When the saxophonist John Coltrane was asked in 1966 what he hoped to be later in life, he replied, “I would like to be a saint.” He would be canonized by the African Orthodox Church in the 1980s, but John wasn’t the only holy person in his family. His widow, Alice Coltrane, who had had spiritual inclinations since childhood, took the Sanskrit name Turiyasangitananda (which she translated as “the Transcendental Lord’s highest song of bliss”) and donned the saffron robes of a Hindu swami in the late 1970s.

An important jazz musician in her own right, Alice Coltrane played piano in her husband’s groups from 1966 until his death the following year. After John passed away, Alice recorded a dozen albums under her own name, ranging from straight-ahead jazz to experimental mixtures of orchestral music and improvisation to Hindu chants performed in gospel arrangements. Her corpus remains one of the most varied and underappreciated in jazz, complicated by her unorthodox religious convictions and the towering legacy of her husband, whose vision she often claimed to be fulfilling.

Alice stopped recording commercial albums in 1978, but she continued creating music with members of the Shanti Anantam Ashram, a religious community in Agoura Hills, California, that she founded in 1983 and would lead until her death in 2007, at the age of sixty-nine. Alice and her congregation produced four albums of their sacred songs, which were released on cassette in limited numbers by Avatar Book Institute, a publishing house associated with the ashram. Selections from these rare and out-of-print recordings were recently released as The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda by the world-music label Luaka Bop, marking the first time these works have been made widely available.

Alice espoused an eclectic set of beliefs drawn largely from Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita and Vedas, but also from Taoism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and ancient Egyptian religion. She claimed to have had mystical experiences since the age of nine and said she was clairvoyant, telepathic, and able to levitate; she told interviewers she could stay awake for days in a meditative trance, and wrote of memories from past lives. Such assertions of supernatural abilities are likely to make many listeners uncomfortable. Yet by all accounts she was beloved by her family, followers, and fellow musicians. It’s worth noting that Coltrane’s ashram was free from the sexual and financial scandals that have surrounded other self-styled spiritual leaders.

Alice Coltrane led services at her ashram every Sunday. Worship was largely centered around a traditional Hindu form called bhajan, or devotional chant, which consists of repetitions of the name of a particular deity and invocations to it. The music the congregation created was a far cry from that of South Asia. Franya Berkman, a musicologist who visited the ashram in the early 2000s, described the weekly services:

[Alice] would make offerings at the altar, take her seat behind the Hammond B3 organ, and begin…. Playing syncopated chords with her left hand and a soaring, pentatonic melody with her right, she would signal the song leader in the men’s section to start the men singing. The women would respond, and blues-inflected devotional music would fill the room…. The congregation would create harmonies and counterpoint, and cry and shout in response to members’ musical and emotional outpourings. They would clap ecstatically, and join in with tambourines and other hand-held percussion instruments.

The result, as the new compilation reveals, was a complex and sometimes befuddling blend of gospel, pop, rock, and Indian religious music. At times the congregation’s music—with its pulsing beats, synthesizers, and indistinct singing—sounds as if it could be field recordings manipulated by a DJ; at other times it seems dangerously close to the New Age fads of the late twentieth century, a hybrid of Eastern and Western spirituality that does little to address the complicated histories of its various influences.

But the recordings on The Ecstatic Music never fall into pastiche or baseless cultural appropriation. The unexpected combination of styles and influences are held together by the passion and devotion of the congregation. As unusual as the ashram recordings might sound to listeners, they contain the music of a religious community that viewed these performances as a sacrament. Coltrane herself was an immensely talented musician who saw music as a way of expressing one’s faith and communicating with the divine, and the songs included on The Ecstatic Music emerged from a lifetime of spiritual and artistic searching.

Born in 1937 in Detroit, Alice McLeod grew up in a family of observant Baptists. Often described as a child prodigy, she began accompanying the choirs at her family’s church at a young age and also studied European piano repertoire. As a teenager, she played at the services of a local Pentecostal congregation. The experience convinced Alice of the religious power of music. “The people in the audience were so overcome with the spirit,” she recalled, “they weren’t singing anymore; some were just walking around the church. Half of the choir had to be carried out.” The belief that music was a means for reaching the divine would stay with her for the rest of her life.

Advertisement

During high school, Alice became involved in the lively Detroit jazz scene, which, in the 1950s, was known for combining bebop with rhythm-and-blues, resulting in a grittier, earthier style than the jazz that came out of the coasts. Prominent musicians Alice played with at this time included the Jones brothers (Elvin, Thad, and Hank), Yusef Lateef, Kenny Burrell, and Bennie Maupin. In 1960, she moved with her first husband, the singer Kenny Hagood, to Paris, where she frequented the apartment of bebop pioneer Bud Powell, whom she considered a mentor.

After her marriage fell apart, Alice lived in New York for a year before returning to Detroit, where she was hired by the vibraphonist Terry Gibbs. In 1963, Gibbs’s band shared a weeklong double-bill at Birdland in New York with John Coltrane’s quartet. Alice had long been fascinated by John’s music, especially his 1961 album Africa/Brass, with its primal-sounding arrangements by the multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy over which John played in a restrained but forceful style, evoking the cadences of a preacher. At Birdland, Alice didn’t dare approach the shy and serious Coltrane. He, however, approached her on the third night, walking behind her backstage while playing a melody on his saxophone. When she told him it was beautiful, he replied, “It’s for you.” By the end of the week, she had left Gibbs’s group in order to travel with John as he toured around the world.

John and Alice shared a conviction that music could be a spiritual practice. Following a revelation in 1957, John’s work took on a focus and urgency that seemed to convey the divine force that he felt underlay all musical expression, as exemplified in titles like A Love Supreme, Om, “Peace on Earth,” “Offering,” “Love,” and “Serenity.” He said that he hoped “to be a force for real good” that could “inspire [listeners] to realize more and more of their capacities for living meaningful lives.” John’s influence on Alice was profound. An intensely studious man, he introduced her to the Bhagavad Gita and other Eastern texts that would later form a central part of her religious beliefs. After John died, Alice never spoke of him as being dead—she referred instead to his “transition”—and in subsequent years she would claim to receive visitations from his spirit.

In late 1965, McCoy Tyner, John’s longtime pianist, left to pursue a solo career, and John asked Alice to join his band. In the mid-1960s, John had begun to explore the irregular phrasing, harsh timbres, and loose beats of free jazz artists such as Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, largely abandoning standard harmonies and forms in favor of more open structures for improvisation. Although Alice had stopped playing piano in order to raise her and John’s children and had no experience with the new avant-garde music, she was swiftly integrated into the ensemble’s atonal, atemporal style. John encouraged Alice to approach the piano as if it were a harp, and she developed a technique that combined shimmering arpeggios with rapidly shifting harmonies, resembling a lusher, less percussive version of Tyner’s playing. Although the Coltranes’ music could be harsh and frenetic or hymn-like and ethereal, throughout it all there was a meditative intensity that drew impassioned responses from listeners. Reactions to their concerts were strikingly similar to those at the Pentecostal services Alice witnessed as a teenager: “Someone in the audience would stand up, their arms upreaching, and they would be like that for an hour or more,” she recalled. “Their clothing would be soaked with perspiration, and when they finally sat down, they practically fell down.”

John died suddenly from liver cancer in 1967, leaving Alice widowed with four children—a daughter from her first marriage and three sons with John. She began to suffer from insomnia, and her weight fell from 128 to 95 pounds. She later called this period her tapas, a yogic term for spiritual austerity, writing that this “purificatory spiritualization [brought] about the expansion and heightening of my consciousness-awareness level.” During this time she began recording her own music and ensembles and developed an interest in Hinduism and ancient Egyptian religion.

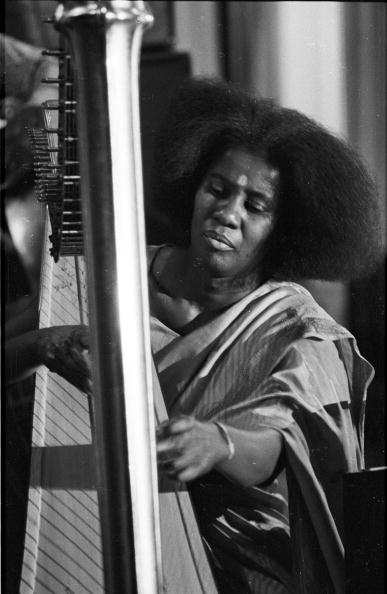

Alice’s solo recordings from the late 1960s and early 1970s—on which she was joined by many who had played with John, as well as other prominent jazz musicians such as bassist Ron Carter and saxophonist Joe Henderson—feature steady rhythms, simple bass lines, instruments from India and the Middle East, and impressionistic, bluesy soloing. Although the music was more groove-based and less dissonant than John’s late work, Alice continued to explore the spiritual concerns that had occupied her husband. She began playing a harp that John had ordered before he died but that only arrived in 1968. Alice’s harp would become a crucial aspect of her music, adding a celestial quality to albums like the majestic Journey in Satchidananda (1971), named after an Indian swami of whom Alice had become a devoted follower. The work from this period is her most celebrated and accessible; in addition to the Eastern influences alluded to in her song and album titles, the music reflects Alice’s education in the church, her experience playing bebop tinged with R&B in Detroit, and her admiration for pop artists like Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles.

Advertisement

Alice’s early albums are remarkably confident and daring for someone who had never before led her own ensembles and who had largely given up public performance in order to look after her family. Her surety is all the more impressive considering that the jazz avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s was almost entirely male. Although some female jazz instrumentalists and composers had achieved renown in more traditional settings, there were virtually no women playing in the avant-garde at the time, and Alice was the first to record under her own name. As Alice herself acknowledged, royalties from John’s music helped her achieve the comfort and financial freedom that other musicians didn’t have; she was also indebted to John for her contract with Impulse! Records, which arose from the label’s desire to gain her permission to issue the vast amount of his unreleased recordings. She would soon become an important artist for the label. Impulse! producer Ed Michel said admiringly that the musicians Alice recorded with “treated her with the respect she deserved and did as they were told. Guys who wouldn’t put up with anything from a lot of people would ‘Yes, ma’am’ her because she earned it.” Using the studio she and John had constructed at their home in Dix Hills, on Long Island, and receiving production credits on most of her albums, she was one of the few major-label jazz artists to have complete autonomy over her work.

Her later recordings for Impulse! were more tumultuous, characterized by rollicking beats, sudden shifts between heavenly consonance and harsh dissonance, and a blistering, bop-inspired technique on electric organ—a striking contrast to her more fluid harp playing. She showed an interest in orchestral music, including arrangements of excerpts from The Firebird on Lord of Lords (1972). (In that album’s liner notes she wrote that she had been visited by the spirit of Igor Stravinsky, who had told her “I wanted you to receive my vote” before offering her an elixir in a glass vial.) She also dubbed string arrangements and organ over recordings of John. The result, released in 1972 as Infinity, was maligned by critics and fans, but the settings Alice created for John’s improvisations are surprisingly cohesive, revealing new aspects of his music and the direction it may have taken had he lived longer.

That same year, Alice moved her family to California, where she opened the Vedantic Center, which soon attracted followers. Four years later, she had a revelation in which, she said, God instructed her to become a swami. Her music changed once again, with the albums Radha-Krsna Nama Sankirtana (1976) and Transcendence (1977) featuring singers performing Hindu chants in bright, joyous renditions that resembled gospel and contemporary pop more than Indian music, avant-garde jazz, or orchestral works. Following her 1978 album Transfiguration, Alice devoted herself entirely to her family and her religious pursuits, and in 1983, she purchased a large parcel of land in Agoura Hills, near Malibu, where she created the ashram.

The songs collected on The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda were recorded between 1982 and 1995. Most of Alice’s arrangements of bhajans, the invocations that serve as the basis for her devotional music, use two-chord vamps and call-and-response between an individual and the chorus or between different groupings of the chorus. Alice primarily plays electric organ and an Oberheim OB8 analog synthesizer, using dissonant chords and occasional blues lines to propel the music forward while creating a dark, ominous texture around the singers; there is little of the sunniness of her earlier renditions of Hindu prayers. One of the most arresting aspects of the ashram recordings is Alice’s use of the synthesizer’s pitch-bending function, with which she makes dramatic sweeps that overpower the singers and resemble air raid sirens. The effect can be startling, suggesting a destructive deity in need of propitiation rather than one offering its divine love. At times the music resembles that of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan in its trance-inducing mysticism; or of Fela Kuti in its simple melodies and propulsive, disco-like beats; or of Stevie Wonder in its imaginative superimposition of gospel music and synthesizers. Yet on the whole this music is unlike anything else.

The simple forms, recognizable harmonies, and repetitive nature of the chants would have been amenable to a congregation of varying musical abilities, but the singers included on this album, many of whom are African-American and were raised in black churches, are outstanding. When singers break off from the chanting with some melisma or other embellishment, the mixing of the recording often makes them sound distant, and the chorus can form an indistinct, ululating mass, requiring close listening in order to discern individual contributions. This is especially true on “Hari Narayan,” throughout which a woman’s sanctified wailing is partially obscured by Alice’s organ and the chorus’s antiphonal chanting. Soloists are recorded with greater clarity. Panduranga John Henderson, a member of the ashram who had been a singer in Ray Charles’s band, delivers a powerful solo in the middle section of “Om Rama,” and the Indian musician Sairam Iyer sings a Tamil poem on a version of “Journey in Satchidananda,” played here at a dirge-like tempo with lyrics celebrating the song’s namesake. Iyer’s voice, lithe and clear, blends impressively with Alice’s organ, following the bends in her tones and nestling comfortably into the timbre of the instrument.

Four of the eight songs feature the voice of Alice herself, who had never sung on her commercial records. Indeed, no one had heard her sing before 1982, when, according to Radha Botofasina-Reyes, a longtime resident of the ashram, “she said she had meditated and the Lord had told her she must sing.” Alice’s voice has a mysterious, androgynous quality, and although it can be out of tune and unsteady, she sings confidently and movingly. As Botofasina-Reyes remembers, “She said [her voice] sounded that way because it was neither male nor female—it was the voice of the soul.”

“Om Shanti” in particular suggests this otherworldly nature. Alice’s rhythmic but airy articulation of the consonant-heavy Sanskrit text—“Ananta natha parabrahman om”—is echoed by ghostly overdubs of her own voice. The key changes from Bb major to G minor, percussion enters, and Alice leads the chorus in call-and-response; her voice gradually subsides as the haunting swells of the congregation become more prominent. Another standout track is “Er Ra,” based on an ancient Egyptian text that, according to the liner notes, has no known translation. Alice sings and accompanies herself on harp, her slow, sparse plucking giving way to waves of arpeggios, and her plaintive voice alternating between raspy vulnerability and fearlessness.

Franya Berkman, whose invaluable study Monument Eternal: The Music of Alice Coltrane remains the only full-length treatment of its subject, argued that Alice’s work could be seen as a spiritual autobiography, in the manner of black female preachers such as Rebecca Cox Jackson and Sojourner Truth, who relied on a variety of styles and modes in order to tell an authentic account of their experiences. So too, Berkman argues, did Alice use whatever means were available in order to express herself authentically. One might wonder why, earlier in her career, Alice recorded virtually unaltered transcriptions of works by Igor Stravinsky. It was, in part, an attempt to claim the worldly Russian as a spiritual composer—after all, he was devoted to the Russian Orthodox Church and composed many sacred works—and to place herself as his spiritual, if not stylistic, descendant. But it was also a fearless assertion of her individuality. She didn’t seem to care that a black woman trained in the church, bebop, and the avant-garde wouldn’t be expected to espouse European modernism; she loved his music, and she made it a part of her own.

It is perhaps this assured, deeply felt eclecticism that has gained Alice a following among younger listeners. A performance one Sunday in May by the remaining members of the ashram as part of the Red Bull Music Festival in New York attracted a notably youthful crowd, and the attendees of saxophonist Ravi Coltrane’s recent two-day run at The Jazz Gallery in Manhattan, at which he played his mother’s music, were more diverse in age than those usually seen at jazz concerts. The presence of other members of the Coltrane family, as well as many musicians, in the audience made the concert seem like a long-overdue celebration of a great but neglected artist who has been recognized as a forebear by a later generation. Although The Ecstatic Music contains devotional music, one needn’t ascribe to Alice’s theology or believe in the veracity of her mystical visions to appreciate the emotional honesty of her work. When asked by an interviewer in 2004 what she demanded of her initiates, Alice replied, “I ask that they be sincere in their purpose.”

The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda was recently released by Luaka Bop.