Toward the end of Au Hasard Balthazar, Robert Bresson’s 1966 masterpiece, the long-suffering donkey of the film’s title falls into the clutches of a grain merchant. The face of the bit actor whom Bresson cast in the role is marked by the kind of ugliness that suggests spiritual deformity. His cheeks are gaunt; his hairline is receding. His prominent ears contrast noticeably with his beady eyes and thin lips. He delivers his lines in a clipped, matter-of-fact hiss. In one scene, we see him whipping Balthazar as the donkey trudges in circles, harnessed to a rotary gin, under a punishing summer sun.

Au Hasard Balthazar is Bresson’s adaptation Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, with the donkey as the saintly Prince Myshkin. But it cannot have been lost on the actor who played the merchant, Pierre Klossowski, that the animal he was sadistically whipping had been given the same name as his younger brother.

That is, Balthazar Klossowski, or as he styled himself, Count Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known by his childhood nickname, Balthus. While Pierre was on set with Bresson, Balthus was serving as the director of the French Academy in Rome. Balthus was everything his brother was not: handsome, wealthy, and internationally regarded as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century. He and Pierre had been estranged for decades. As a philosopher, novelist, translator, and artist, Pierre was a public figure in his own right, though, then as now, his celebrity paled in comparison to that of his brother. Today, Balthus’s canvases hang on the walls of MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, while Pierre’s books struggle to stay in print. It is only now, seventy years after it was written, that his first novel, The Suspended Vocation, has finally found its way into English, providing the occasion to reassess his subterranean, but nevertheless profound, influence on post-war fiction and philosophy.

*

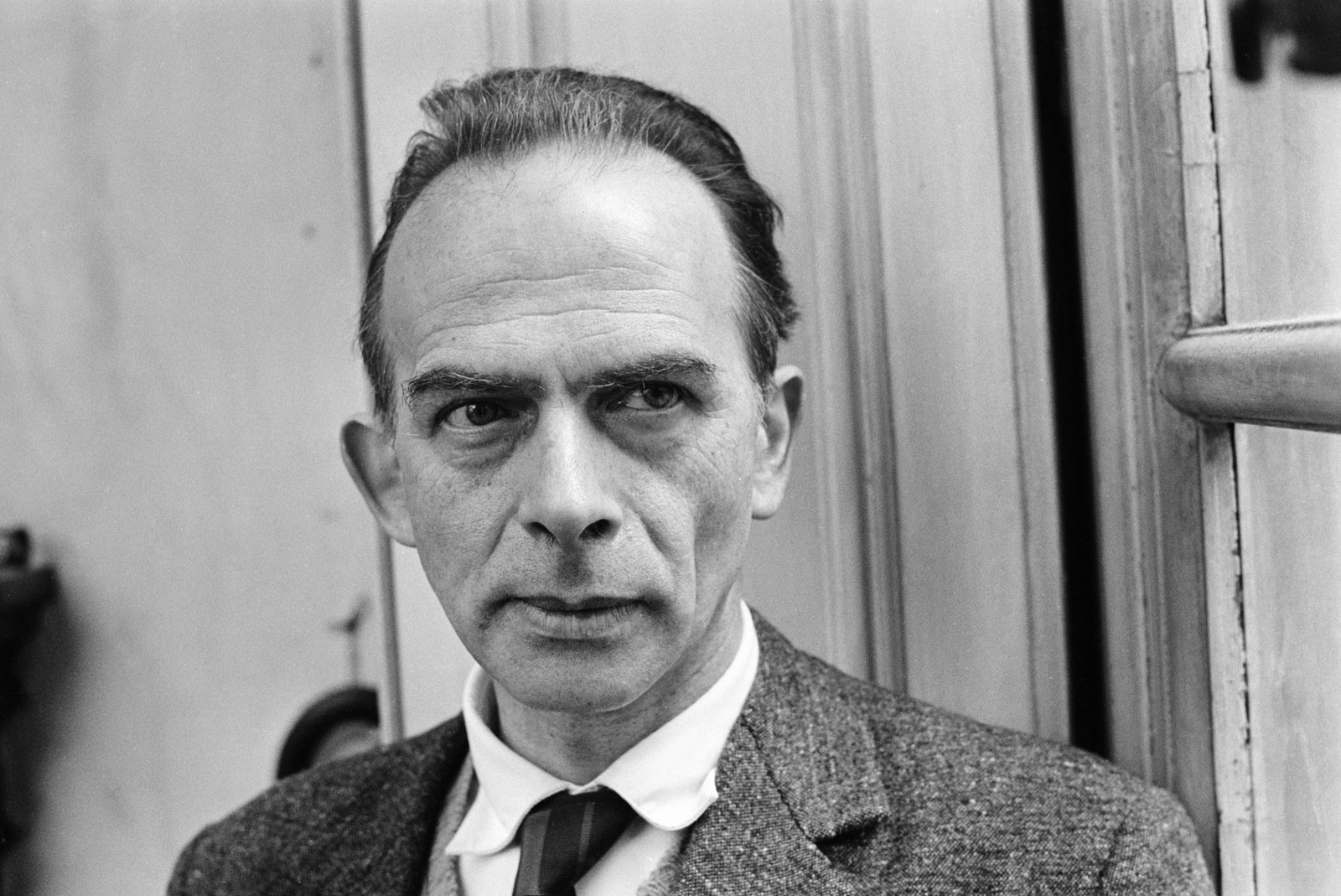

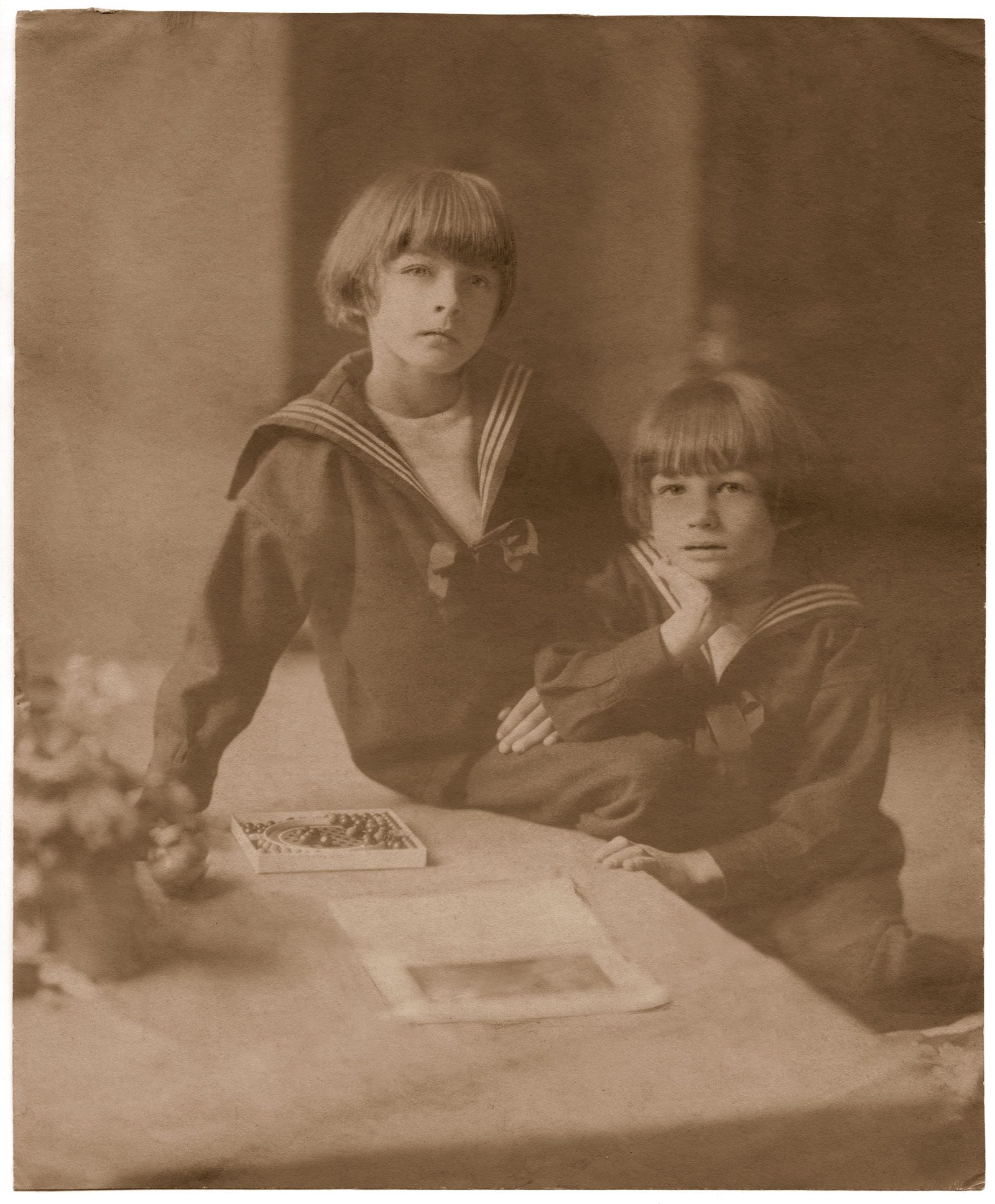

Pierre Klossowski was born in 1905 in Paris to Erich Klossowski, a Polish-German art historian and painter, and Baladine Klossowska, a painter of Russian-Jewish descent. Balthazar was born three years later. The boys grew up in bohemian Montparnasse, in a house whose walls were decorated with canvases by Cézanne, Delacroix, and Géricault, and which was frequented by notable artists, art dealers, and writers.

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, the family fled to Geneva, where Erich and Baladine separated. In Switzerland, Baladine began a stormy affair with Rainer Maria Rilke, a friend from their Paris days. Rilke would act as a surrogate father to the Klossowski boys, encouraging their artistic ambitions. Though it was clear he thought more highly of Balthus’s abilities, Rilke introduced Pierre to his friend André Gide, perhaps so as not to appear to be playing favorites. Pierre would act as Gide’s secretary and copy-editor during the years the writer was at work on his novel The Counterfeiters. Pierre even offered illustrations of his own—he, not Balthus, was the first to consider a career as an artist—but these were rejected by the author for being too sexually explicit. Pierre’s time as Gide’s secretary would provide him with the first of many experiences supplying ideas to other more famous men of letters.

The brothers spent the rest of the Twenties between Berlin, where Baladine’s brother lived, and Paris, though Balthus also spent time in Italy studying the frescoes of Piero della Fransceca, a significant influence on his pictorial style. In the Thirties, while Balthus began to exhibit the canvases he would become known for—from The Street (1933) to the Thérèse series (1936–1939), whose depictions of sexual assault and the sexuality of pre-pubescent girls continue to shock and outrage viewers—Pierre lived hand to mouth, working largely as a translator from German into French, and writing his first essays on the two philosophers who would be the lodestars of his intellectual career: Friedrich Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade. He befriended the philosopher and pornographer Georges Bataille, and became a member of Bataille’s ersatz secret societies, the Collège de Sociologie and Acéphale. It was likely through Bataille that he was introduced to Walter Benjamin, then a refugee from the Nazis in Paris. One of Benjamin’s most influential essays, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” was first published in Klossowski’s French.

*

Because of their mother’s Jewish origins, the fall of Paris in June 1940 posed a significant danger to Pierre and Balthus. Balthus fled first to the Savoie region, in unoccupied France, and then to Bern, Switzerland, the hometown of his first wife, Antoinette de Watteville. He spent the war years painting landscapes. Pierre, meanwhile, had had a crisis of religious conscience the year before and joined the Dominican order; his war was spent reading theology and working as a chaplain in a Vichy internment camp for political prisoners. He left the Church before Liberation and married Denise Marie Roberte Morin-Sinclair, a member of the Resistance and a survivor of Ravensbrück. Denise would be the model for her namesake Roberte, the central character in Klossowski’s novel trilogy The Laws of Hospitality (1954–1965), which sets out to systematically violate taboos against depictions of sexuality and violence in literature. It was a foundational work in the genre Michel Foucault called “transgressive” fiction, whose practitioners would go on to include such Anglophone novelists as. J.G. Ballard, Kathy Acker, and Dennis Cooper.

Advertisement

Foucault was particularly effusive in his praise of Klossowski’s work. “It is the greatest book of philosophy I have ever read,” he wrote of Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle (1969)—“on par with Nietzsche himself.” At the beginning of his publishing career, Klossowski had rehabilitated the Marquis de Sade’s reputation as a serious thinker in Sade My Neighbor (1947), which became a major point of reference for Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Blanchot, and Jacques Lacan; in his essays, he did the same for a philosopher whose work had been tarnished by its posthumous appropriation by the Nazis. Together with Living Currency (1970), which Foucault called “the greatest book of our times,” they provided the catalyst for the “critique of the subject” we now associate with French Theory. Many of Klossowski’s ideas were absorbed and given greater currency by better-known associates and protégés such as Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotard, and Barthes.

Klossowski may have appreciated the irony of this, and not just because of his experience living under his younger brother’s shadow. After all, the central insight of his philosophy was that Sade’s and Nietzsche’s atheism were notable less as breaks with Christianity as such than as ruptures within the Western concept of the subject. “The unique God,” Klossowski writes, functioned as “the guarantor of identities.” “[A]theism means that the principle of identity itself disappears along with the absolute guarantor of this principle; the property of having a responsible ego is therewith morally and physically abolished.” The name “Klossowski” was, to use his terminology, nothing more than a simulacrum. It did not really refer to a person, in the sense of a unified ego with a unique identity, but rather to a series of impulsive patterns that played themselves out at a specific corporeal site. Unintelligible in themselves, these impulsive patterns generated what he called “phantasms”—distorted images that could then be translated into the “code of everyday signs” of natural language.

Klossowski was one of the first philosophers to take Nietzsche’s observation that “every great philosophy…is a species of involuntary and unconscious autobiography” seriously. He interpreted Nietzsche’s and Sade’s writings in light of the particular phantasms generated again and again by the impulsive patterns he could, of course, not see. Applying the same method to his own work, if there is a single phantasm that haunts Klossowski’s career from The Suspended Vocation to Living Currency it is that of the double: the double agent, the parody, the counterfeit copy, in other words, the brother.

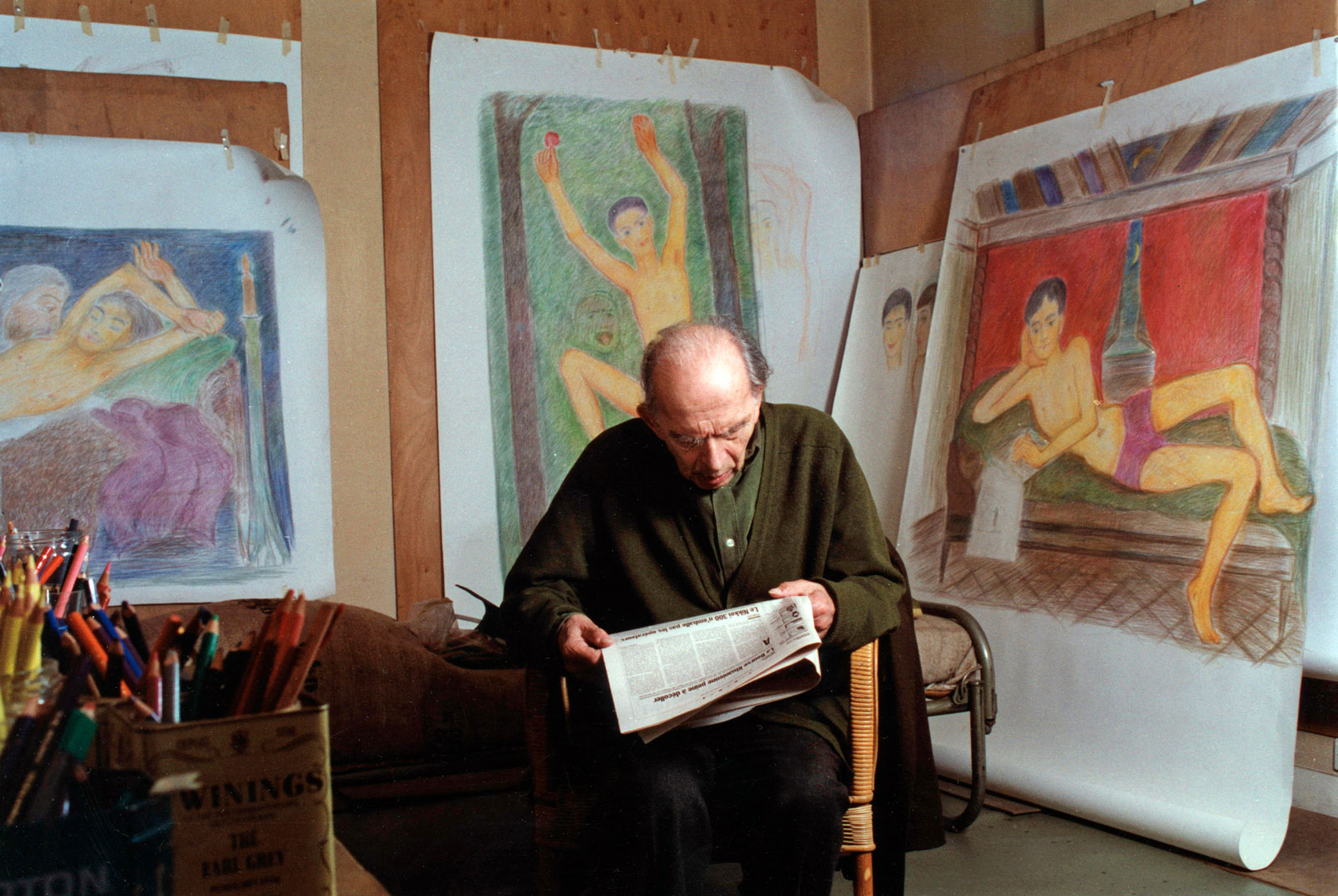

Nor did this phantasm express itself solely in writing. In the early Seventies, Klossowski turned his back on the medium of language to work in images drawn with colored pencils. He called his art a “mute conversation,” and it’s not difficult to guess with whom he thought he was having it.

*

Toward the end of his life, Balthus grew concerned about his artistic legacy. Having steadfastly refused to speak about his life—to the curators of a 1968 retrospective at the Tate he had sent a telegram that read, “NO BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS. BALTHUS IS A PAINTER OF WHOM NOTHING IS KNOWN”—he now began to invite prospective biographers to the Grand Chalet in Rossinière, Switzerland, where he lived with his second wife, Setsuko.

In his last years, he dictated a memoir to the journalist Alain Vircondelet. He proved to be an unreliable and repetitive narrator of his own life. His memoirs are largely concerned with defending his most famous paintings against the charge that they are effectively child pornography, which he does by denying, incredibly, that there is anything erotic about them at all. Otherwise, the apparent purpose of the memoir is to mythologize his family’s religious and class origins, gossip about famous friends, and settle scores with former rivals—above all, it seems, with Pierre. “People are surprised that I rarely speak of my brother,” he tells Vircondelet. “We have a strange relationship. Today I hardly ever see him, perhaps because our spiritual paths have diverged.” The precise nature of the divergence remains unclear, though Balthus alludes to the spiritual crisis that had prompted Pierre to enter the Dominican monastery some sixty years before.

Advertisement

Balthus’s assessments of his brother’s writings are patronizing: it is “transgressive work, not luminous enough.” Of the colored pencil drawings of his late period, Balthus is even less charitable. “I’ve never felt a real attraction to horror, ugliness and oddness. Perhaps that’s why there was a time when I didn’t appreciate drawings by my brother, whose imagination often dwells on what is morbid, perverse and sadomasochistic.” This, to be fair, is a not inaccurate assessment of Pierre’s drawings, whose depictions of sadomasochism border on the puerile, but such moralizing is rich coming from the painter of The Guitar Lesson, who has, not a few sentences before, compared his canvases to “children’s flesh lightly touched by angels.”

*

Thanks to translators Jeremy M. Davies and Anna Fitzgerald, we now have in English Klossowski’s first novel, The Suspended Vocation (1950), an oblique account of the spiritual divergence Balthus refers to. The Suspended Vocation is a hall of mirrors within a mise en abyme. Klossowski’s text purports to be a review of a book called The Suspended Vocation, an example of the “thesis novel” that was popular in France in the late Forties. Written anonymously, the non-existent novel was published by Bethaven, a non-existent Swiss firm. The reviewer describes the novel as a “fictionalized autobiography, a confession of the author’s religious experiences.”

It tells the story of Jérôme, a seminarian who must navigate the baroque theological controversies of a Church hierarchy riven by paranoia, factionalism, and terror. To this, Klossowski adds a further level of mediation, suggesting that the ecclesiastical setting of The Suspended Vocation is also an allegory of France during the Nazi Occupation. There is a sect called “The Devotion” and an ominous “Black Party” with ties to the Inquisition. Each of these groups in turn has rival subtendencies, but from one page to another their doctrines and members switch sides, seemingly at random.

This gives The Suspended Vocation the quality of a spy novel. No one is who they seem to be, no one means what they say, and the consequences of trusting the wrong person or saying the wrong thing are damnation, or worse, an appointment with the secret police. The thesis of this parody of a thesis novel seems to be: if the Devil can cite scripture for his purpose and make himself a perfect simulacrum of God, what’s to keep us from believing in him instead? The Suspended Vocation is what the novel looks like after Sade and Nietzsche, after the principle of identity that underpins realist notions of the consistency of character has melted away, and all men finally become brothers, indeed twins, because, perversely, there is no way to tell them apart. For readers who expect a novel’s plot to be grounded in its protagonist’s character arc—a series of conscious choices in response to an external conflict that causes the protagonist to realize and thus change some single, essential aspect of themselves by the conclusion of the story—this is one of the most frustrating and bewildering aspects of The Suspended Vocation. But it is precisely in this frustration and bewilderment that the reader comes closest to actually experiencing the dissolution of the “responsible ego” Klossowski and others would go on to theorize over a decade later.

The novel’s central scene involves Jérôme’s visit to a monastery, where he witnesses the painting of a fresco in the apse of its sanctuary. Klossowski describes the uncompleted fresco at length. It is a triptych that depicts scenes from the life of the Virgin, one of which bears a striking resemblance to a panel of Piero della Francesca’s Madonna della Misericordia, which Balthus would have recognized from his time studying the painter’s work in Italy, and which he had recently used as a model for the female figure in his painting The Room (1948). The name Klossowski gives the character kneeling in front of the fresco is simply Painter Brother—later revealed to be the inquisitor Malagrida, Jérôme’s “former rival,” his “foil” and “double” whose fresco, Jérôme comes to believe, serves to “mock [his] secret sins.”

*

When read in light of Balthus’s memoir, in which he refers to painting as his “vocation,” even the title of Klossowski’s novel takes on a resonance separate from the apparently religious meaning of the word. Art, as it turns out, and not Catholicism, as Balthus had implied, was Pierre’s suspended vocation. It is perhaps a fitting coda to their nine-decade-long sibling rivalry that just as Pierre had given up expressing himself in language to devote himself to pictorial art, Balthus gave up painting to express himself in language. The two had switched places, each to the other’s chagrin, as though they were characters in The Suspended Vocation. Klossowski’s novel concludes with a paradox: “Admittedly, our author has a singular way of confusing art with slander. How right is this proverb: The offender never pardons.”

And never did. Balthus died in February 2001, the year his memoir appeared, just short of his ninety-third birthday. Bono sang at his funeral, which was attended by the Aga Khan, the model Elle Macpherson, representatives from the French and Swiss governments, along with hundreds of other mourners. Pierre was not there. He died six months later in the Paris apartment he shared with Denise and has remained, to this day, in the shadow of his younger brother.

The Suspended Vocation is published by Small Press.