Her name was Laure. She is recorded as a resident in the property books of 1862, paying two hundred francs for a room on the third floor of 11 rue Vintimille, an industrial building that had been partitioned into rental spaces. In Olympia (1863), one of three paintings by Édouard Manet for which Laure modeled, she looks toward the reclining nude courtesan expectantly, with a bouquet of flowers wrapped in paper. When Olympia was first displayed in the salon of 1865, very little mention was made of the black female figure in it, aside from several racist caricatures in the press.

Despite the fact that this oversight exists in most of the art-historical literature on Olympia, slowly Laure has emerged, particularly after art historian Griselda Pollock’s 1999 Differencing the Canon, based on archival research by Achille Tabarant, identified Laure as Manet’s model from a small notebook of the artist’s dating from 1860–1862: “Laure, très belle négresse, rue Vintimille, 11, 3ème,” the painter wrote.

“Black Models: From Géricault to Matisse,” at the Musée d’Orsay, builds on this kind of archival research to recover the biographies of models of African descent in canonical French painting. While Olympia, often considered the first modern painting, plays a central role in the exhibition, its scope, as the subtitle suggests, reaches far beyond that tableau. The show chronologically traces the depiction of black figures in French painting from the revolution to the mid-twentieth century.

Archival material from libraries and collections around the world and paintings gathered from both the permanent collection at the Orsay and loaned from other museums expand the scope and size of the show’s preceding iteration at Columbia University last winter, where it was titled “Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today.” Developed from curator Denise Murrell’s 2013 doctoral thesis at Columbia University, which argued that blackness and black people played a central part in how we picture modernity, the original exhibition explored the role of black models in modern painting.

In this Orsay version, the word “model” is used loosely and inclusively. The show represents professional models, many of whom were formerly unknown, such as Madeline or Laure, as well as better-known figures like Alexandre Dumas, Josephine Baker, and Ady Fidelin, the first black fashion model to have her picture published in an American magazine. Rooms are grouped thematically and progress chronologically through “nine chapters,” each focusing on the biographies of different models.

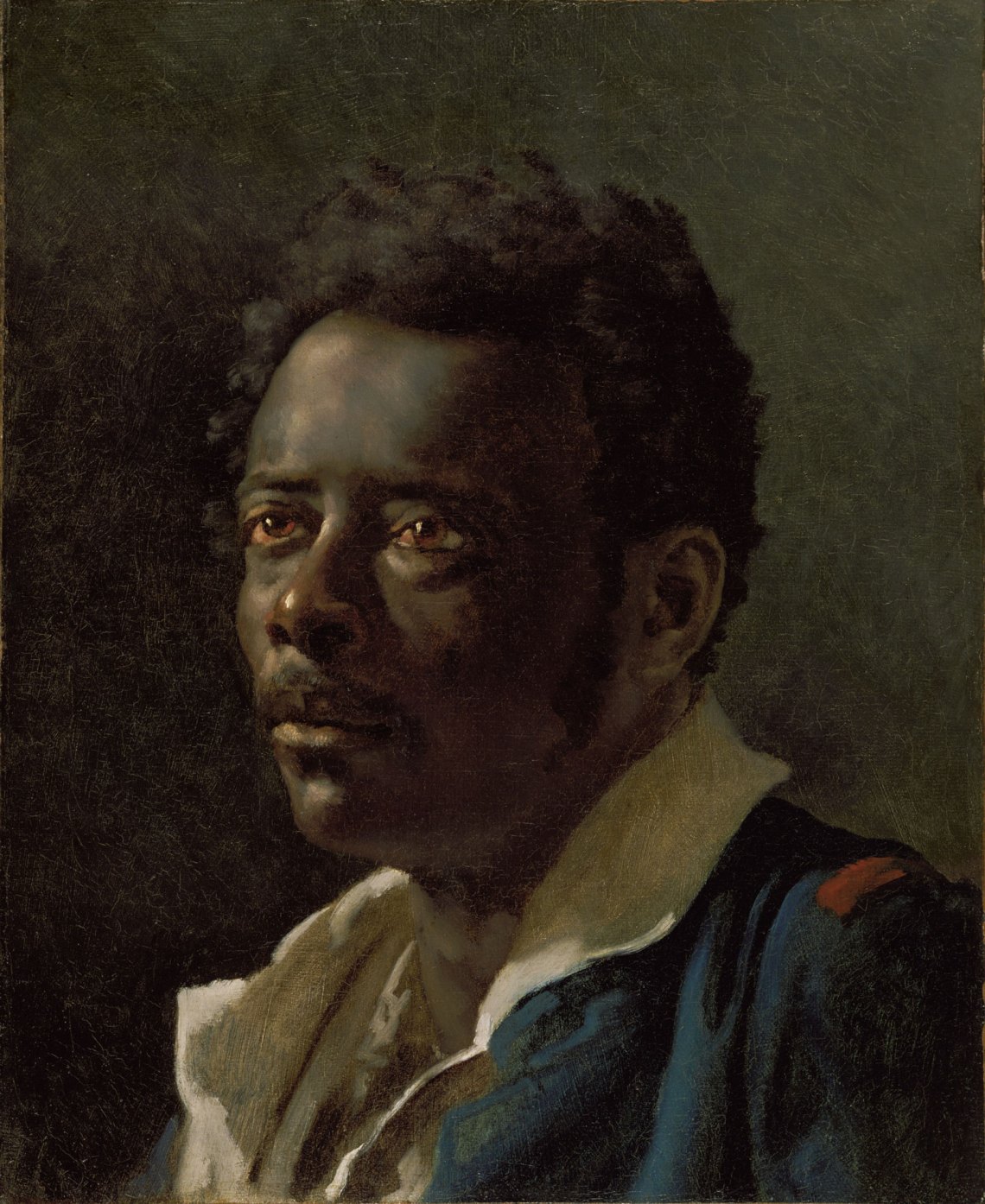

One of the more surprising elements of the exhibition concerns its titles. In cases in which a painting’s title fails to name its sitter, such as the first portrait displayed in the exhibition, Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of a Black Woman (1800), the exhibition titles the work Portrait of Madeline. In the catalog, art historian Anne Higonnet explains that because the title had already changed from une négresse to une femme noire, altering it again only furthers a process of rectification. Higonnet further remarks at how odd it would seem to many if Mona Lisa was titled “Portrait of a white woman.” And alteration is less anachronistic than it may first appear: titles of artworks, even Manet’s portrait Jeanne Duval (1862) included in the exhibition (known alternately as Baudelaire’s Mistress, Reclining as well as Woman with a Fan), have changed for far less pointed reasons. Giving Madeline her name reflects the dignity afforded most affluent sitters at the time.

Unlike in the United States, where a more mainstream discourse on race, slavery, and the slave trade has developed in recent years, in France the legacy of slavery and colonialism is less frequently addressed. Slavery was abolished in 1794 during the revolution and reinstated in 1802 under Bonaparte. And though the slave trade was again ended in 1815, slave-holding remained legal in French colonies until 1848. Portrait of Madeline exemplifies this complicated history: according to art historian Anne LaFont, Madeline was a freed slave from Haiti who lived an emancipated life during a time when enslavement had been reestablished overseas. She had been hired as a domestic servant of the painter’s in-laws. Displayed in the same section of the exhibition as the original 1794 declaration of the abolition of slavery, the portrait is no longer an allegory for race, or a formal study, but a depiction of an individual at a fundamental moment in history.

Advertisement

More than a project to uncover the identities of the unnamed subjects, “Black Models” inverts how biographical research is put to use. Here, instead of being a tool to study the artist, biography of black figures opens the artworks to reinterpretation. The achievement is threefold: a chronological study of black figures in French painting from the revolution to the postwar period, a restitution of the identities of black models and sitters, and an insistence on bringing a new parity to critical accounts of black and white subjects in historical paintings.

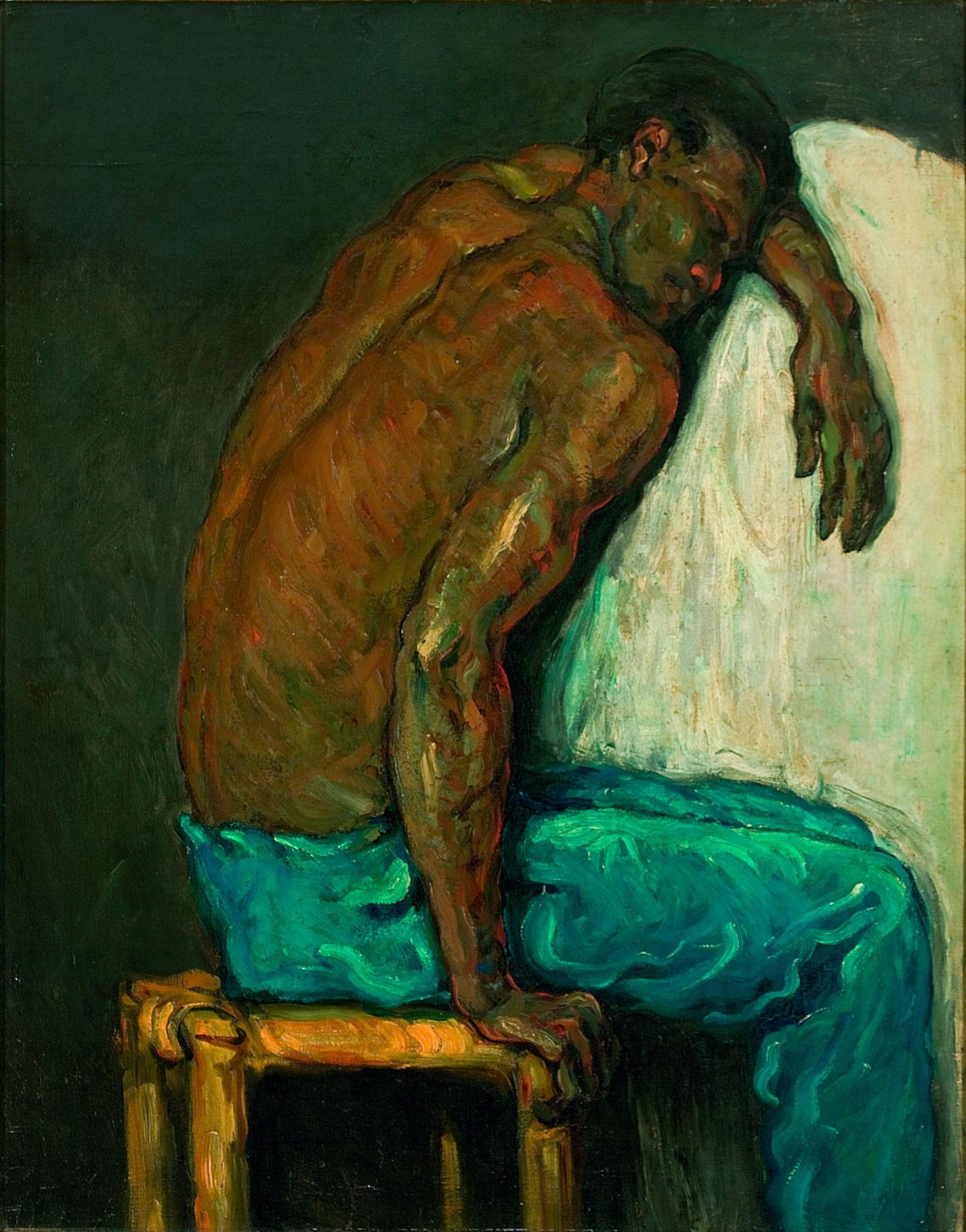

And Madeline is obviously far from the only case in point. A man named Joseph, also born in Haiti, around 1793, became one of the most well-known models of his day, originally gaining a reputation in Théodore Géricault’s 1819 The Raft of the Medusa (only an early study of it is on display; the painting itself is held by the Louvre). Joseph was hired by the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where he worked from 1832 to at least 1835. An illustration of Joseph even accompanied the entry on “model” in Larousse’s Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle. Archival materials, such as the ledger that registers him at the Beaux-Arts in 1832, are presented alongside tableaux and drawings, such as Géricault’s Study of a Man, After the Model Joseph (1818–1819).

An entire wall of images of the great novelist Alexandre Dumas, including both racist caricatures and more stately photographs by his friend Nadar (pseudonym of Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) indicate how much the writer’s mixed heritage factored into his public reception. And yet that history has apparently been minimized over subsequent years: a French friend at the exhibition’s opening expressed surprise to discover that Dumas was, in fact, black. Dumas appears in a section titled “Literary Mixes,” along with the actress Jeanne Duval, Baudelaire’s romantic partner for nineteen years (Nadar, in fact, was withBaudelaire when he first saw her perform). Her abovementioned portrait by Manet is displayed next to Baudelaire’s sketches of her.

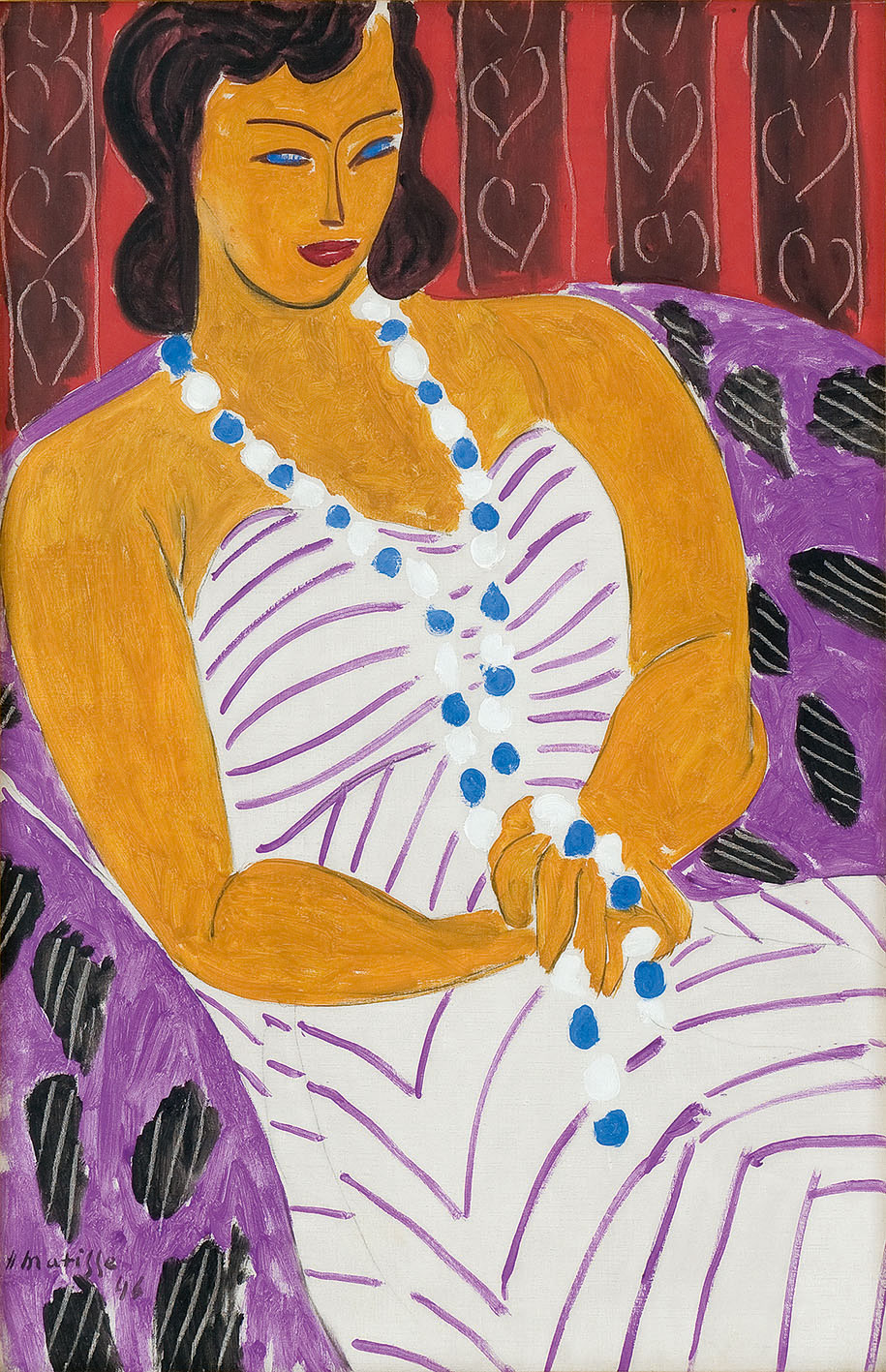

In a few cases, the black model remains shadowed by the white artist. Near Baudelaire’s drawings of Duval are works by Henri Matisse from his 1947 artist’s book edition of Les Fleurs du mal. Here, Matisse’s images of Carmen Lahens, a Franco-Haitian actress who was famous in Paris during the 1930s, correspond to Baudelaire’s poems apparently written for Duval.

Later, the section “Matisse in Harlem,” which chronicles the artist’s visit to New York in 1930, presents a fascinating series of photographs by Carl Van Vechten and James Van Der Zee depicting life in the cultural mecca, alongside works by Matisse, such as his 1947 book Jazz, as well as two wonderful portraits featuring Elvire Van Hyfte. Yet here more emphasis is placed on the biography of Matisse than the life of Van Hyfte, a Belgo-Congolese woman who studied philosophy and kept a lengthy correspondence with the artist.

In the final section, “I Like Olympia in Blackface,” a title taken from a Larry Rivers painting, an attempt is made to adjust historical imbalances that the exhibition explores, gathering a small suite of responses to Olympia by modern American artists, including Romare Bearden and William Henry Johnson. Yet where the show further expands on its premise is outside of the exhibition proper, particularly in relation to the question of biography. On the far towers in the main hall of the Orsay, in bright neon, Glenn Ligon’s Some Black Parisians (2019) is part of a series of commissions by the Orsay to put contemporary artists in dialogue with the collection.

Ligon installed the names of twelve historic black Parisians in lights, modeled on the shape of the individuals’ signatures, in the cases where they are available—many of them subjects in “Black Models.” Ligon’s work seems particularly fitting in Paris, the city which saw the first neon, alighted in 1910. Some Black Parisians provokes us to further reflect on how much more needs to be done: the names are in front of us, and yet many museumgoers neglect to look up. A few days after the opening during a discussion at the National Institute for Art History, Ligon remarked that the work’s visibility was not unlike Laure’s initial critical reception: “They stand under it, they see it, but some of them clearly don’t see it.”

“Black Models: From Géricault to Matisse” is at the Musée d’Orsay through July 21.