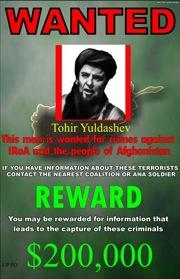

Most of the reports about the Pakistani Army’s offensive in Waziristan have mentioned the Islamist extremists from Uzbekistan hiding out there—but they’ve often done so without really explaining what’s up. If you follow the coverage closely enough, you might learn that the Uzbek militants are tough fighters much feared by the Pakistani military, that they’re loyal auxiliaries of al-Qaeda who have displayed little inclination to negotiate, and that they’re being targeted by both the US and the government in Islamabad for these same reasons. The Uzbek Islamist leader, Tahir Yuldashev, was killed by a U.S. drone strike in Waziristan in August of this year—which says a lot about how seriously the Uzbeks are taken both by the US and the Pakistanis (who probably supplied the CIA with the information needed for the hit).

But how did they get there in the first place? It’s not an insignificant question: From Tashkent (Uzbekistan) to the Pakistani capital of Islamabad is roughly 700 miles—comparable to the distance from New York to Chicago.

The story begins in the Ferghana Valley, a remote but thickly populated part of Central Asia where three ex-Soviet republics (Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan) overlap. I first ran across the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) during a reporting trip to Ferghana back in 1998. I was interviewing the families of Islamic activists whose sons and husbands had been rounded up by the government in response to a series of mysterious killings of local security officials. Credit for the attacks had been assumed by the IMU, a group claiming to be a new regional Islamist guerilla movement—apparently including some of the very same radicals who had openly defied Uzbekistan’s brutally secular dictator, the ironically named Islam Karimov, in public demonstrations in the Ferghana in the early 1990s.

These radicals had tried to establish sharia law in several Ferghana towns before being ousted by the Uzbek government. Some were arrested and sent to Uzbekistan’s concentration camps (set up to stamp out political opposition in the 1990s), but the ones who escaped soon found a new cause in neighboring Tajikistan, where they joined the country’s homegrown Islamists in a savage civil war against neo-communists (1992-1997). Then, in 1999 and 2000, the IMU made headlines by staging raids into Kyrgyzstan through the Tien Shan Mountains. They also took hostages—a group of Japanese geologists in 1999 and American tourists in 2000. At the time, the group’s military leader was a ruthless ex-paratrooper who found religion during his years fighting in the Red Army in Afghanistan. His nom de guerre was Juma Namangani.

In the meantime the IMU had also been casting its gaze farther afield. One of its major sources of income involved its control of some of the heroin-smuggling routes leading into Central Asia from Afghanistan. At some point the Pakistani military intelligence service, the notorious ISI, got wind of the IMU’s activities and realized that here was an ideal proxy in the region for Pakistan, which was at the time aligned with the newly-ascendant Taliban. By the late 1990s the Afghan warlord Ahmed Shah Massoud was barely hanging on in his struggle against the Taliban, and sponsoring the IMU provided a way for the ISI to put additional pressure on him from the north. By the beginning of this century some Uzbek militants had joined up with al-Qaeda in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, where they gained a reputation as particularly fierce fighters.

In the period right after the September 11 attacks, many Uzbek guerillas in Afghanistan—including Namangani, who was killed in November 2001—were shredded by U.S. air attacks, and some ended up at Guantanamo. But others survived for years—including the IMU’s spiritual leader Tahir Yuldashev. Along with other remnants of the Qaeda coalitions, these fighters migrated into the tribal areas of Pakistan, where they remain today, notwithstanding the killing of Yuldadshev. (Interestingly, the Uzbeks do not have any particular ethnic connection to Pashtuns, the dominant group in the Taliban areas of southern Afghanistan and the tribal areas of Pakistan. It’s more an ideological affinity: the Uzbek Islamists have been brutalized and hardened by their war with Karimov’s dictatorship, and that tends to make them favor a radical takfiri Islamist line, much like the jihadis in Pakistan and elsewhere.)

According to Ahmed Rashid, the number of Uzbek fighters in Pakistan has actually grown in the intervening years. He thinks they may now number in the low thousands, as more and more disaffected youths flee the poverty and religious persecution of the Central Asian republics for the dream of an Islamist oasis in Waziristan. In recent months there have also been ominous reports of scattered guerilla attacks across Central Asia that some observers have attributed to the IMU. The evidence of a comeback outside of Pakistan is still inconclusive. But if the Pakistanis asked the Americans to target Yuldashev for assassination in August, that suggests that the IMU is being taken quite seriously by the army leadership in Islamabad. We still don’t know how many Uzbeks are in Waziristan, how determined they are, or how well they fight. But we could soon find out.

Advertisement