Tibor de Nagy, the iconic midtown gallery, has been celebrating its sixtieth anniversary with a show that doesn’t so much trace its history as distill its early essence. “Painters & Poets” includes drawings, chapbooks, letters and well-known paintings that emerged from the fantastic collaborations between Frank O’Hara and Larry Rivers, O’Hara and Joe Brainard, Brainard and John Ashbery, James Schuyler and Grace Hartigan, among many others. The energy of the poets drove those projects, yet often the painters made them sit still and keep their mouths shut, as we see in the many striking portraits in this show of poets reading, writing, sitting there, spacing out, in every phase of dress and undress. Other times, they inspired one another to produce works—like Hartigan’s series of paintings made in response to O’Hara’s poem “Oranges”—that drew from their complementary strengths. “The strangeness of the collaborative situation,” wrote Kenneth Koch, another mainstay of the group, “might lead them to the unknown, or at least to some dazzling insights at which they could never have arrived consciously or alone.”

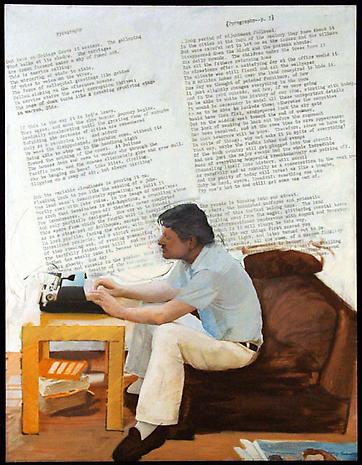

The body of Frank O’Hara—the broken nose, the bouncy gait, the jaunty posture—was a special fixation, almost the Mont Sainte-Victoire of this coterie. Rivers especially ranged across media to figure out how O’Hara’s personal dynamism might be captured in static form; his plaster bust of O’Hara, its single blue eyeball suggesting the effaced and white-washed grandeur of the classical past, is one of the show’s highlights. The two friends also famously worked together on the same surface, jointly creating a series of lithographs called “Stones” that combined searching, fragmentary drawings by Rivers alongside improvisatory verse by O’Hara. This wasn’t a case of finding “some painter and some poet who would work together,” Rivers said, but a special circumstance of “two men who really knew each other’s work and life backwards, which means to include all the absurdity and civilization a lively mind sees in friendship and art.”

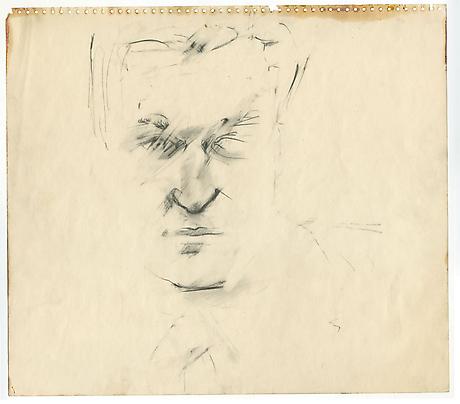

There are many images of Ashbery too, notably a Rivers sketch of him furrowing his brow, that suggest a different problem from the one O’Hara presented: Ashbery, by turns daffy and mournful, is the great inscrutable mind of this period and one of the richest models of pure interiority in American letters. To sketch him furrowing his brow is to hint not only at the buzzing life it contains, but at the limitations of pictorial representation of mental life.

It would be wonderful if the show ushered in a new era in which painters seek out poets and—seemingly mesmerized by the sight of them sitting around—paint them in states of repose. But that won’t happen, any more than it will bring back the era of cheap New York apartments. (Several of these artists and poets, at one time or another, were neighbors on West 21st Street; one wonders, as the critic Douglas Crase asks in his terrific catalog essay, “if artistic communities initiated by physical proximity can ever reoccur.”) The moment so succinctly conjured by this show is gone forever—though two of its stars, Ashbery and Jane Freilicher, are still around, working away.

Crase calls it “a vanguard of friends,” and quotes Kenneth Koch’s assessment of the gallery—with its parties, openings, theatrical productions, and experimental book imprint that published hybrid works of poetry and art—as a place for people to be “envious and emulous of each other and inspiring each other and collaborating.” To the unexamined idea that art should be “universal,” this show offers a reproof: you had to be there. But far from feeling excluded, what we feel, instead, is the special poignancy of a moment’s having existed in time, and having missed it. And that is a universal emotion.

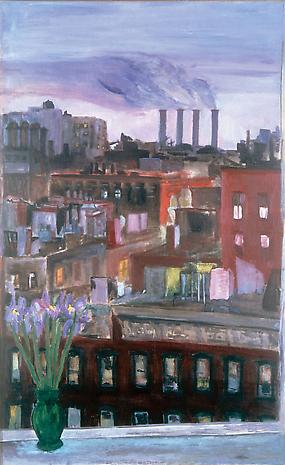

Every one of these artists and poets sought, in their various modes of art, the transfigured but still recognizable real, the recording of perceptions and banal facts almost for their own sakes, with as little metaphysical inflation as possible. You see it in a wonderful canvas by Freilicher called “Early New York Evening”: it’s a view out the window, the exact size and shape of a window, of rooftops and smokestacks across the Hudson. The painting allegorizes itself, its own small stay against unstransformed reality, with a vase of irises Freilicher paints on the sliver of sill she includes in the frame. This body of work, in its day, stood for the dailiness of beauty. In retrospect, the terms shift subtly, and it stands instead for the beauty of dailiness

Advertisement

This was one of those moments in the arts when the mellow transcription of what we experience as real had an important job to do. Partly its job was to ironize grand-format abstraction and its vainglorious purveyors that had dominated the art scene of 1950s New York. The cowboy masculinity of their slightly older painter-peers (Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning in particular) and their dour poet elders (I mean mainly Eliot and Yeats—Stevens and Auden were beloved by this group) lent itself to big claims (this is the era of the angsty individual artist flinging his soul against the universe’s nothingness) and also to tart parody.

This was, remember, the first generation of American poets and painters to have studied their media in classes like the ones colleges still teach: those surveys of art history and English poetry, which have become a recognizable cultural symbol for boredom. There, the acts of daydreaming, writing notes, glancing furtively at attractive classmates, and so on, are at least as important as the lecture. Ashbery’s long poems, in particular, always track their own acts of drifting and returning attention (“The balloon pops/The attention turns dully away,” he writes, in “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”). His poetry could be seen in fact as one elaborate daydream, a lecture about great works of art or masterworks of poetry droning on in the background (in his poems, the curtains of cognition sometimes part, and we hear snippets of those otherwise occluded lectures).

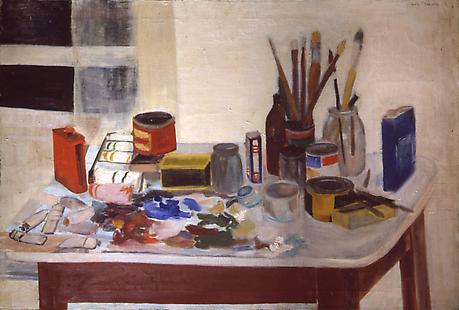

Pollock had been lionized in 1949 by Life magazine; by 1951, his famous technique was something you could see practiced in art classes at the YMCA. Aspiring artists were dripping, slashing, hurling, spilling, and dragging paint all across the country (though this is probably slightly before the era of Pollock-style crafts projects for fourth graders). This is why the little daub of white paint in Jane Frielicher’s quietly brilliant canvas, The Painting Table, strikes me as one of the great daubs of paint in American art.

Everything in this show requires close-up scrutiny of multi-faceted images, canvases with lots of small dramas and scattered events. This in itself is an aesthetic intervention at a moment when big canvases that made a single impression—think of Mark Rothko—were the rule and the vogue. But the Freilicher painting, which is only about 26 by 40 inches in dimension, really depends on getting up so close that the one raised glob in its lower right quadrant, near the edge of the table it depicts, stands out. It looks as though she’s just squeezed the paint directly from the tube, the way Pollock sometimes did (an art historian friend of mine assures me there is no technical term for this method, and opines that “that’s why descriptions of Pollock are so pseudo-poetic”).

But the meaning here of paint-as-paint could not be more different than in Pollock’s ejaculations. Freilicher’s is a painting, after all, of a painting table. And that daub of white paint represents—well, it represents a daub of white paint, waiting on its palette for the tip of a brush. Which makes this perfectly representational picture in its weird way abstract, or at least what people often mean by abstract: a painting of painting, a closed loop that refuses external reference much more successfully than Pollock’s or de Kooning’s paintings, which, Rorschach-like, always suggest “real” things beyond themselves—landscapes, cityscapes, people.

The great things in this show—Freilicher’s painting, the weird doodles in colored pencil on looseleaf by Dwight Ripley, Rivers’s astounding sculpted bust of O’Hara, the Porter double portrait of Schuyler and Ashbery sitting uncomfortably on a sofa with Matisse-like blocky print upholstery—are seen as a footnote in the grand narrative of art that passes from Pollock and de Kooning to Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg: Peter Schjeldahl, in a recent New Yorker piece, suggested as much. People tend to think it was the poets, with their more radical styles, drawing from the rudiments of Modernism but adding a special element of human sympathy, who were really onto something. I love the poets immoderately. But the paintings make you think more daring thoughts: that painting, by bursting its seams, also killed itself off prematurely; that minor-key affects like friendliness, boredom, low-level appreciation, passing affection, tidiness as opposed to orderliness, craft as opposed to genius, delineate a zone for all artistic media that remains still uncharted. There’s no way out of progress, but Tibor, the little bubble of beauty on Madison Avenue and 55th Street, is still there and still thriving.

Advertisement

“Painters & Poets” is on view at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery through March 5.