The spectacle of the Republicans, like teenagers longing to be invited to the prom, floundering about in search of more popularity with American voters, would be comical if it didn’t present the sad picture of a once great and proud party—the party of Lincoln and Eisenhower—working its way into near irrelevance. The Republican Party is having its own form of PTSD. According to one of the most respected party elders the Republicans firmly believed that the voters would reject Barack Obama for a second term and deliver the Senate back into their hands. Wishful thinking combined with erroneous polling assumptions left them totally unprepared for the thumping loss they sustained and they are still in something of a state of shock. “They’re still close in time to that event,” the party elder said. “You need to keep that in mind. Right now they’re groping around in a dark room.”

As the Republicans search for a new and more electable identity they have a fundamental problem. Ever since they took their first major right turn in 1964, they have made a series of bargains in order to strengthen their ranks: the Christian right, the Southern strategy, which validated racism as party policy, the Sagebrush Rebellion, which represented big ranching and farming interests as well as the mining industry, the Club for Growth, a highly conservative organization with a lot of money to pour into primaries to defeat more centrist incumbents. However successful momentarily, this series of deals ultimately cost the Republicans broad national appeal and flexibility.

The emergence beginning in 2010 of the Tea Party as a force in Congress—part grass roots, part developed and exploited from Washington—pushed the Republican Party still further to the right. Conservatives took control of a large number of states and had a significant impact on national policy, and for the first time, there was a sizeable number of House members who despised government and had run on the explicit promise never to compromise.

Joe Scarborough, the former Republican Florida Congressman turned philosopher at the breakfast table, frequently laments on his weekday morning show on MSNBC the Republican Party’s narrowing of its base and its outlook, and its consequent loss of appeal to the country at large. Repeatedly, Scarborough has anguished over the facts that the Republicans have lost the popular vote in five out of the last six presidential elections, blown two opportunities to retake the Senate, and even lost the popular vote for the House in 2012, managing to hold onto a majority of seats only as a result of gerrymandering in Republican-controlled states.

In a recent speech to a conservative group, Scarborough observed,

I think the debate has been stifled. It has been stifled because we have created this conservative groupthink over thirty years that has become more and more narrow. A conservative groupthink that would allow all of our primary presidential candidates being asked if they would take a 10-to-1 deal on spending cuts to taxes, and everybody’s afraid to talk. Everybody’s afraid to talk about regulation.

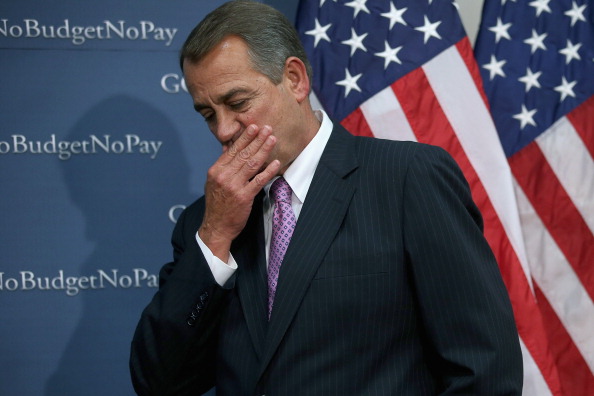

The changed nature of the Republican party hasn’t made for a happy situation for House Speaker John Boehner, a deal-maker of the old school whose idea of being a legislator is to work out legislative solutions. At a party retreat in Williamsburg, Virginia in mid-January, Boehner, aware of the corner his troops were heading into, along with Paul Ryan, who has enjoyed the backing of the Tea Party members, set out to instill a bit of pragmatism into the Tea Party caucus—the leaders warning the Tea Party types that they were pushing the party into the fringe and playing into Obama’s hands. But in exchange for Tea Party members agreeing to a three-month extension of the debt-ceiling, postponing the crisis until mid-May, the leadership had to agree to do the seemingly impossible—balance the budget in ten years, presumably without using additional tax revenues. This would force the House Republicans to take a nihilistic approach to government that won’t serve their electoral purposes.

The recent attempts of other Republican leaders to put a prettier face on their party have been notable for the fact that they are still dealing in cosmetics. Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal got attention, which he surely expected, with a line in a much touted recent speech saying that the Republicans should stop being “the stupid party,” should appear less coddling of the wealthy—and then he proposed that Louisiana replace the income tax with a sales tax, which is of course more regressive. (The sales tax policy is much in vogue with Republican governors, in part because it is produced by ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council funded by large corporations and the Koch brothers, who helped many of them get elected.)

Advertisement

And House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, not regarded as the cuddliest of congressmen, the day before he was to give a highly promoted speech to the conservative American Enterprise Institute, fell back on a device long used by the party’s presidential candidates, from Richard Nixon and his newfound buddy Sammy Davis Jr. to Mitt Romney and his awkward posing for pictures with black schoolchildren. Cantor dropped by a private school for children in a low-income part of Washington, where, as the cameras clicked away, he held a small black child in his arms and played with plastic dinosaurs—a symbol? In his effort to give his party a more human face Cantor proposed vouchers for education and the repeal of a tax on medical devices that the industry has been trying to excise from the new health care law. Like Jindal, Cantor proposed nothing that contradicted established Republican dogma.

With very big money coming in from strictly conservative ideologues (the Koch brothers are but one example) along with specific policy instructions, and with the conservative think tanks moving further to the right, there has remained little reward and no incubator of consequence for moderate Republican inclinations. Indeed, moderates and even a conservative or two were knocked off in primaries on grounds of impurities, such as cooperating at all with the president.

After Dick Lugar, the esteemed longtime Indiana senator with internationalist interests but a conventional conservative domestic record, was defeated in a primary by Richard Mourdock, a candidate with strong support from the Tea Party and the Club for Growth, Senate Republicans fretted aloud about the possibility of being “Lugared.” In Kentucky, for example, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell may well be challenged for reelection by a candidate from the right, as well as by Ashley Judd running as a Democrat. That Mourdock, as dimwitted as he was talkative about matters of rape, lost what should have been a safe Republican Senate seat was a repeat of a pattern that began in 2010, of the Tea Party getting behind candidates who turned out to be embarrassments.

The impact of the Tea Party outruns its numbers. While forty-nine House members currently count themselves as belonging to the Tea Party Caucus, at least sixty-six have been affiliated with it at some point; and there are others who share the Tea Party philosophy but see joining a formal caucus as antithetical to their concept of being apolitical, and still more who count themselves as highly conservative and, out of self-protection, vote the Tea Party line. These people ran against the “party establishment,” charging that it had sold out conservative principles by voting for the stimulus, TARP, and the auto bailout. They acquired great force by their perfervid opposition to the health care law, whether or not they understood it. They were also used as pawns by larger interests opposed to the bill and who fed their paranoia of a government take over of health care.

But politics is predicated on the idea that its practitioners will work out their differences. This was a revolutionary change—no president of either party had been confronted with such an obdurate opposition. “Compromise” had never before been a term of obloquy. Regularly frustrated by these absolutists and those too frightened of the movement to challenge them, Boehner has less control over his flock than any Republican Speaker in memory. It’s not that he’s lacking the political skills; the Tea Party members and the school of fish that follows them won’t vote with Boehner out of party loyalty because they simply don’t owe him anything. They got to Congress with strong financial support from powerful interests and they have their own constituencies.

While Democrats might enjoy the spectacle of a dejected and squabbling Republican party, this development isn’t really in their interest. Or in the country’s. The point of winning is to govern; and one can govern through one’s own party plus a few renegades, or by forming more broad-based coalitions behind proposals that are acceptable to most of the country. The country needs a healthy two-party system, one that can forge widely accepted bipartisan agreements on the great issues of the day, as occurred over the civil rights laws of 1964 and 1965. By contrast the fight over the 2010 passage of President Obama’s jewel in the crown, the health care law, was so bitter that it has carried over into its implementation.

More than half the governors, including all but one of the nation’s Republican statehouses, have refused to set up state exchanges through which consumers are supposed to be able to shop for competing insurance plans. FreedomWorks, the most powerful national Tea Party organization, has waged a national crusade to “Block Obamacare” by rejecting the exchanges. The joke is that if a state refuses to set up an exchange the federal government will come in and do it. (Six Republican governors have accepted the Medicaid expansion in the health care law because the offer was too good to turn down.) Another tactic the Republicans have used to fight laws on the books is to block the appointments of the president’s nominees to administer them.

Advertisement

One substantive matter on which leaders of the two parties agree is immigration reform—not just because it’s the right and urgent thing to do but because it’s in their interest. The Republicans panicked about the huge electoral advantage the president got in 2012 from Hispanic voters, whom he carried 71 percent to 29 percent, and who provided the margin of victory in some key states. In their debates in the primaries last year most of the Republican candidates played to the strong anti-immigrant streak that dwells within the party’s rank and file. And at election time—as in the case of other groups the Republicans had baldly tried to keep from the polls in order to depress the Democratic vote—these efforts backfired, and Hispanics turned out in unprecedented numbers.

But while immigration reform may be seen as the next great civil rights advance the actual hammering out of a bipartisan bill is likely to prove extremely difficult. Such bills have foundered before on fierce regional and partisan differences. And as in the case of other minorities, more than one issue is at stake. As long as the Republicans push for “smaller government”—a euphemism for cutting domestic programs such as education at all levels as well as food stamps, unemployment benefits and Medicaid and of course the tax rates—their appeal to groups they’ve been losing will remain limited. The Republicans are in a deep hole and it’s not foregone that even if an immigration law is passed Hispanics will turn to them in droves.

Immigration isn’t a newfound legislative problem for the Republicans: a recent proposal hammered out by a bipartisan group of eight senators (wretchedly referred to as a “gang”) strongly resembles the fairly enlightened program of naturalization and eventual citizenship proposed by George W. Bush. (The Bush bill was denounced by members of his own party and failed to gain the support of Democrats who weren’t keen to give him a legislative triumph on immigration.) The proposal is looked upon favorably by Obama—though he knows that if he explicitly supports it (or any other bill), it will automatically be opposed by the Republicans. It has come to that.

So now the Republican Party—having become a refuge for better-off and older white voters, especially male, a harbor for millions who could not bear the idea of the presidential office being occupied by a black man, a party whose presidential candidates have not shied away from making racist appeals—is confronted with a population that is inexorably moving toward a nonwhite majority. While the cross-over is not estimated to occur until 2043, each new group of Americans who reach voting age will increasingly reflect the trend. The Republicans have a demographic crisis that from long habit they’re ill equipped to cope with.

The immigration issue is also caught up in presidential politics. Florida freshman senator Marco Rubio’s presidential ambitions have been obvious as he has rocketed to fame within a few months of hitting Washington. Rubio’s eagerness to have a starring role on immigration has been welcomed by Republican leaders as a sign of their newfound sympathy for Hispanics, but he will have to negotiate a tricky course on the issue of border security. He has promised conservatives that he will insist that southwestern governors be given a veto on whether the border between the US and Mexico is sufficiently impenetrable before other immigration reforms can go forward. But Charles Schumer of New York, speaking for the Senate Democrats, says there will be no such trigger.

Thus far Rubio has been engaged in the positive if somewhat risky task of proselytizing fellow Republicans to his view that the party must be more open toward illegal immigrants and their families, but he can go only so far to satisfy their needs, and in the end he will have to decide whether he prefers a bill or a campaign issue. In a sign of their angst, the Republicans have picked Rubio to give the highly visible Republican response to the president’s State of the Union speech on February 12. (It has been announced that Rubio will deliver his address in Spanish as well as English.)

The Republican leaders are trying to avert the serial cataclysms they have done so much to bring on: the across-the-board cut in federal programs (the so-called sequester) that will be imposed on March 1 barring a compromise; a possible shutdown of the federal government at the end of March; and the return of the debt limit in mid-May. This government-by-crisis has threatened to define the Republicans in Washington as the party of green eyeshaded accountants with nary a thought for the well-being of the middle class, not to mention the poor. (The 2012 primaries were littered with jokes about food stamps.) That it was considered progress that House leaders persuaded the most radical members that shutting down the government was a more reasonable approach than risking another government default—and a second lowering of the US’s credit rating—was a sign of the extent to which the idea of governing has lost its moorings.

And now both sides are scrambling to avert the sequester. Republicans and Democrats have been floating proposals for ways out so they won’t blamed if the sequester actually happens. But having conceded a small tax increase on the highest income brackets to get past the so-called fiscal cliff on New Year’s Day—a move more symbolic than marking any great change in priorities—the Republicans returned to their accustomed position and declared that taxes would not be raised.

The focus on the somewhat hoked-up drama of the serial crises about funding the government has tended to obscure the more fundamental point: the Republicans are succeeding in pushing the president toward precisely the wrong economic policy for a nation still coming out of a severe recession. The Washington debate is dominated by the argument—based more on ideology than on history and betraying ignorance of the fate of European nations that have blundered into ruinous austerity programs—that the most urgent thing to be done is to cut spending. That proposition has become such a truism that neither the president nor a significant number of elected Democrats are willing to publicly challenge it.

Americans who long for a group of moderate Republicans with whom a Democratic president might deal—Bill Clinton enjoyed such help if he didn’t always use it wisely (and thus failed to pass a health care bill)—are in for a disappointment. That Republican Party is gone and the base of the party isn’t going to permit its return, at least not for the foreseeable future. If anything, the party lines are hardening. The Republican leaders are desperately trying to make sure that the kinds of nutcases that have received nominations for Senate seats in the last two elections, at the expense of more reasonable candidates, only to go on to lose what were likely Republican seats, will no longer jeopardize their party’s fortunes. Karl Rove, though his effort to boost the Republicans’ successes through milking donors of over $100 million failed miserably, is setting up an organization to try to prevent likely losers from getting nominated over more trustworthy conservatives. The trouble is it’s not always clear who is going to say something cripplingly stupid, and the whole idea, quietly supported by some party leaders, isn’t sitting well with the grass roots who will not take dictation from “the establishment” on whom they should nominate.

Finally, underlying the rigidity that has characterized the Congress in the past few years is a structural formulation that does not bend with breezes. As Nate Silver of The New York Times has pointed out, there are fewer “swing” districts in the House than ever before. “This means,” he writes, “that most members of the House now come from hyperpartisan districts, where they face essentially no threat of losing their seat to the other party,” though Republicans are more at risk of primary challenges. The great shift toward the right on the Republican side occurred in 2010, when participation, as usual with off-year elections, was limited to the most zealous. The result was a dramatic increase in Republican control of entire state governments—from which have flowed the laws, backed by the Koch brothers and other conservative donors, to break up public employee unions and tighten restrictions on abortions to the point of effectively strangling Roe v. Wade, as well as the efforts to fix federal elections through restricting voting rights and perhaps even tinkering with the electoral college and, of course, the highly consequential power of reapportionment.

The country is at a hard place: Is it going to be governable? The great challenge of returning to a workable government is to create parties that can sort out our differences without threat from extremes that weaken the democratic system. People in despair over politics in Washington might be well advised to start paying more attention to who gets elected to their state capitals.