On September 20, 2016, police officers in Charlotte, North Carolina, arrived at the apartment complex of a forty-three-year-old black man named Keith Lamont Scott. Searching for a different man with an outstanding warrant, the police happened upon Scott in his car, where they claim they saw a blunt and a gun. They ordered Scott out of his car, and when he got out, Officer Brentley Vinson fatally shot him, as Scott’s wife looked on, screaming in horror. He would later say Scott was holding the gun they said they’d seen.

The shooting came on the heels of so many others like it—Michael Brown Jr., Philando Castile, Tamir Rice—that it went virtually unremarked that the police officer who killed Scott was also black. Devastated protesters gathered on the streets of Charlotte to cry out against another black life lost in a police-involved shooting. Facing off against rows of cops in riot gear, they chanted, “Hands up, don’t shoot!” and “Black Lives Matter!” They marched for three days. Some of the protests turned violent, and another man lost his life.

These events, unfolding in a sequence that feels all too familiar to us now, seemed to encapsulate once again the grim reality of race relations in America in the twenty-first century: the hopeless division, the animosity, the disregard for black lives, and the distrust in police forces increasingly viewed as the law-and-order wing of white power. But forty miles northeast of Charlotte, God was trying to write another story. That, at least, is how Pastor Derrick Hawkins sees it.

Pastor Derrick lives in Salisbury, North Carolina. A tall, striking black man with wide set brown eyes, Pastor Derrick has a long goatee that he strokes when he gets lost in a thought. He has an intense charisma, coupled with a deep-seated humility and a hungry, restless mind. He is one of those people who becomes the focal point of every room he’s in, no matter who else is there.

At the time of Keith Lamont Scott’s shooting, Pastor Derrick was thirty-two years old. He was in the process of taking over the leadership of a black evangelical church in Greensboro, North Carolina. The church, the House of Refuge, was located just a few miles away from an old Woolworth’s, where, in 1960, four black college freshmen sat down at the whites-only lunch counter and refused to leave. Six months later, the store, losing money fast, was forced to desegregate. The event catalyzed a wave of sit-ins across the nation that contributed significantly to public support for the Civil Rights Movement, crucial to its success.

Despite that landmark, though, this cradle of the civil rights movement remains quite segregated. It’s why Pastor Derrick could never bring himself to live in Greensboro; he still lives in Salisbury, and commutes to the church.

The morning of September 21, 2016, Pastor Derrick awoke in his home in Salisbury to the news of the shooting. But he found out from an unexpected source, a one-line text message from a white pastor named Jay Stewart: “Did you see the news yet?”

Pastor Jay Stewart is the founder of a white evangelical mega-church located in Kannapolis, North Carolina, which was also called The Refuge; it’s how the two pastors originally met, in fact. Pastor Derrick had seen a huge red and white sign for The Refuge one day in 2015 while driving his daughter to get her hair done, and he’d been drawn to the arresting sign that bore the name of his own church. Man, that would be amazing on our church, he thought. I need to figure out who made that sign.

He called the number, and it led him to the mega-church’s main campus, in Kannapolis. He was invited to attend a service, and was so moved by the preaching, which focused on unity, revival, and people coming together, that he cried the whole way home. He and Pastor Jay started meeting regularly, forming a deep bond.

Pastor Jay, who is fifty-six but has a youthful mien, became a mentor and father-figure to Pastor Derrick. Tall, with blue eyes, thinning gray hair, and a trim beard, Pastor Jay exudes curiosity and excitement about the world around him, coupled with a soothing serenity. Their friendship was an unlikely one—a middle-aged Southern white guy who headed a white mega-church, and a young black man ministering to a flock with significantly different life challenges.

But Pastor Jay and Pastor Derrick weren’t just close. As of September 19, they were colleagues. Just the day before the shooting, they had announced that their two churches would be merging into one, with the House of Refuge joining The Refuge to become one of its campuses.

Advertisement

There had been a little resistance at Pastor Derrick’s church. “Could you not have merged with a black church?” Some asked him. Others were worried that the merger would mean that they would have to change, or would lose their identity. Their biggest concern was, “Are we still going to be able to be black?” That fear was quickly allayed by Pastor Jay’s respect for their traditions and the fact that Pastor Derrick’s church would maintain its own campus, so that the Greensboro community could keep its identity and freedom of expression. The two churches would come together for prayer, events, study groups, and community outreach, with Pastor Derrick heading out to the Kannapolis campus at least three times a week.

Meanwhile, in Pastor Jay’s church, he felt nothing but celebration. When he announced the merger, there was a standing ovation. People went crazy. “This is the heart of God,” they told him. “This is awesome.”

And then the shooting happened.

After he read the text message from Pastor Jay, Pastor Derrick looked up the news online, reading about the shooting and the protests. Wow, he thought. This is hitting Charlotte. This is hitting home.

His social media feeds were soon in uproar. People were distraught, drawing parallels with the other recent police-involved killings of black men and boys across the nation. That day, Pastor Derrick planned to lunch with the white pastors whose church had just merged with his own. When he showed up, the first thing Pastor Jay asked him was how he was doing, and how the shooting was affecting him.

“Man, I know I haven’t walked in your shoes,” Pastor Jay said, “but I at least want to understand the pain that you and that your community are going through.”

It was in that conversation, amid the racial tensions escalating around them, that Pastor Derrick realized that he and Pastor Jay were being called to tell a different story, that their relationship, guided by the spirit of God, was where a new America would be reborn.

This was not to deny America’s continuing struggle to combat racism. But Pastor Derrick realized that the equality his people so desperately sought would only come through getting out of one’s echo chamber, through building relationships.

To many religious people, there’s no such thing as coincidence: Pastor Jay and Pastor Derrick felt acutely the prophetic nature of their union taking place just the day before the shooting. It felt as though, in the midst of the chaos and the confusion, God was using them to write a better story. The Lord had guided them to their merger at exactly the right time to redirect the anger and pain in the community to a higher, holy purpose.

“What we’re doing in this moment is leading that change through a nation that’s hurting,” Pastor Derrick said, the day after the shooting. “It’s really not a race war. We just have to see the bigger picture of what God is doing. So we’re merging together what heaven will look like.”

The union of the two churches could shake the nation, Pastor Derrick believed. He and Pastor Jay, hand in hand, had been to the mountaintop. They knew what the Promised Land looked like. Together, they would build it on earth.

*

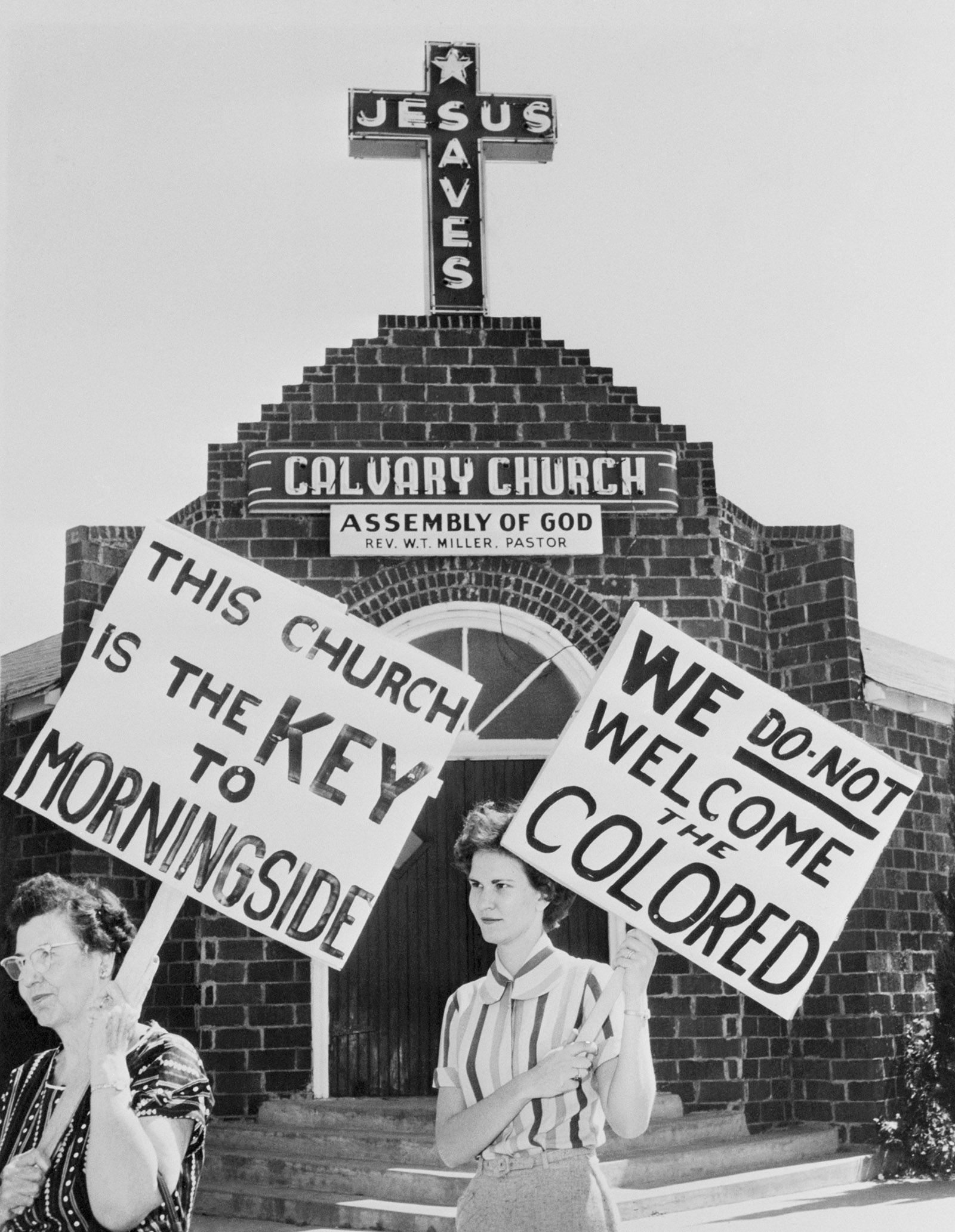

It is an enduring fact of American life that church worship remains deeply segregated. It was something that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed, just five days before he was assassinated. “We must face the sad fact that at eleven o’clock on Sunday morning when we stand to sing ‘In Christ there is no East or West,’ we stand in the most segregated hour of America,” he said at the National Cathedral, Washington, D.C., on March 31, 1968.

Dr. King was not exaggerating. Little had then changed since a 1948 survey estimated that of eight million African Americans who were affiliated with a Protestant church, 7.5 million belonged to black denominations; of the half-million who did not belong to predominantly black denominations, 99 percent were in totally segregated local branches of national denominations. Just one tenth of 1 percent of black Protestants worshipped in white churches (Catholic churches had a slightly higher rate of integration, but mainly because there were so few black Catholics).

More recent data shows that not much has changed even in recent decades. A 1998 survey found that 69 percent of all congregations were almost all white, and 18 percent were almost all black; in effect, only about 10 percent of American churches could be considered integrated. A New York Times analysis from 2000 found that 90 percent of whites said there were few or no blacks at their religious services, with 73 percent of blacks reporting the same. Most recently, a 2012 National Congregations Survey found that eight in ten American congregants still worship at a place where a single racial group makes up at least 80 percent of the congregation.

Advertisement

What could possibly explain the persistence of segregation among worshipers of the same faith? Certainly, racism plays a role, as Dr. King pointed out. The first black church, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, was formed in 1787 after a black worshiper in a white church unwittingly sat outside the pews that the white church had designated for blacks. White church elders tried to drag him off his knees and out of the pew, unsuccessfully. At the conclusion of the service, however, the black worshipers left en masse and set up their own church.

“There are lots of examples of blatant discrimination like that that did amount to the forceful exclusion of blacks as equal participants in churches, so many blacks went and started churches of their own,” explains Robert Vischer, dean of the University of St. Thomas School of Law, who has written about segregation in American churches.

Still, it wasn’t always about black people being forced out of churches. Just as often, they have withdrawn for their own reasons, Vischer explained, like having a different theological emphasis to their worship. But even theological differences often circle back to racism: whites and blacks came to emphasize different theological aspects due to their radically different experiences of America. “Whites were traditionally emphasizing the Christian message on duty and compassion toward others and caring for the community, messages that would resonate with folks who had the privilege of resources and power within society,” he told me, “whereas black churches developed more local points along the lines of solace and comfort and the promise of God’s salvation in the coming kingdom.”

And, of course, the prevalence of geographic segregation in America is a huge factor in church segregation. “If you’re going to services in your area, most areas aren’t integrated,” he said. “I do think there is a comfort level that arises when it comes to something as intimate as worship, so it is a scandal that our comfort level doesn’t seem to extend frequently to those beyond our same race. There are some success stories on this, but it does require work and intentionality. The default does seem to be folks retreating to their separate corners when it comes to worship.”

Exactly how much of church segregation can be explained by systemic racism and how much by self-segregation, based on social norms and values, is a point of contention among observers. “It’s not about racism, as much as self-determination,” argued Pastor A.G. Miller, the pastor of Oberlin House of the Lord Fellowship in Ohio, who has written two books about Christianity in the African-American community. “Just because it’s segregated does not necessarily make it bad. Nor because it’s integrated does it necessarily make it good.”

When a black church and a white church merge, major questions arise, Pastor Miller explained. “Who blends into whom? Who is transformed by whom?” For black worshipers thinking about joining a white church, other questions arise: Can they see themselves becoming the pastor of this white church? Would white people follow them? Too often, “it’s black people bending to white people,” Pastor Miller noted, “rather than white people willingly committing to change their culture to accommodate and to blend and learn from black church traditions.” There’s often an unexamined paternalism that black churches and black churchgoers experience from white churches and their worshipers. “It’s kind of an unexamined white supremacy that assumes: ‘My way or the highway. We have the best way. We’re merging with this group in order to help that group, not because we think we can learn something from them and help to transform ourselves.’”

Speaking to Pastor Miller explained a good deal about why there had been more resistance to The Refuge’s merger from the Greensboro campus’s black community than from the Kannapolis campus’s white one. “I know, at first, people were really skeptical about it, because first of all, we were merging with a predominantly Caucasian church, so at the time, that was a big deal for us,” Tierra O’Garra, Pastor Derrick’s administrative assistant and a longtime member of the Greensboro House of Refuge before the merger, explained to me. “A lot of people were afraid because we still have racial tension and racial division in our nation now, so I think that might have stopped a lot of our community. A lot of us were afraid. We didn’t know exactly what was going to come up.”

But all that changed after the merger, Tierra said. “When we merged, and when they started to come up to our service, and when we went down there, it gave us the opportunity to say, Wow, these people are just like us,” she said. “We’re all here lifting up the kingdom of God at the end of the day: white, black, Asian, it doesn’t matter. We all have the same purpose.”

*

I knew that the story of the merger of The Refuge was a special story. But I only understood how important it was after I started telling people about it. When I picked up my rental car at the airport in Raleigh, a young woman with short, blond hair and blue eyes handed me my keys and asked me where I was going. When I told her Kannapolis, a two-hour drive into Cabbarus County, she expressed surprise.

“What’s out in Kannapolis?” She asked, with a bright smile.

“I’m a journalist,” I said, “and there’s a historically black church and a white evangelical church that merged, in the heart of Trump country.”

Her face lit up. “I have to read that story,” she said. She picked up my receipt. “I’m going to photocopy this, and keep your name close by my desk, so I can look for your story. Wow.”

As I drove the two hours to Kannapolis down North Carolina’s flat, tree-lined highways, I listened to the radio, skipping channels between the four Christian stations and the five playing country music. A song called “Whiskey Glasses” about a man drinking himself into oblivion contemplating his ex-girlfriend moving on played countless times, interspersed with prayers for President Trump and the members of Congress who were “trying their best to enact strong immigration policy.” Every once in a while, I would land on NPR, and I would hear about Trump’s latest attack on Elijah Cummings, and about the “Send her back” rally that had taken place just two hours from where I was. I increasingly began to doubt whether there could be any other story than the one everyone already knew.

I drove up to the main campus of The Refuge in Kannapolis, North Carolina. In this suburb of Charlotte, 62 percent of the population is white, and in Cabbarus County, a majority (53 percent) of voters went for Trump in 2016. (Nationally, 80 percent of white evangelicals voted for him.)

The Refuge, a huge red, concrete structure, was visible from the highway, behind a fence on which hung three big signs: “Nobody’s Perfect. Everyone Is Welcome. All Is Possible.” Turning off the highway, the road to the church, which is also named The Refuge, runs up through a gated community, past a small waterfall. The campus is large and green, with huge parking lots in front and behind the building, and another waterfall near the front door in the shape of a cross, with the horizontal piece shaped like a wave.

Inside, there is a coffee shop named The Mugshot, the proceeds of which go to The Refuge’s missions in Brazil and West Africa. There is also an entire wing for children, another for the staff’s offices (there are fifteen pastors and thirty-seven staff members listed on The Refuge’s website), a special room for first-time guests, and, of course, the huge, thousand-seat auditorium where the services are held.

Pastor Jay greeted me in his office, a bright room with a gray leather couch and wood accents. He was wearing a faded denim jacket, dark jeans, a white T-shirt, and sneakers. With framed glasses, cropped hair, and a black metal key on a chain around his neck, he looked more like a Hollywood director than a man of the church, an impression quickly dispelled by his open, eager manner.

“Batya, I’m gonna be myself, if that’s okay,” he said, when I asked him to tell me the story of the merger. “I’m really looking through the lens of the word of God, and my relationship with Jesus. There is a better narrative that I believe the Lord wants to write in our country, but I think there’s a lot of people who are trying to prevent that from happening.

“I believe we have an enemy,” he said. “I believe it’s Satan, I believe it’s the devil.

“But I think there are political agendas,” he went on, explaining that these agendas exist on both sides of the political aisle. “I think there are people who feel their political party or their personal agenda is going to benefit by keeping people divided, so I think that’s happening as well.”

Pastor Jay grew up in the deep South. He was born in 1963, the middle child of three, to a Pentecostal family in Columbus, Georgia. When he was in third grade, he remembers the schools in Georgia being integrated, which meant that instead of walking to school, he had to take a bus across town. As an eight-year-old, he didn’t really understand what was happening, or why. But he remembers the tensions that resulted from the forced integration. “I don’t resent that at all. I think it’s good! But it did pose challenges,” he said. He remembers white adults saying racist things around him, especially about African Americans.

In high school, Pastor Jay played basketball. One of the only white kids on the team, he cultivated strong friendships with the black students. But Dr. King’s observation about segregation in American religious life certainly held true in Columbus. Pastor Jay would play basketball with his black friends during the week, but then on Sundays, he would go to his all-white church and they would go to their all-black churches.

Pastor Jay, like all the people I met in North Carolina, thinks that exposure to people of different races is crucial in combatting racism. But he credited something else as the reason he felt called specifically to the fight.

“Just wanting to live my life like Christ, you know?” He said. “Jesus does not think it’s okay for us to be racist, or for us to be divided! Sorry—now I’ve gone to preaching,” he apologized with a laugh. “It’s the heart of God—it’s the heart of God! The last thing Jesus prayed before he went to the cross was for unity. So unity is a big, big, deal to God. And it should be a big deal to us.”

Unity for Pastor Jay means racial unity, and that entails fighting structural racism and inequality, fighting the vestiges of slavery, fighting for full integration of blacks and whites, at a physical, spiritual, and ultimately, national level. And joining this battle—right behind him, he confidently feels—have been thousands of white Evangelicals, of whom about four in five voted for Trump in 2016.

To some, this may appear a contradiction. It is a common belief in liberal and left circles that Trump is a racist, ergo so are those who voted for him, at some level. This view dominates much of the mainstream media commentary on our current political moment: a vote for Trump is seen as a blank check for white supremacy. But the white worshipers at The Refuge—and, perhaps more importantly, their black co-worshipers—don’t see things that way at all.

Pastor Jay didn’t want to discuss politics: he never preaches politics, doesn’t endorse candidates, and said he had no knowledge of how his parishioners voted. But I was able to pose the question of Trump to another pastor at The Refuge, Pastor Teri Furr.

“I think we’re all aware of what the struggles would be as it relates to President Trump and fully understand what you’re saying,” Pastor Teri said. “I think for us as Christians, some of the issues he does stand for, the foremost being his stance for life, and several issues like that, a lot of us are just grateful for the stands he has taken, and even some stands as it relates to Israel, that have been very different from what we’ve seen in the past.”

As Christians, Pastor Teri explained, they are called to vote for the candidate whom they see as upholding scriptural principles. “But it’s not about a man,” she explained. “To even call myself a Trump supporter, it’s not even about that. I’m a Kingdom of God supporter. I believe that the Lord has used him to lead the country in some important ways. But I also have been heartbroken over decisions he’s made.”

I asked Pastor Teri which of Trump’s decisions had broken her heart.

“Oh, don’t make me do that,” she laughed.

“But wouldn’t Jesus really object to the tweeting, for example, and feel that it’s dragging our country down, and deepening the divisions in a way that is ungodly?” I pressed. “Why isn’t that a thing to compete with, or even override, the right to life?”

“To me, it’s not a deal-breaker because he’s still a man, and whatever he’s walked through, whatever choices he’s made along the way, he’s not going to be perfect,” Pastor Teri explained. “The last thing I want to be is a Donald Trump defender. I’m grateful for the issues that I believe he’s stood for righteousness in, but some of his statements along the way, some of the things that were really disappointing to people as it relates to women, all of those things, I think are legitimate things,” she said. “The things we’re called to foundationally stand for, I’m grateful that he’s taken a stand. But it’s not like it washes away those other things.”

Her words chimed with those of the dozens of Trump supporters I’ve interviewed, not one of whom approved of his racist comments. “I wish he would just shut up and run the country” is a sentiment just about every Trump voter I’ve spoken to has expressed. The other issue that always comes up is abortion, which most Evangelical Christians believe should be illegal and even view as murder. Many have explained their vote for Trump to me as an agonizing decision between backing a man who regularly attacks the downtrodden and supporting a rival candidate who, as they see it, advocates for killing unborn children.

But the members of The Refuge, black and white, have an unspoken pact to leave politics outside the doors of their houses of worship. By their lights, it’s simply too mundane and ungodly a topic to be allowed to interfere in the more urgent and sacred task at hand.

“I separate politics from church,” Tierra O’Garra agreed, reflecting a view that I heard from other black worshipers in Greensboro, too. “It’s a real church and state thing for me. I like to keep that separate.”

Pastor Derrick went further. “If I allow a president to override my relationship with a person, I think that lacks maturity,” he told me. “I’m not going to allow a president to keep me in a disunity with a person of a different color.”

The Refuge’s leaders and worshipers view the church merger as a phalanx in a cosmic battle between good and evil, between unity and racism, a battle they believe America must win—and is winning. This idea—that one can put politics aside for a greater good such as unity—was the hardest thing to accept for my New York liberal friends whom I told about this story. In their world, it is an article of faith that there’s no way to square supporting Trump’s presidency with active anti-racism. It’s a view that struggles to assimilate the contrary evidence from the example of The Refuge, whose black members see creating fellowship with the president’s white voters as central to combating racism.

“I know there are some things that [Trump] stands for and those that vote for him might still stand for,” O’Garra told me. “But honestly, for me, because it’s separate, I also believe in God, and I do believe there is going to be a change of heart and a change of mind regardless. A lot of things have changed since they voted for him, too, so a lot may have voter’s remorse at this point. At the end of the day, we’re still people of God.”

Pastor Jay credits the progress made to civil rights leaders like the Greensboro four, MLK, and Rosa Parks, all of whom he admires deeply. The day I called The Refuge to request an interview, Pastor Jay was out of the office because he’d taken the entire staff to the International Civil Rights Center and Museum in Greensboro.

“You walk through that place and go, How could our nation have ever done this?” He told me. “How could we ever treat anybody like this—just like you walk through Yad Vashem and go, How in the world, and how could the church sanction this?” (I had told Pastor Jay’s receptionist that I was an editor at a Jewish newspaper, which she had conveyed to Pastor Jay. He told me how much he respected the Jewish faith, and more than once, asked my opinion about the conflict in Israel. And he had been to Israel’s memorial to victims of the Holocaust, Yad Vashem.)

“I feel the same way about America as it relates to racism,” he went on. “How could we ever do that? How could we turn our heads away and say, it doesn’t exist, it doesn’t happen. So, yes, we’ve made progress, tremendous progress. But I feel we still have a long ways to go.”

*

The next morning, I paid a visit myself to the International Civil Rights Center and Museum. The Museum, which opened in 2010, is built around the original whites-only Woolworths lunch counter, where the Greensboro Four—Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, Ezell Blair Jr., and David Richmond—made their stand. The outside of the museum still bears the Woolworths sign, its red background with gold lettering a testament to our national stain.

To tour the museum, I joined two white couples and a multi-generational black family that was on a reunion weekend. We crowded into the first hall of the museum in front of a large glass case that displayed an American flag and the words “All Men Are Created Equal” floating above it. As we looked, the visual morphed into a series of historical signs that read “Whites Only,” “Colored Fountain,” and so forth.

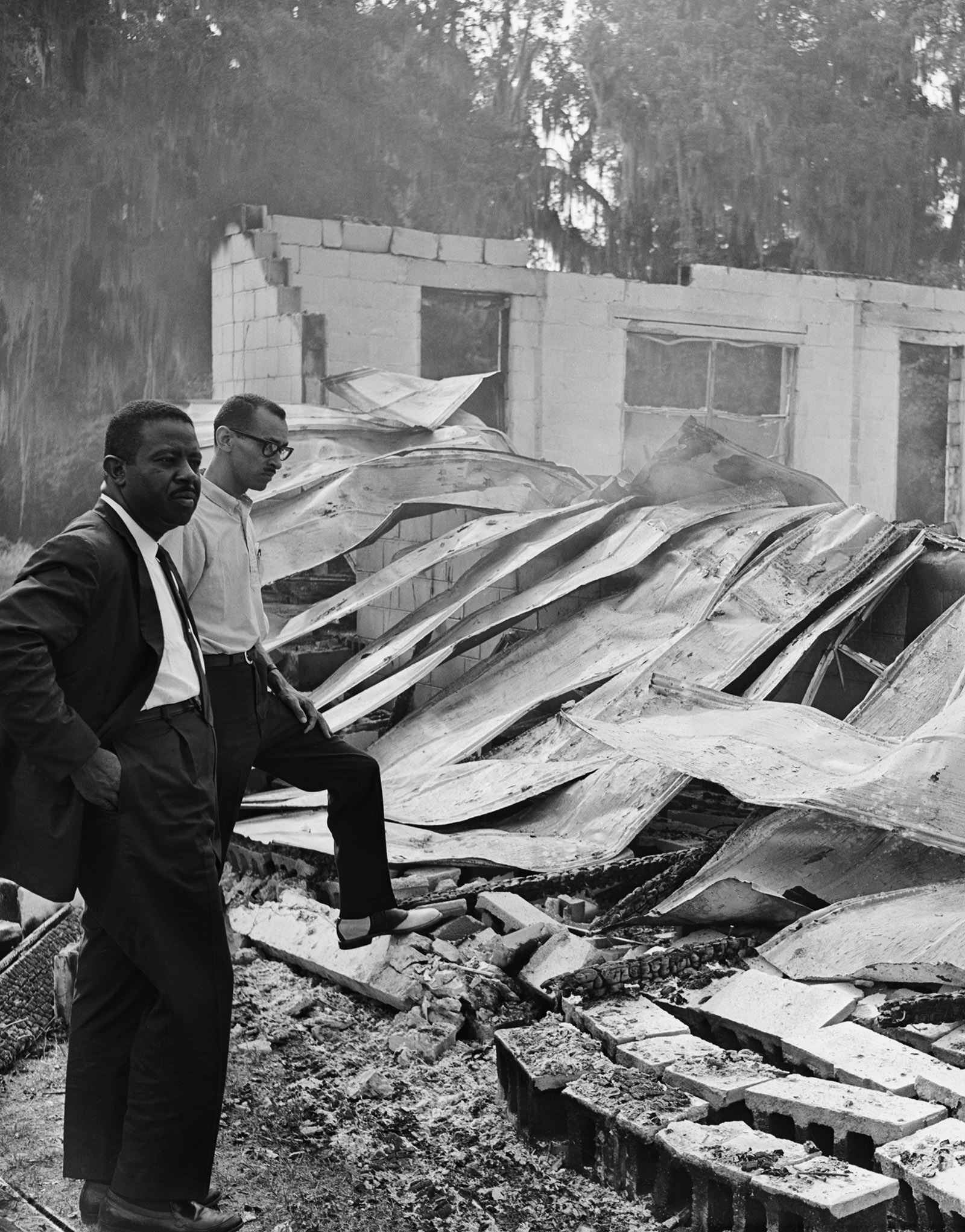

Our guided party walked through hall after hall dedicated to educating visitors about the Jim Crow laws, the dispossession of black rights and black property, the violence and lynching, the dehumanization of segregation, and the completely systematized cruelty—like the Coke machine that charged whites five cents a bottle and blacks ten cents a bottle, or the barriers on the bus to divide whites from blacks, which had clips on them so that the bus driver could move them farther and farther back as the bus got full, crowding the black riders more and more.

Most striking of all is the fact that this wasn’t such distant history. One entire wall is made up of mugshots of civil rights activists, and visitors to the museum, we learned, frequently find their picture posted there while visiting. Our guide was herself born in an all-black hospital.

Driving out of Greensboro, I felt wrung out. Pastor Jay was right: the museum was like Yad Vashem. But when I walk through Yad Vashem, I don’t have to feel guilt. I only have to feel anger at what was done to us. In the Greensboro museum, this sin was not someone else’s. As an American, it was mine.

This country’s sins against African Americans are grave indeed. I thought about something surprising Pastor Jay had told me, about how unworthy of God’s love he felt. He saw himself as so hopelessly fallen, so wretched, that only the grace of God, which allows Jesus’s sacrifice to cleanse us mortals, could make their relationship possible. He had teared up describing how much compassion on God’s part it took to grant this grace.

In Judaism, we don’t have the concept of grace. We aren’t born steeped in sin, but in a neutral state. You’re worthy of God’s love as long as you follow his commandments, and when you fail and sin, you can earn back his love with t’shuva, repentance.

Was there a form of repentance that could restore us, and make us worthy of love, worthy of pride as a nation? Or was the sin of our history too grave? Would only grace do? And if so, who could grant it?

*

The first time I saw Pastor Derrick, he was standing in the center of the darkened auditorium of The Refuge’s Greensboro campus. He was facing the stage, hands stretched to the heavens, and his face seemed to radiate light.

“We need your glory!” One of the four singers sang into a microphone from the stage, accompanied by three others in harmony, two electric guitars, two keyboards, and a drumset. “We need your glory! We need your glory!”

Pastor Derrick was wearing a black-and-white checked shirt, skinny jeans ripped at the knees, and white sneakers. He looked more like a grad student than a preacher. He was surrounded by about a hundred of his parishioners, many of whom also had their hands outstretched and their eyes closed, and like him, were swaying to the music.

Later in the service, he joined the singers on the stage, and while he preached, they continued to sing “Hallelujah!” in a low, escalating hum, as the drums kept up a steady beat. The energy in the room, the pure joy, felt as though it could power a small town. Pastor Derrick began to speak about the miracle of God’s love, how it saw past mistakes and failures. He invited a young white man to the stage to speak about the sin of abortion. Then he came back on stage, and in his low, gravelly voice began his sermon.

“Not only are we talking about abortion, we’re talking about race. Because we have a strong racial barrier in our country,” he said.

“All right,” a voice from the crowd affirmed.

“For some of you, for some of us standing in difficult positions in advancing the kingdom, and you’re facing attack, and you do not understand what God is doing, I need you—this message is not for everybody but for you—I need you to hold on in the seasons of your life, where you don’t understand: Why did I have to go through what I had to experience?” His voice rose.

“Why did the relationship have to end? Why do people have to walk away?” He began to cry out: “Why do people that I trust have to leave me? Why did my grandmother have to die? All of these things that challenge us, God! WHERE ARE YOU IN THE MIDST OF THIS?” Pastor Derrick beseeched. “I need you to hold on to your faith!”

I would learn that Pastor Derrick was speaking from first-hand experience. His mother abandoned him soon after he was born, leaving him to be raised by his grandmother and her abusive husband, who eventually kicked Pastor Derrick out at age thirteen. The boy went to live with his father, but the memories of the abuse lingered. He was afraid of his father’s voice. And his father’s wife suffered from bipolar disorder. He remembers sleeping in cars so as not to be home.

He started dating early, searching for the mother’s love that he never received. There were many failed relationships, more bad decisions, and a stillborn baby that broke his heart. He had a nervous breakdown at twenty, and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for ten days, during which time he was strapped down in a padded room.

Those were some of the darkest days of his life. He had been attending college, but after his breakdown, he left school and moved back home. He started working, and at his job, he met a soft-spoken, refined woman named Roshonda. For her part, she felt drawn to him and called to pray for him. Roshonda had two children from a previous marriage, and had been single for seven years. They became friends, best friends, and eventually, a few years later, they married.

Pastor Derrick was twenty-three then, and he and Roshonda have been married ever since. They had two children together, two boys, and fostered a girl whom they took in when her mother died. Family is deeply important to Pastor Derrick, especially providing an example in his community of a stable home. After the service, the whole family including the two little boys, sat around a table in Pastor Derrick’s office, and they all listened quietly as Pastor Derrick told me about the merger.

“Blacks and whites, right now? What I’m doing is not popular,” Pastor Derrick said. “So many people have asked me, ‘Could you not have merged with a black church? Did you have to merge with somebody white?’ This is the South.

“So it’s been challenging,” he conceded. “And with the current administration, with African Americans, it’s to the point where we’re past talking. ‘We believe this, they believe that.’ That’s it. So it’s kind of difficult. But we just have to navigate through it.”

I asked Pastor Derrick how he felt about the fact that many of the members of the white church he’d merged with probably voted for Trump. He laughed, long and low.

“I don’t talk politics,” he said. “I think that’s the only thing that’s kept me sane—that I refuse to talk politics with them at work. I know there are a lot of people that probably support the administration. And not everything is bad, you know? I think there are good things and bad things. But I try to just stay positive and build relationships with people.”

It was then he told me that he thought it lacked maturity to let a president get between him and people of a different race. “I don’t think everybody who voted for President Trump is a racist. But I do feel there’s a great misconception that racism is just hooded people walking around in KKK clothing,” he said.

“In the Fifties and Sixties, we had a lot of lynchings. But now we have a lot of mass incarceration—and that’s affecting us just as much,” he continued. “The issue, the struggle, is equality. African Americans don’t feel that we are valued. We want to be treated equally. For me, I just want to be treated equally.”

He didn’t shy away from the harsh realities of racism in America. He brought up police brutality, mass incarceration, redlining, and the economic gap between black and white communities as symptoms of systemic racism today, a persistent disease that not everyone can recognize, or acknowledge, or take responsibility for. Still, Pastor Derrick is hopeful.

“You gotta think, we are only forty-some odd years from segregation,” he told me. “In the 1960s, you couldn’t even sit in the same room as us, right? So yeah, I think if we make those same strides moving forward, what does forty years from today look like? I think it looks better.”

But it will take a conscious effort. “If a person doesn’t believe they have ever done anything for us, against us, how can we ever move the country forward?” he asked. “Take ownership of it. You can’t say you’ve moved on if the same stuff is happening today. That’s key for us.”

*

I also went to a service at the Kannapolis campus of The Refuge. Like the Greensboro campus, the room was dark and cavernous. The stage was lit up by flashing colored lights as if we were at a rock concert. There was a six-piece band on the stage, comprised of two electric guitars, an acoustic guitar, a bass guitar, drums, and a keyboard. Three people were singing, two women and a man, and while they sang, a black man was preaching from the floor in front of them. There were forty or fifty people when I arrived, whose numbers would rapidly swell to about 500 before I left. And there seemed to be about a dozen black families standing among the white ones, everyone swaying to the music, many with hands outstretched.

“Show us your glory! Show us your glory!” One of the singers sang. “Jesus, you change everything!”

Pastor Jay walked to the front of the room. But before he started preaching, he told the crowd he wanted to introduce a new friend.

“You guys know that God’s put something on this house as it relates to racial reconciliation,” he said. “And it’s interesting that we got a call just a couple of weeks ago from a journalist in New York City who had run across our story just doing some research on the Internet, and asked if she could come down and interview myself and Pastor Derrick,” he said. “Batya Ungar-Sargon—could you come on down here? This is Batya.”

Everyone in the room clapped as I made my way to the front of the auditorium.

“Can a couple of our pastors gather around Batya, and can you just join me as we pray for her today?” Pastor Jay asked. A group of pastors and worshipers gathered around me, of all races. Their hands reached out for me, and found me, and I felt tears gathering in my eyes. Against my will, they began to flow.

“Lord, we thank you that Batya is here, and that she’s able to attend The Refuge today, and thank you God that she ran across our story,” Pastor Jay prayed. “We don’t think that was an accident. We believe the providential hand of God led her to our story.

“God, you continue to breathe life on what we’ve done here at The Refuge,” Pastor Jay went on. “Father, we just pray over this work, that it will be used by you to bring racial healing and racial unity in our nation.”

I lost the battle with myself and wept openly. Pastor Teri, whose hand was on my arm, gently handed me a big wad of tissues. I wanted so desperately to believe what Pastor Jay believed, that a benevolent, divine, forgiving force was at work healing our nation, helping us right the wrongs and atone for the sins and reach beyond the current situation of denial and distrust, of black communities decimated by state sanctioned violence and theft. Could the proof that the battle was slowly being won be found here, where Pastor Jay and Pastor Derrick had joined forces to fight fear and hate?

Three years into the merger, The Refuge remains united. Pastor Jay’s congregation in Kannapolis now numbers around 4,000. And Pastor Derrick’s community has swelled to 250 families. Through their love of Christ and their love for each other, Pastor Jay and Pastor Derrick have guided their communities through any divisions that might threaten their unity.

Could theirs be a model for healing our nation? I asked Pastor Derrick what he thought a healed America would look like.

“Valuing each other. Loving each other. Appreciating each other’s backgrounds and differences,” he said. “It doesn’t mean we have to agree on everything. But it means that we have to embrace and accept and walk in love. That’s what a healed America looks like.”

But healing also requires taking ownership of the past and acknowledging the injustices that persist. “We have to call it what it is, and embrace it, and heal from it,” Pastor Derrick said. “But understand that sometimes, walking and healing, you embrace pain. It doesn’t mean that you’re not healing.”