In 2001, the French-Canadian artist Guy Delisle spent several months living in North Korea while working for an animation studio, SEK— the Scientific Educational Film Studio of Korea. Delisle, then thirty-five and a seasoned animator, had traveled to Pyongyang on a work visa for a French film animation company; the SEK is used to attract foreign currency, most of it French, as he explains. His graphic memoir of that time, Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea (translated into English in 2005), was a rare first-hand look at life inside North Korea and became an international best seller.

Pyongyang opens with Delisle’s interrogation at the Pyongyang airport, as he struggles to explain the things he has dared to bring into the country: a copy of George Orwell’s 1984 and an Aphex Twin CD (he makes it through with both). In minimalist and black-and-white drawings, with a light touch and wry observations, Delisle gives a fascinating account of his encounters with North Korean culture, from the trials of basic transportation to the scores of laboring “volunteers” to awkward interactions at sites like the Museum of Imperial Occupation and the International Friendship Exhibition—and of his battles with the minders who strenuously tried to control those encounters. He draws himself as an appealing buffoon, with a stylized blocky head and angular nose; his readers learn as he does.

Pyongyang was such a success that Delisle turned to comics full time. He became perhaps the best-known face of what might be called the comics travelogue, now a flourishing genre, and published three further in the same style featuring his observations about living in foreign cities: Shenzhen: A Travelogue from China (2006), Burma Chronicles (2008), and Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City (2012). The “chronicles” books are structured by a series of vignettes; Delisle and his wife Nadège, a Doctors Without Borders administrator, have two children, and light domestic hijinks become part of his accounts. (Delisle also published three books of humor comics for parents, the first of which is called A User’s Guide to Neglectful Parenting.) Yet even compared to the much longer Jerusalem, Pyongyang remained Delisle’s most substantive and insightful book.

In the realm of nonfiction comics, much has happened since Pyongyang first appeared. Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, a breathtaking family memoir, arrived a year later in 2006. Fun Home is one of the most significant graphic works of the twenty-first century, showing, as did Art Spiegelman’s Maus, how comics can play with place and chronology in order to express history and inheritance across generations. And there have been many sophisticated comics biographies and autobiographies, such as Lauren Redniss’s experimental biography of the Curies, Radioactive, and John Lewis’s series March, a collaborative effort with a congressional aide and an illustrator about Lewis’s years growing up in the civil rights movement, the third volume of which won the National Book Award last year for young people’s literature (though in its savvy interplay of words and images to deliver historical detail, much of it quite dark, Lewis’s book transcends that categorization).

Perhaps most importantly, there has been the rise of comics journalism—reporting in comics form. Joe Sacco published in 2009 his monumental work Footnotes in Gaza, an investigation of the two largest massacres of Palestinians on Palestinian soil, which took place in the wake of the Suez Canal crisis in 1956. As in his earlier book about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the groundbreaking Palestine, and his works about the Yugoslav wars, Safe Area Goražde and The Fixer, Sacco combined meticulous research with moving visualizations of the people he interviewed, and their testimony. Sacco uncovered archives in Israel that had never before been translated, along with important UN documents relating, ambiguously, to the circumstances precipitating the killings. Further, he tracked down and interviewed as many survivors of both of the massacres as he could find, drawing their faces in both the present and the past, and illustrating their stories.

Although Delisle is often mentioned together with Sacco as part of the recent explosion of nonfiction comics, and, like Sacco, features himself as a character in his stories, his work is in a very different key. Sacco’s books are painful in a way Delisle’s rarely are. Delisle’s comics are about politics, and often depict repressive regimes; reading censored magazines upon arriving in Myanmar in Burma Chronicles, frustrated with so many missing pages, it suddenly dawns on him: “Oh right! I almost forgot. We’re under dictatorship here.” But they rarely feel invested in a larger ethical project—representing the particular lives of people who have been ignored in the West—the way Sacco’s do.

Advertisement

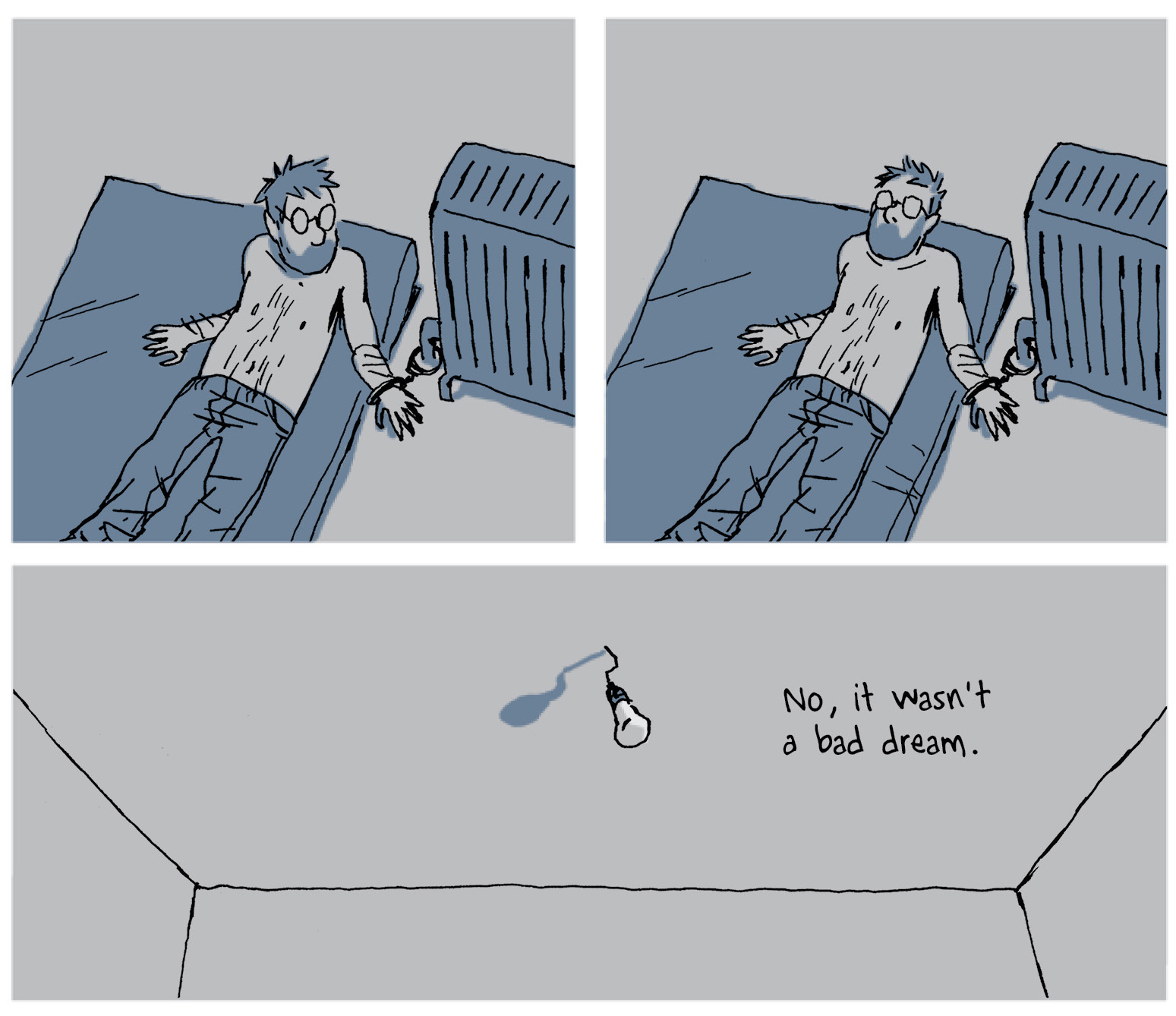

Delisle’s new book, Hostage, is his best since Pyongyang. It breaks his recent formula, and in doing so beautifully demonstrates the aptitude of comics for representing time and subjective experience. It is Delisle’s first nonfiction graphic narrative in which he is not a character: he appears drawn only once in the preface, sitting across from a smoking bespectacled man and pressing play on a tape recorder underneath the words, “The events reported here occurred in 1997, when Christophe André was working for a humanitarian NGO in the Caucasus. The book recounts his story as he told it to me.” André’s first-person voice, matched to Delisle’s drawings, then opens chapter 1 and remains throughout, telling the story of his nearly four months as a hostage after being abducted while on his very first mission as an administrator for Doctors Without Borders. He begins in the past tense but soon switches to the present, narrating day by day the moments and events that structure his experience.

Delisle first read about André, then had a chance encounter with him when Delisle went to meet a friend who worked for the organization at their office. The result was a fifteen-year project that stretches to 432 pages, but rarely feels slow or labored, despite the repetitive promise of the premise. This detailed, intricate drawing of another’s personal testimony is something Sacco has done frequently, but Delisle’s version is quite different. In taking a Doctors Without Borders mission as a frame, Hostage also recalls Emmanuel Guibert, Didier Lefèvre, and Frédéric Lemercier’s The Photographer: Into War-Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders. A new subgenre may be emerging: NGO comics.

André, a French national, had been working in Ingushetia, the Russian republic west of Chechnya, for three months as a financial administrator for Doctors Without Borders when four armed men broke down his bedroom door in the early morning of July 2, 1997, and shoved him into a car in his underwear. As it turns out, they are Chechen rebels, seeking a million dollars from Doctors Without Borders as ransom, and they drive him to Chechnya, although he won’t know this for sure for months; he is shuttled undercover to four different locations, and imprisoned alone. Hostage is the account of his solitary captivity, and it excels in immersing the readers in the lonely and terrifying experience. Most days André is chained in his room, released only briefly to eat and to be escorted to the bathroom. Communication with his captors, with whom he does not share a language, is limited to gestures and unintelligible exclamations; the book peppers readers throughout with untranslated Chechen, staging André’s perplexity. He names one of them Thénardier, after the crooked innkeeper in Les Misérables.

On the rare night that his captors forgot to handcuff him after a meal and bathroom break, André spontaneously fled on foot. Delisle delivers the tense scene in a burst of floating staccato speech balloons over six pages that present André’s terse commands and encouragement to himself as he hits the street: “Don’t run/Button up/Stay unnoticed/People!/Chechens/Keep going.” Eventually, his feet pulped and bloodied from his cheap shoes, he boards a bus, explains he’s had an accident, and is approached by a hospitable young man who speaks English. The man, Aslan, invites him to come home and stay overnight with his family. This family proves to be André’s saviors. They help him—at risk to their own lives—to reconnect with Doctors Without Borders employees in the Chechen capital of Grozny.

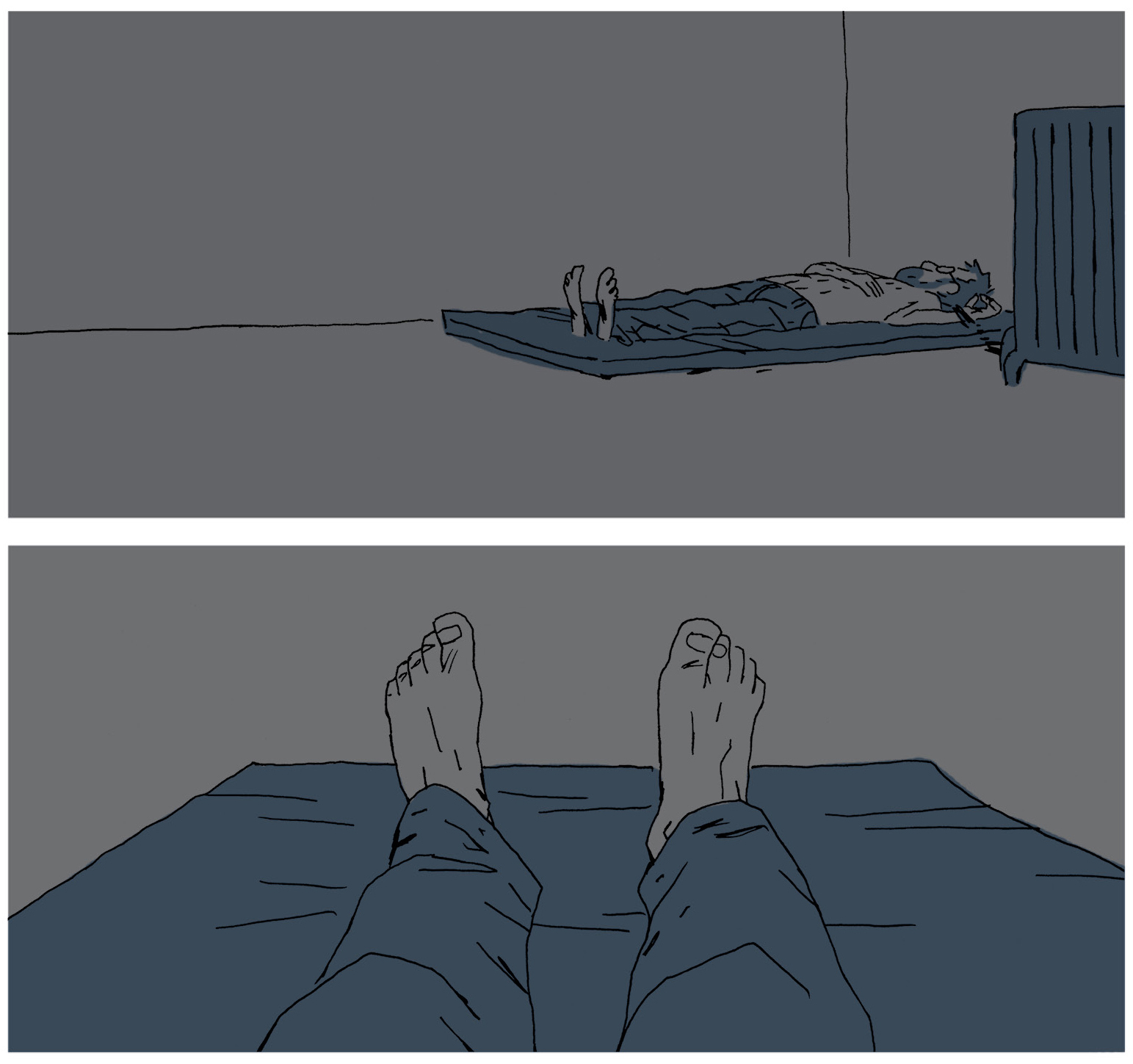

Representing this story, the bulk of which features André alone with his thoughts, is a feat of elegant visual storytelling. Hostage shows us how comics can movingly express an experience like prolonged captivity. Color has an important part: the book unfolds in shifting, murky tones of grey and damp blue. The reader often strains, as André did, to make out his surroundings. Each chapter of the book begins with stark white, with the day of captivity noted in black squarely in the middle—the increment of time André struggled to track in his mind over months (not every day of his 111 as a hostage is recorded, but the book moves forward in time chronologically, offering us, for instance, what happened on day 79, day 80, then day 87).

Regardless of the story it delivers, the most basic narrative procedure in comics is based on the division of time. Usually, this involves enclosed frames that use the space of the page to delineate time: each captures a single moment, and readers infer causality from one frame to the next over the blank space of what is known as the “gutter.” Delisle uses the grammar of comics to great advantage here, slowing down a reader’s sense of time with large, stretched, silent panels that convey the weight and stillness of the moments creeping forward for André. He also brilliantly exploits one of comics’ most interesting possibilities, especially for first-person narratives: the way it can shuttle back and forth on the printed page between different perspectives. In Hostage we move back and forth from seeing what André sees—strange angles from his chained-to-the-radiator or chained-to-the-bed point of view—and sudden dramatic bird’s-eye-view shots of his emaciated body lying on a straw mattress from the height of the ceiling. This alternation keeps the book visually dynamic despite its restricted subject matter, and evokes the disorientation André must have felt.

Advertisement

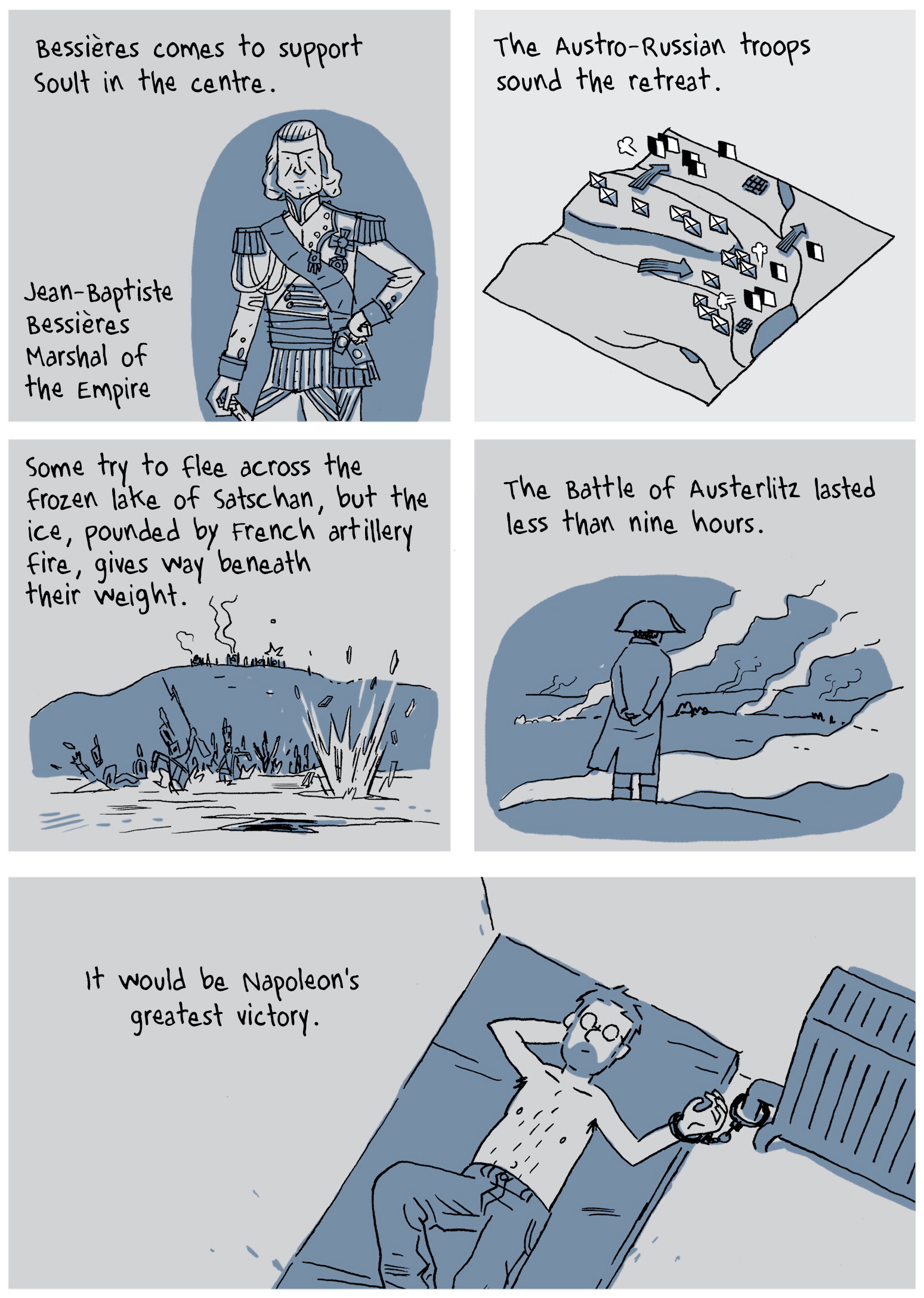

Hostage journeys into André’s reveries—rendered concrete by Delisle—which sustain him while he’s locked up alone. He knows it’s too psychologically dangerous to picture the people he loves—so he decides that as he’s a military history buff, he will recreate, in his mind’s eye, some of his “favorite battles.” André starts with the German campaign, in which Napoleon has just marched on Vienna; the Battle of Gettysburg also makes an appearance. Delisle draws these battles as André sees and narrates them to himself, including miniature maps, for pages at a time, revealing one man’s richly conceived coping mechanism. These battles—their images complete with the charming editorializing of an aficionado—are meditations, appropriate for a hostage, on action and inaction. They offer, like the book itself, a profound window into human resourcefulness.

The book closes on Saturday, October 25, with André en route to Paris. A clipped one-page epilogue explains that the former hostage returned to Doctors Without Borders for another eighteen years, beginning his second mission with the organization only six months after he escaped his disastrous first one. The report on Aslan and his family is brief but tantalizing: after receiving death threats for helping rescue André they became refugees to France, where they were granted asylum. Right now another emerging subgenre, and one to which Sacco has contributed, is comics about refugee experience. The parameters of André’s story seem wide. Yet Delisle keeps the aftermath for all involved and the political background of André’s kidnapping largely if not entirely out of the picture. In making his focus narrow, Delisle departs from his earlier work, and recent comics work so riveted to visually articulating the world-historical stage. Hostage, in its beat-by-beat, day-by-day scope, is ultimately a travelogue about the power of imagination.

Guy Delisle’s Hostage has just been published by Drawn & Quarterly.