Lockport, New York—The great debate over voting by mail has begun. President Trump has blasted it as an invitation to widespread fraud. He tweeted in June, “IT WILL BE THE SCANDAL OF OUR TIMES!” and has warned that Democrats plan to distribute ballots to undocumented immigrants, and that foreign governments will flood our mailboxes with false ballots. On the Democratic side, Senator Amy Klobuchar, taking stock of a potential new spike of Covid-19 infections just in time for November’s presidential vote, has declared: “In a democracy, no one should be forced to choose between health and the right to vote.”

April’s Wisconsin primary already offered a chilling look at what happens when going to the polls runs into a pandemic. More than seven thousand poll workers refused to work because they feared getting sick, leaving thousands of mask-clad voters standing in line for hours. On the other hand, absentee balloting leapt from 140,000 voters in 2016 to more than a million in this election—but not without glitches that left almost ten thousand voters without the ballots they had legally requested.

This November’s presidential election will certainly be the most heated and consequential in a generation. What we cannot afford is for that election also to become a democratic farce amid the ravages of a pandemic. In the rising national debate over voting by mail, somewhere between the claims of fraud on one side and of panacea on the other, lies a tricky middle ground called reality: What would a nationwide election-by-mail really look like? What bumps in the road should we prepare for?

Some voters in some parts of the US are already getting a sense of the challenges ahead. Here in the small, conservative city of Lockport, in the far northwestern corner of New York, we had this past June a test run in miniature of what an all-vote-by-mail election looks like when the city school district’s elections for the Board of Education became an experiment in an election run entirely by post.

These annual elections generally exhibit two consistent qualities: they are wickedly dull and no one shows up. In 2019, a field of four candidates running for four seats drew 856 voters from the 21,000 people registered in the school district to vote. In 2018, a hot contest with four candidates vying for three seats scored a little higher, with slightly more than 1,100 voters, a turnout just above 5 percent. This is not exactly democratic participation at its finest. Student government elections at our high school elicit more votes.

In 2020, all that changed—for three reasons: a local controversy over deploying facial recognition surveillance in the schools; anger in Lockport’s black community over the district’s refusal to hold onto a beloved African-American middle-school counselor; and, most of all, a May 1 executive order from New York Governor Andrew Cuomo mandating that all of the state’s school board elections be conducted exclusively by mail-in voting. The result was an election in which turnout leapt an astounding fivefold. So many people voted that it took election workers three days to count all the ballots.

*

A visit to a meeting of the Lockport Board of Education is like a journey in a time machine back to the 1950s. The sessions begin with a heartfelt pledge of allegiance to the flag, for which all stand and place their right hand over their heart. The board president, who has been a member for six years longer than it takes for the district to turn a kindergartner into a graduating senior, wields a heavy gavel. Public participation is so unusual that if there is any, it often makes news in the local paper (for which I write a weekly column). On the winter night in 2018 when I showed up to speak about that controversial surveillance system, a member of the board read aloud a statement explaining that, while the district was under no legal obligation to hear what I had to say, it was granting me a hundred and eighty seconds as an act of courtesy. (Nearly two years later, when I heard the school board, all of whose nine members were white, read this same statement aloud to a packed crowd of frustrated black families, the arrogance of it was especially unnerving.)

The school district wanted to spend $2.7 million to make ours the first in the nation to deploy facial recognition surveillance in its school hallways, a huge fortune in a district with fewer than 5,000 students. In my allotted three minutes, I pointed out that the supposedly independent security expert who had pitched the project was actually a partner in the company selling it. I also noted the dangers of turning our community’s children into lab rats for a system akin to what authoritarian regimes in Russia and China use to track dissidents. The school board approved the contract anyway.

Advertisement

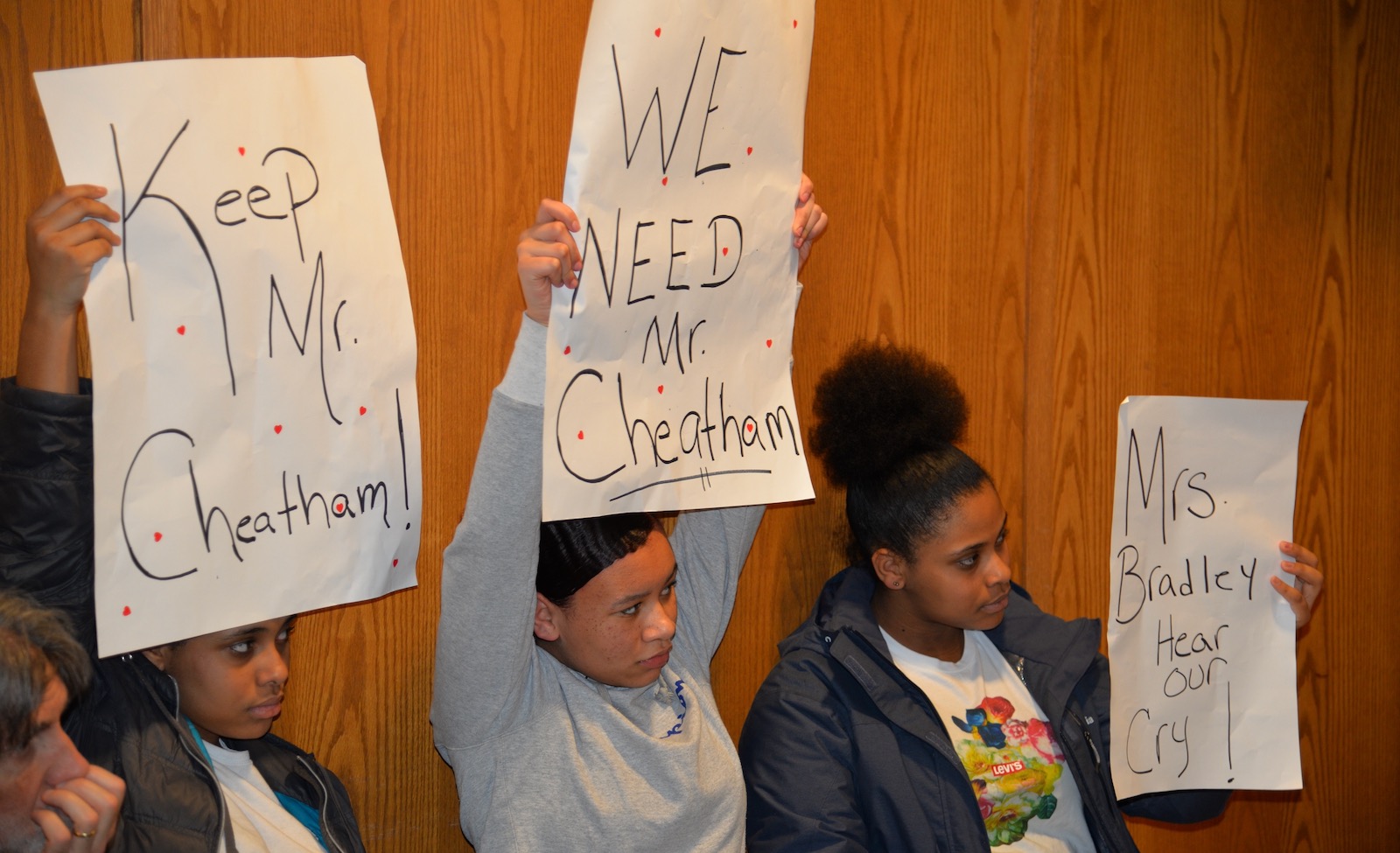

The other major recent controversy in our district involved a retired General Motors worker named Ron Cheatham. Since 2007, Cheatham, who is black, has worked in our schools as a peer mediator (as the position is known). A gentle soul beloved by the students, teachers, and parents alike, he specializes in counseling children at that difficult middle-school age of twelve and thirteen. “This man is such an encouragement to these young men and women who are going through different things during their middle school years,” one mother told a jammed school board meeting this past January. “The one person who seems to always be there is Mr. Ron Cheatham.” When he reached the age of sixty-two, he asked the district if he could switch to half-time working to avoid losing his Social Security payments as a retiree. The district denied his request.

When you look at these two local issues together, you can see something about our current national battle over policing in small form. Lockport is not a school district with a particular violence problem, yet school officials happily spent $2.7 million on high-tech surveillance cameras. But those same officials were unwilling to spend less than $25,000 on a counselor who deals with the real problems and conflicts that students experience day to day. This connection was not lost on Lockport’s black community, in particular—as Ron Cheatham’s daughter, Kiki pointed out to the board, employing her father “cost less than that facial recognition, I can tell you that.”

*

With these two issues, the cameras and the counselor, simmering in the community, New York headed into its annual school board election season. Under normal conditions, the mechanics of school board elections in Lockport look like this: interested candidates need to collect and submit a minimum of a hundred and fifty signatures from registered voters to get on the ballot in late May; the local PTA hosts a poorly attended candidates’ forum in the high school auditorium; then, finally, on election day, roughly one out of twenty eligible voters, mostly employees of the district and their families, filter through the sparse voting booths at the district office, followed by a quick counting of the ballots and announcement of the results. Like so many other things in 2020, Covid-19 changed all that, too.

Under the executive order issued by Governor Cuomo, the requirement to submit petitions was suspended—gathering voter signatures and social distancing would not go together well. Instead, a candidate just needed to submit a form. More important, the voting itself was ordered to be carried out entirely by mail, with June 9 set as the deadline for ballots to be received and counted. That was the plan.

In Lockport, the twin controversies led to a surge of interest in the election: a record eleven candidates filed to run for four seats. They included three incumbent members seeking reelection and seven reform candidates running on two different slates. One slate, comprising entirely African-American candidates, was led by Renee Cheatham, the charismatic wife of Ron Cheatham, who had become a powerful critic of the current board. The second slate, which had both black and white candidates, was also critical of the board, running under a “Kids First” banner. This unusual election was administered by the school district’s long-time business manager, Deborah Coder, the same official who had overseen the facial recognition cameras project. It did not go well.

On May 23, the same day that absentee ballots were supposed to have arrived in people’s mailboxes, what arrived instead was a small yellow post card from the district that incorrectly advised nine out of ten eligible voters that they couldn’t legally vote in the school election. In addition to outlining the normal legal requirements—being eighteen years old, a US citizen, a resident of the school district, and registered to vote—the district notice added on one more legal requirement: you had to have voted in at least one other school election in the past four years. Because voter turnout in these elections never even cracks the 10 percent mark, this would have excluded more than 90 percent of the voters. The result was widespread confusion.

Fortunately, the editor of the Lockport Union-Sun and Journal, Joyce Miles, spotted the mistake and called it out on the front page. At first, the district insisted that the requirement was real, but two days later officials relented and declared that it had been a “proofreading error.” In the end, the district had to spend another $8,600 to send out a correction postcard, but for many, the episode left a whiff of voter suppression hanging over an election in which five black candidates were trying to crack open an all-white board.

Advertisement

The next election setback had to do with the ballots themselves. Under Cuomo’s plan, absentee ballots were supposed to arrive more than two weeks before they were due, giving voters ample time to get informed, mark their ballots, and mail them back. In Lockport, as elsewhere in the state, the promised date came and went—and no ballots arrived. It eventually emerged that the company the school district had hired to send out the ballots had run out of envelopes. As a result, most people received their ballots only about three days before they had to be mailed. Logistical delays like this hit so many districts across the state that at the last minute, Cuomo extended the voting period by a week, allowing voters the time they needed to receive their ballots and mail them in.

*

One of my favorite vignettes from the school election this year involved the giant bright yellow wooden ballot box that the district set up at the rear of its office. Voters had the option of either putting their ballots in the mail or hand-delivering them into this box (as I did, which means that technically I voted by bicycle). School district officials apparently did not consider that the massive box, wrapped in the heavy chains and padlocks, made it sufficiently theft- or tamper-proof, so they hired retired and off-duty Lockport police officers to stand guard over it for the twelve hours a day it stood outside. One late afternoon, as I rode by, an officer was snoring in a lawn chair set up next to the ballot box. Democracy was safe.

Covid-19 also stripped local electioneering of its usual rituals. Knocking on doors was out. So was the candidates’ forum at the high school. Instead, like all other things in 2020, campaigning went online. Two local community Facebook pages became forums where candidates posted their biographies and pledges, and where they held virtual town halls for anyone willing to tune in.

All of this, however, also took place against a national backdrop that went beyond just the pandemic to the protests spreading across the country against police violence that’s killed black people. Here in Lockport, that is not something theoretical or far away. It is local and deadly real.

A year ago, in June 2019, Troy Hodge, an African-American father of three, was killed in a violent encounter with police during which he was handcuffed and tasered by officers from the Lockport police department and deputies from the Niagara County Sheriff’s Office. Reportedly, Hodge was having a breakdown, possibly exacerbated by drugs,and his mother called the police for help. That help left him dead.

In the days after his death, there were protests and vigils and a city council meeting was taken over by angry members of the community demanding answers. The investigation was handed over to the New York attorney general; a year later, the Hodge family is still waiting for a response.

Just as people were casting their ballots in the school district election, people here, as in so many other places, were taking to the streets in protest, and the connection between the voting and the protests was becoming more clear. At one large City Hall rally, a council-member declared to great cheers that coming out into the streets was important but that people also had to vote—and that included voting for the black candidates seeking a greater voice in the governance of Lockport’s schools, in which black students get suspended at twice the rate of everyone else. And it’s not only about the schools: in a city that is almost 8 percent black, not a single member of the city council, nor a single police officer or firefighter, is black.

A week before the ballots were to be counted, there was evidence that something extraordinary was happening. The school district announced that it had already received more than 4,100 returned ballots—nearly four times as many as in any recent schools vote (and there were still more ballots to come in). Despite the earlier missteps, it seemed as though a tiny school district in western New York might end up demonstrating what could happen if you made it easy for people to vote and gave them something meaningful to vote for. Even supporters of the incumbents started to concede that the old guard might be swept away by an expanded and altered electorate. By election day, more than 5,300 people had voted, a number five times the normal.

As the count continued through its second day and the announcement came that it would have to spill into a third, a large and somber crowd gathered outside the home of Fatima Hodge, Troy’s mother, at the spot where her son was killed in his struggle with police exactly a year earlier. It was the first time his mother had spoken publicly about it and she delivered a long and powerful call to action. “There is a time and a place and a season for a change,” she said. “I’m telling you this is the time. Nothing comes easy, but you got a choice to make that change.”

The next afternoon, the results of Lockport’s school elections were announced live via a video feed of a special board meeting called for that purpose. Renee Cheatham had finished in a commanding first place, garnering more votes than any candidate in memory. Behind her, though, the three other winners included not a single one of the other challengers, but instead the three incumbents, a result that may have been as much of a surprise to them as to everyone else.

In the end, the 2020 Lockport election results were not especially different from most elections for the board. The candidates supported by the Lockport Education Association (the teachers’ union) won, and those it didn’t lost. Cheatham herself had won the union’s endorsement, but she was the only non-incumbent to do so. One larger lesson to be taken from this is that in a local vote like this one, even with the backdrop of political passions and a fivefold increase in turnout, the results were still dominated by a small but well-organized interest group with a strong and direct stake in the outcome and an operation capable of sending out mailers and making phone calls. The union has one priority—protecting its interests in the negotiations over its contract—and in Lockport staying friendly with board incumbents is how that’s done.

*

What this will all mean for Lockport schools is still unfolding. The city’s black community is politically active here in a new way, and its demand that the needs of black students be addressed is not going away, especially with a formidable advocate now on the inside. The controversial surveillance system, which spent the semester recognizing no faces at all in the empty school hallways, is probably doomed for legal reasons. The week after the schools election, the New York Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against the New York Department of Education calling on it to enforce state student privacy protections and unplug the system. The two parent plaintiffs in the case are Renee Cheatham and myself.

But more importantly, what does this story about a small school district election offer up as lessons about voting by mail this November on a far bigger scale?

The first lesson is that voting-by-mail in Lockport did achieve important things: no one was prevented from voting out of fear for their health, and neither voters nor poll workers had to put themselves at risk by braving long lines and crowded polling stations. That is a not-insignificant achievement, especially if there is a second wave of Covid-19 in the fall. It also proved that making voting easier can have a huge impact on voter turnout. Lockport’s turnout leap of 500 percent was no accident. Granted, when your normal elections only draw one voter out of twenty your room for growth is pretty huge. Considering, however, that the Democratic Party dreams of a turnout increase of around 12 percent, it is easy to see how voting by mail could play a big part in getting there.

The second lesson is that the mechanics of mail-in voting matter, a lot. Balloting by mail adds a whole set of steps that aren’t required when voters just show up at a polling place and deposit their ballots into a slot or a scanner. Mail-in ballots need to be produced, they need to be correct, they need to be sent out on time, they need to arrive reliably, with enough return envelopes, and people need clear instructions on how to mail them back (including such new complications as signing the envelope, a standard absentee ballot security measure). Such nuts-and-bolts issues are not of a type likely to stir the passions of activists, but getting them right is essential. This is true not only to assure that everyone has the right to vote but to assure broad public confidence in that voting. With an army of conspiracy theorists, including the one in the Oval Office, eager to call fraud in the event that President Trump loses in November, we can’t afford to make the kind of needless mistakes that plagued our little election here along the banks of the Erie Canal.

Finally, Democratic partisans need to be very careful about assuming that increasing turnout in November will automatically damage Trump’s reelection prospects. To be sure, that is what he fears from voting-by-mail—as he said, “levels of voting that, if you ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.” The political science on this, however, is more complex.

It is true that, overall, the nation’s 100 million eligible non-voters tend to be younger and are more likely to be people of color than those who do vote, which suggests the kinds of voters who would break Democratic if they did cast ballots. But, as we learned painfully in 2016, the presidential election is not won by the popular vote, but by separate electoral college contests in each state. According to a recent study by the Knight Foundation, in the crucial swing states where Trump won in 2016, the non-voters would, by a narrow margin, also tend to favor Trump if they did vote. It will be of little solace to many on November 4 if Joe Biden wins a popular vote margin twice the size of Hillary Clinton’s three million, on a wave of new voters in California and New York, but then loses the electoral college on a wave of new Trump voters in Arizona, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

The causes of social justice and the right to vote have been aligned in the United States since the nation’s birth, from Women’s Suffrage, to the Voting Rights Act, to today’s battles against voter suppression. As we face the unprecedented circumstance of a presidential election during a pandemic, the right to vote by mail has a new urgency in protecting Americans’ fundamental right to cast a ballot.

But as the disappointed candidates for school reform learned in June’s vote-by-mail test drive in Lockport, safeguarding voting and winning elections are not the same thing. Letting people vote from the comfort and safety of their homes may well entice the participation of a good number of those 100 million Americans who sat it out four years ago. But for those determined to use that vote to pry Donald Trump from the White House, it may only mean that the job of persuading those new voters will become all the more urgent.