Many years ago, from a room on West Street in Manhattan where I worked, I would gaze with uneasy wonder at the riotous petrochemical sunsets that radiated into lower Manhattan from the industrial corridor of Bayonne and Newark, New Jersey. In the indescribable colors of those gaswork rays I would contemplate the peculiar aesthetic of pollution.

The photographer Steven Hirsch has had a similar response to the toxic surface of the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. Hirsch is fascinated with the pollutants that have accumulated in the relatively narrow and short (the canal is 1.8 miles long) human-made waterway over the course of its 145-year existence.

The canal was built on the cheap in 1869, to connect the small marshy stretch of western Brooklyn with Upper New York Bay. In its rush to complete it, the Corps of Engineers neglected to put in place a through-flow that would flush the canal with regular doses of fresh water. It was a toxic trap from its inception.

To live in the canal today you must be an organism that requires almost no oxygen. (The concentration of oxygen in its water is 1.5 parts per million, well below the minimum of 4 parts per million needed to sustain life.) It is an industrial graveyard for all manner of raw sewage and waste—from chemical plants, tanneries, paint and ink factories, gasworks, and cement plants, many of which are now defunct. The toxic sediment, in some places, is as thick as twenty feet.

In 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency declared the canal a Superfund cleanup site and placed it on its National Priorities List. In September 2013, the agency approved a cleanup plan, projected to cost $502 million. The cleanup will take at least ten years to complete, partly because the government has to wrest a portion of the cost from the companies that did the dumping, or at least those among them that remain in business.

Unwilling to wait for the cleanup, a real estate company called the Lightstone Group is currently building a high-end residential development with seven hundred apartments on the banks of the canal at Bond Street. Similar developments are sure to follow, though only a few blocks away residents of the Gowanus Houses—owned by the New York City Housing Authority—complain of respiratory ailments from living so close to the site. Architectural drawings of the Lightstone development show esplanades, foot bridges, and green-fringed banks alongside glass and steel residential boxes.

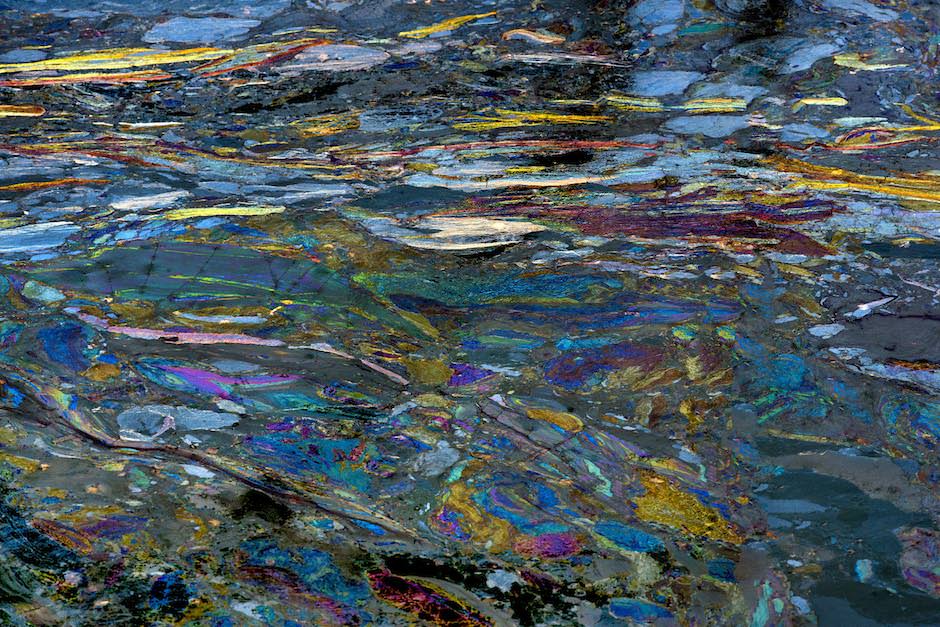

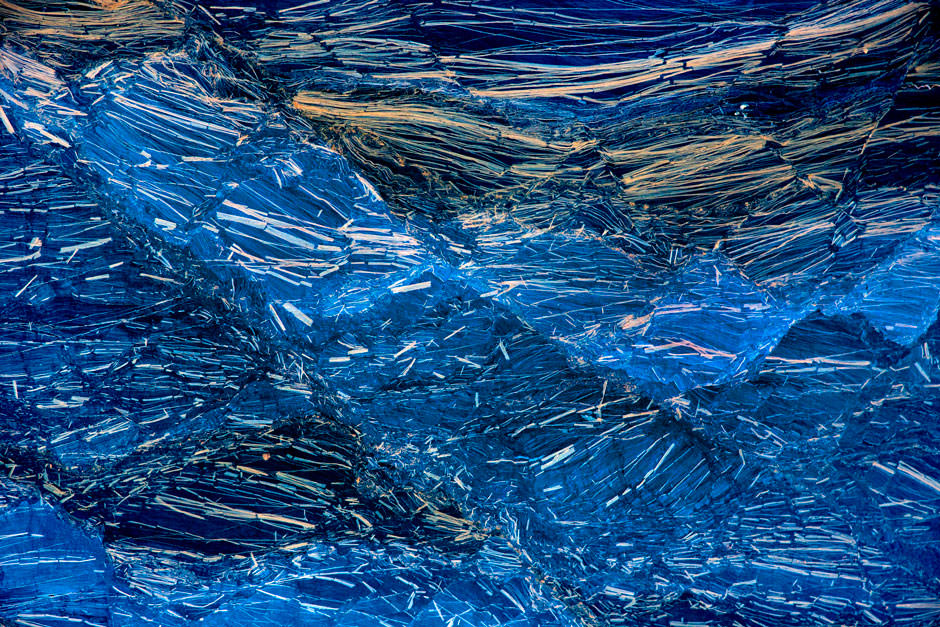

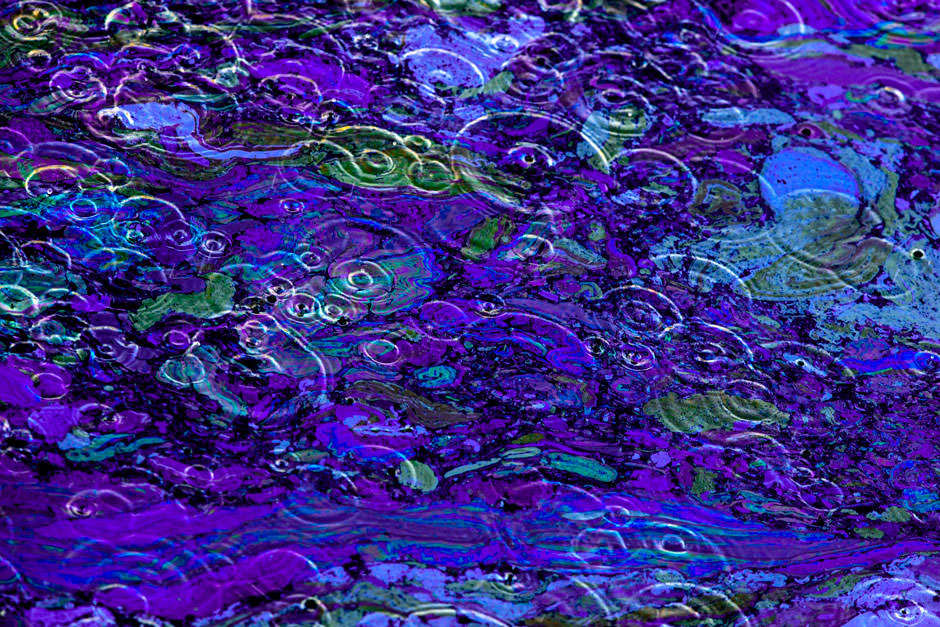

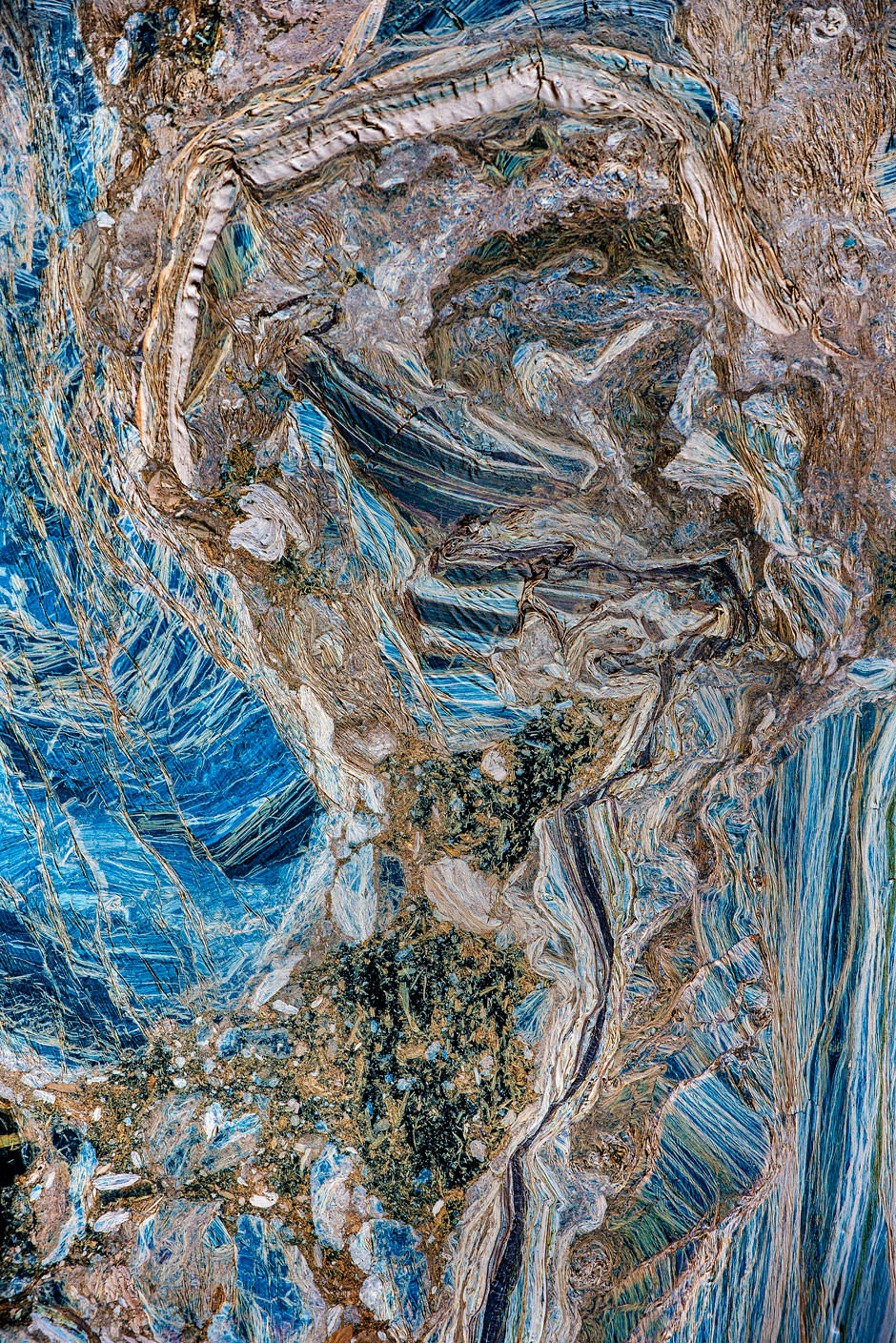

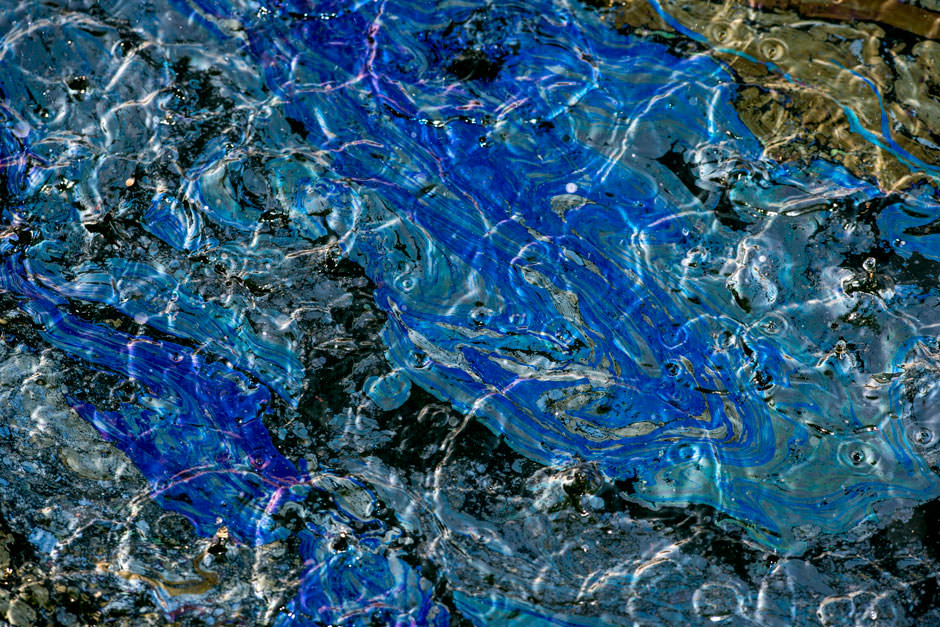

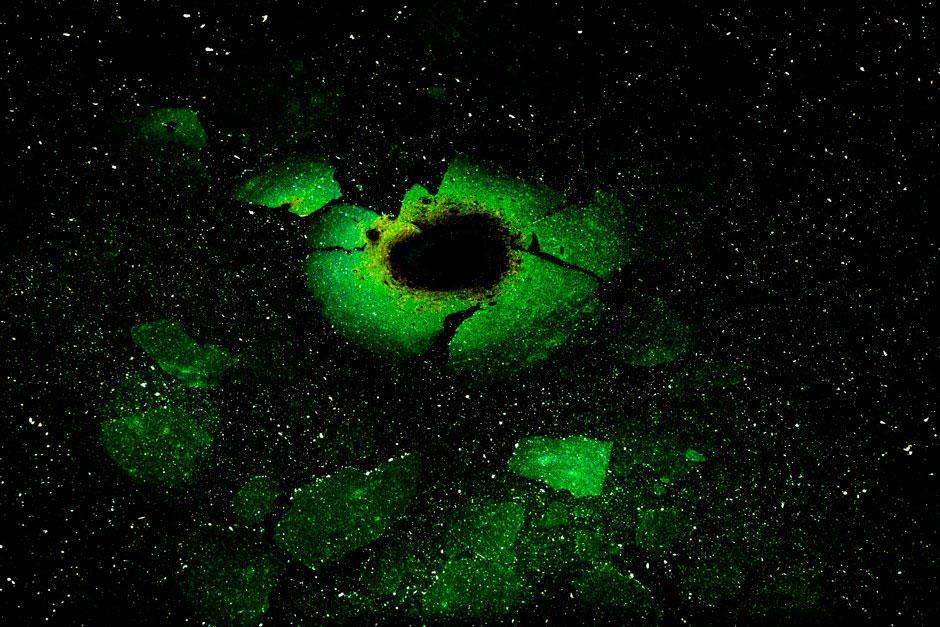

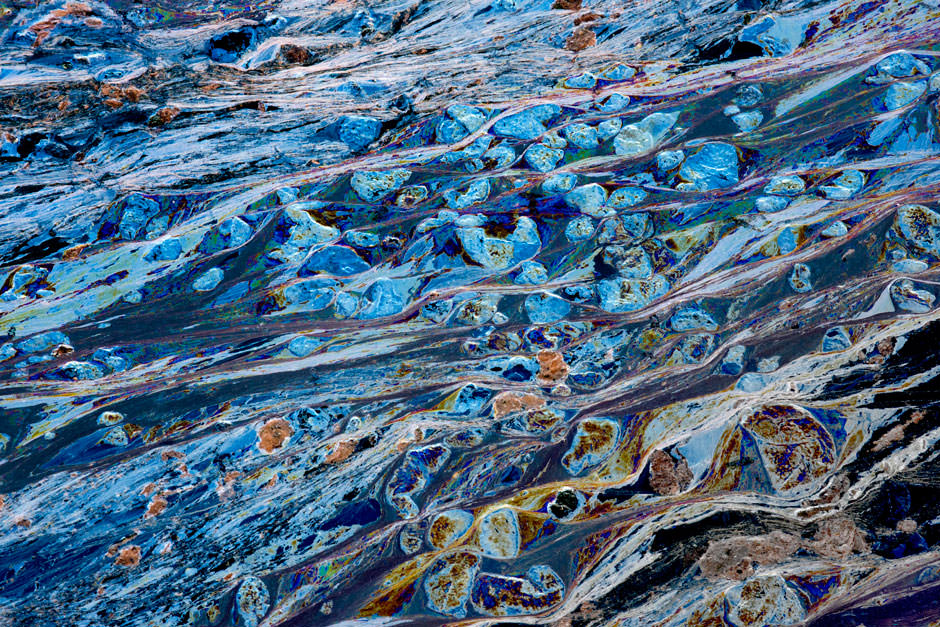

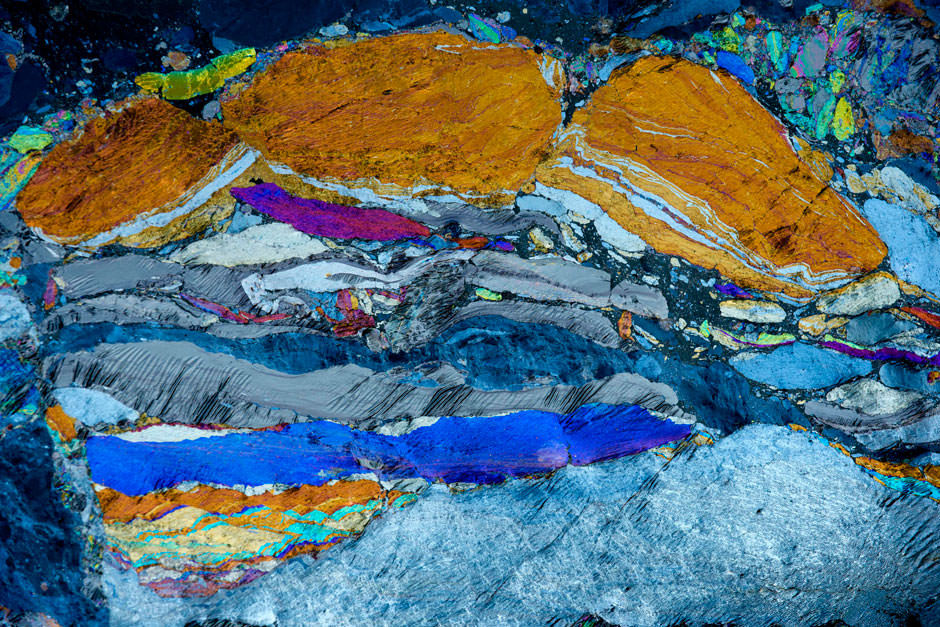

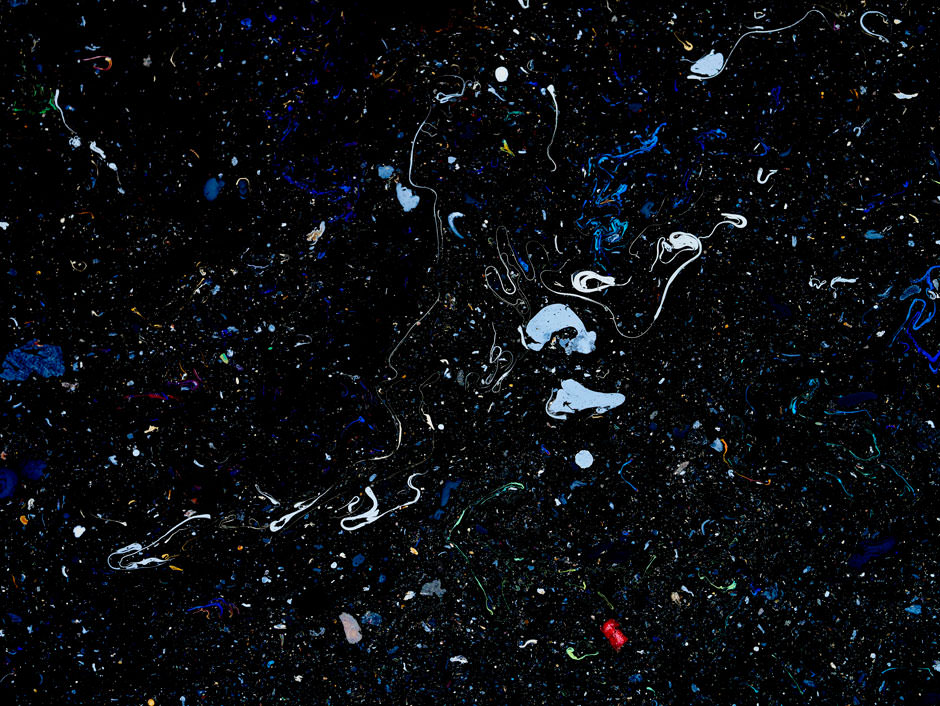

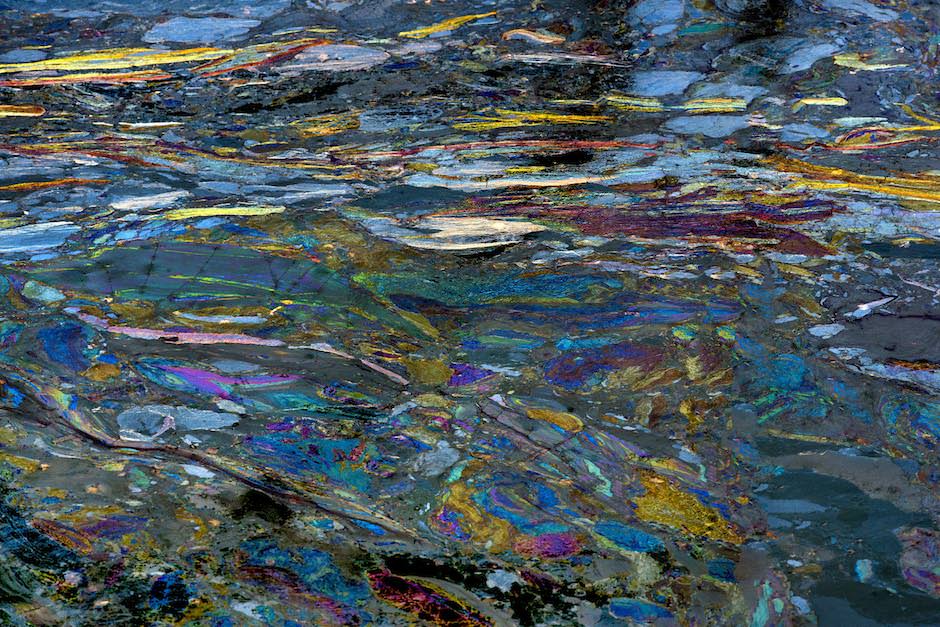

Steven Hirsch is well aware of these facts, but his photographs, as he conceived them, are purely aesthetic. The images are solely concerned with the surface of the water—the gonorrhea, coli, and putida bacteria that cling to one another there in a mosaic of filth. These microorganisms and pathogens create a kind of membrane on the surface of the canal, “like an acetate,” says Hirsch. In the illusions of light and liquid they look like a solid substance, but when, out of curiosity, Hirsch tried to scoop them up they immediately dissolved; even when he transferred water from the canal into a bucket, the microorganisms would disappear.

A native Brooklynite in his mid-sixties, Hirsch emanates a dense, wrestler’s physical power. He would arrive at the canal early on Saturday mornings with a high-mega-pixel camera and a 200 millimeter telephoto lens, trespassing among the derelict factories, hoping not to be seen. He would plant his tripod over the water to get the steadiest, and therefore sharpest, image he could, and start shooting. “My lungs would throb,” he told me. “I’d break out in rashes.”

He printed the images on metallic paper and they are exactly the form of the organisms on the water. Each image is an interpretation of a digital negative. “This isn’t computer-generated art,” said Hirsch. “The highlighted colors are a natural enhancement of what is, the way polish might bring out the color of a scuffed shoe.” Rhode, the largest and most impressive of the prints, has the optical density of paint that has been worked into the paper.

“If I could, I’d make these pictures as large as the canal itself,” said Hirsch. “Or else I’d make them the size of the gallery floor, so that you’d feel as if you were walking on the canal.”

Advertisement

In fact, these photos are a microscopic record of an ecological disaster. One day, the canal will be dredged, the waste capped, and these colorful pathogens, aestheticized or not, will be gone.

“Gowanus: Off The Water’s Surface” is on view at the Lilac Gallery through December 15.