There was reason to expect some personal revelations when the musician and writer Patti Smith took the stage at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on a Friday evening in early December. She was there to talk about Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer and indefatigable promoter of modern art whom O’Keeffe married in 1924. An exhibition upstairs in the Tisch Galleries—showcasing the works of art that O’Keeffe had selected from Stieglitz’s private collection and given to the Met in 1949, including some of his erotic photographic portraits of O’Keeffe herself—was the immediate occasion for Smith’s appearance, along with the publication of the first volume of letters by O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, which Smith carried onto the stage like a bible, festooned with yellow Post-it notes. Smith was accompanied, for an evening of songs, readings, and ruminations, by her daughter, the pianist Jesse Paris Smith, and by her longtime band-member Lenny Kaye, the guitarist and rock archivist.

But readers of Smith’s memoir Just Kids, which won the National Book Award last year, knew that she had been thinking about O’Keeffe and Stieglitz for a very long time. There’s a turning point about two-thirds of the way into the book when Smith and her friend and lover Robert Mapplethorpe are invited to a private viewing of the Met’s photography collection by the curator John McKendry.

At the time, Smith was, as she said, “at a crossroads” in her life, trying to figure out if her future was in music or poetry, and what part Mapplethorpe, who had taken many photographs of her but was spending more of his time in gay circles, might play in it.

John saved the most breathtaking images for last. One by one, he shared photographs forbidden to the public, including Stieglitz’s exquisite nudes of Georgia O’Keeffe. Taken at the height of their relationship, they revealed in the intimacy a mutual intelligence and O’Keeffe’s masculine beauty. As Robert concentrated on technical aspects, I focused on Georgia O’Keeffe as she related to Stieglitz, without artifice. Robert was concerned with how to make the photograph, and I with how to be the photograph.

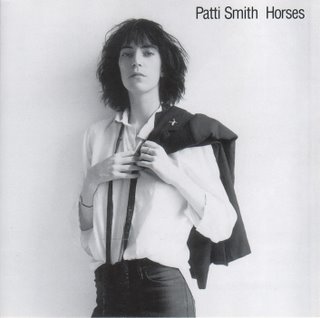

It was 1971, four years before Smith’s debut album, “Horses,” with Mapplethorpe’s famous cover photograph of her. In the photograph, she wears men’s dress clothes with a jacket slung over her back “Frank Sinatra style,” as she put it, emphasizing, perhaps, her own masculine beauty.

One might have expected that Smith, on stage at the Met, would elaborate on the comparison of the two couples, and what it might mean to “be the photograph,” as model and muse. O’Keeffe, as a young aspiring artist, had come east in 1918 from a grim teaching job in rural Texas, and had formed a partnership with a photographer who took hundreds of photographs of her. Smith, born in Chicago and raised in New Jersey, had done pretty much the same thing fifty years later, dropping out of college and working in a factory before she and Mapplethorpe took up residence and began their artistic life together, dreaming of Rimbaud and William Blake, in the Chelsea Hotel.

It’s a Dream

The first surprise of the evening was that Smith, between songs, said nothing whatsoever about Mapplethorpe, who died of AIDS in 1989. The second was that she said so little about Georgia O’Keeffe, apart from reading a couple of letters, singing a moving rendition of “Georgia on My Mind,” and reciting a poem she herself had written around 1973, “when I was my daughter’s age,” as she ruefully noted, with hammering lines like these:

georgia o’keeffe

all life still

cow skull

bull skull

no bull shit

Georgia on My Mind

Instead, most of the evening was devoted to Alfred Stieglitz. Smith read aloud from many of Stieglitz’s letters, especially from the year 1918, “a vintage year for Alfred,” according to Smith, when his relations with O’Keeffe were at their most innocently ecstatic, before their temperamental differences had emerged clearly. Two years earlier, a friend had brought a pile of O’Keeffe’s daringly abstract charcoal drawings to Stieglitz’s gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue, and he had been astonished by their confident audacity.

This is where the surprise came for me. I had the read the volume of their correspondence, all 800 pages of it, and found myself impatient with Stieglitz’s voice, which I found pompous, self-indulgent, condescending, and repetitious. But Patti Smith found an unexpected lyricism in Stieglitz’s declamatory repetitions, not unlike the incantatory and intimate lyrics of her own songs. She was also able to convey, with the tilt of her head and the tone of her voice, what it might have been like to receive these letters—to be, as she expressed it in Just Kids, the photograph.

Advertisement

With her daughter’s ruminative accompaniment on the piano, reminiscent of Keith Jarrett with a touch of Debussy and Satie, Smith began reading, in a hushed voice, a Stieglitz letter from May 26, 1918:

What do I want from you?—

—It’s hardly six—morning—Sunday—cool—clear—the window wide open—I propped up in bed—feeling rather sick at heart—yet—still dreaming—having thought all night—sleeping impossible.

What do I want from you?

Your letter—I sent you a letter finished at the Manhattan Hotel—I went away & ordered something to eat—I re-read your letter—read it really for the first time…

There it stood in large blazing letters—Wherever I looked: “What do I want from her”—And there was no answer.—Do I want anything from her that she hasn’t already given me over & over again—from the first moment I saw the drawings.

It was easy to imagine a song by Patti Smith with the chorus “What do I want from you?” It might be something like “Blue Poles,” her beautiful Dust Bowl ballad, inspired by a ravishing Jackson Pollock painting of 1952, about traveling west, which she sang with an aching yearning, and seemed choked up after the last chorus of “Blue poles infinitely winding, as I write, as I write.” The song reminded me of O’Keeffe’s gorgeous watercolor upstairs, Blue Lines (1916), which Stieglitz considered a portrait of the two of them—two blue lines, one straight and one bent, side by side.

Blue Poles

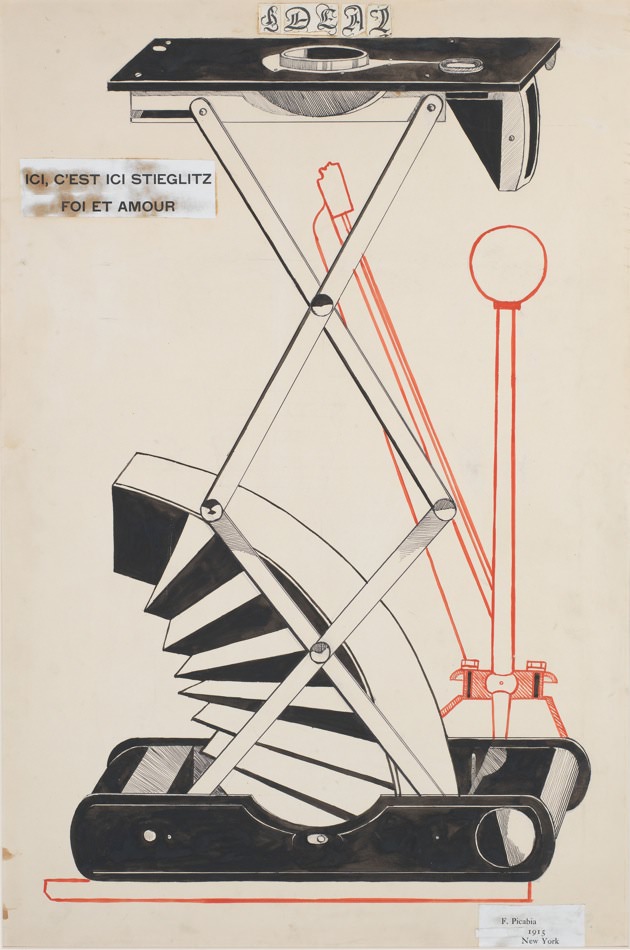

A less harmonious portrait of the couple is conveyed by other images from the Met exhibition, however, such as Francis Picabia’s 1915 caricature of Stieglitz at fifty as a stalled piece of machinery, part collapsed camera and part gearshift jammed in park. A few rooms away we see Stieglitz’s photograph of O’Keeffe in one of the cars he hated, “Hungry dreaming going west,” as Patti Smith sang in “Blue Poles,” away from New York and Stieglitz.

Smith read another of Stieglitz’s letters from 1918, ending with the lines “And I love Life and fear not Death—Because I’ve lived—But never as now—these days! Good Night—I’m with you.” With the final phrase, Lenny Kaye laid down the opening chords of “Because the Night,” and the sellout crowd stood up and cheered.

Because the Night

All songs performed by Patti Smith, Jesse Paris Smith, and Lenny Kaye and are reproduced here courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum; “It’s a Dream” is written by Neil Young; “Georgia on My Mind” is by Hoagy Carmichael and Stuart Gorrell.