“Everyone who was anyone in the sixteenth-century art world liked Pieter Coecke van Aelst,” writes Anthony Grafton in the Review’s January 8, 2015 issue. Yet until the Metropolitan Museum put on its show “Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry,” he was relatively unknown. Coecke (1502–1550) was a “master who devoted his best talents and energies to tapestries and other collaborative enterprises,” Grafton writes, “and who, for that reason, has never had the fame of the great masters of fresco, portrait, and sculpture.” We present below a series of Coecke’s paintings, drafts, and tapestries with Grafton’s commentary.

—The Editors

This exhibition offers a rich introduction to Coecke’s painting, supported by scholarship that has gradually ascribed more works to him. His panel paintings make skillful use of rich, deeply saturated colors and an impressive range of techniques. Swiftly applied brushstrokes build up the expressive, varied faces of most male characters—especially the caricatured ones of Christ’s tormentors. Women’s faces, by contrast, and that of Jesus are carefully modeled, with smooth flesh tones. Especially impressive is an altarpiece of Christ’s descent from the cross. The interior wings depict Christ’s descent into Limbo and his resurrection, the exterior ones the conversion of Saint Paul, with human and equine bodies painted in grayscale, noble and stark as so many statues.

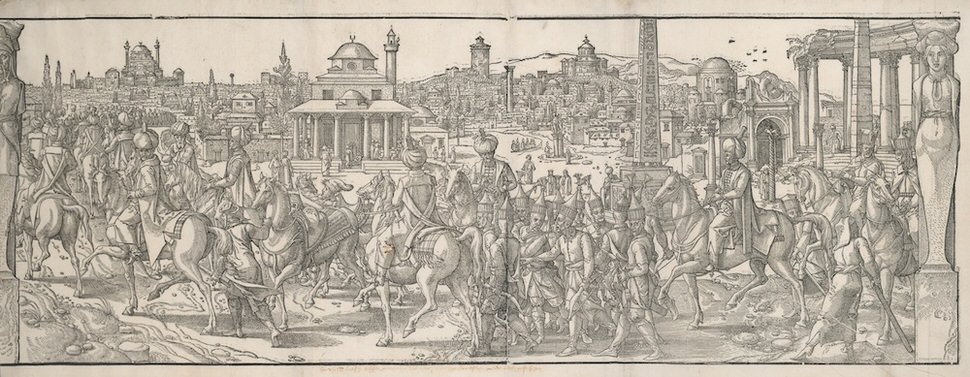

Coecke seems to have planned a series of tapestries on themes of travel and Ottoman life. In the end, though, he created images for a block-cutter, who produced the woodcuts that survive. Here Coecke uses one of his favorite images—a procession—to display Istanbul in all its layered historical complexity. Turbaned horsemen, including Suleiman himself, pass the ruins of the Hippodrome. A caryatid in the right foreground and an obelisk mark the city as ancient. Mosques and minarets in the background show the transformation that has taken place. This brilliant exercise in archaeology and ethnography shows how deeply the ruins of the Christian city interested Coecke. But it also shows that he was just as much captivated by the modern Ottomans he saw and drew, “sitting, squatting, kneeling, riding, lunging forward, and twisting backward,” in the words of the historian Amanda Wunder. Nothing in this revelatory, colorful show reveals Coecke’s powers of observation and invention more vividly than this series of extraordinary black-and-white images.

To walk through galleries hung with Coecke’s tapestries and those of his contemporaries is to relive what it was like to go from room to room in a Renaissance palace or to proceed down one of the aisles of a Renaissance or Baroque church. It’s like strolling in an immense kaleidoscope, as histories and allegories, expressive faces and exotic plants, angels and animals float by.

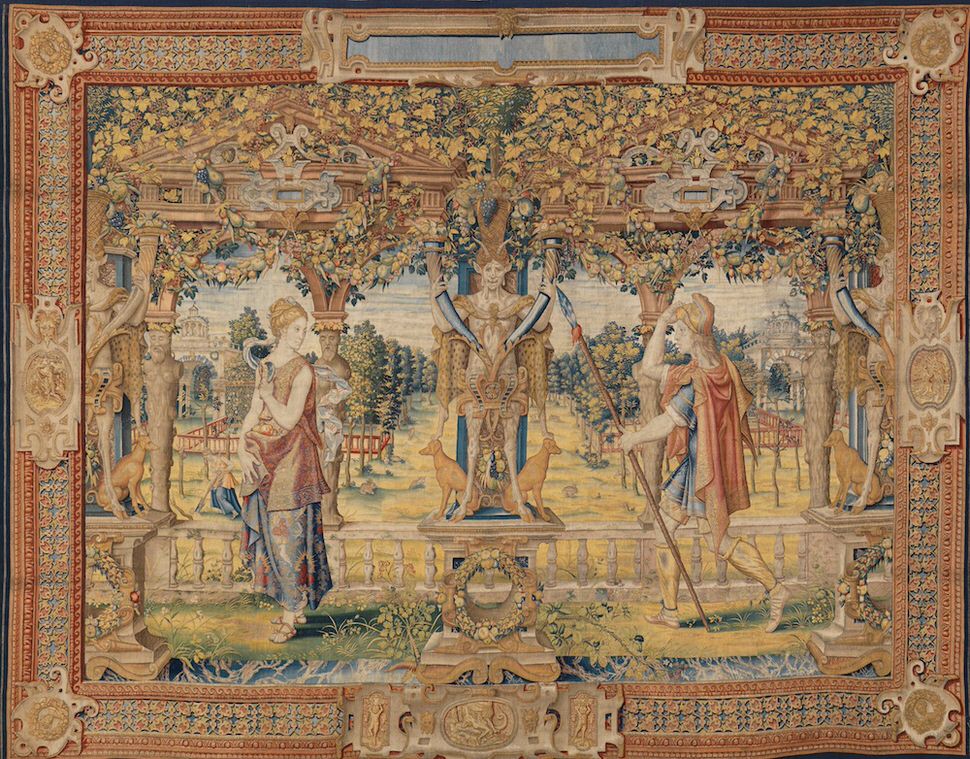

Coecke based one series of tapestries on book 14 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which the Latin poet depicts the wooing of the goddess Pomona by Vertumnus, god of the changing year.

Energetic and indefatigable, Vertumnus disguises himself again and again with a frantic ingenuity that almost turns into slapstick humor. In the exhibition we see him energetically striding toward Pomona, dressed as a herdsman, a soldier, and a fruit picker (in the series as a whole, he also turns up as a harvester, a farmer, a fisherman, and more). Immured in her garden, dressed in simple, elegant clothing and delicate shoes reminiscent of the Ghirlandaio girls in that greatest of Renaissance fantasies, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Pomona stands her ground. Armed with a curved pruning knife, she responds to his approaches with formal gestures that keep him at a respectful distance.

Paul’s conversion does not so much unroll as explode across the whole vast surface of this tapestry. Horses and men, soldiers and angels whirl around the prostrate, imploring figure of the persecutor, suddenly transformed into an apostle. The resurrected Jesus, flanked by angels, dazzles the Romans, as well as the apostle, with his light. Coecke learned much from Raphael, who had designed a tapestry of the conversion of Paul for Brussels makers a generation before. Raphael helped him imagine Christ appearing in glory and use rearing horses to dramatize the scene. But the wild, centrifugal design that Coecke created, in which men and horses seem to be blown out of the picture, even as calm Roman cavalry muster in the background, was his own.

Advertisement

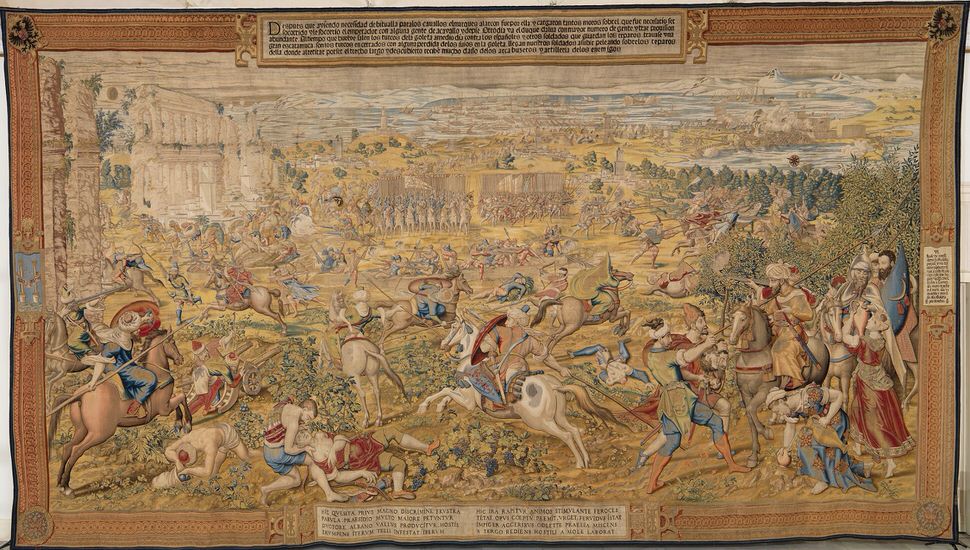

Often Coecke played the part of the impresario, orchestrating all choices of line and color. But he also served, late in life, as an assistant to another artist, Jan Cornelisz. Vermeyen (1500–1559), on a set of tapestries representing the capture of Tunis by Charles V. Vermeyen, a painter favored by the Habsburgs, came with Charles to Tunis in 1535, when the emperor recaptured the city, and made sketches and etchings of what he saw. Proud to a fault, Vermeyen included images of himself sketching in a number of his designs, as well as detailed verbal descriptions of the vantage points from which he had watched.

However, Vermeyen had no experience as a tapestry designer, and he seems to have found it impossible to produce all the sketches needed on the rapid schedule that tapestry making required. Documents show that Coecke took part. Yet they are not absolutely necessary to reveal Coecke’s hand at work in, for example, the wild image of the Spanish soldiers’ Quest for Fodder shown at the Metropolitan. Several individual figures reappear from Coecke’s life of Saint Paul, and even the composition as a whole, with its Turkish horses and men both charging and flying in many directions, seems to echo the wild, apocalyptic Conversion from the same series.

“Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum through January 11.