuyer on the verge of the American Dream.

Until they make the move to their new home, Mik, his wife, and their dog Chester will still live in the low-lying waterfront neighborhood of Sunset Park, where nearly a third of the residents live below the poverty line. I joined him there in the park of the same name to visit the fifth sign. Like other disadvantaged communities, this one bears the burden of environmental pollution and impacts of climate change. In addition to being susceptible to flooding, Sunset Park endures poor air quality because of passing traffic on the Gowanus Expressway and three nearby fossil fuel plants whose pollution, ironically, adds a pretty afterglow to the neighborhood’s already remarkable sunsets.

Mik and I met hours before sunset, at high noon. In my picture, he stands squarely on his shadow, almost camouflaged with the trunk of the tree that appears to branch from his head. The dark blue water of the Upper Bay is just visible at the horizon line. What you can’t see is the gang of tough old Chinese women doing Tai Chi behind me by the tennis courts, in the sudden cold. They belong to a large Chinese population in Sunset Park, which boasts New York City’s largest Chinatown. Appropriately, the sign addresses that part of the neighborhood’s demographic in Chinese. Autocorrect as Freudian slip: when I later asked Kimm, the Chinese midwife who delivered my children, to translate the sign, she texted, “It’s weird—‘Human Agenda for the Futility.” And then, “Oops!—‘Future’.”

Donald Trump has accused climate change of being a fabrication on the part of “the Chinese in order to make US manufacturing non-competitive.” He also appointed fossil-fuel advocates to lead the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Energy. What makes this denial and disregard so egregious is that the US is the second largest contributor of CO2 to our planet’s atmosphere, though we’re home to only 4.4 percent of its population. It would take four Earths to provide enough resources for all if everyone in the world consumed as much as we do in the US.

Interestingly, Sunset Park is home to the city’s first grassroots-led, bottom-up climate adaptation and resiliency planning project. Following Sandy, community members organized into a block-by-block, building-by-building plan for action called the Sunset Park Climate Justice Center. The organization’s mission includes supporting local leaders “to coordinate allocation of community resources and mitigate the impacts of future severe weather, including the possible release of harmful chemicals.”

Since many workers in Sunset Park are employed by natural gas and power plants that could be shut down or curtailed as new climate regulations take effect, activists have appealed to the governor to let communities like Sunset Park lead the development of a transition plan for workers in the fossil-fuel industry to find good-paying new jobs in the regenerative energy economy—in other words, to play an active role in their own adaptation. One example of climate adaptation underway in Sunset Park is a new initiative to shift to renewable energy on a cooperative ownership model. An 80,000-square-foot solar garden is under development nearby on the roof of the decommissioned Brooklyn Army Terminal. It will start to operate this year, open especially to low-income residents. Aiming to serve some 200 families as well as businesses, the solar array will be one of the country’s first models of a cooperatively owned urban power supply, cutting energy costs and emissions for subscribers.

It’s inspiring to uncover local action taking place despite federal inaction. It’s a drop in an ocean-sized bucket of hypoxic tepid water, but it’s inspiring. Mik told me that he and his wife were looking into applying for a solar rebate initiative and exploring how to green the roof of their new house. I thought it would be impertinent to ask if they planned on having kids, though I believe he’d make a great dad. We discussed their plans for renovation while Chester chased his tail in widening circles.

The sixth sign stood way out in Far Rockaway, Queens. I could have traveled there on the A train, but I chose to go by water. As usual, I was running late. I rushed through Battery Park’s tight warren of streets over the African Burial Ground in time to catch the ferry at Wall St./Pier 11. The Freedom Tower jutted above, like the blade of a sundial. I ran past jackhammering workmen in orange vests and hardhats, the stock exchange, a discount store that used to be an outpost of The Strand, and on tiny Maiden Lane, the ghost of myself aged twenty-five, disoriented and breathing dust, having walked over the Brooklyn Bridge on Rosh Hashanah to stumble upon Ground Zero a week after the World Trade Center attack. I jumped at the blare of a horn: a Moishe’s moving truck rolled through a red light, nearly mowing me down. I was struck by how quickly the city remakes itself. These narrow, cobbled streets were made for horses. I raced waterward down Stone Street, aware of the ticking clock. Flanking the terminal were the Brooklyn Bridge and a noisy helipad. Barges. Water taxis. Seagulls. At Slip A, one dockworker playfully grabbed another from behind: “Yo, you got documentation? This is ICE, assume the position.” A ticket to Rockaway Beach cost $2.75, the same as a subway fare.

The ferry windows were grubby. Seeing out of them was like watching a dream sequence. The shapes at the edges of Brooklyn were hard to discern: construction cranes, IKEA, a windmill, rooftop water tanks like the hats of witches, shipping containers, men with fishing poles. Mik embarked at Sunset Park, somewhat shaken—the day before, a bomb had been delivered to the CNN building, close to his wife’s workplace.

On the boat ride, Mik and I discussed living in a post-September 11 state of alert, often fearing for our loved ones’ safety. Recently, my children were evacuated from their school, where they regularly practice soft lockdown drills for active shooter incidents. This is something beyond the quotidian mental exhaustion that comes from urban living. Behavioral studies have found city-dwellers pay more attention to dangers and opportunities but less attention in general. In spite of our sensory overload, or because of it, the climate signs have demanded our attention.

As we were ferried over the water lapping at Brooklyn’s coast, through Gravesend Bay, past the Wonder Wheel at Coney Island and Brighton Beach toward Broad Channel, Mik and I imagined the heightened state of alert that must attend living on the coast. And yet, we envied our neighbors on the coastline their view. When you live, as my family does, in a mid-rise apartment building with a foreshortened view of the building across an alleyway of battered trashcans, it’s easy to forget you’re near water. New York’s master-builder Robert Moses made it harder for pedestrians to access the rivers, creeks, straits, lagoons, and bays surrounding New York City, by hemming in the city with so many expressways. It takes a mental leap to make the worthwhile plunge.

Neither Mik nor I had ventured to Rockaway Beach before; we’d become tourists at the outer reaches of our own city. The ferry took its time. The sky opened out. We felt the primal allure of water, the drag of the vessel upon it. Soon enough, our heart rates slowed. Melville writes, at the opening of Moby-Dick, about gravitating toward the sea: “It is a way I have of driving off the spleen.”

A feeling of danger gave way to a feeling of opportunity. We disembarked at Rockaway Peninsula, an eleven-mile strip of two family homes and public housing projects. A dome of gold light hovered over it, cast by the double reflection of Jamaica Bay and the Atlantic Ocean on the other side. On the free shuttle bus that drove us closer to our destination, I wondered aloud if people who live and work on the water feel happier. A local man with a Russian accent answered yes. “Why do you think people come all the way out here with their wetsuits and surfboards on the subway?” he asked. “To relax!” Then, he kindly directed us to beach 94. The beach was empty. Mik and I couldn’t stop smiling—we felt like we were playing hooky. We surveyed the vast Atlantic, and breathed.

The portrait I made of Mik at the waterline captures that repose. But to my eye, it also looks uncannily like the Andrew Wyeth painting, Christina’s World. The resemblance lies in the nuance of shadows and light, the waving grass, my subject’s backward-facing posture, and the property on the horizon line (in this case, a Mitchell Lama housing complex rather than a farmhouse) that appears imperiled by a looming, unseen force.

The sign sits on the new $341 million concrete boardwalk, built to replace the wooden promenade wrecked by Sandy. “CLIMATE CHANGE IN EFFECT,” it warns, in Russian. The more resilient boardwalk has been built at a higher elevation, with sunken steel pilings above a retaining wall designed to keep sand from being pushed into the streets.

Rockaway was among the New York City communities hardest hit by Sandy. When the hurricane slammed into the unprotected peninsula, flooding it with a fifteen-foot storm surge, the old boardwalk was ripped from its moorings to smash into beachfront properties, a raging six-alarm fire took out some 100 homes in the area of Breezy Point, another blaze decimated a commercial block, and power was down for weeks. The nearby Rockaway Wastewater Treatment Plant was out for three days, during which hundreds of millions of gallons of raw sewage were released into the waterways—a gross example of why the city must retrofit its wastewater facilities for higher tide levels, to avoid drowning in its own shit.

Post-Sandy, the federal government replenished Rockaway Beach with enough sand to fill the Empire State building twice. An Army Corps of Engineers project has proposed to build eighteen-foot reinforced dunes and thirteen new jetties along the peninsula to help stockpile more sand, which would mitigate the force of storm tides on the beachside, and on the bayside, a $3.6 billion system of levees, gates, and floodwalls to control the level of water. Some blue-collar residents along the Rockaway rail line across Jamaica Bay have used funds from the city’s Build It Back program to raise their houses higher up on stilts. But the Rockaways were built on a sandbar that geologists have argued should never have been developed in the first place. A troubling amount of restocked sand on Rockaway Beach has already been eroded by the relentless action of the waves. Outside my picture’s frame, the sun-dazzled ocean kisses up to the dunes at narrowed parts of the shore, caressing the beach up as far as the new boardwalk.

How to reconcile these twin feelings of pleasure in the city’s enjoyments and terror of its threats? I have learned that the world is running out of sand; that every second we’re adding four Hiroshima bomb’s-worth of heat to the oceans. I think of an hourglass. I think of my kids. But for now, being hungry, Mik and I set out for lunch.

Visiting the seventh sign, Mik humored my kids by agreeing to wear a Halloween mask in St. Nicholas Park. The mask is from the production of an adaptation of Macbeth called, “Sleep No More.” My kids were in costume, too. I brought them along on our errand to reckon with the climate sign after their school’s Halloween parade. The boy was dressed as a killer scarecrow, and the girl, a ninja. I was their mama wolf.

After I shot Mik looking like a nightmare in the mask with no mouth, standing before the sign that originally caught my attention, he was sweet enough to borrow my iPhone to make a family portrait of us. The kids were oblivious of the sign, using the park for its highest purpose—play. They could not keep still. Outside of the frame, they collected acorns, poked sticks in the mud, and tumbled joyfully down the hill.

Not far from here in West Harlem is another park, where their father and I take the kids ice-skating in winter. It’s spread alongside the Hudson River above the North River Wastewater Treatment Plant, where the pumps are receiving an upgrade as part of a renovation to improve climate resilience. From the skating rink, you can see the plant’s exhaust stacks rising like a pack of tall white cigarettes. When the wind is strong, it smells of rotten eggs. Recent air samples from the site showed levels of formaldehyde that exceeded guidelines established by the city’s Department of Environmental Conservation, raising the ire of environmental justice groups fed up with the chronic placement of toxic and hazardous waste sites in low-income black and brown neighborhoods.

Formaldehyde, which has been linked with cancer, can be created by incomplete combustion of methane gas produced during the process of wastewater treatment. Molecule for molecule, methane’s a stronger greenhouse gas than CO2, though it’s less abundant in the atmosphere. Its main human-derived sources are agriculture, such as cattle-farming, waste (such as from landfills), and the fossil-fuel industry. “Really, the best thing you can do to save the planet is to kill yourself,” joked a stand-up comedian I had seen at a club in SoHo with a girlfriend the night before. “The second best thing is to stop eating beef.” The Earth has as much as six times more methane concentration in the atmosphere than before homo sapiens emerged. With the thawing of the permafrost regions of the Arctic, more methane is being released. My kids are at the age where they love fart jokes, but as funny as I found that comedian, there’s not much to laugh at in this.

The sign stands high above Mik on the bluff toward Sugar Hill. Uptown, we’re rolling in hills, some so prominent that they grant sweeping southern views of Manhattan, razed in the nineteenth century of its forests, farms, rocks, and slopes to create the rectangular grid. Back when my son was obsessed with violent weather and I told him we were safe in the Heights, he understood it was an evasion. We aren’t disconnected from the other parts of the city, just as our country isn’t disconnected from the other parts of the world.

In the silent white mask, Mik faces the entrance to the 135th Street subway at the bottom of the slope. The B stops here, and the C. The subways are the blood vessels of our body politic. Even at three, my boy understood this. It’s hard to imagine what the city would be like without its trains should flooding disable the system altogether; what the spire of the Empire State building in midtown would look like from the rump of Sugar Hill—a buoy? I can’t help wondering what the city will look like to our kids when we’re no longer here.

At night, when I tuck in the girl, we play a game. I ask if she knows how much I love her, and she replies in the following ways: infinity hundred infinity, more than all the world’s worlds, long after you’re dead, and I’m dead, and the world is dead, too. To each reply, I answer, “More.” Maybe motherlove is a hyperobject, but so, Guariglia has told me, is climate change. For all the ferocity of my love, I’m powerless to protect my kids from the mass extinction we’re in the midst of that could eliminate 30–50 percent of all living species by the middle of the twenty-first century. Why is this not the core of the core curriculum? Why aren’t we all speaking about this?

Mik told me that the first user-generated question that came up in his search for St. Mary’s Park in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx was about safety. The sign on a hilltop across the dog run was defaced with graffiti. Two dicks spouting cum and the dictate “Eat my ass,” competed with Guariglia’s flashing warning signals: “FOSSIL FUELING INEQUALITY,” “CLIMATE DENIAL KILLS.”

“FUCK YOU!” someone had also scrawled on the sign’s orange base, which was surrounded by trash. Maybe teenagers had done it, like the two girls passing behind Mik in my photo. I like to think they wouldn’t have, had the art offered comfort or beauty, or had the sign been useful in a practical sense. But in the context of the southeast Bronx, where failing infrastructure is a fact of life, the graffiti read to Mik and me like an act of protest against the hazard sign itself.

It would have taken me four trains to get here from Upper Manhattan, though it isn’t far as the crow flies, except that the third train wasn’t running to carry me to the fourth, and so I got off at Yankee Stadium and walked three miles to reach St. Mary’s Park—past the Bronx County Court House, through the Melrose Housing Projects, and behind a trans woman in fabulous leggings printed with silver skulls, who clutched at her toothache on her way to a storefront dental clinic, moaning, “Why is the demon bothering me, why?”

Last week, single-use plastics were banned by the European Parliament, while the news came that the sea is absorbing far more heat than we’d realized, and that it’s too late to save the Earth by planting trees. Even if we covered the planet with trees, it would be too late. It is already broken. Another sign appeared in my feed. This one taped in the window of a bookshop in Cornwall, England: “Please note: The post-apocalyptical fiction section has been moved to Current Affairs.”

The densely-packed Bronx is the poorest of New York’s boroughs, making it more vulnerable to heat of every kind. It isn’t easy for the people who live here to leave. What does it mean, in a neighborhood where many forces choke possibility and freedom of movement itself is restricted by transportation that fails on the regular, to be told that climate denial kills? When we suffer an untreated toothache, the pain is so immediate that we can think of nothing else.

At Hunts Point, two stops closer to the waterfront on the 6 train, Mik and I discovered after crossing beneath the busy Bruckner Expressway, that the sign in Riverside Park was blank. Its solar battery had been jacked, the master lock popped, the orange encasement flung open like the lid of a pilfered jewelry box. We were impressed by the thief’s enterprise in recognizing the battery’s value. When I shot Mik sitting beneath the black screen, I felt curiously relieved by the sign’s defacement, its silence. By this time, at the ninth site, I had memorized the looping messages of the hazard signs, and could focus instead on the graceful posture of my friend, who’d opened his coat to enjoy the sun; the sludge of the Bronx River behind him, and the projects on the opposite shore.

Riverside Park is a little park, covering just 1.4 acres, a Faulknerian “postage stamp of native soil.” Once a vacant lot and illegal dumping site, it’s the first of a planned string of parks to be linked by a bike route as part of the developing South Bronx Greenway. Behind Mik is a fishing pier and canoe launch. I’ve been here before with my kids to ride rowboats in the summer when folks inflate bouncy castles for the kids, hold all-day barbeques, and pump Nineties hip-hop from big sound systems. Although we’re now deep into the fall and the only ones here, today is freakishly warm at 67 degrees.

Extreme heat is a dangerous element of our changing climate. It kills more Americans per year than any other weather related event. Cities are often 2–8 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the areas that surround them because of the urban heat-island effect. At night, when our bodies need to recuperate from stress and heat, the contrast in temperature is more extreme—ranging as much as 22 degrees. This is due to urban design—our tall buildings, black rooftops, and dark pavement, which attract and absorb the sun’s rays.

A 2013 Berkley study indicated that people of color are up to 52 percent more likely to live in urban heat islands than white people. We face more health risks during heat waves as a result. What’s more, long histories of under-investment in black and brown urban neighborhoods have made our communities heat up more and faster overall than the already hot cities we live in. Hunts Point has one of the city’s highest rates of heat-related fatalities. 98 percent of its residents are people of color. The NYC Environmental Justice Alliance has made addressing the urban heat-island effect its top priority for climate justice because, while hurricanes and storm surges may smack us every five or more years, we can count on extreme heat to clobber us every single summer.

According to a 2018 article in Grist by Justine Calma, New York City sees a yearly average of 450 heat-related visits to the ER and over 100 deaths attributed extreme heat, but the Environmental Justice Alliance estimates the actual death toll to be a lot higher—depending on the variable criteria different researchers use to link deaths to heat waves, the annual number could be over 600. A recent Columbia University study projected that by 2080, up to 3,300 New Yorkers per year could die due to heat-related causes exacerbated by climate change. In fact, New York is one of the most vulnerable cities in the developed world to the threat of urban heat.

The Hunts Point peninsula is an example of a hotspot within a heat island, Calma writes. It’s a heavily industrial neighborhood where residents, who make, on average, $22,000 a year, often live in packed apartment buildings with more heat-trapping surfaces and fewer green spaces to help cool the neighborhood. Who can afford an air conditioner on $400 a week, let alone the higher electric bill to run it, when there is rent to be paid?

The New Yorkers most at risk of heat emergencies live in fence-line communities of color like this one, burdened by decades of polluting infrastructure as well as poverty. For a long time, Hunts Point had one of the lowest parks-to-people ratios in the city, but over the past decade, locals have lobbied for more green space along its riverfront, like this one. To the left of my frame is a salvage yard heaving with crushed cars and scrap metal. At my back, across some railroad tracks, an idling produce truck is unloading cartons of ripe pineapples and strawberries. Hunts Point works as both mouth and ass for the city, getting food in, taking waste out: this neighborhood of 13,000 people has the world’s largest wholesale produce market and over a dozen waste transfer stations. Along with the rest of the South Bronx, it handles nearly a third of the city’s solid waste. Meaning, there are trucks everywhere, all the time, piping out hot exhaust, heightening the risk of asthma attacks, and further broiling the air.

The city’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency recently launched a “Cool Neighborhoods Plan,” to partner with grassroots organizations in efforts to mitigate the health risks of extreme heat in vulnerable communities. Strategies include painting surfaces white, planting trees, checking on older people who might be housebound in stifling apartments, greening roofs, and getting out the word about cooling centers—public air-conditioned facilities like libraries, community centers, and senior centers, where folks can cool off for free. City officials piloted the initiative in three neighborhoods last summer, including Hunts Point. Without whole-cloth citywide initiatives toward cleaner energy, hotspots like this could be feeling summer days that are 15 percent hotter than today by the 2080s. Can you even imagine a 120-degree day? In the cities of New Delhi, Baghdad, Khartoum, Mexicali, and Phoenix, they’re already there.

The unspoken threat remains in the frame, as does the tension between the sign, the human, and the landscape, but all the same, it was another beautiful afternoon for walking the city. Later on, I took my children trick-or-treating without need of their jackets.

The following week, Mik and I visited the tenth and last sign. We rode the Staten Island Ferry to get us closer to Snug Harbor, where the sign was stationed. It was the day before midterm elections, and gently raining. The air held an elegiac mist with an electrical charge: leaning over the ferry’s wet rail, it was impossible not to conjure Walt Whitman thinking about us “ever so many generations hence.”

“Whitman was one of my gateway drugs to literature, and these days I have such a hard time connecting to his voice, optimism and vision of America,” Mik admitted. “How hard it is now to have faith that future generations will even exist.” We regarded the Statue of Liberty in a shawl of fog, and Ellis Island.

Climate change has become an often-unspoken contributing factor driving recent waves of immigration, such as the Central American migrant caravan used by the right-wing media to stir up ire as it neared the Mexican border. Mik grew quiet looking out at the white wake of passing ships. Patrol boats, skimmers, tugs, barges, the ghosts of whalers and steamers, and the ocean liner Queen Mary 2. I asked what he was thinking about.

“The wildfires in California,” he said, and all those fleeing fire, “but also how many more of us will be climate refugees in our own lifetime, all because folk turned greed into an economic system a few hundred years ago.”

Belying his justifiable pessimism was the fact that Mik had just returned from Georgia, where he’d volunteered to drive elders without transportation to the polls for early voting. Understandably, he was nervous about the direction our country would go. There was a larger national anxiety about the feasibility of a “blue wave”—a Democratic sweep to win back the House. “I don’t believe it,” President Trump said of his own administration’s November report, which stated, “climate change is transforming where and how we live.” In the Republican stronghold of Staten Island, a borough known for voting against its own environmental interests, it cheered us somewhat to observe Democratic congressional election signs staked in the front yards of North Shore houses on the bus route to Snug Harbor.

Snug Harbor has been referred to as Staten Island’s “crown jewel.” People get married and shoot films there. Once a retirement community for aged merchant sailors, it’s now a National Historic Landmark District set inside an eighty-three-acre park that runs along the Kill Van Kull tidal straight. Mik and I wandered among lush gardens freakishly still in bloom, a duck pond, a fountain memorial to local rescue workers who lost their lives on September 11, a farm, a surreal field of brightly colored lanterns including the giant head of a dragon, and several Greek Revival, Beaux Arts, and Italianate-style buildings—a chapel, a foundry, a theater hall, a hospital—remnants of the nineteenth-century seafaring community, repurposed for the arts.

Inside one of these stately buildings, now operating as a museum, we found Gus, a maintenance worker built like a fire hydrant, who bragged about Snug Harbor with charming civic pride. He was grateful to Jackie Onassis for her part in preserving the site and was glad to share its history with other New Yorkers—who, he admitted, tend not to visit the borough because it’s difficult to access, and because of lingering bad PR over the Fresh Kills dump that grew, over the second half of the twentieth century, into the biggest manmade structure in the world.

Mik asked if the maintenance crew was doing anything particular to protect the landmarked buildings from sea-level rise. Not that he was aware of, Gus said. “Like most New Yorkers, we only think about that stuff when it’s too late.”

On the subway map, Staten Island looks small and somewhat neglected, an afterthought boxed in the lower left-hand corner like a leftover chicken nugget. In reality, it’s huge—over two and a half times the landmass of Manhattan—nearly as sprawling as the borough of Brooklyn. Situated in the crook of the New York Bight, the island suffered more than half of the city’s forty-three deaths during Sandy, bearing the brunt of a storm tide that peaked here at sixteen feet.

Gus talked about the southeast shore of Staten Island, specifically the wooden bungalow community of Oakwood Beach hit by the superstorm’s worst flooding in a funnel effect that left some clinging to their rooftops while others drowned in their basements, trying to fix their sump pumps. That part of Staten Island is now rewilding with grasses, flowers, insects, possum, deer—returning to a natural wetland state. Most of the homes there were demolished after property owners took buyouts from the state government, choosing to relocate rather than attempt to rebuild—one of few examples in the city of managed retreat. As our coastlines become increasingly unlivable, this kind of deliberate migration away from the water’s edge may grow more commonplace. In the meantime, a breakwater project is underway around the south shore to protect those stalwarts who remain, seeding oyster beds to prevent coastal erosion and absorb wave energy while cleaning the water, while the Army Corps is planning a $580 million seawall that many scientists claim would ultimately fail.

“Humans are stupid,” Gus shrugged. “We want what we want, even when it don’t make sense.” He urged us to return to Snug Harbor for the winter lantern festival. He’d mistaken us for a couple. In a platonic sense, I guess we were. Ours was a marriage of inconvenient truth. I couldn’t show a face of fear to my family, and so I showed it to Mik, who held my gaze without judgment, and looked right back. Even though I knew I’d see him again, I felt a little sad that our assignment was ending. I enjoyed his company, and our journey gave structure to my scattered thoughts. The rain was growing heavier and so we took cover under a gazebo.

In our final portrait, Mik takes his hair down and folds his arms protectively over his middle. He looks older to me than he did in September, when we met by the first sign. “La terre est bleue comme une orange…” The world is blue like an orange. Orange is a color that strikes you in the gut. I am struck by the orange dominating this picture, turning it nostalgic. The traffic cone, the fall leaves, the gazebo walls, the base of the road sign, the text, and even the undertone of Mik’s skin appear orange beneath the thunderclouds. The warm orange of autumn integrated with the bright orange of hazard.

“VOTE ECO-LOGICALLY,” warns the sign, approaching its target.

The next day, a lot of us did just that. Bronx-born Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the democratic socialist who was voted to represent New York’s 14th congressional district, has just posed the Green New Deal, which aspires to cut US carbon emissions soon enough to attain the Paris Agreement’s most ambitious goal: preventing the world from warming any more than 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100. “This is going to be the New Deal, the Great Society, the moon shot, the civil-rights movement of our generation,” the young congresswoman said at a Town Hall meeting a month after the election, drawing on the cocky attitude of American exceptionalism. Who am I to say “too little, too late,” when she’s supplied me with the script to motivate my children with this rallying cry: “The only way we’re going to get out of this situation is by choosing to be courageous.”

I heard the same conviction in Justin Guariglia’s voice when I interviewed him about his art. He described what it felt like to photograph the Arctic meltdown from the troposphere with a mixture of emotions: fragility, urgency, anxiety, awe—the simultaneous contraction and expansion of self that Whitman sang about. “You sense your own insignificance and the sublime,” was how Guariglia put it.

My route with Mik across New York felt like a less glorious, though still noble, version of that crossing. I hold in my mind a new map of the city as a vulnerable and precious entity, both larger and smaller than I had understood, an appreciation of the water that binds us, gratitude for the prize of a friend I didn’t have before, (worth infinitely more than the tote bag bestowed by the Climate Museum) and the sinking realization that, eventually, we may have to migrate. Finally, I learned an altered sense of time, which I’ll describe by paraphrasing the philosopher whose work inspired the climate signs that led us down a soft pathway out of silence into speech: we must awaken from the dream that the world is about to end; action depends on our awakening. When did the countdown begin? Let us reconsider the clock. Morton theorizes that the world has already ended. The ball dropped in 1784, he writes, with the advent of the steam train and the resulting soot that indelibly marked our footprint on the Earth’s geology during our swift carriage into the Industrial Revolution.

I think of the romance of the train, the iron horse that collapsed time and distance even as it began to undo us. How well my boy once loved trains. That boy is no longer here. In his place is another. In Mik’s picture, my son stands as tall as my shoulder. Fittingly, for a kid whose latest passion is monsters, his favorite holiday is Halloween. At first I begged him not to chew Mik’s ear off about supervillains from the Marvel universe and the darker actions of Greek Gods. Then I stopped myself, and thanked my boy for his morbid curiosity. He is teaching us to pay attention. The signs hint at violence. I like how he and his sister are dressed in the context of the sign’s bad news. CAUTION. The boy wields a scythe. The girl wears a katana tucked in her belt. She is stealthy; he is fierce. They look strong and alert. Good. They will have to be brave for the roadwork ahead.