On Wednesday, a group of thirty protesters staged a sit-in inside the Mobile, Alabama office of Republican Senator Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III. They delivered an ultimatum: they would stay until Senator Sessions, President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee for attorney general of the United States, declined the nomination. Around 7 PM, police arrested six people for refusing to leave. All were from the NAACP—including its president, Cornell W. Brooks.

In a statement, Brooks explained why the NAACP believes Sessions is the wrong person for the job. “Senator Sessions has callously ignored the reality of voter suppression but zealously prosecuted innocent civil rights leaders on trumped-up charges of voter fraud,” he said. “As an opponent of the vote, he can’t be trusted to be the chief law enforcement officer for voting rights.”

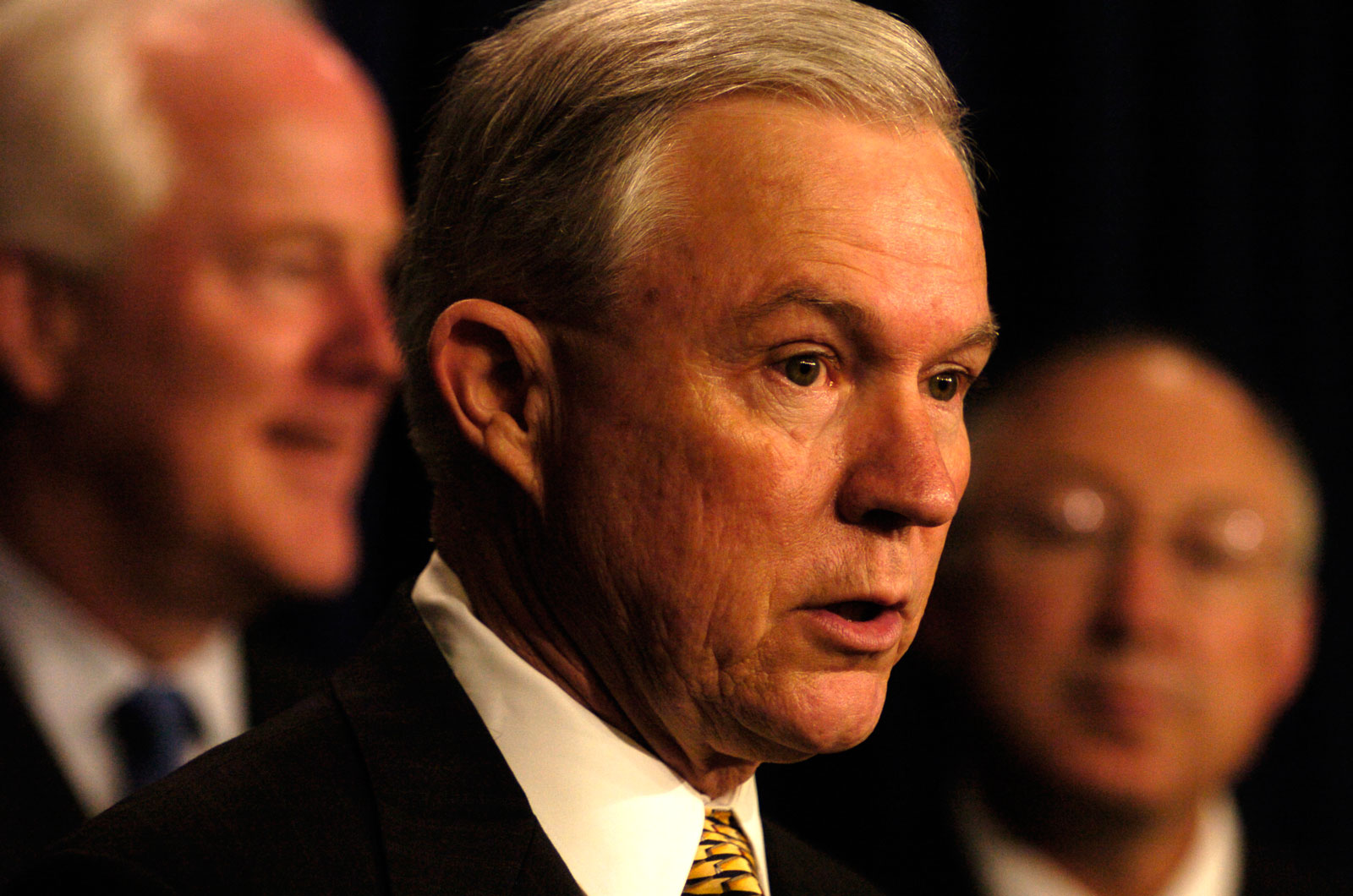

It’s no coincidence that the NAACP’s act of civil disobedience recalls the civil rights years. Sessions himself seems a throwback to that era—and not on the side of the heroes. And for the NAACP, a throwback is not what we need now, when racial tensions around policing are high, hate crimes have dramatically increased, and white supremacists have been emboldened by the election of Donald Trump. Throughout his career, Sessions has shown insensitivity, if not outright hostility, to the interests not only of African-Americans, but of Muslims, gays and lesbians, women, and immigrants as well. The attorney general of the United States is charged with enforcing the law equally for all, and with overseeing the enforcement of the civil rights laws that protect those most vulnerable. Is Jeff Sessions the right man for the job?

Cornell Brooks will be testifying at Sessions’s confirmation hearing, which will be conducted Tuesday and Wednesday of this week. I will also be testifying, on behalf of the ACLU. As a matter of longstanding policy, the ACLU does not take positions supporting or opposing nominees for office, and as a result it rarely testifies in confirmation hearings. But we are sufficiently concerned about Sessions’s record that we have elected to depart from our usual practice and speak out—not to oppose the nomination, but to insist that the many questions about Sessions’s record must be answered before the Senate votes on his nomination. Here are five:

1. Does Sessions believe that all Americans, regardless of race, should have an equal right to vote?

The last time Sessions stood before the Senate Judiciary Committee—in 1986, when President Ronald Reagain nominated him to be a federal district court judge—this question was fatal. The hearing was dominated by allegations that Sessions had called a black colleague “boy,” and told that same black colleague that he thought the Ku Klux Klan was okay until he learned that some of them smoked marijuana. The hearing also focused on Sessions’s vigorous prosecution of three civil rights activists in Alabama one year earlier for helping African-Americans to vote. The lead defendant, Albert Turner, was a civil rights icon who worked for the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, marched with John Lewis across the bridge at Selma, and earned the nickname “Mr. Voter Registration” for registering black voters after Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1964. Because of the work of Turner and others like him, the number of African-Americans voting in Alabama rose from near zero in 1965 to 70,000 in 1982, helping elect over one hundred black officials.

For some, opening the vote to African-Americans for the first time in Alabama was something to celebrate. For Sessions, it was a cause for concern. He launched an aggressive and intrusive investigation of absentee voting only in districts where black voting had increased. As a new report by the Brennan Center for Justice observes, quoting from a 1985 Chicago Tribune investigation of voter disenfranchisement in Alabama:

Sessions and his counterpart in the Northern District of Alabama began investigating alleged absentee ballot fraud by black civil-rights activists…. “Hundreds of witnesses, most of them black, [were] interviewed about vote fraud.” Meanwhile, at the same time, the Department of Justice refused to investigate complaints that white politicians solicited longtime nonresidents to submit absentee ballots in local elections. In Perry County, where the Marion Three had collected absentee ballots, the FBI went to the doors of hundreds of black citizens, flashing their badges, asking how they had voted, whether they had received help from black civil-rights activists, whether they could read and write, and why they had voted absentee. The chairman of the National Council of Black State Legislators called the tactics an effort “to disenfranchise blacks who are finally gaining political power in the South.”

Sessions then threw the book at Turner and the other two defendants, who faced more than one hundred years in prison for allegedly violating the Voting Rights Act. According to former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick, who represented one of the defendants, Sessions maintained that it was a federal crime to advise people on how to vote. It is not, of course. Indeed, advising people on how to vote is the whole point of electoral campaigns. The judge dismissed more than fifty counts before trial, rejecting Sessions’s novel and anti-democratic theory. When Sessions proceeded to trial on the remaining counts, the jury of seven African-Americans and five whites acquitted the defendants on all charges in short order.

Advertisement

This case was so troubling during Sessions’s 1986 confirmation hearing that the Judiciary Committee, in a bipartisan vote, declined to send Sessions’s nomination to the Senate floor, and the nomination was withdrawn. In the thirty years since, the questions raised at the 1986 hearing have never been satisfactorily answered.

2. How does Sessions defend his record on voting rights laws in the twenty years he has been a Senator for Alabama?

As the nation’s top law enforcement official, Sessions will determine how vigorously the Department of Justice enforces the nation’s voting rights laws. But as a Senator, he has opposed restoring felons’ voting rights even after they have done their time, and even though felon disenfranchisement disproportionately excludes African Americans from the ballot box. Notwithstanding the widely noted lack of virtually any evidence of voter impersonation fraud, Sessions has defended restrictive voter ID laws, which also disproportionately bar minority and poor voters, who are less likely to have the official forms of identification required. The real reason for voter ID laws, which are supported almost exclusively by Republicans, is to disenfranchise voters who are more likely to vote for Democrats; Sessions has been an eager cheerleader in this brazenly partisan effort to suppress the other side’s vote.

In 2006, Sessions went along with the unanimous vote of his Senate colleagues to extend the Voting Rights Act for another twenty-five years, although he then proceeded to undermine the legislation by signing on to a section of a Senate report drafted by Republicans after the law was approved. And more recently, he called the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which gutted the Act’s most important enforcement provision, “good news…for the South.” The decision, which lifted an obligation on states with a history of voting discrimination to clear changes in voting laws with the Justice Department, spurred renewed efforts in several of those states to suppress voting by minorities.In North Carolina, for example, a federal appeals court found that the state legislature intentionally discriminated against black voters in a series of voting changes it took up the day after Shelby County was decided. Sessions has expressed no concern whatsoever about those efforts.

3. Why has Sessions so often opposed efforts to protect the rights of women and gays and lesbians?

The Justice Department is responsible for investigating and prosecuting hate crimes and civil rights violations, and for enforcing the Violence Against Women Act and the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act. Yet Sessions’s record reveals a fundamental failure to take seriously—or in some instances, even to recognize—discrimination against women and gays and lesbians. When asked whether Donald Trump’s infamous tape-recorded statement that as a celebrity, he can “grab women by the pussy,“ described behavior that would constitute sexual assault, Sessions replied, “I don’t characterize that as a sexual assault. I think that’s a stretch.” If grabbing a women by her genitals is not sexual assault in Sessions’s mind, what would be? Sessions also voted against reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, and has been outspoken in calling a woman’s constitutionally protected choice to terminate a pregnancy “murder.” With views like these, can he be trusted to enforce laws protecting women from sexual violence, and ensuring their access to abortion clinics?

Sessions’s record with respect to gays and lesbians is even worse. He voted in favor of a constitutional ban on marriage equality. He voted against the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” a repeal favored by the military because sexual orientation has no relevance to military service. He stated in 2009 that filling a Supreme Court vacancy with an openly gay nominee “would be a big concern that the American people might feel—might feel uneasy about.” He voted against extending anti-discrimination employment law to gays and lesbians. And he even voted against the Matthew Shepard Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which extended the existing federal hate crimes law to crimes motivated by gender, sexual orientation, or disability. Perhaps most disturbingly, he argued that the law was unnecessary because women and LGBTQ individuals do not face serious discrimination, stating that: “today I am not sure women or people with different sexual orientations face that kind of discrimination. I just don’t see it.”

Advertisement

4. Is Sessions prepared to treat all religions equally, and to honor the separation of church and state?

When Donald Trump in December 2015 called for a ban on all Muslims entering the United States, a blatantly unconstitutional proposal, Senator Patrick Leahy introduced a non-binding resolution in the Senate to clarify that the Senate opposed the use of religious tests for immigration decisions. The resolution did no more than underscore what the Constitution already requires. The Establishment Clause forbids the government from taking action that either favors or disfavors any specific religion. Yet Sessions was one of only four Senators to oppose the amendment, and he spoke out at length against it, asserting that immigration officials should be free to interrogate immigrants about their religious beliefs, and to exclude those with unacceptable religious views.

Sessions has also called Islam, one of the largest religions in the world, a faith held by millions of law-abiding Americans, a “toxic ideology.” If he had labeled Christianity a “toxic ideology,” is there any doubt that he would be disqualified for this post? On Christianity, however, Sessions takes a very different view. In 1998, he introduced a resolution in the Senate supporting the unconstitutional action of Alabama judge Roy Moore in displaying the Ten Commandments in his courtroom. A federal court ruled that Judge Moore’s display violated the Establishment Clause. Some years later, an Alabama judicial ethics body expelled then-Chief Justice Moore from office for defying a federal court order to remove a monument to the Ten Commandments from the courthouse.

5. Can Senator Sessions be an attorney general for all the people?

Our nation is riven by a deep partisan divide. Trust in government has fallen to new lows. Intolerance abounds. It is therefore especially important that the person chosen to enforce our laws be sensitive to the rights of all Americans, and be cognizant of the particular need to protect the civil rights and civil liberties of the most vulnerable. Is Senator Sessions that person? The Senate should not confirm him until he can provide satisfying answers to all of these questions.