Hanukkah commemorates persistence against overwhelming odds, when Jewish rebels in Judea defeated their Hellenic overlords and oil lamps meant to last a single day miraculously burned eight times as long. Five years ago I heard of what seemed another miracle. Despite having been nearly stamped out by the Nazis six decades earlier, the spirit of Jewish life in Poland had been kindled again in Kraków, near the farmlands where my family had lived for perhaps nine centuries.

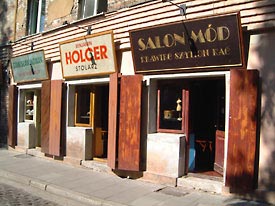

Cafés, I was told, served jellied carp with raisins. Klezmer tunes bounced down the cobbled streets. Prewar shop signs had reappeared, flanking a bustling square as if its Jews had never left. The cooks and klezmorim, I later learned, were nearly all non-Jews, the crowds made up of tourists, the façades only that. Auschwitz, a mere hour away, remained a brutal warning against rosy nostalgia or frivolity. Still, I needed to see all this for myself. I went.

The Festival of Jewish Culture takes place each midsummer in Kraków’s former Jewish quarter. It began at the close of the communist period as a low-key affair organized by a non-Jewish Krakovite haunted by his city’s history and leaders of Warsaw’s “Flying Jewish University”—a sort of underground Hebrew school. Now it runs for over a week and draws tens of thousands of visitors—mostly non-Jewish Poles, Germans, and other Europeans. (There are about 5,000 to 30,000 Jews in Poland today, depending on how you count.) Desecrated cemeteries and synagogues have been restored and abandoned townhouses turned into shops, hotels, and restaurants, some with Jewish themes. The overall effect may recall Disney’s Main Street USA, though the festival itself is, for the most part, deeply earnest and respectful. The program combines entertainment by musicians and theater troupes, Jewish and Gentile, working to preserve the Jewish legacy, with scholarly lectures on Europe’s Jewish past, hora dance lessons, and discussions between Jews and non-Jews about the Holocaust and continuing anti-Semitism.

My trips to the Kraków festival led me to other cities in Europe and Asia whose suppressed Jewish histories are now being recovered—and reenacted—in fascinating ways: Łódź, Berlin, Vilnius, Lviv, and elsewhere. Perhaps the most bizarre is Birobidzhan, in far-eastern Russia, near China, established by Stalin in the 1930s as a relocation colony for Jews unwanted in Ukraine. Of the 40,000 Jews who were settled there, most intermarried, assimilated, or emigrated. There are few “full” Jews remaining, but sixteen percent of the city’s current population of 75,000 claim some degree of Jewish ancestry, and the city has made a major effort to showcase its heritage. Birobidzhan’s own Jewish culture festival, which takes place every other September, has grown from a local talent show into a grand, Hollywood-style affair, with glitzy sets and imported entertainers. Few visitors from afar attend, yet aspirations remain high—plans are in the works to build a full-scale “Jewish town” based on Seoul’s Korean Folk Village. The city council has ordered restaurants to revive old Jewish dishes: this year’s festival involved a sixty-six-foot gefilte fish aimed at a world record to put this remote, somewhat bleak swamp-plane town on the map.

But other attempts at reviving Birobidzhan’s Jewish culture are more serious. Yiddish—once an official language of the region, the only place in history where this was ever so—appears on street signs and in the local paper, and is taught in schools. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, 150 Yiddish teachers have been trained. Community groups stage Yiddish plays and songfests. TV and radio shows feature Jewish themes. Many who take part have no Jewish background, but treat the city’s Jewish past as a civic legacy it is their duty to uphold. And Jews are admired for what are regarded as laudable values: education, self-discipline, and financial smarts. After Russia’s long history of persecution, Birobidzhan’s Judeophilia, however reliant on stereotypes, may be something of a positive development.

The Jewish festival in Hervás, Spain, which I attended in July, is a different case. Hervás is a mountain village some hours’ drive through scrubby desert from Madrid. Its festival technically honors conversos, or Jews forced to convert during the Inquisition. While Hervás had Jewish inhabitants—forty Jews, or possibly Jewish families, are listed in a census from 1492—cohesive, flourishing communities of Jews lived in larger towns several miles away. And the well-preserved medieval neighborhood registered as the “Jewish Quarter” was no more Jewish, scholars maintain, than any other in Hervás. The quarter, they say, is really just a fantasy devised to attract tourist income to a town with stunning architecture and views but little employment.

Advertisement

The festival features a play—a fluffy melodrama of doomed love between a Jewish girl and Catholic boy slain by spurned lovers from both sides. A spectacular mash-up of medieval pageant, commedia dell’arte, Fiddler on the Roof, West Side Story, and soap-opera télénovela, the show is performed on the Hervás riverbank in the middle of the night. It involves a cast of eighty, including acrobats, fire jugglers, scores of children, a dog, a donkey, and a horse. (A tragedy about Spain’s Jewish past by a Jewish author in Madrid, mounted the first year of the festival, was hugely reworked and then scrapped as insufficiently festive.) The audience—teens in bleachers, elders in folding chairs, toddlers surreally placid given the hour crawling in fresh-mown hay—chats throughout, pointing at friends in the cast. The event has the aura of a county fair.

By day, villagers attired as Jews, loosely imagined—Moroccan djellabas, hippie skirts, babushka scarves—hold what’s billed as a “Jewish market” (what makes it Jewish, evidently, is the notion common in Spain that Jews excel at selling things). Among scheduled activities, only one had much to do with Jewish history: a walking tour sponsored by a progressive folksong troupe from a larger city in the region relating the events of the Inquisition. Shoppers looked up, startled and transfixed, but when the tour moved on the market resumed its holiday air.

The commercial aspects of Hervás’s festival—funded by the village’s chamber of commerce as a boon to local business—are hardly unique. Birobidzhan’s cultural renaissance, has, similarly, garnered it development grants from Moscow; while on the fringes of the Kraków festival, stands sell hook-nosed “Jew” figurines. Yet much more is at stake in both places than profit. In Kraków, with its rich, traumatic history, the festival is an attempt to confront the still relatively fresh loss of what was once the world’s largest Jewish population, as well as the question of Polish complicity with Nazis in the war, communist suppression of Holocaust history, and continuing European intolerance; it’s also a chance for Poles to reflect on their country’s future as a conservative, culturally monolithic nation in a changing, diversifying Europe. Birobizhan’s Jewish cultural revival appears primarily to enliven an isolated, poor, rather bleak place unremarkable but for its unique history. Despite some silliness and confusion, the more sober efforts to teach Yiddish and Jewish history ensure that important legacies are preserved. And perhaps even theme-park-style memorialization is more salutary than the more common case in places from which vital cultures have more or less vanished: sheer oblivion.

In Hervas, the evocation of a Jewish past is so perfunctory and historically fanciful as to border on the offensive. Stars of David adorn street signs, window grates, and even, for no clear reason, the church. There is a Judería Tavern and a Hotel Sinagoga: the former, on inspection, specializing in ham, the latter indistinguishable from a Holiday Inn. On arrival, I was amused by the kitsch; but by my last day, I felt vaguely sick. The empty symbolism cruelly underscored all that Europe has lost.