On the inside of the cover of the program for the memorial for Tom Foley, the former House Speaker who died on October 18, is a quote in which he had said:

In a cynical age, I still believe that we must summon people to a vision of public service….for, in the end, this ethic determines more than anything else whether we will have citizens and leaders of honor, judgment, wisdom, and heart.

An amazing assemblage gathered at the Capitol on Tuesday to pay tribute to this unusual political figure. The memorial for the former congressman from Spokane, Washington, who served for thirty years and rose to be Speaker, drew: two presidents (Obama and Clinton); two vice presidents (Biden and Mondale); the current Speaker John Boehner and two former Speakers—Newt Gingrich and Nancy Pelosi; the entire House Republican and Democratic leadership; the Senate Majority and Minority Leaders, Harry Reid and Mitch McConnell; the ambassadors of Japan, Great Britain, and Ireland; numerous members of the House and Senate, most of whom had served with Foley; plus hundreds of people—Democratic nabobs and contributors, former Foley aides, and many others who had crossed Foley’s path at some point in their lives and remained attached to him, and lots of the multitude of friends whom Foley attracted. He was a large, friendly, polite, and decent man, a great Irish storyteller, perceptive and thoughtful about politics—people simply liked to be around him. Obama and Boehner sat on either side of Foley’s wife, Heather, who had served as his unpaid staff member from the time he entered Congress until he left, and most of the speakers that afternoon paid special tribute to her, a force herself. It was reminiscent of the opening passages of The Guns of August, when all of the European Royalty turned out for the funeral of Edward VII.

About five hundred people not only filled all the seats placed in Statuary Hall for the event, but stood three deep along its walls. They were there mainly because of what Foley had stood for. Washington, D.C., is a town of people who are very busy or like to think that they are. The country’s most powerful political leaders, some of them bitter opponents of each other, set aside other matters for more than two hours that afternoon in order to honor a man whom most Americans had little memory of, and who was not, in this most transactional of cities, in a position to do any of them any good now.

The people who came knew that the quote in the program represented Foley’s essence. It was only one demonstration of the fact that he understood that our democracy wasn’t to be taken for granted, that good people needed to work to keep it. While he didn’t take himself too seriously—he was a nice guy who didn’t make people feel that they were in an August Presence—he took politics very seriously, saw it as a most honorable course, and he treated his colleagues with respect and an uncommon fairness. Virtually every speaker that day recognized this.

Those present also knew that Foley stood as an emblem of a time that now seemed very long past and was perhaps unrecoverable. The fractiousness that had been developing almost from the day he stepped down as Speaker, having been defeated for reelection in the Republican sweep of 1994, reached its apogee at the hands of some of the very people sitting there paying tribute to him.

The event brought out the surprising best in certain figures. In his opening comments Boehner was gracious and warm; McConnell, too, showed warmth, humor, and respect for Foley, though they didn’t agree on many things. One had no sense that these were canned, politically expedient comments, memorial potboilers drawn up by staff. Something about Tom Foley broke through the conventions. I remarked to a friend later that this was a memorial during which nobody had to lie.

Shortly after he was elected Speaker in 1989, Foley proposed to the minority leader, Bob Michel, that the two of them meet once a week, first in the office of one of them and the following week in the other’s. They did so throughout Foley’s speakership. Such an arrangement now is unimaginable. Foley often crossed the House floor to sit and confer or shoot the breeze with Michel. And so at the memorial, after a series of short speeches by some of Foley’s closest colleagues in the House, the ninety-year-old Michel, by now frail and stooped and needing assistance, approached the podium. One worried that Michel might not be up to the demands of the moment. But as soon as he started talking—with his characteristic ruddy cheeks and cherubic face dominated by a broad smile—Bob Michel’s great baritone voice filled the vast hall. Foley was fortunate to have had as his counterpart this plainspoken representative from Peoria—who never became Speaker because the rising Gingrich forces saw him as too friendly toward the Democrats, which Michel’s supporters argued was the way to strike bargains on their proposals. Michel was also of a positive temperament, almost the last of the guard who put the institution and accomplishing things over sheer partisan competition and combat. In his tribute to Foley, Michel said, “We both saw the House of Representatives as one of the great creations of a free people.”

Advertisement

Michel spoke of the time in 1994, when Foley had just been defeated for reelection—a shocking development, the first Speaker defeated since the Civil War—a devastated Foley asked him to preside while he made his farewell remarks to the House. Michel told of the talk that he and Foley had then about their mutual pride in what they had achieved together, substantively and as an example of how the House should work. And then, Michel said, they spoke of it again years later when Michel visited Foley as he lay dying in his home not far from the Capitol. “We both felt good about that.” Obviously aware of what had become of their beloved institution, Michel, with the main destroyers sitting before him, said, “I only hope that the legislators who walk through here each day will find his spirit, learn from it, and be humbled by it.” Voice choking, growing softer, Michel concluded, “that is what I have to say in honor of my dear friend Tom Foley.” The audience rose at once to its feet to applaud him—and them. No such clearly felt sentiment seemed likely again.

In her courageous closing remarks, Heather Foley said that her husband often came up with arguments for his point of view that amazed her—“Where did he get that?” In a debate in Spokane in the late Sixties over Foley’s support for a some gun control despite strong opposition in that part of the country, he stood on a stage for over five hours, debating a man who had challenged him to argue the issue. Toward the end of the long debate, Foley responded to a charge from an audience member that the Soviet Union had succeeded in overrunning Hungary, in 1956, because Hungary had controlled gun ownership. Foley replied by pledging that he was opposed to controls over people’s rights to own bazookas and stock missiles in their back yards.

As usual, Bill Clinton, who spoke after Bob Michel, dazzled with his talent for imagery, his apparent passion, his humorous lines. He rarely consulted his notes as he told stories to make his points. Portraying Foley as a politician of courage and unusual insight, Clinton recalled that just after he had been elected president and asked Foley to come to Little Rock to tell him what he was in for, the Speaker warned the new president against pursuing an assault weapons ban. We can win it, he said, “but there will be a lot of blood on the floor.”

Clinton spoke of the terrible hurt that Foley suffered when he was defeated in 1994. Having loved his district and the House, Foley took the rejection hard, as happens to serious politicians; it feels personal, it is personal; it’s a public rejection. Clinton, as he was wont, attributed Foley’s defeat, like that of others in the Republican sweep, to the assault weapons ban that Clinton had gone ahead with. But, actually, Foley’s defeat, like most of them, was a result of a combination of forces, including the Clintons’ inept handling of Mrs. Clinton’s health care bill; Foley’s strong opposition to a new state law setting term limits; a mysterious $300,000 in outside money, a tremendous amount for Spokane, that had come into the race against him; demographic changes in his district; and his opponent’s use of the increasingly fashionable faux populist attacks against an incumbent as being “out of touch” with his district. The gun control issue was of but marginal importance; it didn’t defeat Foley. But Clinton, his familiar thin left index finger poking the air, his eyes-narrowing, lip-biting show of intensity, for years remained insistent that the assault weapons ban (nothing he and his wife had done) caused the devastating Democratic defeat in 1994.

It’s never easy to follow Bill Clinton as a speaker; his pyrotechnics and fetching use of the English language can be mesmerizing. He shows the others how to do it. His messy presidency was largely forgotten as he became perhaps the most effective and popular political figure in the country. And so when Barack Obama got up to speak next, he looked diminished. He seemed to shrink in Clinton’s presence. Though, as he acknowledged, Obama didn’t know Foley, he did manage to avoid saying the same things about Foley that the others had. He referred to Foley’s “powerful intellect,” and indeed Foley was a serious reader, especially of history. He spoke of Foley’s “humility,” and with his own difficulties with Capitol Hill obviously very much on his mind, Obama said, “it was his personal decency that helped him bring civility and order to a Congress that demanded both—and still does.” It was clear at whom Obama’s quietly expressed remarks were aimed. But they were barely audible in the big hall, muffling any effectiveness they might have had, and there was cause to wonder uneasily what Obama even was doing there. He seemed clearly outmatched and out of his element.

Advertisement

When I rewatched the proceedings on C-SPAN later that evening, I saw something totally at odds from what so many had thought we had witnessed in the great hall. Clinton’s pyrotechnics—his long and colorful description of a funeral in Japan that he and Ambassador Foley had witnessed, the point of which was no clearer than it had been that afternoon—seemed overdone. (After leaving the House, Foley served as Ambassador to Japan from 1997–2001.) Clinton appeared to be vamping, reaching for his own relevance to Tom Foley. He had as usual put on a good show and later it seemed no less brilliant as a performance but less fitting. It was Obama who was now the far more impressive. Obama had understood that the quiet voice is more effective on television and more suitable to the occasion. His even-toned comments about civility slipped knife-like into the Republican leaders arrayed before him. He didn’t have to look at them. (The news stories later were predominantly focused on Obama’s call for “civility.”) Obama had seen the perfect opportunity to present himself as the calm, restrained, and would-be bipartisan leader by standing witness for Tom Foley. His acknowledgment that he didn’t know Foley, which seemed weak in the afternoon, now came off as plain honesty. He knew exactly what he was doing. Every once in a while Obama reminds us why he became president.

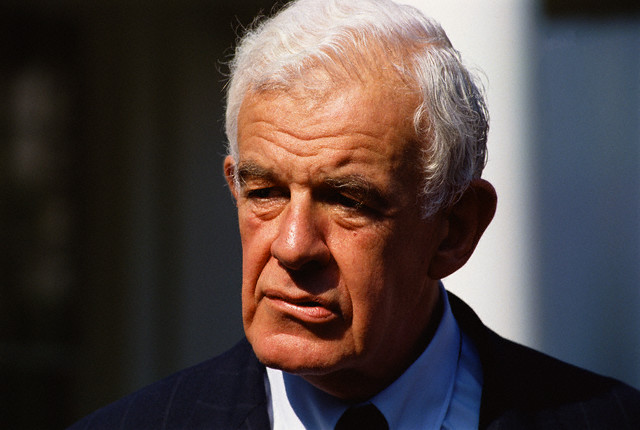

At the close of the ceremonies, as the camera focused in on a striking painting of the white-haired, strapping, dignified Foley, one knew that Washington was unlikely to again see such a figure—and certainly not to witness such an exceptional moment.