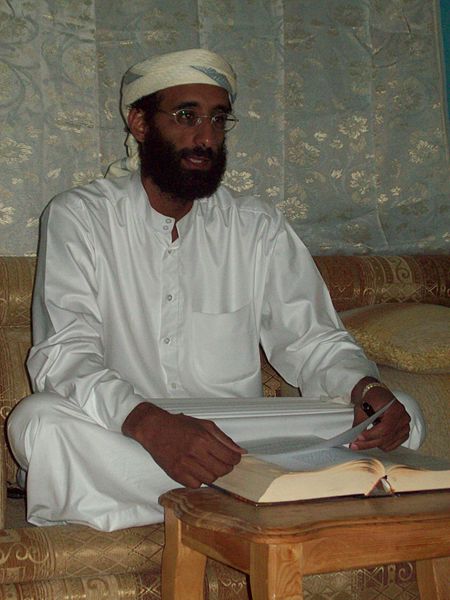

Sunday’s New York Times reported that the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel has produced a fifty-page legal memo that purportedly authorized President Obama to order the killing of a US citizen, Anwar al-Awlaki, without a trial. Last month, the US carried out that order with a drone strike in Yemen that killed al-Awlaki and another US citizen traveling with him. The strike was front-page news, and apparently was undertaken with the approval of Yemen authorities, yet as it was a “covert operation,” the Obama administration has declined even to acknowledge that it ordered the killing.

So now we know that there is a secret memo that authorized a secret killing of a US citizen—and both the memo and the killing remain officially “secret” despite having been reported on the front page of The New York Times. Whatever one thinks about the merits of presidents ordering that citizens be killed by remote-controlled missiles, surely there is something fundamentally wrong with a democracy that allows its leader to do so in “secret,” without even demanding that he defend his actions in public.

As I have argued here previously, it is not necessarily illegal, in wartime, to kill a citizen without a trial. Lincoln’s Union Army did it repeatedly, of course, during the Civil War. If US soldiers had confronted al-Awlaki carrying a gun on an Afghan battlefield, the laws of war would permit them to shoot him on the spot. No one could credibly maintain that they would have to wait till a jury of his peers convicted him and the Supreme Court denied review.

But al-Awlaki was not on the battlefield. He was in Yemen. And he was not even alleged to be a part of al-Qaeda or the Taliban, the two entities against whom Congress authorized the President to use military force in a resolution passed one week after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, which continues to provide the legal basis for the war on al-Qaeda and the conflict in Afghanistan. Al-Awlaki was alleged to be a leader of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), an organization in Yemen founded long after the September 11 attacks. He had never been tried, much less convicted, for any terrorist crime. He corresponded by email with Nidal Hasan six months before Hasan shot and killed 13 men at Fort Hood in November 2009, and was allegedly involved in planning the foiled airliner bombing near Detroit on Christmas Day 2009. But he was not charged in either crime. Neither attack, moreover, was carried out by al-Qaeda or the Taliban. Are unofficial “allegations” of encouragement of or involvement in terrorism enough to authorize the secret execution of a citizen?

The New York Times reports that the memo concluded that al-Awlaki could be killed without trial because he was the leader of AQAP, which it deemed a “co-belligerent,” effectively fighting alongside al-Qaeda itself; because he posed an imminent threat to the United States; and because killing was a permissible option if capturing him in Yemen was deemed “not feasible.” If all of these conditions were in fact met, al-Awlaki’s targeted killing may well have been justified as an incident of war.

But none of these assertions has been tested in any forum, and at a minimum there are serious questions about the latter two. What is the “imminent” threat that al-Awlaki posed? No one has claimed that he was involved in planning an imminent terrorist attack on the United States when the drone missile struck. The memo reportedly argued that the “imminence” criterion could be satisfied by a finding that he was the leader of a group that sought to attack the United States whenever it could, even if he was involved in no such attacks at the time he was killed. But that surely stretches the imminence requirement beyond recognition, virtually to the point of abandoning it altogether.

And why was it “not feasible” to capture al-Awlaki alive? The Yemen authorities reportedly permitted the drone attack. We are apparently working with them very closely, and may well have special operations forces on the ground there. Even in the case of the raid on Bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan, administration officials considered the possibility of capture instead of assassination. Was it really not possible to try to capture al-Awlaki? What does it take to show that such an option is not feasible?

Answering these questions is critical to assessing the legality of al-Awlaki’s killing—and its implications for continuing drone killings of suspected terrorists in many parts of the world. But because the Obama administration will neither acknowledge that it killed al-Awlaki, nor make public the legal case for doing so, the questions remain unanswered.

As American citizens we have a right to know when our own government believes it may execute us without a trial. In a democracy the state’s power to take the lives of its own citizens must be subject to democratic deliberation and debate. War of course necessarily involves killing, but it is essential that at a minimum, the lines defining the state’s power to kill its own are clearly stated, and public—particularly when the definition of the enemy and the lines demarcating war and peace are as murky as they are in the current conflict. Leaked accounts to The New York Times are no substitute for legal or democratic process. As long as the Obama administration insists on the power to kill the people it was elected to represent—and to do so in secret, on the basis of secret legal memos—can we really claim that we live in a democracy?

Advertisement