What happened to the Arab Spring in Syria? Amid a terrible, grinding war now in its fourth year, and a wave of jihadist violence extending from Aleppo and Baghdad to Paris and Brussels, it is sometimes hard to remember that many of the original participants in the uprisings of 2011 aspired to something dramatically different. As with their counterparts in Tunisia and Egypt, the Syrian protesters who took to the streets that spring were neither armed fighters nor militant Islamists; they were university students, civil society activists, and ordinary Syrians who demanded democratic freedoms and an end to the Baathist regime of Bashar al-Assad. And yet, from the outset, Syria—a security state with anti-Western credentials run by the minority Alawite sect—was a complicated case, and many Arab intellectuals, seemingly a natural constituency for the revolutionaries, disagreed about which side to support.

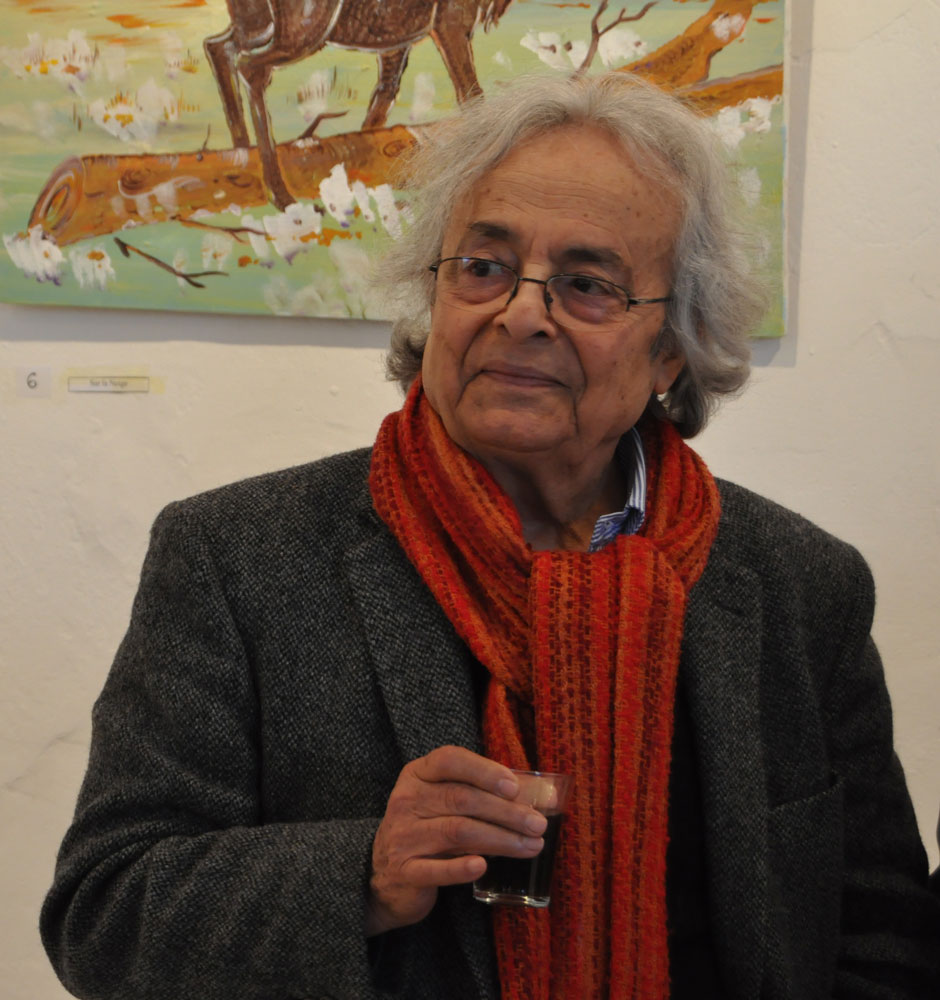

Consider the Syrian-Lebanese poet Adonis, a leading public intellectual in the Middle East and arguably the most influential Arab poet of the twentieth century. Adonis (who was born in Syrian Lattakia but now lives primarily in Paris) greeted the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt with enthusiasm. For him, “the spark of Bouazizi”—the Tunisian fruit vendor whose self-immolation lit the fuse of the revolts—cast a pitiless light on the region’s autocracies and promised a new stage in Arab history, free of the violence and divisions of the past. And yet, when the spark landed in Syria, Adonis’ enthusiasm cooled.

Although his criticism of the regime in Damascus was unambiguous—the Baathists were the latest in a long line of despots who had humiliated, imprisoned, and massacred their subjects—he was notably stingy in his support for the protesters. A central theme of Adonis’ political writings is the need to separate politics from religion, and what concerned him most about Syria was the opposition’s secular bona fides, or lack thereof. “I will never agree to participate in a demonstration that comes out of the mosque,” he wrote. He worried that the protesters were not sufficiently committed to these secular ideas, that “moderate Islam” was a contradiction in terms, and that Syria’s minorities might find life after Assad worse than it was under him.

To his critics, Adonis’ arguments were suspiciously similar to the rhetoric coming from Damascus. As soon as the revolts erupted, the regime warned Syria’s minorities that the only thing standing between them and Sunni revanchism was the Baathist state. Other critics recalled that Adonis had supported the Iranian revolution in 1979—a position he quickly recanted—and accused him of harboring a sectarian agenda (like the ruling family, Adonis hails from a Shia-Alawite background). Four years later, however, Adonis’ guardedness toward the protesters may seem justifiable. The civil war has long since divided on sectarian lines, and the most powerful factions of the opposition have turned out to be Sunni extremists. Was Adonis’ wariness toward the revolution a matter of evasion or was it prudent realism?

One of the challenges to answering this question is our limited understanding of what actually happened during the first months of the uprising, before the opposition became explicitly sectarian and armed by foreign powers. There is little doubt the insurrection arose chiefly in Sunni neighborhoods and rural areas, and a few of the early demonstrators adopted slogans like “Christians to Beirut and Alawis to the grave.” But this doesn’t mean the character and culture of the early opposition was itself sectarian. It may simply reflect the resentment of popular Sunni classes at their exclusion from the Baathist state’s largesse. (Eighty percent of Syria’s Alawis worked for the state at the time of the uprising.) The regime, hoping to solidify its domestic support as well as to convince the West that it was fighting terrorists, certainly did its best to turn the struggle into a sectarian one. It also did its best to force the opposition to become violent—a sure prelude to internationalizing the conflict, since guns cost money.

For an introduction to the ideas and culture of the original Syrian protesters—about which Adonis has curiously little to say—one can scarcely do better than Syria Speaks, an anthology of visual and literary work, most of it from the early days of the uprising. Published by Saqi Books, an independent London-based publishing house of Arab and English-language books, Syria Speaks includes political posters, stencils, cartoons, photography, rap lyrics, fiction and poetry, along with essays tracing the cultural and political background of this work. Much of the material gathered in the book was made in the ambit of Local Coordinating Committees, a loose network of civil society groups at the forefront of the early revolts (and now increasingly beleaguered), which have their roots in leftist opposition groups of the 1970s and 80s. Insofar as the original protests had any kind of organizational structure or political platform, it was mainly provided by the LCCs.

Advertisement

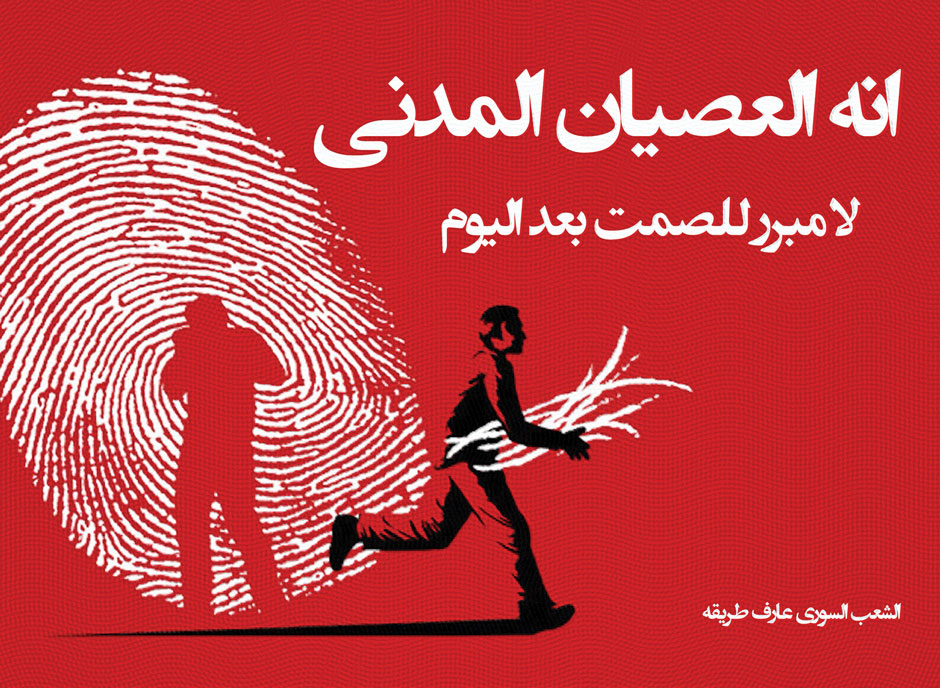

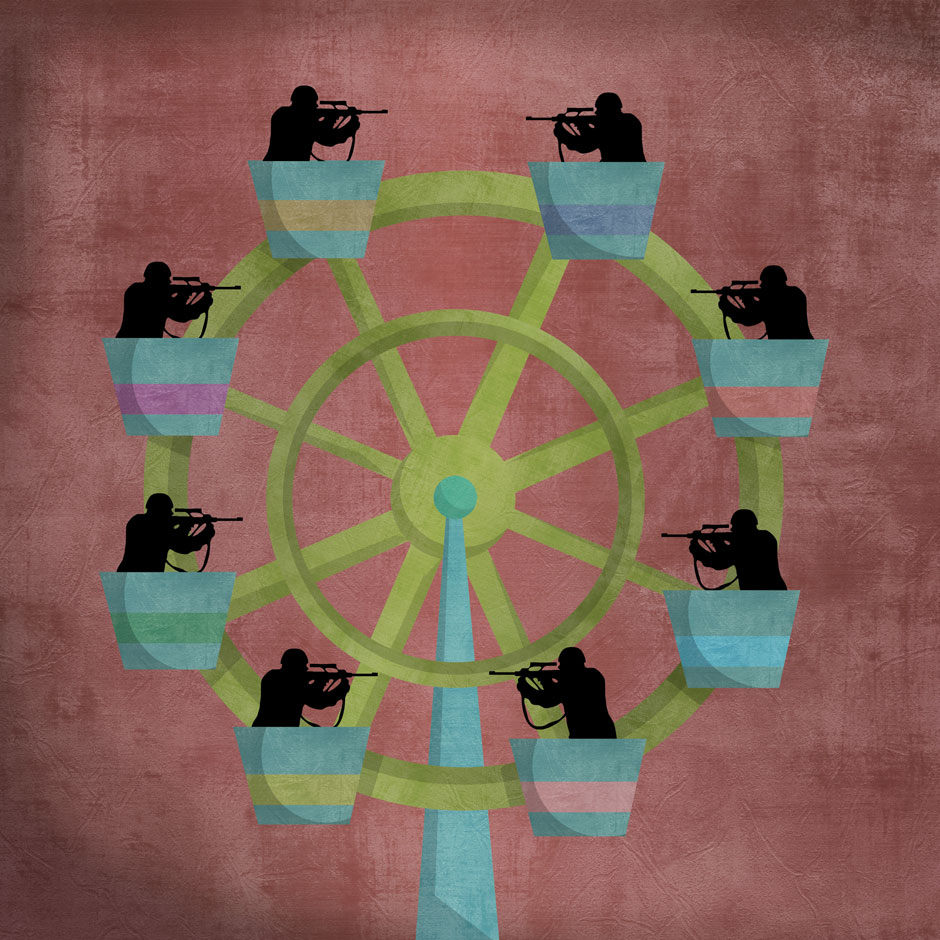

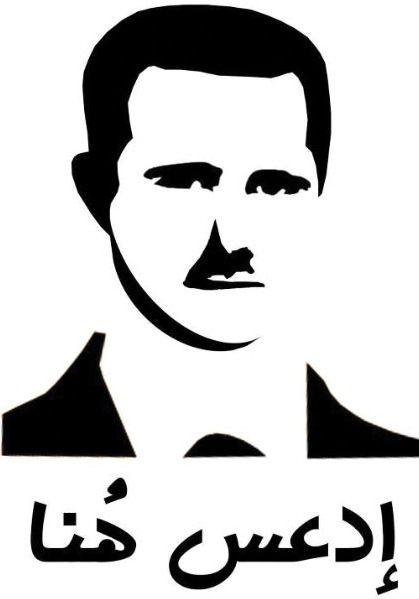

It is striking how closely these works of art model the sort of civil society that Adonis called for. The culture one finds here is pacifist, anti-sectarian, and feminist. The artists do not shy from slogans (sometimes that is the whole point) and so their political commitments are clear. Their posters, for example, call for civil disobedience and deplore the regime’s choice to confront peaceful protesters with guns. Other works depict the results of this policy of repression à l’outrance: martyred children, political prisoners stuffed into cells, a rosary made of human heads. But this is to make the art sound more earnest and less pleasurable than it often is. The best work is blackly humorous, profane, or bluntly insulting—for instance, a stencil by Alaa Ghazal of Bashar al-Assad’s face with the caption, “Step here.”

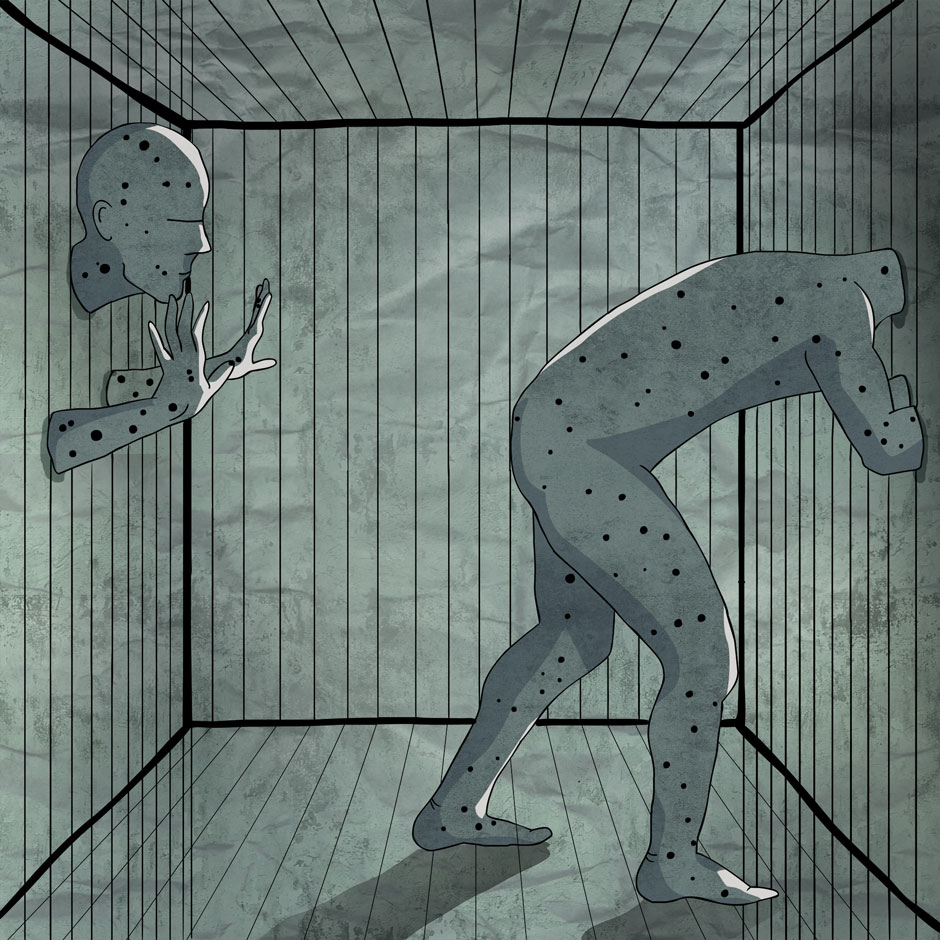

The cheeky humor of Egyptian protesters in Tahrir, often in the form of chanted couplets, was part of what made that revolt so appealing. In Syria, the humor was just as evident, though it was often extremely dark—a kind of mordant satire bordering on hysteria. (Given Syria’s history as a police state, it is no surprise that the Western authors most prized by Syrian readers and writers are those with a taste for the ironical and absurd: Kafka, Orwell, Beckett, Ionesco.) Sulafa Hijazi’s image of a Ferris-wheel with armed men pointing guns at each other, or another of someone pushing his head through one wall of a cage only for it to reenter through another, are terrible emblems of Syria’s predicament, and also undeniably witty. Indeed, it is only the visual wit that makes them bearable to look at.

In other words, the sensibility of these Syrian artists is a mirror image of regime culture. Rather than the slickly monumental imagery of the Baath, the art of the revolutionaries is typically satirical, small-scale, and improvisatorial. In the words of Chad Elias and Zaher Omareen, whose essay on documentary filmmaking in Syria is one of the best in the book, these artists are engaged in “a non-specialized and popular activity.” Whereas government slogans and propaganda fetishize the image of the leader, the revolutionaries often deal with collective or anonymous subjects: women, orphans, dissenters.

The artistic collective, Abounaddara, is a striking example of this tendency. Founded in April 2011, and largely composed of self-taught filmmakers, Abounaddara regularly posts short documentary films (with exceptionally good English subtitles) on its website. The films feature ordinary, usually unnamed Syrians—though there are armed militants as well—talking about their lives before and during the civil war. In its focus on the everyday, including the everyday of violent conflict, the documentaries present a rich and detailed vision of the life that goes on beyond the headlines.

Abounaddara is not the only such collective that emerged during the early revolts. Al-sha‘ab al-suri ‘arif tariqahu (The Syrian People Knows Its Way)—the name suggesting that Syria no longer needs a leader—is a group of graphic designers, calligraphers, and students who put their work online for protestors to print out and carry to demonstrations. The posters borrow from several styles of leftist art, from early Soviet abstraction to the iconography of Palestinian guerillas. Often, the written captions, in elegant typography, play off the stark images. In one poster, a female figure covers her face with a veil, announcing, “I’m going out to demonstrate.” The Arabic verb for “to demonstrate,” atazahar, suggests the process of “appearing” or “becoming visible” (as in the French manifester). So the poster says something more complicated than it may seem to at first blush, something like, “I, a woman, am hiding my private identity, so that I may be seen (anonymously) in a public protest.” One often assumes that slogans have to be simple to be effective, but these posters argue otherwise.

For understandable reasons, much of the work in Syria Speaks is testimonial, blurring the boundary between aesthetics and journalism. Once the regime closed the country to foreign reporters and restricted news to official sources, citizen journalists filled the vacuum with mobile phones and cameras. Much of the work done by the LCCs in the early days of the uprising was to coordinate these informal efforts, in an attempt to keep fellow citizens informed as well as to alert the outside world to what was happening on the ground. Some of the images produced and distributed in this way have more than documentary interest. Lens Young has separate Facebook pages for several Syrian cities—Damascus, Aleppo, Hama, Homs, and others—each one filled with somber and troublingly beautiful scenes of urban destruction, much like photographs of Beirut before and after that civil war. Amid images of entire city blocks of wreckage, are here and there a poignant or horrifying human detail: a family photograph, a decapitated doll. Looking at them, one often thinks of Goya’s Disasters of War and his laconic caption to a scene of fleeing civilians, “Yo lo vi,” “I saw it.”

Advertisement

Many of the literary works in Syria Speaks are also eyewitness accounts of the unfolding drama. The book begins with a diaristic piece by the novelist Samar Yazbek, whose memoir, A Woman in the Crossfire, was one of the earliest books about the revolution to be translated into English. The diary records her meeting with a former regime soldier, who tells her of his decision to defect after a friend is killed by his officer for refusing to rape civilians. Another short piece is by Yara Badr, wife of the imprisoned activist Mazen Darwish, about her own stint in the regime’s prisons:

You don’t need to think hard to remember the dictionary of torture techniques you have been told about—the Flying Carpet, the German Chair, the electric chair, solitary confinement…In the darkness of the cell I could see names and words scribbled on the walls by those who had been brought here before me.

The scholar Miriam Cooke speaks elsewhere in the anthology of “the domination of the [prison] cell over the Syrian imagination,” and indeed Badr’s essay is one of many selections that evoke the claustrophobia of life under the Baath—and, by contrast, the joys of going out into the street to demonstrate. In his poem “Tashriqa: Prayer for Homs,” Faraj Bayrakdar imagines a time when

You are safe from whatever you say or don’t say,

believers and nonbelievers,

all those who lit up the city’s promises

with candles in their fingers.

If one views the essays and artistic statements collected in Syria Speaks as representative of the early uprising, it is impossible not to feel an enormous sense of disappointment about what has happened since, just as it is impossible not to wonder why Adonis didn’t ally himself more wholeheartedly with the artists and revolutionaries one finds here. Perusing the contributor notes at the back of the book, one reads with dismay how many of them are now living abroad (others, of course, do not have that choice), and as of this writing, at least one of them, Mazen Darwish, is in Damascus Central Prison. In their courage, humor, defiance, and occasional moment of optimism, these works already seem to belong to another era—before sectarian war and waves of refugees made the idea of revolution seem quaint.

Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, edited by Malu Halasa, Zaher Omareen, and Nawara Mahfoud, is published by Saqi Books in London.