On June 24, 2019, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum issued a formal statement that it “unequivocally rejects the efforts to create analogies between the Holocaust and other events, whether historical or contemporary.” The statement came in response to a video posted by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Democratic congresswoman from New York, in which she had referred to detention centers for migrants on the US southern border as “concentration camps.” If the historical allusion wasn’t already apparent, she added a phrase typically used in reference to the genocide of European Jewry: “Never Again.” Always a favorite target of right-wing politicians, Ocasio-Cortez drew a scolding retort from Liz Cheney, the Republican Congresswoman from Wyoming, who wrote on Twitter: “Please @AOC do us all a favor and spend just a few minutes learning some actual history. 6 million Jews were exterminated in the Holocaust. You demean their memory and disgrace yourself with comments like this.” In the ensuing social media storm, the statement by the Holocaust Memorial Museum against historical analogies gave the unfortunate appearance of partisanship, as though its directors meant to suggest that Cheney was right and Ocasio-Cortez was wrong.

Much of this might have been a tempest in the tweet-pot were it not for the fact that, on July 1, 2019, an international group of scholars published an open letter on The New York Review of Books website expressing their dismay at the Holocaust Memorial Museum’s statement and urging its director to issue a retraction. “The Museum’s decision to completely reject drawing any possible analogies to the Holocaust, or to the events leading up to it, is fundamentally ahistorical,” they wrote. “Scholars in the humanities and social sciences rely on careful and responsible analysis, contextualization, comparison, and argumentation to answer questions about the past and the present.” Signed by nearly 600 scholars, many working in fields related to Jewish studies, the letter was restrained but forthright. “The very core of Holocaust education,” it said, “is to alert the public to dangerous developments that facilitate human rights violations and pain and suffering.” The museum’s categorical dismissal of the legitimacy of analogies to other events was not only ahistorical, it also inhibited the public at large from considering the moral relevance of what had occurred in the past. Granting the possibility of historical analogies and “pointing to similarities across time and space,” they warned, “is essential for this task.”

I was neither an author of this letter nor an original signatory, but like many others, I later added my name, as I felt the issues it raised were of great importance. The debate involves an enormous tangle of philosophical and ethical questions that are not easily resolved: What does it mean when scholars entertain analogies between different events? How is it even possible to compare events that occurred in widely different circumstances? The signatories of the open letter to the USHMM were entirely right to say that analogical reasoning is indispensable to the human sciences. But it’s worth turning over the deeper, more philosophical question of how analogies guide us in social inquiry, and why they cannot be dismissed even when some comparisons may strike critics as politically motivated and illegitimate.

*

Joseph Priestly, the eighteenth-century chemist and theologian, once observed that “analogy is our best guide in all philosophical investigations; and all discoveries, which were not made by mere accident, have been made by the help of it.” While it seems improbable that all scientific inquiry must rely on analogy, analogical reasoning does play a central role in much empirical inquiry, in both the natural and the social sciences. (There’s an important difference between analogy and comparison but I’ll ignore that difference here.) The philosopher Paul Bartha has written that analogy is “fundamental to human thought and, arguably, to some non-human animals as well.” Indeed, chimpanzees that learn to associate a certain sound with a particular reward are making analogical inferences: if a sound at time X announces food, then a comparable sound at time Y should also announce food. This same logical structure recurs throughout the empirical sciences. Bartha, citing the philosopher of science Cameron Shelly, offers the example of analogical reasoning among archaeologists in the Peruvian Andes. Unusual markings that were found on old clay pots remained mysterious until researchers noticed that contemporary potters used similar marks to identify the ownership of vessels baked in a communal kiln: they inferred that the old markings had a similar purpose. Similar habits of analogical inference guide scientists in their speculations about features of the cosmos. Even if they cannot empirically verify that a remote corner of the universe exhibits a certain pattern of astronomical phenomena, analogy permits them to infer that the laws that obtain in our galaxy most likely obtain elsewhere, too.

The first thing to note about such analogical inferences is that they commit us to a basic view that the two distinct phenomena in question belong to the same world. Famously, the first line of British novelist L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between declared that “the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.” And historians, along with anthropologists, are often eager to say that humanity exhibits an astonishing variety of habits and moral codes, and that the standards that apply in one case may not apply in another. Historians are especially keen to argue that historical inquiry alerts us to difference: things that we might have assumed were eternal features of the human condition are in fact specific to their time and may have changed, sometimes in drastic ways, over the course of history.

Advertisement

But claims about difference should not be confused with claims about incommensurability. When I say that A is like B, I presume that there is a common standard (or language or culture) by which I could legitimately raise the matter of similarities or differences at all, since otherwise the task of comparison could not even get off the ground. Just because A is dissimilar to B in certain respects does not imply that there can be no common measure by which they might be compared. When applied to the human sciences, the incommensurability thesis—the claim that discrete phenomena are unique in themselves and cannot be compared to anything else—has some very odd consequences, since it leaves us with a picture of human society as shattered into discrete spheres of time or space, as if A belonged to one world and B to another.

Notwithstanding its manifold difficulties, this picture still enjoys some popularity in the human sciences. It has gained a special authority in anthropology, a discipline that has been seized by the anxiety that it had imposed patronizing or distorting standards on other cultures and had made false assumptions about what a given cultural practice meant. Tied to this methodological anxiety was the more explicitly political concern that anthropology had not rid itself of its imperialist origins. The incommensurability thesis offers a welcome release from this problem as it enables the anthropologist to reject all claims of Western supremacy.

The incommensurability thesis also enjoyed a particular prestige among scholars in the Anglophone world, especially in the 1980s and 1990s when French post-structuralist ideas were ascendant in the human sciences and in some precincts of philosophy. Michel Foucault believed that notions of rupture or discontinuity would eventually displace conventional themes of linear progress. Following philosophers of science such as Gaston Bachelard and Georges Canguilhelm, Foucault argued that one could properly understand modern science only if one abandoned the commitment to “great continuities” in thought or culture and turned instead to “interruptions” or “thresholds” that “suspend the continuous accumulation of knowledge.” He admitted that the notion of discontinuity was riven by paradox, since it “enables the historian to individualize different domains but can only be established by comparing those domains.” But he was tempted to defend a theory of “epistemes” (or frameworks of knowledge) as radically distinct.

When one episteme yields to another, he argued, it is as though the fundamental schema by which the world is intelligible suddenly gives way, and the resulting shift is so abrupt that we must give up nearly any notions of continuity between them. This controversial idea bears a noteworthy resemblance to Thomas Kuhn’s theory of scientific revolutions, since Kuhn, like Foucault, saw the history of science as a jagged rather than linear path, marked by abrupt shifts in paradigms. Kuhn went so far as to say that in the wake of such a tectonic shift the scientist lives “in a different world.”

Whether Foucault or Kuhn held such views in earnest is a matter of some dispute. Foucault eventually abandoned his “archaeological” method and adopted a method of genealogy that restored a sense of continuity across long stretches of time, charting, for instance, a path from the Christian confessional to modern psychoanalysis. What Kuhn actually meant with his talk of different worlds is still anyone’s guess, but the philosopher of science Ian Hacking suggests that Kuhn was at heart a rationalist who (unlike radicals like Paul Feyerabend) did not really mean to endorse the full-blown theory of incommensurability. More recently, philosophers and historians enchanted by post-structuralism will still declare that the past is discontinuous with the present, that its very reality is not something we can affirm, and that insisting on things being one way or another is a sign of ontological naïveté. To such historians, it may suffice to say that at least some facts are certain: the dead are truly dead.

Advertisement

Though scholars may continue to disagree about who most deserves the credit or the blame for popularizing the idea of historical incommensurability, at least one thing seems certain: if this idea is right, then analogical reasoning in history becomes an impossibility. If I sincerely believe that a given event in the past belongs not just to a foreign country but to a world so different from my own as to break all ties of communication between them, then I have no license to speak about the past at all. If I am bound by the rules of my own time, then the past and all its events become in effect unknowable. A past that is utterly different is more than merely past; it has no claim on my knowledge and it might as well blink out of existence altogether. This is more than merely a matter of logic; it has political consequences. If every crime is unique and the moral imagination is forbidden from comparison, then the injunction “Never Again” itself loses its meaning, since nothing can ever happen “again.”

Among historians, however, the rush to say that the past is a foreign country typically has a more prosaic meaning. It is often just an extravagant way of warning against the bias of “presentism,” namely, the belief that current conventions obtained in the past precisely as they do today. Needless to say, this warning falls far short of the incommensurability thesis: saying that a given event was in some specific way different from a present event is no reason to say they cannot be compared at all. Unfortunately, historians—especially in the Anglophone world—often receive little training in the philosophy of the social sciences, and they tend to muddle this point. They conflate difference with incommensurability, making different countries into different worlds.

But if comparison is clearly legitimate, then why the worry about historical analogy? Part of the answer is that historians, by methodological habit, are inclined to see all events as unique, rather than seeing them, as a political scientist might, as a basis for model-building or generalization. The nineteenth-century German philosopher of the social sciences Wilhelm Windelband once argued that natural scientists typically strive for “nomothetic,” or rule-governed, explanation, while historians and other scholars of the human world are more invested in “idiographic” understanding—that is, they wish to know something in all its particularity. This is why historians more often than not will specialize in discrete epochs and individual countries, and why they tend to resist drawing from history any grandiose lessons regarding constants of human nature. Still, nothing about this idiographic method actually prevents the historian from comparing one event to another.

*

When it comes to the horrors of the Third Reich, however, trusted habits of historical understanding are often cast aside. Especially in Western Europe and North America, the genocide of European Jewry has taken on the paradoxical status of a historical event beyond history. Although most historians would, of course, insist that the genocide is a human event that can be known just as other human events are, in the popular imagination the idea has taken hold that the Holocaust represents the non plus ultra of human depravity. Its elevation into a timeless signifier of absolute evil has had the effect of making it not only incomparable but, in a more troubling sense, unknowable.

For those of us whose own family members were killed in the death camps, the temptation can be overwhelming to say that this crime was unique and that no analogies could possibly be valid. Especially among the children and grandchildren of the victims, this conception of the Holocaust seems to have hardened into a fixture of contemporary identity. A taboo now envelopes even its nomenclature. No other atrocity in modern times has gained the singularity of a proper name, with such biblical resonance and an entire field of academic study to ensure that its horrors are not forgotten. It has become our secular proxy for evil, an absolute in an age that has left all other absolutes behind. But those who would characterize the Holocaust as “evil” forget that this term belongs to the lexicon of religion, not history. Once the Holocaust is elevated beyond time as a quasi-eternal standard, all comparison must appear as sacrilege.

Confronted with such moral difficulties, it can hardly surprise us that some public intellectuals and politicians have adopted the posture of gatekeepers against comparison. But yielding to the idea of the Holocaust’s incomparability leads us into a thicket of moral perplexities. It is sometimes said that the Holocaust must remain beyond comparison because the traumas that were visited upon its victims cannot be compared to other traumas without somehow diminishing the particular horror of the Holocaust. But this argument is based on a category mistake. Every trauma is of course unique, and the suffering of each individual has a singularity that cries out against comparison. Yet the uniqueness of individual suffering is not diminished when the historian begins the grim task of understanding.

There is, after all, at least one common element in every trauma: it belongs to the common record of human events. Hannah Arendt’s description of Nazism’s evil as “banal” was not meant to diminish its horror but to magnify it, by reminding us that its perpetrators were not monsters but ordinary men. She feared that, in the public mind, the sheer magnitude of the Nazis’ crime would remain so opaque that it would be depoliticized and lifted free of political history, as if it had not been perpetrated by human beings at all.

But all human atrocities are human acts, and as such all are candidates for comparison. The twentieth century alone has given us instances enough of mass-murder to occupy historians of comparative genocide for many years to come. Between 1904 and 1908, the German Empire murdered an estimated 75,000 Herero and Nama people in territories along the western coast of South Africa—an event that scholars typically call the first genocide of the twentieth century. The Armenian genocide, between 1915 and 1923, took an estimated 700,000 to 1.5 million lives (the exact figure is still a matter of dispute). The Rwandan genocide in 1994 involved the mass slaughter of Tutsis, Twa, and Hutus—the number of deaths has been calculated at between 500,000 and one million. To disallow comparisons of these atrocities with the Holocaust risks the implication that some human lives are less precious than others, as if the murder of mass populations in the European sphere should arouse greater outrage than the murder of mass populations in Armenia or Rwanda.

But if all atrocities are comparable, then why did the Holocaust Memorial Museum issue such a categorical statement against the possibilities of comparison? My surmise is that the statement is not logical but political: its officials harbor the fear that the Holocaust will become little more than a polemical weapon in ideological contests between left and right. In a short paper posted on the USHMM website in 2018, “Why Holocaust Analogies are Dangerous,” the museum’s resident historian Edna Friedberg warned of politicians and social media commentators who “casually use Holocaust terminology to bash anyone or any policy with which they disagree.” She condemned “sloppy analogizing,” and Holocaust analogies that she called “grossly simplified” or “careless.” Such analogies are dangerous, she explained, because “[t]he questions raised by the Holocaust transcend all divides.”

But this just prompts the question of whether there might be legitimate analogies that are not sloppy or careless. Friedberg does not entertain this question, but it merits consideration. Like common law, the moral imagination works by precedent and example. We are all equipped with an inherited archive of historical events that serves as the background for everything that occurs. Especially when we are confronted with new events that test the limits of moral comprehension, we call upon what is most familiar in historical memory to regain our sense of moral orientation. We require this archive not only for political judgment, but as the necessary horizon for human experience.

Even the term “concentration camp” (not to be confused with “death camp”) has historical origins well before the Nazi era, as Andrea Pitzer laid out in her essay for the NYR Daily. Although, in the popular imagination, we may associate the term “concentration camp” mostly with the forced internment of ethnic, national, and political enemies during the Third Reich, the term was already in use in South Africa from around 1900. Such examples remind us that human beings are thoroughly historical; we inherit our nomenclature from the past, and even our highest moral standards are carved from the accumulating bedrock of past collective experience. To consider any event as being literally without comparison would violate our sense of history as a continuum in which human conduct flows in recognizable ways. Not all comparison is careless; as a form of moral reasoning, it is indeed indispensable.

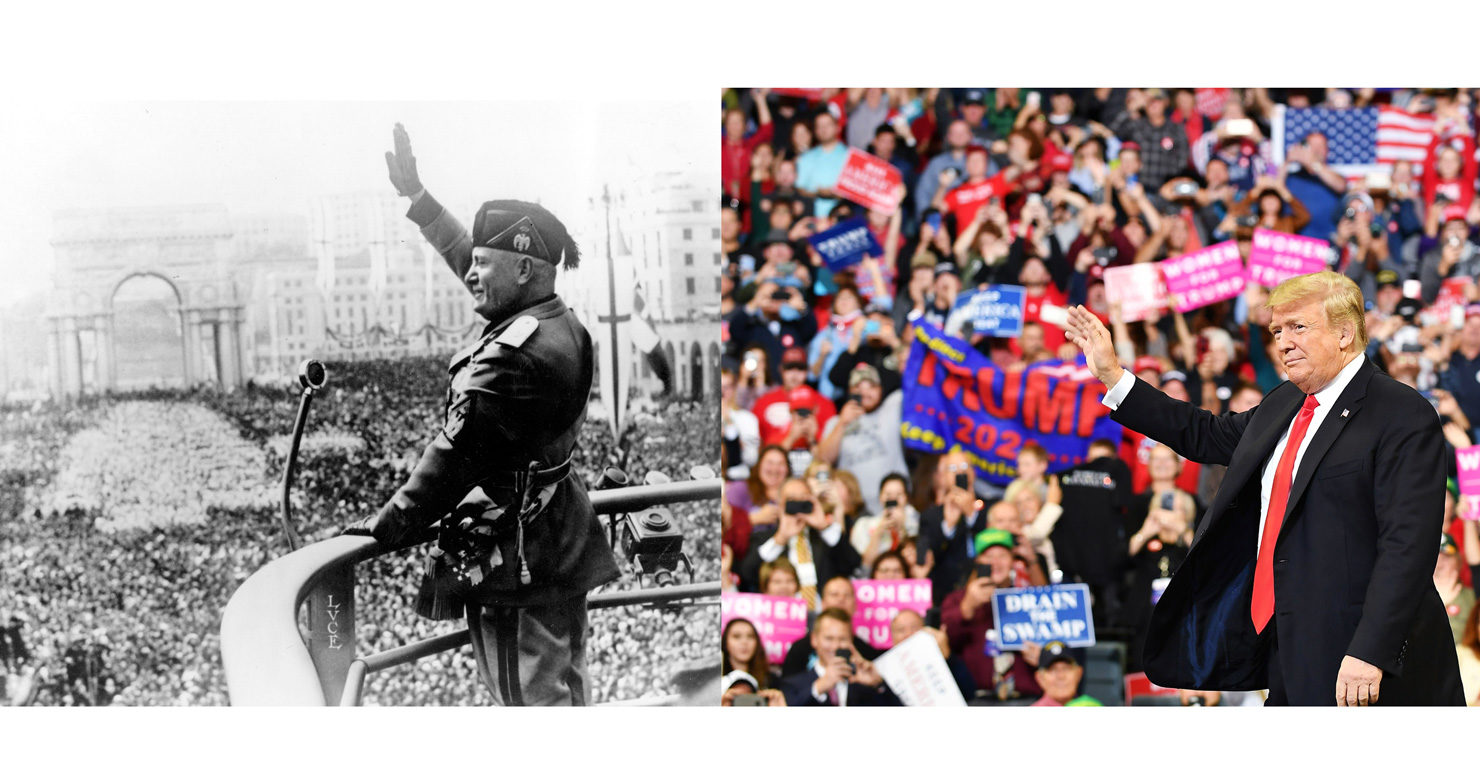

Looming behind today’s debates over the treatment of migrants in US detention centers and its historical antecedents is a larger question: Is the present administration descending into fascism? The question is hardly impermissible. Even if we regard Trump himself as a laughably unserious person whose own ideological convictions lack depth or consistency, the enthusiasm he has inspired among white nationalists would suggest that we take the comparison seriously.

Fascism, after all, is not only a historical term; it describes a modern style of authoritarian rule that seeks to mobilize the masses by appealing to nationalism, xenophobia, and populist resentment. Its trademark is the use of democratic procedure even as it seeks to destroy the substantive values of democracy from within. It disdains the free press and seeks to undermine its credibility in the public sphere. During World War I, German nationalists attacked the Lügenpresse (or “lying press”), a term that was later revived by the Nazis. The US president’s endless assault on what he calls “fake news” recapitulates this slur, and in his use of Twitter, he has shown great skill in circumventing the news media by speaking directly to his political base.

When we speak of fascism, the term can name both a historically distinctive ideology and a general style. Skeptics like Jan-Werner Müller reject contemporary analogies to twentieth-century fascism as mistaken in part because new authoritarian-populist regimes—such as Orbán’s Hungary, Erdoğan’s Turkey, Modi’s India, or Trump’s America—are aware that the term bears an intolerable stigma: today’s anti-democrats, Müller writes, “have learned from history” that “they cannot be seen to be carrying out mass human rights violations.” But this argument doesn’t refute the analogy; it confirms it. The new regimes can find ways to adopt the strategies of the past even as they publicly disavow any resemblance.

To be sure, no historical comparison is perfect. The differences between Trumpism and fascism are legion: the GOP has no paramilitary wing, and its party loyalists have not managed to capture the media or purge the political opposition. Most important of all, the White House has so far failed to promulgate a consistent ideology. But we hardly need to “equate,” as Müller puts it, contemporary right-wing populism with fascism to discern their similarities. The analogy permits a more expansive appeal to the political past. The fascism in Trumpism is largely aspirational, but the aspirations are real. This is one of the lessons of Jason Stanley’s recent book How Fascism Works, in which fascism assumes a very broad (if rather impressionistic) meaning, alerting us to commonalities across time and space that we might otherwise have missed.

The emigré philosopher Ernst Cassirer identified fascism’s method as the modern use of political “myths.” It imagines the masses not as a pluralistic citizenry but as a primal horde whose power can be awakened by playing upon atavistic feelings of hatred and belonging. Its chosen leader must exhibit strength: his refusal to compromise and readiness to attack are seen as signs of tough-mindedness, while any concern for constitutionality or the rule of law are disdained as signs of weakness. The most powerful myth, however, is that of the embattled collective. Critics are branded as traitors, while those who do not fit the criteria for inclusion are vilified as outsiders, terrorists, and criminals. The pugnacious slogan “America First,” brought to prominence by Woodrow Wilson and then by Charles Lindbergh during World War I, and now revived by Trump, functions as an emotional code, tightening the bonds of tribal solidarity while setting sharp limits on empathy for others.

“The most telling symptom of fascist politics,” writes Stanley, “is division. It aims to separate a population into an ‘us’ and a ‘them.’” A skeptic might say that this definition tells us nothing terribly special about fascism since the strategy of dividing the world into enemies and friends is a commonplace of politics everywhere. But this may be the most sobering lesson: fascism may be less a distinctive mode of political organization than the reductio ad malum, the dark undertow of modern society carried to an extreme. This was Cassirer’s view: fascism, he warned, was a latent temptation in democracy, a mythic form that could reawaken in times of crisis.

Our political nomenclature is always adaptive, attaching itself to new events as history unfolds. Consider, for instance, the term “racism.” When we speak of different institutions or practices as racist, we understand that this term maps onto reality in different ways: the institutions of American slavery and Jim Crow differ in a great many respects from the institutionalized racism of our own day. But historians of African-American history know very well that making use of a common terminology can alert us not only to differences but also to continuities. The manifold techniques of systemic racism—mass incarceration, discriminatory impoverishment, disenfranchisement through gerrymandering, and other modes of subordination, both subtle and overt—cannot be understood if we fasten only on the particular and somehow imagine that the past was a “different country.”

In the popular imagination, the belief persists that history involves little more than reconstruction, a retelling of the past “as it actually was.” But historical understanding involves far more than mere empiricism; it demands a readiness to draw back from the facts to reflect on their significance and their interconnection. For this task, analogy does crucial work. By knitting together the present with the past, the analogy points in both directions and transforms not only our understanding of the present but also of the past. Contemporary analogies to fascism can also change how we think about fascism itself, stripping it of its unworldly singularity and restoring it to our common history.

But this is not a liability of historical analogy, it is its greatest strength. Our interpretations are always in flux, and the question of whether a given analogy is suitable can only be answered by making the analogy to see if it casts any light, however partial it may be. All historical analogies are interpretative acts, but interpretation is just what historians do. Those who say that we must forgo analogies and remain fixed on the facts alone are not defending history; they are condemning it to helpless silence.

Meanwhile, some of my colleagues on the left remain skeptical about the fascism analogy because they feel it serves an apologetic purpose: by fixing our attention on the crimes of the current moment, we are blinded to longer-term patterns of violence and injustice in American history. On this view, cries of alarm about the rise of fascism in the US are implicitly calls to defend the status quo, since the real emergency is nothing new. But this argument is specious. Those who reject the analogy from the left have merely inverted the idea of American exceptionalism, a convenient trick that relieves them of the need for more differentiated judgment. After all, the fact that things have always been bad does not mean they cannot get worse. Ultimately, this skepticism is a game of privilege: those who would burn the whole house are not the ones who will feel the flames.

Among all the terms that are available to us for historical comparison today it is hard to see why “fascism” alone should be stamped as impermissible. No differently than other terms, fascism now belongs to our common archive of political memory. Exceeding its own epoch, it stands as a common name for a style of institutionalized cruelty and authoritarian rule that recurs with remarkable frequency, albeit in different guises. In the United States, it would no doubt take a different form. As the historian of European fascism Robert Paxton has observed, “the language and symbols of an authentic American fascism would ultimately have little to do with the original European models.” In an American fascism, he writes, one would see not swastikas but “Christian crosses” and “Stars and Stripes.”

The true signs of fascism’s resurgence, however, would not be merely the symbols it deploys in its propaganda but its treatment of those who are most vulnerable. This is why the spectacle of migrants in cages should alarm us all, and why we cannot take comfort in the thought that things are not as bad as they once were. The phrase “Never Again” can be used in a restrictive sense as a summons to the Jewish people alone that it should never permit another Holocaust to occur. But if the phrase contains a broader warning, it must apply across time and space to other people as well. By forbidding all comparison, this more expansive meaning is vitiated. The moral imperative that such an atrocity should never again be visited upon any people already implies the possibility of a reprisal—with all of its terrifying consequences.