On November 29, a conservative website posted an 11-second clip of ants crawling over a crucifix from a 4-minute video made by David Wojnarowicz, an artist who died of AIDS in 1992. The video, Fire in My Belly, was part of a show at the National Portrait Gallery called “Hide/Seek,” said to be the country’s first national exhibition devoted to gay and lesbian themes. Wojnarowicz made the video in 1986 and 1987, as his lover Peter Hujar was dying of AIDS, and as David himself learned that he was HIV-positive; it is an eerie meditation on life, death, violence, and nature, featuring imagery from the Day of the Dead. David later explained that he saw Jesus as a symbol of someone who willingly took on the suffering of the world. A self-appointed conservative guardian of public morality, William Donohue of the Catholic League, saw it differently, and attacked the video clip as blasphemous and demanded that Congress reconsider future funding of the Smithsonian in reprisal. The Smithsonian—which runs the National Portrait Gallery and which is funded by the US Government—promptly removed the video from the exhibition, effectively granting Donohue a “heckler’s veto.”

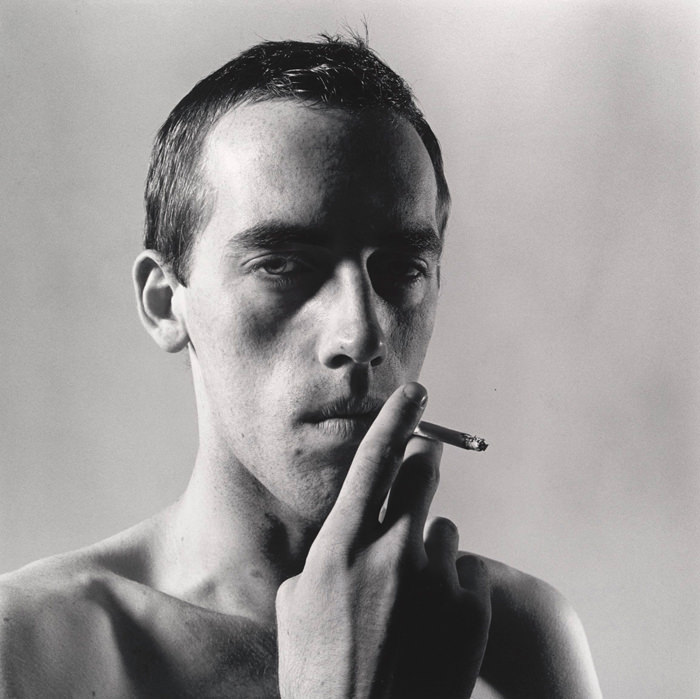

About twenty years ago, a gaunt, respectful, but angry David Wojnarowicz walked into my office at the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York to ask what could be done about a flier that Donald Wildmon of the American Family Association had just sent out to every member of Congress, all major newspapers and TV networks, and thousands of religious ministers throughout the country. The flier featured images of gay male pornography, and claimed that they were David Wojnarowicz’s art, funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. The claim was blatantly false. David had incorporated small “found” images from gay male pornography in a series of life-sized collages devoted to the challenges of living as a gay man in the 1980s, in a community ravaged by AIDS and beset by condemnation, prejudice, and hatred. But Wildmon had reproduced only the pornographic images, stripping them from their context in the collages, and blatantly twisting the facts to further his homophobic propaganda.

We sued Wildmon, and in 1990, a federal district court ruled that he had violated David’s rights under the New York Artists Authorship Rights Act, which forbids the misrepresentation of an artist’s work. The court ordered Wildmon to cease sending out any further fliers, and to deliver a correction to everyone who received the original flier. Because David’s work had independently obtained wide recognition and was increasing in value—art critic Dan Cameron has called him “one of the most potent voices of his generation”—we were unable to demonstrate that the controversy had caused him financial damages. As a result, the court ordered Wildmon to pay David one dollar in nominal damages. David promptly incorporated the dollar in an artwork inspired by the controversy. Two years later, David died.

Around the same time, the Corcoran closed a show of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs because of pressure from social conservatives, and the NEA revoked funding to four performance artists—Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller—after conservative columnist Robert Novak blasted the endowment for using public money to fund gay and sexually-explicit artwork. We sued the NEA over its denial of funding, and after a court rejected its motion to dismiss the case, the NEA agreed to pay the artists the amount of their grants.

In one sense, David Wojnarowicz and the NEA Four won. The fact that the National Portrait Gallery has now dedicated a major exhibition focused on sexual difference and marginalization in American portraiture is also surely a victory. We live in more tolerant times, in which gay characters are frequently the stars of popular films like The Kids Are All Right and television series like “Modern Family” and “Glee,” and young people feel more comfortable acknowledging their sexual identities to their parents and friends. The military wants to end “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and several state courts have legalized gay marriage and civil unions.

But the battle is far from over, as the Smithsonian’s recent cowardly action, California’s continuing struggle over gay marriage, and Congress’s refusal to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” make clear. Polls consistently show that the next generation’s leaders have grown to accept homosexuality, but the vestiges of the hate, fear, and prejudice that David Wojnarowicz felt so deeply and objected to so eloquently are still a part of American culture—then as now fanned by fundamentalist religious fervor.

And from the standpoint of publicly funded art, the censors have won. Congress’s response to the “culture wars” was to require the NEA to “take into consideration general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public” in making arts funding decisions. The Supreme Court upheld that requirement. Public arts institutions learned that political controversy could jeopardize their financial support, and publicly funded arts have never been the same. When the National Portrait Gallery put on “Hide/Seek,” it made sure to finance it only with private donations, undoubtedly recognizing that it might stir protest. The show’s private funding was insufficient, however, to steel the Smithsonian when it faced criticism. (And now one of the largest private funders, the Andy Warhol Foundation, has threatened to cut off its financial support because the museum caved to pressure).

Advertisement

But while the recent censorship of Wojnarowicz’s work recalls what happened in the early 1990s, the differences are also instructive. When the Corcoran closed the Mapplethorpe show and the NEA revoked Karen Finley’s funding, widespread public outcry followed. The Smithsonian’s decision to remove Wojnarowicz’s video, by contrast, has attracted comparatively little attention. We have come to expect timidity in public arts institutions. In some sense, the surprise is not that the Smithsonian removed the video, but that it put on “Hide/Seek” in the first place.

The muted public response to the current controversy points in two different directions. On the one hand, homosexual self-expression is substantially more accepted today than it was twenty years ago. David would, I think, be surprised and gratified by the changes wrought in American culture. Those changes have come about largely because David and others like him have been willing to speak out from the margins of our society, even as they found themselves hated by people they did not know simply because they were brave enough to express their sexual identities. On the other hand, the fundamentalist censorial strain remains a profound force in American society, reflected today in the populist and often intolerant undertones of the religious right and the Tea Party. And one thing has remained a disappointing constant—public institutions’ willingness to cave on issues of public controversy. Like so many other wars, the culture wars of the 1980s have left their traces on America’s character.

Owing to an editorial error, an earlier version of this post stated that William Donoghue had demanded that the Smithsonian take down the piece by Wojnarowicz. This was not the case.