To write the history of opera production, not only must one know the repertory well, but one needs to understand the extraordinary work of the many people involved backstage who make an operatic spectacle function. Few people are as capable of writing such a history as Evan Baker, who has worked as a dramaturge and stage director for decades. Baker understands the changes that have accompanied operatic spectacles in modern times, as nonmusical influences have become an increasingly prominent aspect of the performance. In his new book, From the Score to the Stage: An Illustrated History of Continental Opera Production and Staging, he follows these changes from the seventeenth century to the present. For the history of directing, stagecraft, and lighting in particular, Baker is superb.

He describes, for instance, how stage directors have grown in importance over the course of opera’s history. There has always been some degree of flexibility in the way in which operas were staged: Verdi himself was often forced to change the time and locale of his productions. But in the early days of opera, productions often remained more or less faithful to the opera’s original stage directions, distinguishing themselves instead with elements like mechanical flourishes—pulley systems for scene changes, for instance. In contemporary opera, however, the director has full reign over the setting and tone of the entire production. This so-called regietheater or “director’s theater” has aroused a great deal of controversy. It has led to interpretations as varied as Patrice Chéreau’s beloved 1976 staging of Der Ring Des Nibelungen, which placed Wagner’s opera in the political environment of the nineteenth century and the Industrial Revolution; to Hans Neuenfels’ somewhat less beloved Lohengrin, in which all but the main characters are dressed as giant rats.

Baker treats smaller changes in opera with equal care. He notes that in the eighteenth century, lighting was often the most expensive part of the production, as, unlike costumes or scenery, candles could not be recycled from one performance to the next. When electricity provided a revolution in lighting at the end of the nineteenth century, some directors and artists were reluctant to lose the flickering flames provided by gas lighting and candles.

One can gain some sense of From the Score to the Stage by glancing at the photographs below, selected from the book’s almost two hundred illustrations. The first two images are from Antonio Cesti’s Il pomo d’oro, a significant Baroque opera, written for wedding festivities of Hapsburg emperor Leopold I and Margaret of Spain in Vienna in 1667. The third image shows the Drottningholm court theater in the eighteenth century, the only surviving theater of the period with its machinery intact. Turning to the nineteenth century, there are images from within an Italian box, of costume designs for Verdi’s Rigoletto, and of Verdi rehearsing with his cast, where, as one of his singers recalled, he “did not care if he wearied the artists and tormented them for hours on end with the same piece.” Not surprising, many images relate to Wagnerian productions, since much recent stagecraft derives from efforts to mount Wagner’s operas: there is an early image of the three Rhinemaidens from Das Rheingold, and a scene from Chéreau’s Die Götterdämmerung. There is also an image from a Russian opera by Rimsky-Korsokov, whose opera Le coq d’or featured Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Baker limits his discussion of the history of operatic staging to Continental productions, although he acknowledges the importance of some contemporary staging in America by including an image (reproduced here) of a scene from Tan Dun’s 2007 Metropolitan Opera premiere, The Last Emperor. Over the past few decades the Met, as well as other American theatres, has featured interesting productions, including the recent The Nose by Shostakovich, in a production designed by the South African artist William Kentridge. Yet it is certainly the case that the history of staging opera and of theatrical innovation over the past four hundred years has largely been European.

Baker’s treatment is particularly rich in the documentation of these changes, and it will please all those who love the art form traditionally understood as “opera.”

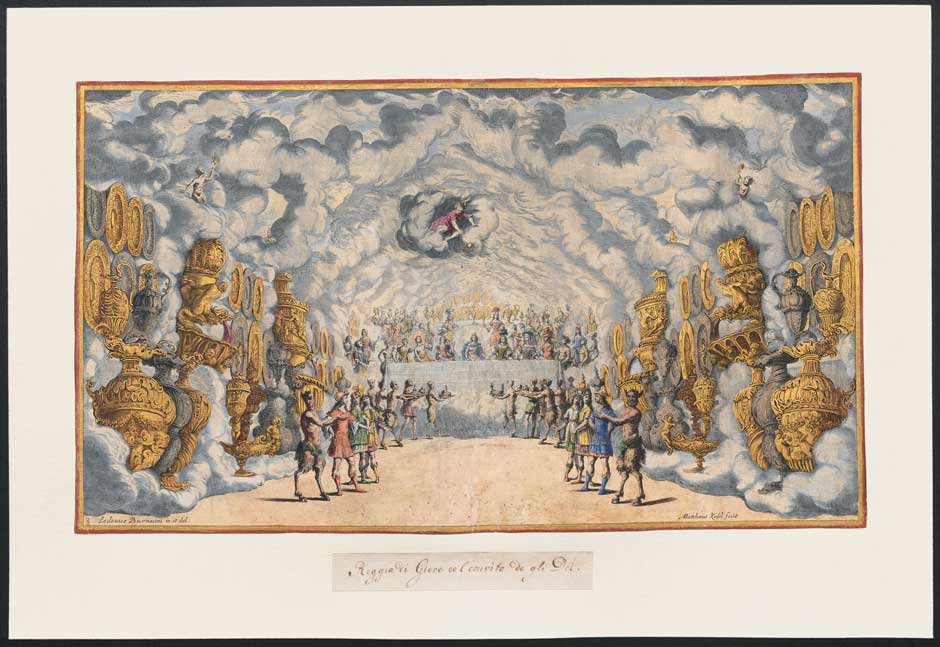

Musikammlung Der Osterreichischen Nationalbibliotek, Vienna

Lodovico Burnacini: Il Pomo d’Oro, Act I, Scene V, Jupiter and His Court at Banquet with Discord Floating in a Cloud above the Table, hand-colored engraving, 1668.

A magnificent scene from Antonio Cesti’s Il Pomo d’Oro (The Golden Apple), in the heavens of the gods feasting at a banquet. The setting utilized much of the depth of the stage, with at least six sets of wings and borders depicting clouds and wine casks at the sides and top. At the rear, the gods, personified by Emperor Leopold I and his wife, Margaretha, are seated at a table on a platform above the stage, served by choristers and supernumeraries costumed as satrys. Above the gods, Discord has arrived in her cloud machine, hurling down a golden apple, inscribed “To the fairest,” thus setting off a contentious dispute between the goddesses Juno, Venus, and Minerva.

Advertisement

Musikammlung Der Osterreichischen Nationalbibliotek, Vienna

Lodovico Burnacini: Il Pomo d’oro: Act II, Scene V, The Abyss of Hell, hand-colored engraving, 1668

“The earth opens up, and an enormous and hideous head arises and takes up the entire stage; the gaping maw opens up to another abyss, through which is seen the river of Hell with Charon and his boat at a landing; in the distance, fire circles around the domain of Pluto.” Twenty-five engravings of scenes from Antonio Cesti’s Il Pomo d’Oro (The Golden Apple) accompanied the first Italian (1668) and German (1672) editions of the libretto; this scene is the eighth. The Furies Alecto, Tisiphone, and Megara fly before the frightful scene with burning torches, singing of the woes caused by Discord and the Golden Apple. Burnacini, in his stage renditions, exploited the libretto’s apt descriptions to the fullest.

Rolf Hintze/The Music and Theatre Library of Sweden

Lorens Sundstrom (attributed): En Odenmark (A Wilderness), stage setting at the Drottningholm Slottseater, Sweden, around 1777

The Drottningholm court theater is the only surviving baroque stage with its original machinery intact. Seven wings, each attached to its own chariot, represent a rocky “wilderness” of painted shrubs, broken branches, and waterfalls within a single-perspective view to the center of the stage. At the rear of the setting is a seashore, with three large, cylindrical “corkscrews” of “ocean waves” spanning the width of the stage.

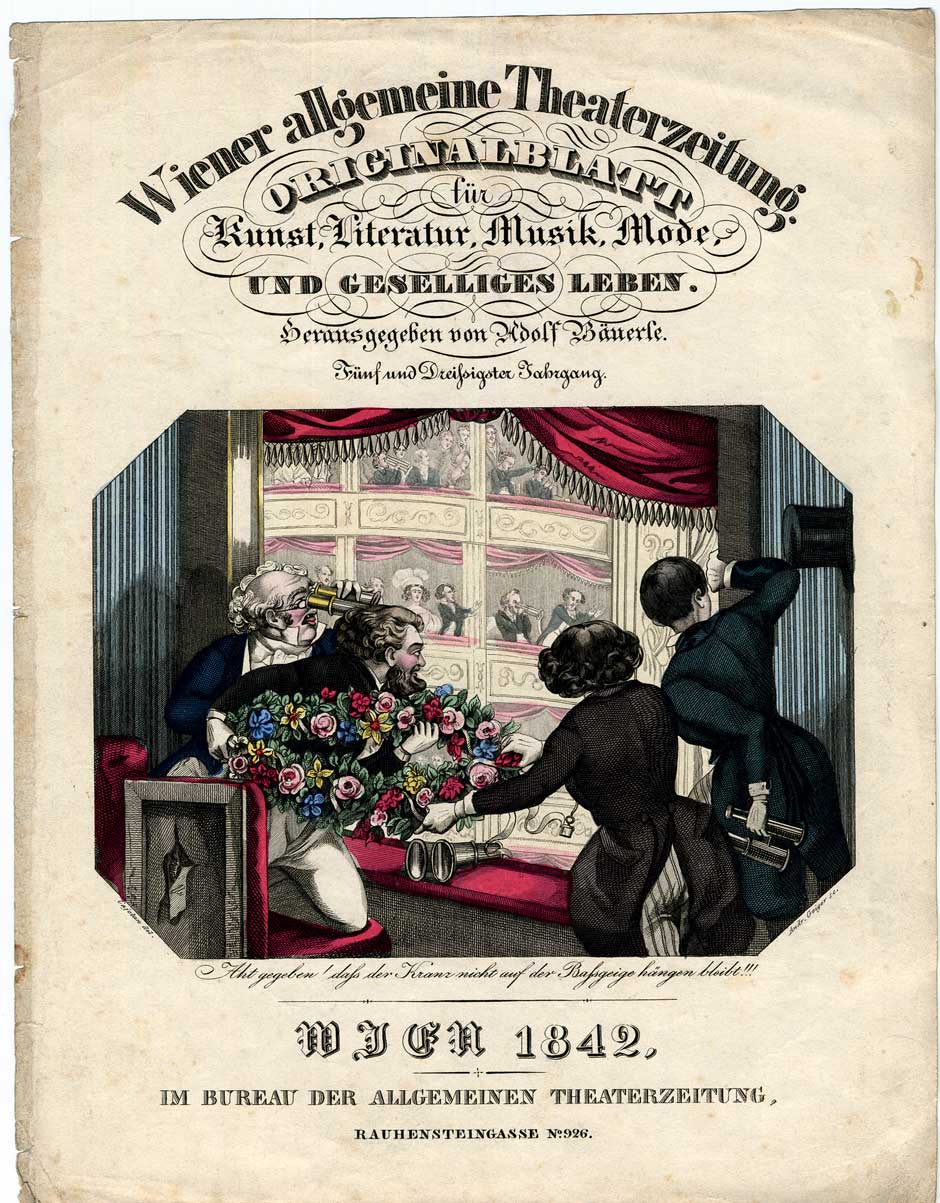

Evan Baker

Cajetan (Anton Elfinger): “Watch Out That the Wreath Doesn’t Land onto the [Neck] of the Double Bass!” From Weiner Allgemeine Theaterzeitung: Originalblatt fur Kunst, Literature, Musik, Mode, und geselliges Leben; Herausgegeben von Adolf Bauerle; acquatint, 1842

Like their Italian counterparts, audiences in German-speaking countries idolized many singers and were not afraid to express their feelings. Here, perfectly coiffed, white-gloved dandies prepare to hurl a large, flowered wreath from the gallery to the stage during the applause at a curtain call. At left is a shabby seat with ripped fabric in its back, and one of the dandies is viewing the stage with long binoculars, as are others in their boxes with even longer binoculars.

Parma, Casa Della Musica, Archivio Storico Del Teatro Regio

Costume Designs for “Rigoletto”; hand-colored lithograph, after 1851

For Guiseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto, the publisher Ricordi printed twenty-one figurini depicting the lead characters in their costumes during the opera. The figurines were available for sale to all interested theater managers and impresarios.

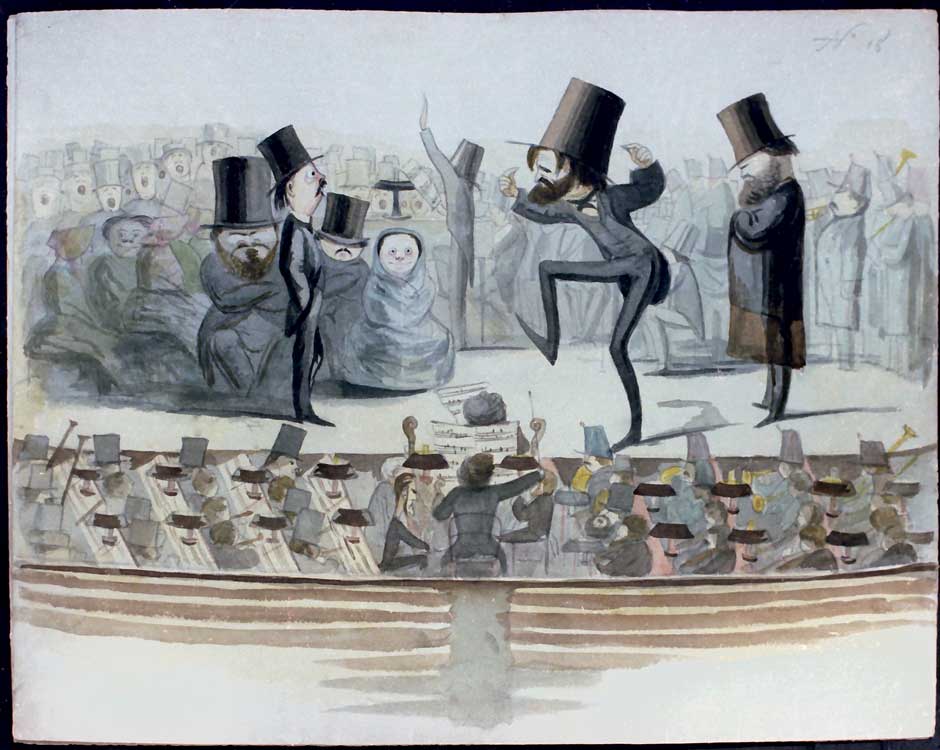

Evan Baker/Sant'agata, Villa Verdi

Melchiorre Delfico: Verdi Rehearsing with the Soloists, Chorus, and Orchestra for “Simon Boccanegra” at the Teatro San Carlo, Naples, pen, ink, and watercolor, 1858

A furious Verdi snaps his fingers and stamps his feet to give the beat to all the diverse groups—including the local military brass band at the right—assembled for a music rehearsal. As a conductor did not yet exist, the concertmaster at the center in front of the prompter’s box with his violin bow is giving the beat to the orchestra and perhaps out of sync with Verdi’s. The chorus sings lustily and the military band contributes to the cacophony.

Evan Baker

J. Albert: Costume Portraits of the Bayreuth Festival: Minna Lammert, Lilli Lehmann, Marie Lehmann as Rhine Daughters, 1876

Assistant stage director Richard Fricke noted in his diary, “I am not yet certain if and how the singers will have the courage to lie in that machine and—sing. Not that they will be able to sing in a half-reclining position, but because of sheer fright they won’t be able to make a sound!”

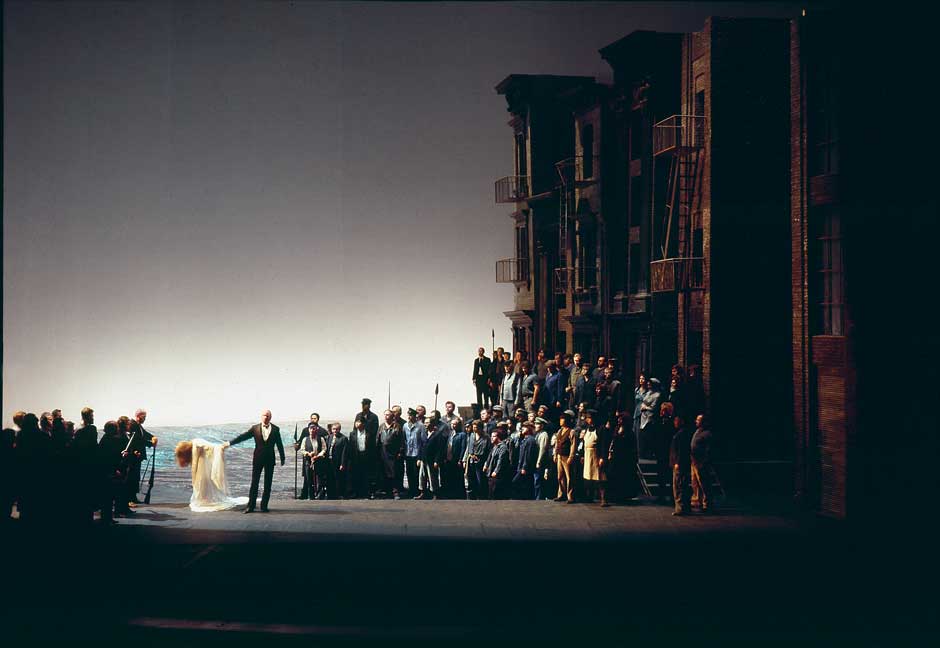

Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

Tan Dun’s The First Emperor, Metropolitan Opera, New York City, 2007

The high-definition broadcast of a live performance from the Metropolitan Opera in New York City was seen in movie theaters throughout the United States. The practice has since been copied by American and European opera houses. The production was by Chinese film director Zhang Yimou, and the set designer was Fan Yue.