The following “notes on characters” are drawn from Hilary Mantel’s suggestions to actors in Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies: The Stage Adaptation, by Mike Poulton, published by Picador.

Cardinal Archbishop Thomas Wolsey

You are, arguably, Europe’s greatest statesman and greatest fraud. You are also a kind man, tolerant and patient in an age when these qualities are not necessarily thought virtues.

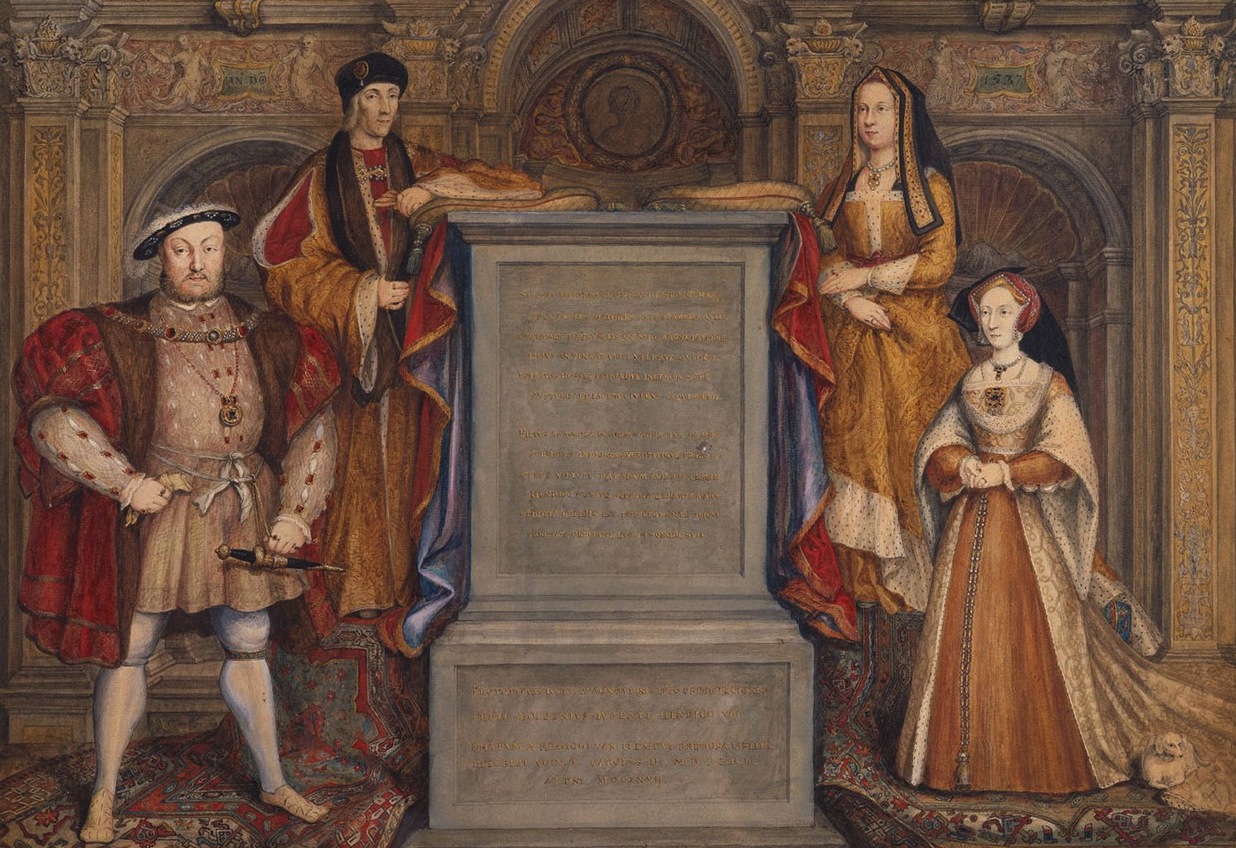

You are not quite the enormous scarlet cardinal of the (posthumous) portrait. You are more splendid than stout, a man of iron constitution who has survived the “sweating sickness” six times. You are a cultured Renaissance prince, as grand and worldly as any Italian cardinal. Renowned for the speed at which you travel, you are capable of an unbroken twelve-hour stint at your desk, “all which season my lord never rose once to piss, nor yet to eat any meat, but continually wrote his letters with his own hands…” Your household observes you with awe, as does the known world. You hope you might be Pope one day, but think it would be more convenient if you could bring the papacy to Whitehall; you wouldn’t want to give up your palaces or your place next to your own monarch, and anyway you could probably run Christendom in your spare time.

When Henry VIII came to the throne you were ready to take much of the burden off the young back, and the Prince was glad to let you carry it. You have real esteem and affection for the young Henry, and he loves you for your personal warmth as well as your unique abilities. You are not only Lord Chancellor but the Pope’s permanent legate in England. So your concentration of power, foreign and domestic, lay and clerical, is probably greater than that wielded by any individual in English history, kings and queens excepted. You are so sure of yourself, that your unraveling is total and unexpected and tragic.

When Henry first asks for an annulment of his marriage, you are confident that you will be able to secure it. But the politics of Europe turn against you, and you find yourself trapped, faced with an impatient, angry monarch, and between two women who hate you: Katherine of Aragon, who has always been jealous of your influence with the King, and Anne Boleyn, who resents you because, before the King set his heart on her, you frustrated the good marriage she intended to make. You are astonished by the extent of the enmity you have aroused (or at least, you say you are) and, like everyone else, you are baffled by the King’s conduct; he wants you banished, then he offers to make peace, then he wants you banished.

No one is capable of assuming your role in Government, and Henry quickly learns this. When you are packed off to the north of England, you do not behave like a man in disgrace. You draw both the gentry and the ordinary people into your orbit, and soon you are living like a great prince again, and writing to the powers of Europe to ask them to help you regain your status. When these letters are intercepted, you are arrested and set out to London to face treason charges.

Soon after your arrest you have what sounds like a heart attack, followed by an intestinal crisis which leads to catastrophic bleeding. There are rumors that you have poisoned yourself. You are forced to continue the journey, and die at Leicester Abbey. Your body is shown to the town worthies so that no one can claim that you have survived and escaped, to set up opposition to Henry in Europe. It is the kind of precaution usually taken for a prince. Even dead, you spook your opponents. Your tomb—which you have been designing for twenty years, with the help of Florentine artists—is taken apart bit by bit and elements find their way all over Europe. At St. Paul’s, Lord Nelson occupies your marble sarcophagus, rattling around like a dried pea.

Anne Boleyn

You do not have six fingers. The extra digit is added long after your death by Jesuit propaganda. But in your lifetime you are the focus of every lurid story that the imagination of Europe can dream up. From the moment you enter public consciousness, you carry the projections of everyone who is afraid of sex or ashamed of it. You will never be loved by the English people, who want a proper, royal Queen like Katherine, and who don’t like change of any sort. Does that matter? Not really. What Henry’s inner circle thinks of you matters far more. But do you realize this? Reputation management is not your strong point. Charm only thinly disguises your will to win.

Advertisement

You come to the English Court in your early twenties, but you are in your late twenties before you catch Henry’s attention, and ours in the plays. Your contemporaries did not think you were pretty because they admired pink-and-white blonde beauty, and you (judging by their descriptions) were dark and slender. This difference becomes part of your distinction. It’s your vitality that draws the eye. You sing beautifully and dance whenever you can. You are the leader of fashion at the Court, before you become Queen.

When the King makes his first approaches you are wary because you don’t intend to be a discarded mistress, like your sister Mary. You make him keep his distance and work hard for a smile. To think that you, a knight’s daughter, could replace the Queen of England is an idea so audacious that it takes a while for the rest of Europe to catch up with it. It’s assumed that, once Henry’s divorce comes through, he will marry a French princess. You are Wolsey’s downfall; for a long time, though he remembers you exist, he doesn’t know you’re important to the King. As far as he is concerned, he has finished his dealings with you when he makes Harry Percy reject you. There was a time when the King told Wolsey everything. But since you came along, that age has passed.

Your campaign to be Queen is fought with patience and cunning. Saying “no” to Henry is a profitable business and you are made Marquise of Pembroke. There is a point when, after you feel Henry has committed himself to you, you’d probably be willing to go to bed with him; but by that time, he’s intent on remaining apart until you are married. He says you have promised him a son, and he wants to be right with his conscience and with God. Any child you have must be born within your marriage. You marry secretly in Calais, at the end of 1532, and a few weeks later, with no fuss, on English soil. Elizabeth is born the September following. Though Henry is disappointed not to have a boy, he doesn’t (as myth suggests) turn against you. He is glad to have a healthy child after losing so many, and confident of a boy next time.

Are you really a religious woman, a convinced reformer? No one will ever know. It’s probable that you picked up your ideas at the French Court, where the intellectual as well as the moral climate is freer. There’s nothing to gain for you in being a faithful daughter of Rome. The texts you put Henry’s way are self-serving, in that they suggest the subject should be obedient to the secular ruler, not to the Pope. But you go to some trouble to protect and promote evangelicals. “My bishops,” as you call them, are your war leaders against the old order.

After Elizabeth’s birth you miscarry at least one, maybe two children. Henry feels he has staked everything on a marriage that, despite his best efforts, no one in Europe recognizes. You start to quarrel. Ambassador Chapuys gleefully retails each public row in dispatches. Cromwell warns the Ambassador not to make too much of it; you have always quarreled and made up. But, unlike Katherine, you don’t take it quietly when Henry looks at other women. That he would become interested in someone as mousy as Jane Seymour seems like an insult.

At some point on the summer progress of 1535 you become pregnant again. At the end of January, on the day of Katherine’s funeral, you lose the child, a boy. (Contrary to the myth that’s taken hold, there is no evidence that the child was abnormal.) In the opinion of Ambassador Chapuys: “She has miscarried of her savior.” You celebrated when you heard of Katherine’s death, but it is not really good news for you. In the eyes of Catholic Europe, the King is now a widower, and free.

You are now in trouble. You are right in thinking you are surrounded by enemies. Nothing you could do would ever reconcile the old nobility to your status, and the tactless and noisy rise of your family has cut across many established interests. Katherine’s old friends and supporters are beginning to conspire in corners, and make overtures to Cromwell. Will he support the restoration of the Princess Mary to the succession, if they back him in a coup against you?

Advertisement

When Henry decides he wants to be free, the idea is to nullify the marriage, not to kill you. The canon lawyers go into a huddle with Cromwell. Then the whole business is accelerated and becomes public, because in late April 1536 you quarrel with Henry Norris; and afterwards you visibly panic, giving the impression of a woman who has something to hide. Everything you say is keenly noted and carried to the King, who immediately concludes you have been unfaithful to him. Cromwell is talking to your ladies-in-waiting. It’s possible that, even at this stage, he is not sure how he will bring the matter to a crisis. But when you are arrested you break down and talk wildly, supplying yourself the material for the charges against you.

By the time of your trial and your death you have collected yourself and are, according to Cromwell, “brave as a lion.”

Thomas Cromwell

Your date of birth is unknown (nobody noticed) but you are in your forties during the action of these plays and about fifty at the time of Anne Boleyn’s fall. Your father was a blacksmith and brewer, the neighbor from Hell to the townsfolk of Putney, a heavy drinker and prone to violence. Your mother’s name is unknown. You don’t say much about your past, but you tell Thomas Cranmer, “I was a ruffian in my youth.” Whatever this statement reveals or conceals, you have a lifelong sympathy with young men who have veered off-course.

At about the age of fifteen you vanish abroad. You join the French Army and speak French. You go into the household of a Florentine banker and speak Italian. You set up in the wool trade in Antwerp and speak Flemish and also Spanish, the language of the occupying power. You come home to London: and who are you? You’re a man who speaks the language of the occupying power. Traces of the blacksmith’s boy are almost invisible. The rough diamond is polished. You have seen at least one battle at close quarters, a calamitous defeat for your side; it’s enough to turn you against war. You have seen childhood poverty and modest prosperity and you know all about what money can buy. You have learned from every situation you have been in. You are flexible, pragmatic and shrewd, with a streak of sardonic humor. You are widely read, understand poetry and art. Somewhere on the road you found God. Your exact views (like much about you) remain unknown. But you are a reformer and your religious feelings are strong and genuine.

On the other hand… you’re quite prepared to torture someone, if reasons of State demand it and the King agrees. (You probably don’t torture Mark Smeaton.) You are a natural arbitrator and negotiator, preferring a settlement to a fight, but if pushed—as you are by the Boleyns in 1536—you are ingenious and ruthless.

You and Wolsey are close. When he falls from favor, you are the only person who remains completely loyal. Much about you is equivocal, but this is not. You get yourself a seat in the Commons, and through his long winter in exile at Esher you attend every sitting, trying to talk out the charges that have been brought against him. You expend effort and your own money. When he goes north, you remain in London looking after his interests. You warn him that the way to survive is to retire into private life. But, though he listens to you on most matters, in this instance he doesn’t. His loss is devastating to you. Ten years later, you are still defending his good name: though Wolsey, a corrupt papist, ought to have been everything you hate.

You first come to Henry’s notice when Wolsey’s empire has to be pulled apart. Henry does not think he has many true friends and is touched by your loyalty to the Cardinal. You become his unofficial adviser long before you are sworn in to the Council. Your promotion causes predictable outrage, not just because of your humble background but because you are still known as the Cardinal’s man. To save everyone embarrassment, it is proposed you adopt a coat of arms from another, more respectable family called Cromwell. But you refuse. You are not ashamed of your background; you don’t talk about it, but you don’t conceal it either. In fact, you never apologize, and never explain. (And when you get your own coat of arms, you incorporate a motif from Wolsey’s arms, so that it flies in the faces of his old enemies for years to come.)

Your household at Austin Friars, as you progress in the King’s service, is transformed, extended, rebuilt, into a great ministerial household, a power center, cosmopolitan and full of young men who are there to gain promotion. You take on the people written off elsewhere, the wild boys who are on everybody’s wrong side, and make them into useful workers. You are an administrative genius, able to plan and accomplish in weeks what would take other people years. You are good at delegating and your instructions are so precise that it’s difficult to make a mistake. You extend the secretary’s role so that it covers most of the business of State; you know what happens in every department of Government.

Your ideas are startlingly radical, but mostly they are beaten off by a conservative Parliament. At the center of a vast network of patronage, you have a steady tendency to grow rich. You are generous with your money, a patron of artists, writers and scholars, and of your own troupe of actors, “Lord Cromwell’s Men.” The kitchen at Austin Friars feeds two hundred poor Londoners daily. All the same, you are a focus of resentment. The aristocracy don’t like you on principle, and the ordinary people don’t like you either. In the opinion of the era, there’s something unnatural about what you’ve achieved. In the north they think you’re a sorcerer.

Much of your myth is ill-founded. You do not control a vast spy network. You do not throw elderly monks into the road; in fact, you give them pensions. You are not the dour man of Holbein’s portrait but (witnesses say) lively, witty, and eloquent. Your weakness is that you do not head up a faction or an interest group and have no power base of your own; you depend completely on the King’s favor. You are resented by the old nobility, and you are destroyed when your two implacable enemies, Norfolk and Gardiner, manage to make common cause. But by then, you have reshaped England, and even the reign of the furiously papist Mary can’t undo your work; you have given too many people a stake in your remodeled society.

The Calais Executioner

For a believing Christian of the sixteenth century, the most important moment of life is the moment when we leave it. We leave with our sins absolved, from a prolonged deathbed with family and a confessor at hand: or suddenly from the battlefield, in the midst of our anger and pride. We are struck down by disease, like one of the victims of the era’s epidemics, “merry at breakfast, dead by dinner.” Or perhaps we fall foul of the law. The procedures for judicial killing are rule-bound and fixed, like the rites of the church. As on a deathbed, the sufferer must show contrition. In any speech to the crowd, he or she must accept the sentence, and praise the king. When the priest has done his part he steps aside and you, the headsman, are the focus of all eyes.

For the client of the Calais headsman, severance occurs within the blink of an eye, between two pulse-beats. You depend on your victim’s cooperation; to receive the killing stroke, he or she must kneel upright, in a posture of attentive prayer: remaining, with the courage instilled by a lifetime of self-discipline, rigid on the brink of eternity. Apprehensive about the pain, the Queen of England asks the Constable of the Tower how it will be. He tells her, “There should be no pain, it is so subtle.” She puts her hand to her throat: “I have only a little neck.”

She must not be frightened, she must not be alarmed. She must not know that you are her fate. As part of your contract, an allowance is made to purchase the clothes suitable for a gentleman, so that to the Queen you will appear just another witness in the crowd. (She has seen you before, perhaps, but does not quite recall; you, or some man like you, staring; she is used to that.) Only at the last second will she recognize you, as you kneel to ask her pardon before her blindfold cuts out the light. She must not know the angle of her death, its path through thin air: you will call out, “Bring me the sword!” and her head will whip around, and you will not be where she thinks you are, and she will be dead.

A sword, a good sword, is a precious and beautiful possession, and a sword dedicated to a single purpose is a sacred object. You are proud of the weapon and proud of your craft, and proud to know that the King of England has heard of both. When the summons comes, and you embark to cross the Narrow Sea, you mean to burnish your reputation. On the day, your performance is immaculate. Your fee is £23.6.8d. The blade of your sword is incised with the words of a prayer.

The Royal Shakespeare Company production of Wolf Hall: Parts One and Two, directed by Jeremy Herrin, is now in previews at the Winter Garden Theater in New York.