American, or at least New York, lovers of the work of Piero della Francesca—love seems to be a better word than admiration to describe how people feel about this artist—have been given a rare two-part opportunity over the past year. Last winter and spring the Frick Collection brought together a small number of works by the fifteenth-century Italian painter, most coming from American museums. They were principally portraits of saints from an altarpiece, along with Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels, a strong (if not incandescent) picture from the Clark Art Institute, in Williamstown, Massachusetts. It is the one “American” Piero that gives a clear taste of an aspect of his art that made him a particularly exciting figure for painters and writers in the early twentieth century—when he crowds together a number of figures in a tight space, making them feel full-bodied yet flat, like overlapping cards you hold in your hand in a game.

Now the Metropolitan Museum, in “Piero della Francesca: Personal Encounters,” has assembled a few pictures that fortuitously complement the Frick show, which emphasized the grave and hieratic side of the painter’s art. Organized by Keith Christiansen, a curator at the Met, the current exhibition is the first ever about Piero’s devotional works. They are small-size paintings created for bedrooms or set-apart areas in the home. In spirit they take us to much the same austere and bare-bones realm as his more public pictures. Yet they present more directly and pleasurably the qualities that make Piero such a special figure, even by the heady standards of the fifteenth century, when so many Italian and Flemish artists, newly working with oil paint, were finding one personal way after another to portray the actual, corporeal world they lived in.

Piero was an obsessively methodical artist. He spent his last decades—he died in 1492, probably around age eighty—not painting but, rather, writing treatises on geometry and perspective. His goal was to bring the laws of perspective and measurement to bear on his scenes, and in the process he turned figures and aspects of buildings, even items of clothing, into so many precisely self-contained shapes. Yet his militant orderliness was of a piece with an extraordinary feeling for character and emotion. In their bearing and marvelous faces, the people in his pictures are shy, and also aloof, in a way few artists have matched. His figures can be strangely contemporary in their sexiness, and there is nothing dated about the way they encounter and judge one another, or appraise us.

Two of the works at the Met are about Saint Jerome, the fourth-century figure who translated the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin and is traditionally seen as a hermit, living ascetically in the countryside. Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, from the Gemäldegalerie, in Berlin, has lost a fair amount of its color over the centuries. But the landscape in the background, with its rhythmic bunching of trees, its well-behaved little winding river, and the reflection of the trees in the river’s mirrored surface, forms, charmingly, what might be called a mathematician’s notion of a park.

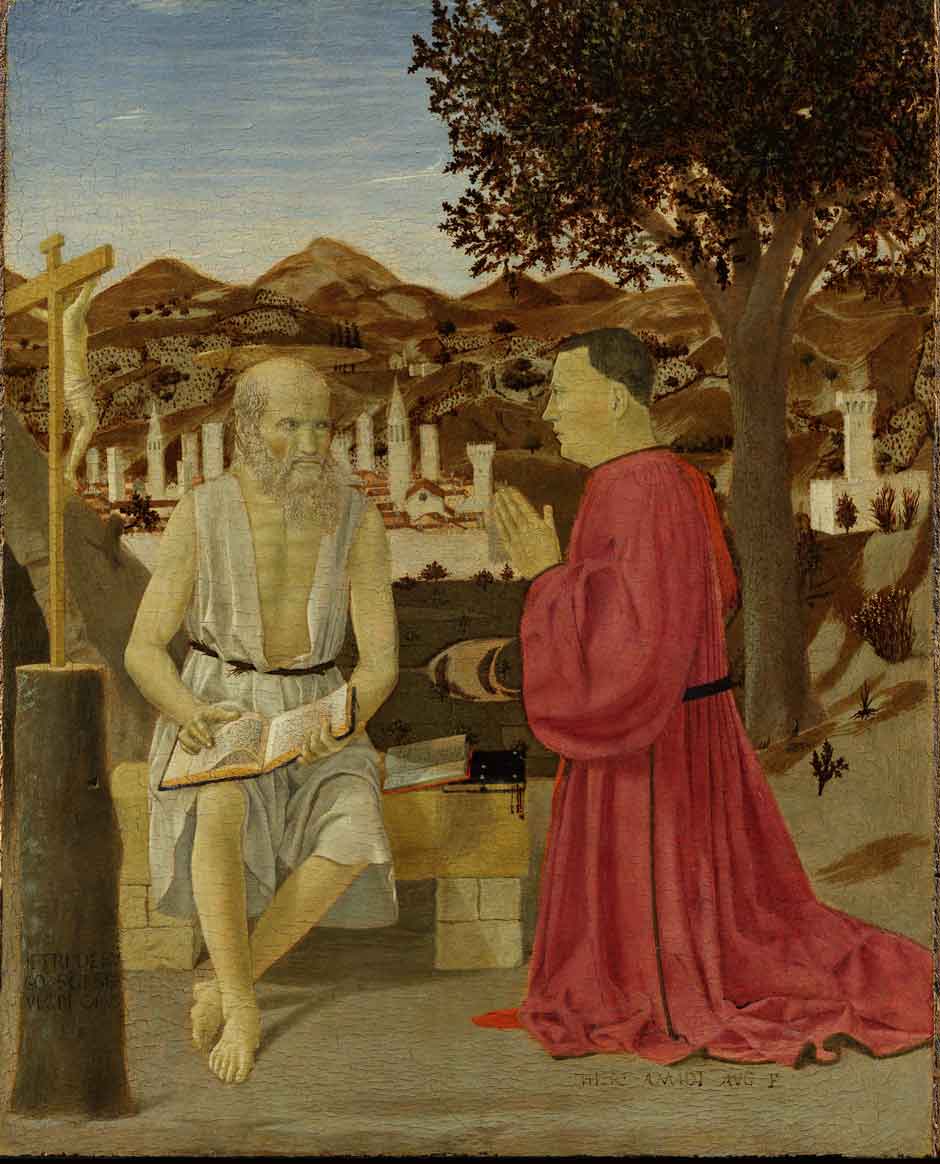

Saint Jerome and a Supplicant, which is from the Accademia, in Venice, and has recently been restored, presents an even finer background landscape, much of it showing a white town crowded with towers. The picture’s subject, however, is the encounter between our supplicant, Girolamo Amadi, with a double chin in the making, and a bald, lithe, sensuous Jerome, whose lips are pink and whose facial expression changes depending on how we see the picture. Looking at it in the catalog, Jerome seems pleasant enough, even though he has been interrupted. Standing before the actual work, though, the drawing of his features is such that he warily seems to indicate that his time is limited, and in either case there is a believable psychological tension between the men. Did Piero intend such ambiguity? He might have, because this isn’t his only painting where we are uncertain of the expression being conveyed.

The most impressive work in the show is Madonna and Child with Two Angels, a picture that is owned by the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, in Urbino, where—part of a collection that includes a matchless early Raphael portrait of a mute woman and Piero’s enigmatic Flagellation—it makes the not-so-easy, mountainous trip to this small city a necessity for anyone interested in Renaissance art. With her downcast eyes, gentle demeanor, and small features set in a large, wide-nosed face, the Madonna is a choice example of a kind of woman, at once regal and rustic, that Piero created. Her quiet strength is reiterated in the work’s painted surface, which has an enamel-like density.

Advertisement

The angel in pink is an attentive young person, but the angel in blue (who is possibly the same model seen in a different way) is, along with the suggestion of a room behind him, transfixing. Piero’s angels, whether attending a Nativity, a baptism, or a Madonna, can be guarded or genuinely sweet. They almost always have a distinct presence. The angel, or seraph, in blue here, whose arms are crossed before his chest and who might be blocking entry to the background space, would seem to be Piero’s last word on the subject. His baby-blue outfit is exquisitely touched with bits of white and gold, and his white-blond hair is set in little electrified ringlets. Kenneth Clark, in his book on the artist, called him “daunting,” and Christiansen says he is “implacable.”

But surely his protectiveness has something sensual and brazen about it, and the glimpse we have of the bare space behind him, where all we see are shadows of window blinds and a patch of strong sunlight on the wall, is uncannily of our day and age. Am I alone in thinking that this part of the picture might be set in Palm Springs? The angel and the mysterious area he is linked with form almost a painting within the painting. It is kind of a gift within the larger gift that is Piero’s art.

“Piero della Francesca: Personal Encounters” is showing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through March 30. A catalog by Keith Christiansen, with contributions by Roberto Bellucci, Cecilia Frosinini, Anna Pizzati, and Chiara Rossi Scarzanella is published by Yale University Press.