“Things are hard for me,” said Phil, my then-landlord, when he served me and my housemate, Conor, an eviction notice eight years ago. The three of us stood on the motley-colored gravel outside the house under the searing Sonoran Desert sun in Tucson, Arizona. Phil looked down and shook his head, as if he had just been roped into a funeral for someone he didn’t know.

Phil did not live in Arizona, and we scarcely ever saw him the year we lived there. He’d ignored our many complaints of the faint but stubborn stench of urine and fecal matter ingrained in the living room carpet from the prior tenant who owned numerous pets. Having reached breaking point, Conor pulled up the carpet in the name of sanitation and sanity. I gave my approval and even helped a bit.

Months later, Phil showed up for a surprise inspection. He walked in, took one angry look at our work, and clearly didn’t see it as a remedy for a health and safety issue; he saw it as an affront to his property and prerogatives as a landlord. There was nothing to stop Phil from throwing us out immediately. I read the document he’d handed us; the tone was aggressive, as if written by a sheriff, and it contrasted Phil’s demeanor of regret and helplessness. I had never even been late on my rent, but still, here we were: evicted.

I looked over at the house, white brick with cornflower-blue trim. It was the first place I’d lived in after leaving home, on the outskirts of town where I was born and grew up. Now I had to leave it in shame. I reassured myself: I’ll be okay, I can find another place. I was in my twenties, single, able-bodied. And if I had to, I could retreat to my working-class parents’ modest home across town.

Across the country today, millions of people might not be so lucky. They are now facing likely evictions as extra unemployment benefit payments and tenant protections, put in place during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, have been allowed to lapse by lawmakers. It won’t even take a bad landlord using the excuse of a shitty carpet—the US is looking at an imminent glut of mass homelessness, the like of which it has not seen since perhaps the Great Depression, of ordinary Americans who simply can’t make rent through no fault of their own.

*

Brian Goldstone, a journalist and anthropologist who is just completing research for his forthcoming book The New American Homeless, has been volunteering at an emergency housing hotline that mainly serves Atlanta residents, but also receives calls from all over the state, including rural counties, for people facing eviction. The vast majority of those affected whom he encounters are black and Latinx—although, he adds, he’s now starting to see even single white men, including tech company workers laid off during the pandemic. According to the Urban Institute, between February and April, one out of every five rental households nationwide had at least one member who lost a job.

“This is only an amplification of a problem that was already taking place before coronavirus,” Goldstone said.

Some experts’ fears earlier in the pandemic have now been borne out. “We don’t want what was originally a health crisis turned into a job crisis then now to become a housing crisis and a crisis of housing instability as people are evicted from their homes,” said Ingrid Gould Ellen, a professor and faculty director at the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at New York University, quoted by Vox in July.

When Covid-19 arrived in the US this spring, it changed the housing landscape overnight. By late March, when the public health crisis engulfed the US, hundreds of grassroots mutual aid networks had emerged around the country, in virtually every state. They could hardly do enough, but they did help many vulnerable people. And it was many of these same aid networkers who also demanded a moratorium on evictions. In one sense, they appeared to be pushing an open door: numerous authorities at city, state, county, and federal level ordered halts on evictions, based in part on the pressing need for people to stay isolated at home to tamp down community transmission of the coronavirus.

But some commentators saw fundamental flaws in these measures from the beginning. Despite the moratoriums on evictions by authorities in the public sector, for example, few officials seemed concerned that private-sector banks were let off the hook—even though “that’s where most of the evictions and foreclosures will occur,” said Joseph Stiglitz, the former chief economist for the World Bank and a senior economic adviser to Bill Clinton, back in March. As he noted in his 2019 book, People, Power, and Profits, three in five Americans do not have the cash reserves to cover a $1,000 emergency.

Advertisement

Part of this pattern is familiar from the Great Recession of the 2000s that preceded my eviction. Writer and activist Laura Gottesdiener records in her book, A Dream Foreclosed: Black America and the Fight for a Place to Call Home, that evictions and foreclosures by banks shuttered homes to some 10 million people between 2007 and 2013. This amounts to the combined populations of Oklahoma, Mississippi, Wyoming, Vermont, and New Mexico.

But that affected mainly homeowners—the role of banks meant little in the rental market, since the landlords there are not banks but big realty landlords, which are now often private equity firms or hedge funds. These new residential real estate tycoons swooped into the wreckage of the 2008 recession and bought up—through foreclosure auctions and bulk loan sales—some 200,000 distressed mortgages in the years after the housing crisis. A 2016 study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that “institutional investors in Atlanta were 18 percent more likely to file evictions than small landlords.”

Goldstone points out that the CARES Act covered only a third to a quarter of US rental properties. Most tenants remained vulnerable. “That means that about 75 percent of ordinary people renting properties in the US were not covered by the federal moratorium on eviction,” Goldstone said. Even where bans did apply, enforcement of the moratorium was spotty: according to ProPublica reporting, landlords were found to have violated the order in Florida, Georgia, Oklahoma, and Texas.

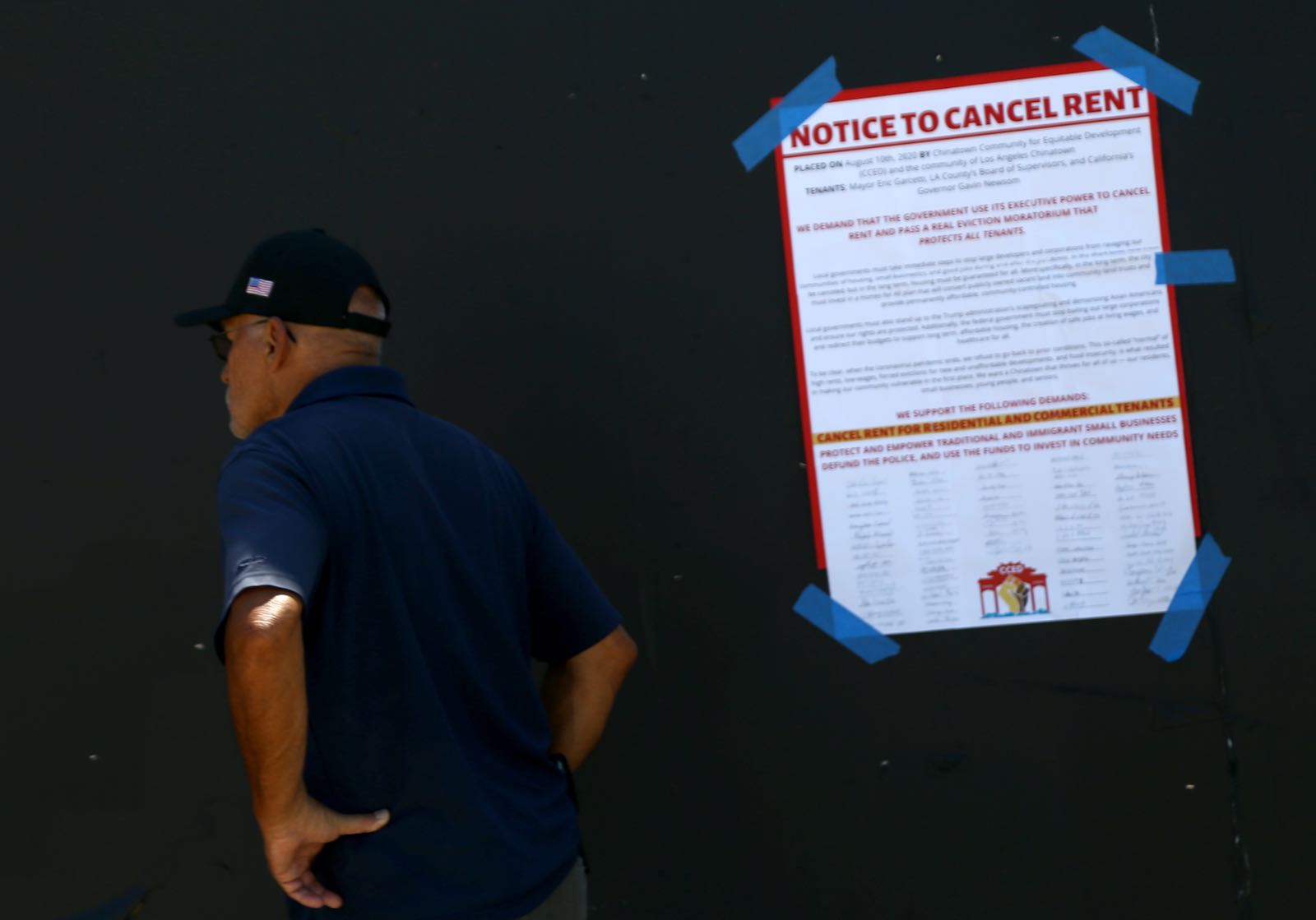

Meanwhile, the rent strikes started spreading. By April 1, one third of Americans couldn’t make rent. Rent strikes organized nationwide on May 1, International Workers’ Day, were by some accounts the largest in US history. Communities have organized eviction resistance actions from Kansas City, Missouri, to New Orleans to New York City—the latter now “the epicenter of a growing tenants’ rights movement,” according to a Wired report.

But now, with the easing of pandemic restrictions—done prematurely, according to many health experts—several states have seen sharp spikes in Covid-19 cases. By late June, the hotspots were Texas, Florida, and my own state, Arizona. By late July, Texas, Dr. Deborah Birx of the White House Coronavirus Task Force nicknamed Florida, Texas, and California “three New Yorks.” Rural areas throughout the US, which had seemed to escape the first wave of infection, have now been particularly hard hit. And it’s here, where migrants and the undocumented are often the essential workers planting and processing our food, that the pandemic has created severe housing insecurity. “Rural homelessness and rural housing insecurity is notoriously ignored,” explained Goldstone. “The population is set to expand and grow dramatically over the coming months.”

In Arkansas, for example, poultry tycoon Ronald Cameron “gave nearly three million dollars to organizations supporting Trump’s candidacy,” donations that contributed to lax oversight of how such companies are protecting and paying workers during the Covid-19 crisis. Richard, an immigrant from the Marshall Islands, found work at a Tyson poultry-processing plant in Springdale, where he was employed for about eighteen months (at his request, I am using only a first name). When, on June 8, 2020, he had his temperature taken at work (a rule put in place to screen for coronavirus), it was running high. The company required him to get tested and stay home while he was waiting for test results—but, he said, refused to pay him in the interim.

A month later, Richard still hadn’t received his test results. He and his wife and two children had not been able to make rent, and in July, they received a threat of eviction. He had asked his wife to communicate with Tyson for him since she spoke better English, but to no avail. A Tyson spokesperson said that, since March 13, the company had eliminated any waiting period for short-term disability benefit, and increased coverage to 90 percent of full pay, for those with Covid-19 and those who were symptomatic but had not yet been tested.

Eventually, Richard was able to get another job, and, with financial aid in the interim from the local Marshallese community, the family avoided eviction. But other chicken-processing and agricultural workers in rural Arkansas discussed facing eviction either because they’d been fired after testing positive for Covid-19, or because they were paid only a certain percentage of their full wage while in quarantine after testing positive, or because they had had their hours cut because of the pandemic.

Advertisement

Southern Arizona is already suffering among the highest rates of poverty in the country. Growing homelessness exacerbates other inequalities during the pandemic. According to the Arizona Health Department, the border community of Yuma, for example, where close to one in five people live in poverty—a rate markedly higher than the rest of the state and the US as a whole—has experienced double the rate of Covid-19 fatalities compared with prosperous Maricopa County (which encompasses Phoenix).

“People are being evicted without being allowed to go into court for their hearing,” Sabrina Fladness, a tenant lawyer in Tucson, Arizona, wrote me on Facebook Messenger. The Pima County Consolidated Justice Court at first said the measure applied only to symptomatic people. “But eventually, they stopped allowing all people into the court (even attorneys seeking to review case files),” despite constitutional due process, Fladness wrote me, in an email. Tucson ranks twenty-fifth on Princeton University’s Eviction Lab database of “top evicting areas” in the United States, and most of those ahead of it on the list are located in the American South.

*

Because it was early in 2011 when I was evicted, I recall thinking when the Occupy Movement hit a few months later that year: “With more housing hardship on the rise, how will the Occupy Movement include those hardest hit?” I had not, back then, come across any local movement organizing on behalf of tenants under housing duress. Some of the movement’s strongest proposals from its New York epicenter, such as “Occupy Our Homes,” clearly didn’t reach the rest of the country all at once, but did so in some places like Minneapolis.

Tenant rights activism has taken several years since then to reach fruition, but its ideas have now become part of the progressive legislative agenda. From Bernie Sanders’s Housing for All plan, to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s A Place to Prosper Act, to Ilan Omar’s proposal to cancel rent during the pandemic, there is more cause today for hope.

There is also greater cause for worry, even for solidly middle-class Americans. The decade to 2018 saw a steady rise of renter households with incomes between $15,000 and $75,000 were “cost-burdened”—in other words, paying more than 30 percent of household income on rent—from nearly 80 percent of those at the bottom of the income bracket, to more than a quarter of those earning up to $75,000. Perhaps as a consequence, some of the hardest-hit communities, such as undocumented immigrants who were shut out of the CARES Act stimulus, aren’t waiting for the grindingly slow political process. In Phoenix, Arizona, for example, a radical group called Trans Queer Pueblo (TQP) is organizing in what has become one of the country’s latest coronavirus hotspots.

The group counts about three hundred and fifty members, mainly LGBTQ+ undocumented and documented migrants of color who work in restaurants, factories, daycare centers, or do sex work. One of TQP’s project coordinators, Stephanie Figgins, who is the daughter of a Peruvian immigrant, explained that many of its members face difficulties finding housing everywhere they go. They experience, she said, “This deeply insecure situation of housing in their countries from colonialism and imperialism, and then this deeply insecure situation of housing in detention—of not being in control of your body, autonomy, anything—and then coming out and facing more housing insecurity. And on top of that, Covid, and even more insecurity.”

The group has so far raised $200,000 to cover members’ rent and groceries. It has also created a Mutual Aid Committee, which everyone who’d received the fund’s assistance was invited to join via weekly Zoom calls.

One member, Valeska, is a trans woman from Guatemala. The group came into contact with her in January 2019 when she was in La Palma detention center in Arizona. That facility made national headlines this year for being the site of one of the largest coronavirus outbreaks in an ICE center in the country. TQP helped get her out of ICE detention and provided her with health care, including hormone treatment she needed. She soon joined the group herself.

When the pandemic hit, Valeska became a beneficiary of the relief fund and joined the Mutual Aid Committee. But TQP’s resources are stretched thin, and in June, the group couldn’t get her rent money until a few days after the first of the month. She lived in an apartment complex whose management was unsympathetic about late payment, and faced the threat of eviction. Because she paid the rent late, she was slapped with a $150 fee. Since she’s already lost her job and had no income, she was forced to do sex work to cover that sum to keep her home.

She’s grateful to be able to count on support from TQP in the future, but if she needs extra help that the group can’t provide, she would do the same again, if she had to. “I would find some other way,” she said. “Whether selling my body or doing whatever I had to do to get the money.”

*

Renters who enjoyed some measure of protection are now at risk of eviction since the moratoriums on eviction are coming to an end at both federal and local levels. (On September 4, an order issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention came into force that appeared to bar evictions until the end of the year. However, the order only has force if tenants provide a written declaration, under pain of perjury, of financial hardship and risk of homelessness; it also provides no rent relief to tenants; nor does it prevent landlords from charging interest on arrears or using available legal measures to collect unpaid rent after the order expires, on December 31.) In practice, many tenants no longer have protection from eviction, and in the coming months, up to 28 million people could be thrown out of their homes, according to estimates by Emily Benfer, a law professor who has collaborated with the Eviction Lab.

“While eviction is a threat for people with resources, the risk of homelessness is much bigger for people at the bottom of the ladder,” Goldstone said. “For low-income people of color, this has been a crisis. The scale and scope and magnitude in this country is likely going to be in the coming months something that we’ve never seen before.”

While researching his book, Goldstone followed people living in an extended-stay hotel in Atlanta—“It is, in effect, an emergency family homeless shelter that is also very exploitative and profitable.” Between hotels and shelters, Goldstone has seen some striking trends. “Pretty much everyone is coming out of an eviction or has an eviction already, and that is a main barrier to securing stable housing.”

He dubs this growing social class of Americans “the working homeless.” These are people who are not homeless for lack of employment but find themselves trapped in a vicious circle—on such low incomes that approval for a regular rental is almost impossible to come by, especially with a record of a past eviction. Instead, they are forced to watch “all their wages going to not being evicted from that hotel.”

After my 2011 experience, I have some sense of what it means to belong to this class. And many people are only a paycheck—or an unemployment benefit check—away from joining it. I don’t exclude myself: like many other journalists, I’ve lately faced a dearth of assignments and reduced income, and couldn’t make rent on time last month; nor this month, either. Luckily, unlike eight years ago, my landlords today are longtime friends, who were willing to offer me rent forbearance when the crisis hit. So, although I was behind until I could grub up more funds, I’m not in immediate danger of losing my place.

As landlords become less likely to take on tenants they perceive to be at risk of defaulting on their rent, Goldstone said—in particular, those who, like me, have an eviction on their record—the new working homeless class will grow. According to a Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau, covering the period July 16–21, about one third of respondents said they were unsure whether they could make August rent. More than a quarter said they were late on July rent payments. More than 31 million Americans have filed jobless claims.

The moratoriums have demonstrated—if only temporarily—the potential of better public safeguards for tenants. As it stands, though, laws overwhelmingly favor landlords over tenants. The housing-insecure are of necessity extremely resilient, but they shouldn’t have to be. It’s a choice that American society has made to allow predatory landlords to profit off economic hardship. We could change that.

Alice Driver contributed additional reporting. The Economic Hardship Reporting Project helped fund this story.