When the Beatles called on Elvis at his rented Bel Air mansion in August 1965, the odds of a pleasant evening were always going to be long. Whereas the Fab Four, with five number one albums behind them, were currently basking in the high noon of their creative prime, Elvis had spent the past half-decade squandering his prodigious talents on awful movies and now, at only thirty, looked to be in permanent eclipse. And so, having taken a seat beside a sun-bronzed Elvis on the sofa—where, like any other night, he was simultaneously watching TV with the sound off and listening to music—John, Paul, George, and Ringo suddenly found themselves with nothing to say. “If you guys are just gonna sit there and stare at me,” said Presley at last, “I’m goin’ to bed…I didn’t mean for this to be like the subjects calling on the King.”

The evening seemed to turn a corner, though, when Elvis proposed a jam session and summoned the guitars. “This beats talking, doesn’t it?” said John Lennon, once the music was underway and it seemed as though they would get along after all. Later, however, Lennon began to press Elvis on why he’d abandoned rock ’n’ roll for Hollywood. The star of Tickle Me and Kissin’ Cousins bragged defensively: “I’m making movies at a million bucks a time and one of ’em—I won’t say which one—took only fifteen days to complete.”

“Well, we’ve got an hour to spare now,” replied Lennon, unable to help himself. “Let’s make an epic together.” Elvis did not take the jibe well and things apparently devolved from there. According to the journalist Chris Hutchins, who was present at the meeting, when the Beatles finally left at around 2 a.m., Lennon is reported to have said to his host in the Inspector Clouseau accent he’d been slipping in and out of all evening: “Sanks for ze music, Elvis. Long live ze King!” The two rock ’n’ roll Olympians would never meet again.

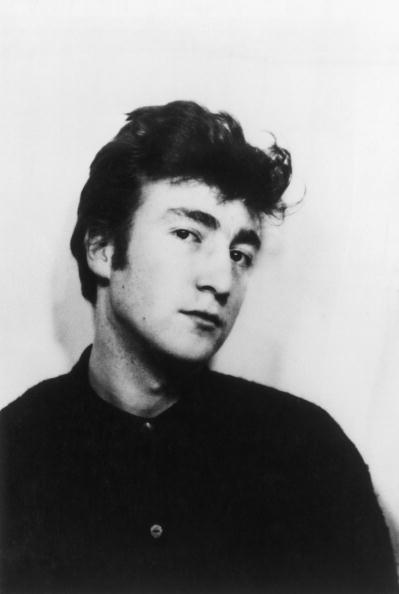

As everyone in Christendom is surely aware, we are currently in the thick of Lennon anniversary season: October 9 would have been his seventieth birthday and on December 8 it will be thirty years since he was murdered outside his home in the Dakota on Central Park West. But this particular Lennon—a kind of Shakespearean fool who relished taunting the King over his abject decline—is largely missing from the recent rash of hagiography, which gives us Lennon the incorrigible teenage rebel, Lennon the ardent peace activist, Lennon the contented family man, but not much of Lennon the unappeasable misanthrope, the man who in “Yer Blues,” from The White Album (1968), takes a running kick at the universe itself. Lennon was a spiky and unpredictable character, but we can be fairly sure he would have viewed the latest array of dewy-eyed commemorabilia with a mixture of impatience and contempt. His impulse was to desecrate idols, not prostrate himself before them.

Nowhere Boy, a young-Lennon biopic directed by the British photographer and conceptual artist Sam Taylor-Wood, has a good go at shining a light into the dark places of Lennon’s soul, but is ultimately undone by its determination to make him likable. A compendium of facile ironies, the film presents us by turns with an array of soppy-stern oldsters telling the wayward young Lennon (played by Aaron Johnson) that he will never amount to anything; an old girlfriend calling Lennon “a loser” moments after he’s been denied access to the Cavern Club (where the Beatles would soon be discovered by their future manager, Brian Epstein); Lennon cursing God for not making him Elvis, and swearing he’ll one day get even (with God, that is, not the King). All this is interspersed with melodramatic flashbacks to the day when a five-year old John was forced to choose between his emotionally unstable mother and largely absentee father (a merchant seaman who was then about to leave England permanently for New Zealand).

The result is a tedious game of psychological connect-the-dots, as the young singer-songwriter’s artistic fire and drive are shown to be a direct consequence of his troubled past. And while the film certainly shows Lennon getting into lots of trouble—riding around Liverpool on top of a double-decker bus, bunking off and getting suspended from school—it tends to side with him all too snugly. When he throws the rattle out of the pram at his mother’s wake (she was hit by a car in 1958) and punches a band mate before storming off, he is allowed to atone almost immediately, as he returns and tearfully wails, “I’m a shit! I’m a shit!” Somehow the Lennon of Nowhere Boy just isn’t nasty enough.

Advertisement

However submerged they may have been at the start of the Beatles’ career, nastiness, mischief, and a penchant for misrule were always the main ingredients of Lennon’s genius. Brian Epstein, their upper-middle class, RADA-trained manager, took the foul-mouthed, sweat-drenched, leather-clad foursome he heard singing in the Cavern Club in 1961, cleaned them up a little (suits, ties, synchronized bows), and set them on their way, but the chaotic and irreverent vitality at the band’s core was never that far from the glossier surface. “For our last number, I’d like to ask your help,” Lennon said in a celebrated moment from the 1963 Royal Variety Performance to an audience that included Queen Elizabeth and the Queen Mother. “Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands. And the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewelry.”

It is Lennon’s simmering mania and anguish that make the early albums so thrilling. Listen to his raucous howl on the band’s psychotic version of “Money (That’s What I Want)” from With The Beatles (1963), or the way in which the tame, almost mincing verse of “I’m a Loser” (from 1964’s Beatles for Sale) erupts into the startlingly savage chorus. After Revolver (1966), aided by vast quantities of LSD, this mania and anguish came to a boil and Lennon wrote his greatest songs—“A Day in the Life,”* “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “I Am the Walrus,” “All You Need Is Love,” “I’m So Tired,” “Yer Blues,” “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” “Don’t Let Me Down.” For someone like myself, born several years after Lennon’s murder, it is difficult to believe there was a time when these songs didn’t exist: they seem like a part of nature. The Beatles “got there first,” Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys said after first hearing “Strawberry Fields Forever” on his car radio, an experience that is reported to have led to his abandoning the legendary Pet Sounds follow up, Smile.

One of the other glories of late-era Beatles is the gleeful manner with which Lennon goes about vandalizing the chipperness of various McCartney tracks. To the chorus of McCartney’s “Getting Better”—“It’s getting better all the time”—Lennon adds the dementedly high-pitched and utterly characteristic backing vocal, “It can’t get no worse.” On the jolly “Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da” (which Lennon denounced as “Paul’s granny shit”) he contributes a lot of sinister and derisive laughter and at 2:34, after McCartney sings the line “Molly lets the children lend a hand,” can be heard to querulously say “Foot!”

The conventional Lennon NYC (directed by Michael Epstein) is not much better than Nowhere Boy. A documentary about the post-Beatles years Lennon spent in New York from 1971 until his death in 1980 (as well as the so-called Lost Weekend he spent in L.A. in 1973), the film gives us the usual splicing-together of archival footage and wizened talking heads, none of whom say anything remotely unexpected. Mostly they praise his seventies’ solo albums for being personal (“He projected himself, he projected his guts,” etc.), which was in fact one of their greatest limitations. “Mother” (from the 1970 John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band), written under the influence of primal scream therapy (“Mother, you had me but I never had you”) is always a chore, never a pleasure to listen to: the screaming at the end, however rebarbative, feels put on and perfunctory compared to the spontaneous howls and yelps one hears throughout the Beatles’ catalogue.

Without McCartney, Epstein, or his own earlier glossy public image to chafe against and subvert, Lennon was like a bull in search of a china shop. The one great thing he did find to oppose was the Vietnam War. This, however, brought a fatal sloganeering quality to the music (Lennon NYC contains a highly irritating concert performance of “Give Peace a Chance,” in which Lennon and Yoko tunelessly shout the chorus at their audience through a megaphone). His anti-war activism also lead to years of FBI surveillance and efforts by the Nixon Administration to have him deported. One of Lennon NYC’s most memorable moments comes when Lennon emerges from a New York courthouse in 1975 having finally been granted his green card. Asked by the press if he bears a grudge against Nixon & co. for the shoddy treatment he’d received, he smiles and, without missing a beat, says in classic Lennon fashion, “Time wounds all heels.”

* Though of course the interpolated bridge (“Woke up, got out of bed,” etc.) is McCartney’s.