Now that the World Cup is over and the Spaniards and everyone else who admired their elegant way of playing soccer is happy, and the few nations whose teams either exceeded expectations or did okay in the month-long tournament have returned to their normal lives, the fans in underachieving countries are still fuming, many of them destined to recall for the rest of their days how their side either disgraced themselves, or were the victims of gross injustice. For those of them that have been following their national team for years, they’ve most likely already suffered more than any holy martyr in the history of the church, and yet it’s doubtful that even one of them will go to heaven, because they cursed and swore till they were blue in the face each time their team lost.

I speak from experience. The first World Cup I followed closely was held in Brazil in 1950 where Yugoslavia, the country I was rooting for, was eliminated from the cup by the host nation with the score 2-0 in front of 142,000 spectators in Rio. I still remember that the Brazilian goals were scored by Ademir and Zizihno and that our top player, Rajko Mitic, injured his head before the game as he was exiting the tunnel that led to the field, which, needless to say, was the sole reason we lost. After I listened to the game on the radio, or rather tried to listen to it since the broadcast was live and full of static, I couldn’t fall asleep for hours afterwards hoping vaguely that the next morning, when I bought the newspaper, the score would be different and we the winners.

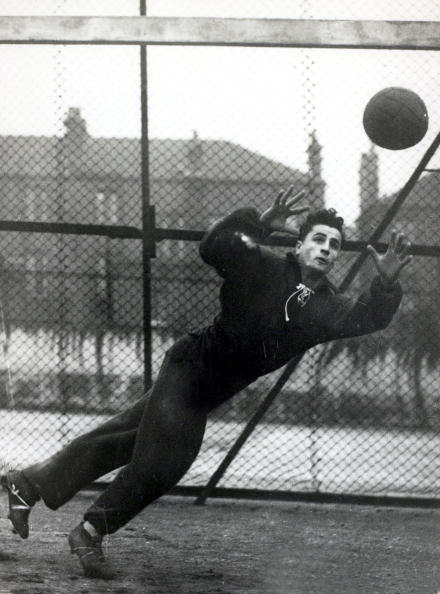

Although I was only twelve years old, I already had my own view of how we should play the Brazilians and which players should be on our team. I don’t remember the particulars, but I imagine I wanted them to shoot all the time. We played soccer in the street with a ball made of rags, which one really had to kick hard, so dribbling around defenders and shooting is all we knew. (Yugoslavia had a star player, Dragoslav Šekularac, who played with me a few times in the street. He was a dribbler in the style of Lionel Messi and they always said it was because he started with a rag ball.) One of my teachers, who ordinarily regarded me as a numbskull, once called on me in class before an important game and said that he heard I knew a lot about soccer and wanted my opinion. I rose in my seat and delivered a lengthy lecture about our chances against Russia and had the teacher’s and the class’s undivided attention.

There are kids and grownups like that in every country where soccer is an obsession. Months before the World Cup, they argue with friends over the chances of their national team, alternating between high hopes and premonitions of utter failure, which is what most of them got. (I myself wanted Serbia to win, but I knew their attack was too slow so they wouldn’t go far. Otherwise, being a fanatic Arsenal fan for many years, I have no energy left after the long English season to root for any national team. I just love to see a well-played game.) This, as far as I’m concerned, is one of the great unsolved mysteries of the universe: how is it possible that eleven more-than-competent club players, who stand together before the start of the game with solemn faces and even tears in their eyes as the national anthem is played, turn out to be completely clueless during the next ninety minutes on the field? How could France self-destruct, England play such uninspired soccer, Italy be so predictable, Brazil fall apart after some rough play by the Dutch, Argentina, who until that moment appeared invincible, watch helplessly as the Germans scored four goals?

The obvious explanation, that a better team won that day, is never good enough for the tens of millions of disappointed. Here, then, are some excuses the fans universally rely on to explain defeat:

- It was all the fault of the referee. He was either incompetent, or was pressured not to see what was being done to us, since the FIFA leadership and the big money aligned behind them have their own ideas about whom they want to see in the final.

- Our coach is an idiot. He left our best players at home or on the bench, ordered the team to attack when they ought to have played defense, and made them play cautiously when they ought to have gone for broke.

-

Our players are overpaid prima donnas who are unable to fully concentrate on the game because they are thinking about their girlfriends, their vacation homes, and the millions in their bank accounts.

-

For the nationalists, the decline of the nation is the primary cause. Immigrant players of all races have diluted the native stock and turned us into a bunch of sissies. We no longer know how to work and fight together as we once did.

Except for the completely inane reason four, these excuses each contain an element of truth. Thanks to modern technology and the ability of TV broadcasters to show every play from multiple angles, the bad calls of the referees, which are not unusual in soccer, looked in this World Cup even more outrageous and costly than usual—as indeed, they often were. Among the coaches, even some of the best, like England’s Fabio Capello and Brazil’s Dunga, failed to read the game in decisive moments and to make right tactical substitutions. As for the lackadaisical way in which whole teams and many star-players performed, what were these men on the sidelines supposed to do?

Advertisement

Maradona, the Argentine coach, hugged and kissed each player, like an old friend he hadn’t seen in years, after he scored a goal or was substituted, but these public declarations of love did not help his side against the Germans who always seemed to be exceptionally motivated even though their coach, Joachim Löw, sat through most of the games with no expression on his face. In France, following the team’s early-exit fiasco, the legislature initiated an inquiry and President Sarkozy summoned one of the older players on the team for a tête-à-tête at the Élysée Palace. What a waste of time when every waiter and taxi driver from Paris to Marseille already had the answer: the national coach—who apparently relied on an astrologer to guide his selection and tactics—was a pompous half-wit.