It’s intriguing how little is said about the anthropology of reading, who reads what and why and what we understand about each other seeing the things friends read or hearing their differing opinions when for once we read the same thing. It’s now a commonplace that there is no “correct” reading of any book—we all find something different in a novel—yet little is said of particular readers and particular readings, and critics continue to offer interpretations they hope will be authoritative, even definitive.

In this regard, I’ve been thinking how useful it might be if all of us “professionals” were to put on record—some dedicated website perhaps—a brief account of how we came to hold the views we do on books, or at least how we think we came to hold them. If each of us stated where we were coming from, perhaps some light could be thrown on our disagreements. Here is my own contribution.

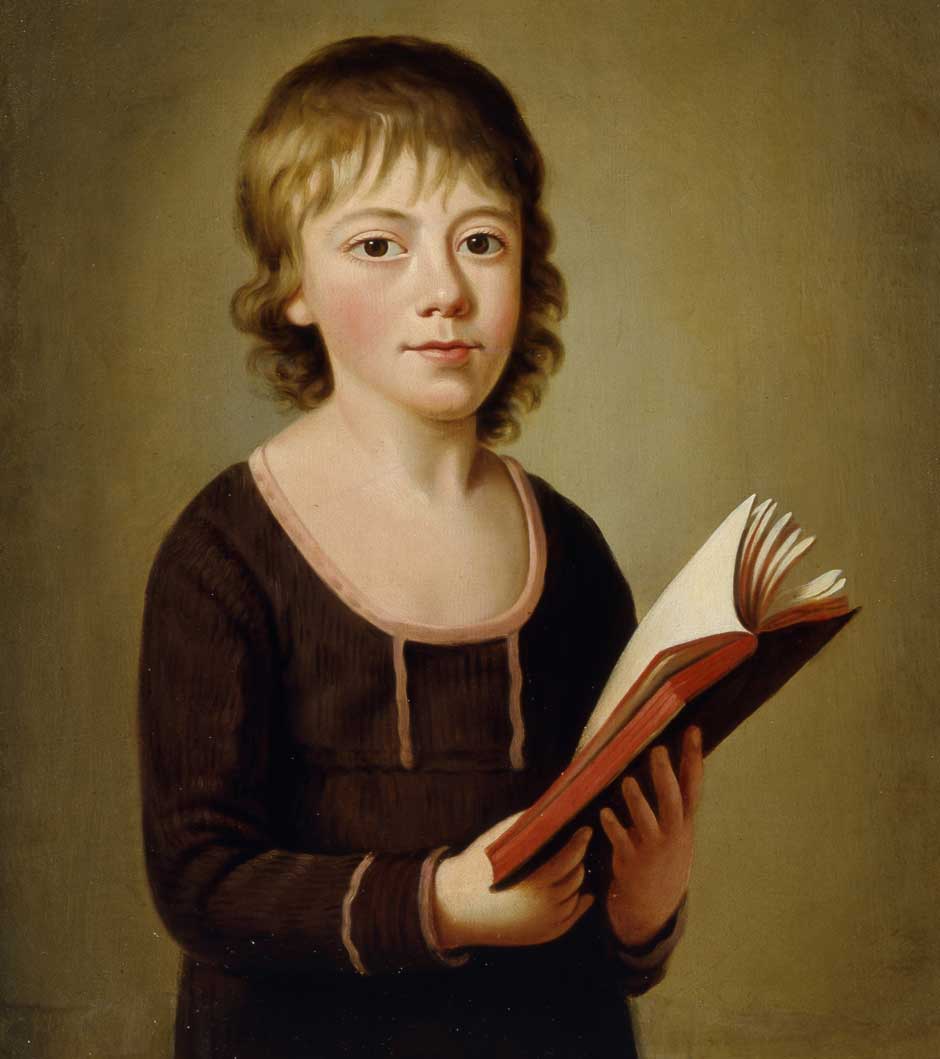

Books began, in my case, when my parents read to me, so I knew from the start that reading must be a “good” thing. Fervently evangelical—a clergyman and his wife—my parents only did things that were good. They read us children’s stories and the Bible. Later I exploited this faith of theirs in the essential goodness of literature to plot my escape from the suffocating world in which they lived and wanted everyone else to live.

When they read to us, a daughter and two sons, perhaps beside a smouldering coal fire, with an evening cup of cocoa, the books created a feeling of togetherness; we were united in one place in the thrall of one parental voice, my mother’s usually, and afterward there was a shared store of stories and memories that made us a family. But when I read alone, searching out books that offered a broader view of life, books isolated me and divided us. Now I had ideas and arguments that countered theirs. I read avidly, safe in the knowledge that they thought this was a good thing. But soon enough they picked up my copy of Gide, of Beckett, of Nietzsche; then there were tears and conflict. Away from the Bible and children’s books, reading was not always good, and when it wasn’t good it was bad. Very bad.

Even today there is a subtle tension in my reading between the desire to free myself from the immediate community with its received ideas, and the desire to share what I read with those around me, those I love. On the other hand, it was perfectly clear to me in adolescence that when we read alone each member of the family would choose quite different books, and that what you were reading inevitably declared where you stood on the things that mattered in our house. You had to be careful when you chose to share a book.

My father’s study was wall-to-wall Bible concordances, huge tomes in scab red covers, each brittle page divided into two yellowing columns and peppered with text references, brackets, footnotes. A glance was enough to tell me I would never read them. Perhaps they inspired my life-long impatience with books that seem over-technical: jargon-ridden works of literary criticism, for example. I connect them with my father. There was something unhappily withdrawn about his study; he hated noise; no one could challenge him in his knowledge of the Scriptures. But it did not seem like all that cross-referencing had much to do with living and breathing. My family created a situation where I went to books for fresh air, not scholarship.

Mother had no shelves of her own but supplied the books kept in a small rotating mahogany bookcase in the living room; these were family books where goodness was not a theory but a question of warm, benevolent emotions or, perhaps, swashbuckling patriotism. Dickens had the most space I suppose, closely followed by the adventure stories of a British World War II pilot with the improbable name of Captain Bigglesworth. John Buchan was there, and The Secret Garden, and Water Babies, and of course, Three Men in a Boat. This was permitted reading. I read them all and felt hungrier than ever.

Right at the back of the cubbyhole under the stairs, where you had to get on your knees as the ceiling came down to meet the floor, wrapped in thick brown paper and tied in string, was a book published in the 1940s about marriage and sex; it included some instructions as to how to go about making love if you never had before. Things like: Don’t be in a hurry to get all your clothes off. Think of your partner’s pleasure as much as yours. This book, whose title I have forgotten, was hugely useful to me. It was also interesting to discover that my righteous parents did this stuff, and again that the book could not appear on other shelves in the house. Evidently, there were books that were good, or for the good, but not good for everyone at every moment.

Advertisement

In my sister’s room, painted pink with flowery curtains and a pink bedspread, the shelves were full of Georgette Heyer and similar romances of a historical flavor. At some point I must have noticed the relationship between the book covers and the room’s decor. This was the aura my sister moved in. Five years older than me, she played the guitar in church and was always prayerful; anything to do with sex had to come in a patina of propriety and pink. I read about half of a Georgette Heyer novel, but did not find it useful.

My brother, the middle child, was the rebel. In his bookshelf, among sundry science fiction by Asimov and Ballard, not even hidden, was a paperback called Lasso Round the Moon by Agnar Mykle, published in 1954 (the year I was born). Paperbacks were new to me. There was a photograph on the cover that promised sensual not spiritual bliss. I understood at once that only certain sections of this volume need be read. They were already well thumbed.

It will seem all too easy, this fusion of topography and attitude, but it’s true: my room was sandwiched between my brother’s and my sister’s. It too had a bookshelf. There were no rosy historical romances, no girls clutching a last shred of clothing to their modesty. There were no concordances, no innocent children’s books. Way before I could possibly understand them, there were Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and Chekhov and Flaubert and Zola. These books were foreign. Out of it. They never gave me the crasser joys I craved, but then again they never made me feel I was merely indulging, or merely provoking; I wasn’t locked in a fight with my parents, as it seemed to me my brother was. Neither good nor bad, they were good and bad, there was adventure and debate. If my parents made the whole world black and white, these books were colored and immensely complicated.

Over the past year or two I’ve realized how much this organization of the books in my childhood home still influences my reading and reviewing. When I negatively reviewed a book like William Giraldi’s Busy Monsters, it was because it seemed to me an exercise in literary exhibitionism; intellectuality as an end in itself, self-indulgent performance whose main intention was to encourage the reader to concede that the author was smart, rather as if those biblical concordances had been rewritten by Agnar Mykle. When I admired aspects of Dave Eggers it was because I recognized his constant division of the world into good and evil, and when I doubted him it was because in the end it seemed to me he was preaching. The analyses I offered of Fifty Shades of Grey and Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy were very much operations in understanding their position in the geography of our old family bookshelves. Funnily enough, their immense success immediately makes sense when described in this way. They are both books that allow you to read a little hard violent sex while siding with a hero or heroine eager to eliminate such things from the world. Anyone turning to my piece on Peter Matthiessen in the present edition of The New York Review will now understand both my attraction to his recent novel and my reservations.

Will I never escape from this? Is it a miserable limitation? Should they stop commissioning reviews from me? We all have our positions. Identity is largely a question of the pattern of our responses when presented with a new situation, a new book. Certainly the idea of impartiality is a chimera. To be impartial about narrative would be to come from nowhere, to be no one.

The challenge, I suppose, is to be aware of one’s habits, to be ready to negotiate, even to surprise oneself. I still recall my perplexity, then growing pleasure, when I read Peter Stamm a couple of years ago: first a sense that his novels were truly different; not the fireworks of would-be experimentalism, but a voice I hadn’t heard before. I had to struggle to place it, to find where I stood in relation to it. Essentially, Stamm constructs stories that my background leads me to think of as moral dilemmas—a long extramarital affair in which the mistress falls pregnant, for example—but that his characters understand entirely in terms of fear and courage, dependence and independence. The writing is, if I can put it this way, comically serious, in its simultaneous awareness of and refusal to engage with the moral side of events. In the end I was fascinated. Perhaps it’s the books that very slightly shift an old position, or at least oblige you to think it through again, that become most precious. But what does that for me won’t necessarily do it for you.

Advertisement