Paul-Julien Robert is an angry young man. And he has every right to be. Robert was born in 1979 to a young Swiss woman living in Friedrichshof, a famous, and later infamous, Austrian commune that was once the largest in Europe. Like so many utopian communities founded over the past two centuries on the principle of participatory democracy, this one was the brainchild of an individual visionary. He was Otto Mühl, a former Wehrmacht soldier who in the Sixties helped found the Actionist art movement in Vienna and who gained notoriety for his scoptophilic “performances” that involved naked people rolling around in paint and mud and feces groping each other, and often ended with Mühl either defecating on someone or urinating in a performer’s mouth. (YouTube will introduce you to his chefs d’oeuvre.)

In the early Seventies Mühl created a Wilhelm Reich-inspired group called the Aktionsanalytische Organisation (Action-analytical Organization), whose program was to liberate society from its psychological dependence on repressive bourgeois norms and consumerism through free love, let-it-all-hang-out group therapy, and a return to nature. He began acquiring followers and soon moved them to Friedrichshof in eastern Austria, where they eventually built an enormous complex that housed dozens of children, who slept communally in one area, and many more dozens of adults, who slept communally in another. They worked together, bore children together, educated them together, and spent their evenings entertaining each other. Films of the earlier years make the place seem idyllic. But over the years Mühl became increasingly dictatorial and in the Eighties it came to light that he was sexually abusing some of the children. The commune was dissolved, and in 1991 he was convicted of pedophilia and spent seven years in prison. He died this past May at the age of eighty-seven.

This is the environment Paul-Julien Robert grew up in, and which he evokes to devastating effect in his first film, Meine keine Familie, a documentary that recently opened in Austria and is now making the festival rounds. The title—which literally means “My No Family”—is a dark play on the common German phrase meine kleine Familie, “my little family.” An English title given in the press packet, “My Fathers, My Mother, and Me,” softens the force of the original and masks the fury that courses just under the film’s surface. Robert’s demeanor is calm but the questions he asks are sharp: How could parents have subjected their children to Mühl? What were they thinking? And why did my mother not protect me?

To make the film, Robert relied largely on the vast videotape library that the commune had amassed to document its experiences. We see footage of smiling long-haired men working the fields and women with closely-cropped hair running around topless, a baby hanging from each teat. We see naked children playing in the mud or smearing themselves with paint, as in a Mühl performance, to the delight of the grown-ups. We see a group of naked adults making a communal dash to a lake and diving in simultaneously, a scene that brings to mind the creepy German “physical culture” documentaries of the Thirties, which did so much to shape Leni Riefenstahl’s aesthetic. And we see a room full of naked adults rolling around on the floor in a therapeutic group grope, sometimes jumping up to deliver primal screams before diving back into the scrum. Robert also mixes in clips from Austrian news reports on the commune conducted by square journalists who posed square questions and obviously just didn’t get it, man.

But Meine keine Familie is no straightforward historical documentary on the rise and eventual collapse of Friedrichshof, or on the commune experiments of the Sixties and Seventies more generally, though it is certainly an indictment of these. It is instead the record of a young man’s quest to find out just who his father was. When Robert was born, a male commune member was assigned to be his legal father, since in the days before DNA testing paternity could not be established with certainty. He and his mother went through a marriage ceremony so he would be recognized as legitimate by the Austrian state, and in fact this man did keep an eye out for the boy. Then he committed suicide. And from then on Robert became obsessed with discovering and meeting his biological father. DNA tests were eventually performed and he learned that his father was another commune member who had been sent by Mühl to develop some property in the Canary Islands and never returned. We meet him in the film and he turns out to be a very nice and very tan older gentleman with a conventional family in a conventional house. Robert takes his mother to meet him and they have some equally nice but affectless chats around the dining room table. There are no emotional scenes, no epiphanies. The film is only half over and the focus shifts to its real subject: Robert’s mother.

Advertisement

Why she subjected herself to this ordeal is the film’s great mystery. She accompanies her son on many of his travels and is interviewed at every stop. She tries to remain serene as her son keeps pressing her for justifications of the commune experience. Things get especially uncomfortable when he interviews other commune children who are still nursing their psychological wounds and trying, usually unsuccessfully, to establish healthy relations with others. Step by step, Robert is building a case against her, and all she can do is take it. The weightiest charge is that she robbed him of normal family relations and of a father, leaving him emotionally stunted. Yes, there were many loving men in the group who were devoted to the children as a group, but no figure of authority and security devoted just to him. Another is that she failed to educate him or prepare him for life “out there.” Mühl’s pedagogical idea, common enough at the time, was that to build free spirits all you had to do was let kids play. And so they spent most of their time drawing, painting, running around in nature, and putting on performances of music, dance, and comic skits, rather than learning about the outside world. That might not have been so bad had these performances not turned into Otto Mühl’s private theater of cruelty.

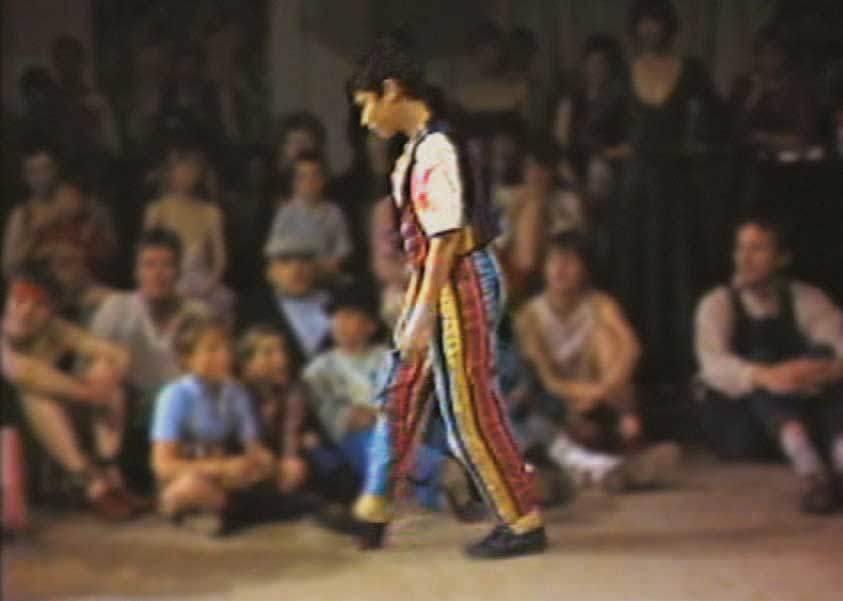

Several times a week the entire “family” would gather for these performances, which Mühl would direct while seated in a throne-like chair, holding a microphone. Adults would get up and do free-form dance or present little vaudeville acts, hamming it up for the kids. And then all the children would perform together, singing and dancing beautifully (that part worked), or they would be called up one-by-one to do an act. These are the most riveting of the film clips used in Meine keine Familie. They begin to convey the claustrophobia the children must have experienced with Mühl, who would bully and bark orders over the mike: Stand! Sing! Move! Nein, nein, nein! The most excruciating moment comes when a very young boy who clearly hates performing is made to get up at the microphone. Mühl barks at him to start but all he can do is cry. Mühl then leaps out of his seat with a bottle of water, threatening to pour it over the boy if he doesn’t start. The nearly hysterical child starts blowing into a harmonica as his tears flow, but then can’t go on. Mühl empties the water on him, orders him off stage, and shouts that he’ll have to do it tomorrow.

It is only after this scene that the pedophilia is brought up, a subtle narrative move on Robert’s part. We are shocked but not surprised, given what we’ve seen so far of the megalomaniacal Mühl. Robert himself was not abused but we meet some young people who were. We learn from them that as the children grew into adolescence girls were regularly taken to Mühl for sexual initiation, while boys would be taken to the woman he called his wife for the same reason. And parents let this happen, either knowingly or out of studied ignorance. After being released from prison Mühl made a public apology for his behavior, but in subsequent interviews he seemed anything but repentant. In one, which Robert excerpts, he brags about how all the commune women wanted to sleep with him and how hard it was to escape them. Some even followed him into the toilet, he says, and wanted to wipe his bottom.

So what drew so many young people to this sociopath and kept them with him for so many years? Why did they adore him? Why did they turn a blind eye to the way their children were treated? To Robert’s evident frustration, his mother is unable to enlighten us. She is neither defensive nor flighty, just very adept at keeping reality at bay. One feels sorry for her, too. She tears up occasionally and says her son has the wrong picture of what it was like. Mühl was not so important, she says; we made our decisions together. The children seemed happy and they were saved from the stifling, soul-destroying childrearing practices of the middle classes. But she has no answers, and isn’t eager to find any. She is old now, nicely dressed, soft-spoken and all suffering. One sees that she has trouble digesting her son’s revelations and confessions; she genuinely has no idea how the experience scarred him. It’s not evident that the son understands that, or sees that she, too, suffered from the collapse of her illusions. He’s a sensitive but pitiless young man, which is what makes this such an extraordinarily gripping film. He does what Orestes would have done to Clytemnestra if someone had given him a camera.

Advertisement

Meine keine Familie is distributed by Freibeuterfilm. A trailer with English subtitles can be seen on the film’s website.