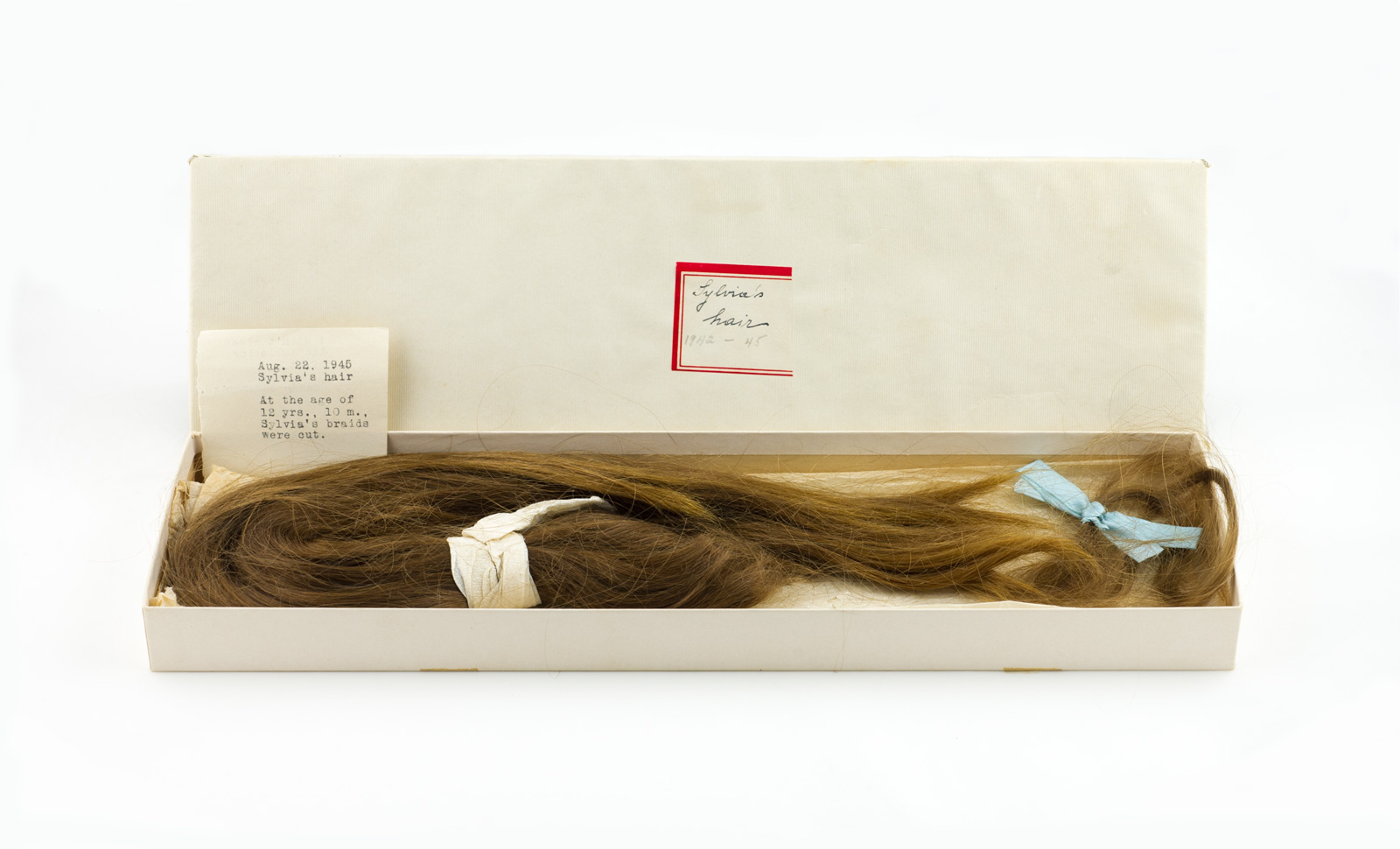

One of the first things you see at “One Life,” the Sylvia Plath exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., is a long chestnut-brown ponytail tied with a blue bow. Plath’s mother cut it off when the poet was almost thirteen, and preserved it along with her letters and photographs. In the context of Plath’s deeply-documented life, this act seems like a ritual of female puberty, a cropping of the poet’s creative powers, and a shearing of their sexual potential. Plath believed that her mother, Aurelia, always disapproved of her poetic career and her marriage to Ted Hughes, and wanted her to choose a more stable profession, as well as a steady and sober husband. Aurelia Plath, widowed and hardworking, understandably channeled all her emotional needs through her children, and especially her precocious daughter, but Sylvia came to feel smothered by her expectations. Perhaps other moms in the Fifties kept a daughter’s ponytail or braid, but they haven’t turned up in museums.

Indeed, among the more conventional artifacts in the exhibition, including Plath’s badge-heavy Girl Scout uniform, her typewriter, and her sketches, the ponytail stands out as a startling portrait of the artist as a young American woman caught between femininity and creativity. Locks of hair, of course, are a traditional memento of distinction and fame. The Ransom Center of the Humanities at the University of Texas in Austin owns a popular collection of the tresses of famous writers, assembled by the nineteenth-century English poet Leigh Hunt. Milton, Wordsworth, Keats, Shelley, and Poe are there, along with Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Charlotte Brontë. But literary locks are usually meager strands. Plath’s thick glossy ponytail is unique, and, indeed, hair is a theme of both her literary legend and the exhibition, which emphasizes her visual imagination and her self-portraits in painting and photography.

Fifty-four years after her suicide at the age of thirty and her posthumous fame as a powerful poet and tragic feminist icon, Plath’s reputation continues to grow. But the organizers of “One Life”—Dorothy Moss, an associate curator of painting and sculpture at the National Portrait Gallery, and Karen V. Kukil, who heads the vast Plath archive at Plath’s alma mater Smith College—aimed to present a sunny rather than suicidal Sylvia. “Here is Sylvia Plath, revealing herself as she wished to be seen, in all her complexity,” Moss said. “I wanted her light side to be balanced with her dark side.”

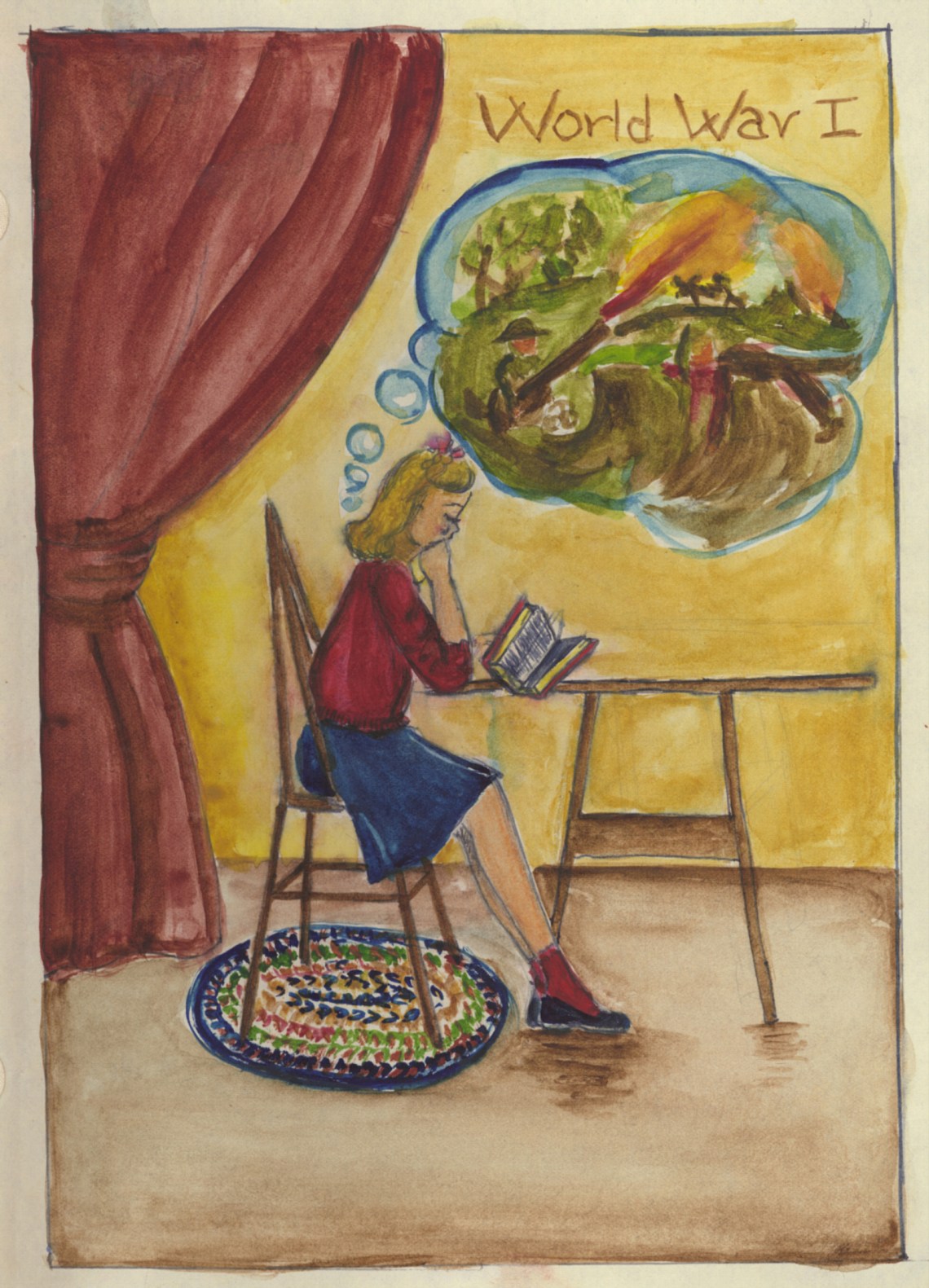

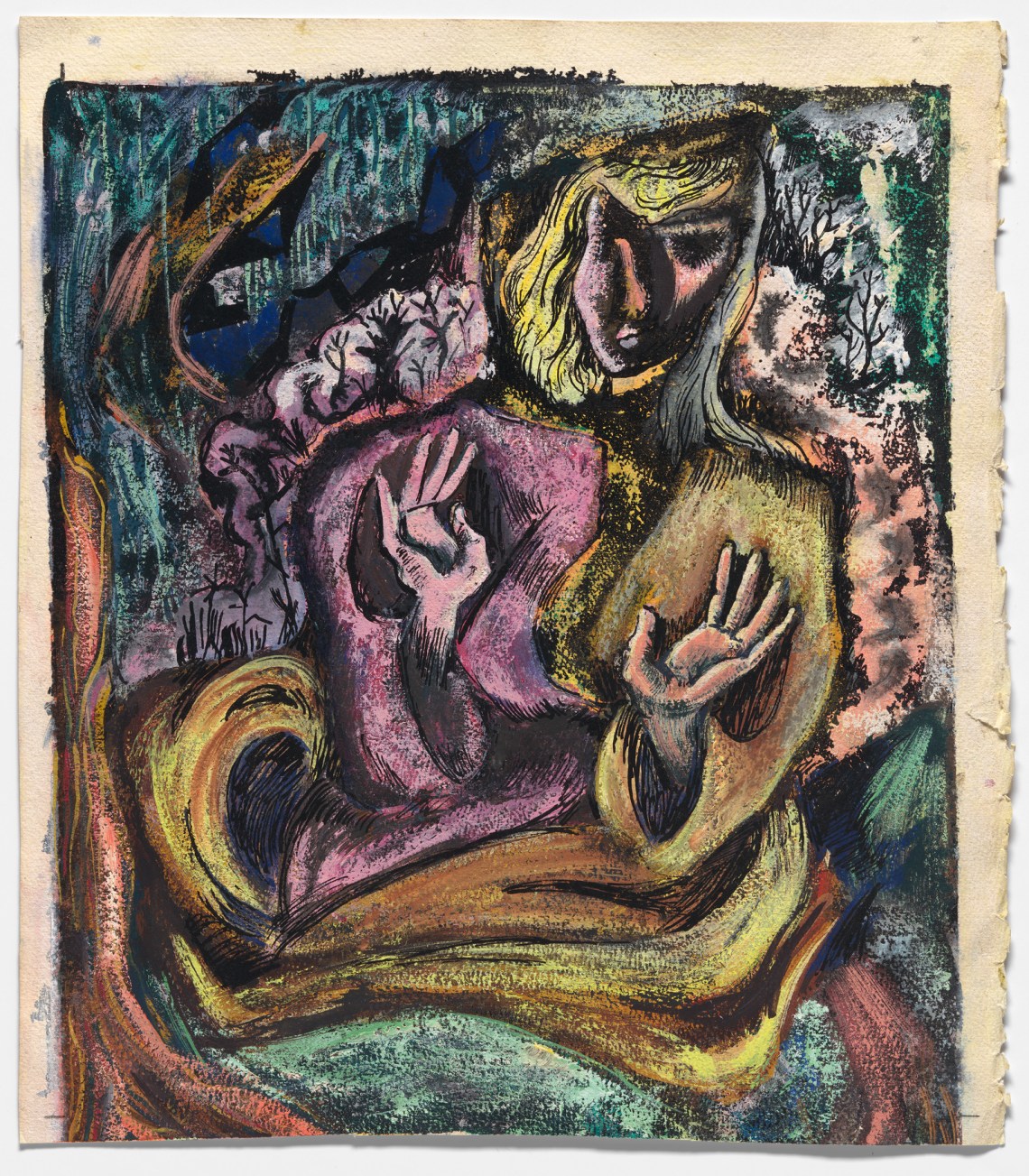

Plath’s light side certainly exists, although any exhibition or book about her attracts those who identify with her dark side. From her Smith senior thesis on the double in Dostoevsky, to the many masks she wore during her short lifetime, Plath was obsessed by divided selves. In her senior year of high school, she painted the cubist Triple-Face Portrait of a woman with green, blue, and yellow hair. She designed and painted clothes for her blonde and brunette paper dolls, perhaps based on Betty and Veronica from the Archie comics but, in any case, archetypal representations of feminine duality from as far back as Scott’s Ivanhoe. Many of her youthful self-portraits show her as a blonde. In June 1954, a few months after her release from the McLean Psychiatric Hospital just outside Boston in 1954, where she underwent electroshock treatment, Plath bleached her hair. Was it also a kind of auto-therapy? Discussing depression in a symposium on the fiftieth anniversary of Plath’s death, Lena Dunham, the creator and star of the HBO series Girls, wondered whether Plath might have been saved if she had access to good modern medication—if she’d lived today, at “a time when psycho-pharmacologists are no more shameful to visit than hairdressers.”

The exhibition includes a print of one of the much-reproduced photographs of Plath with a platinum-blonde pageboy, taken by her boyfriend Gordon Lameyer in July 1954, on the beach at Chatham, Massachusetts. The brochure calls this her “Marilyn Monroe” pose; Monroe’s stardom in Gentleman Prefer Blondes (1953) had established her as the new Jean Harlow, the blonde sex symbol. Until 1956, however, when Clairol launched its first ad campaign, respectable women and college girls, unlike movie stars, did not bleach their hair. It would be years before women could embrace the slogan “If I have only one life, let me live it as a blonde.” For Plath’s generation, a visit to the hairdresser could also be shameful for an aspiring woman poet and intellectual.

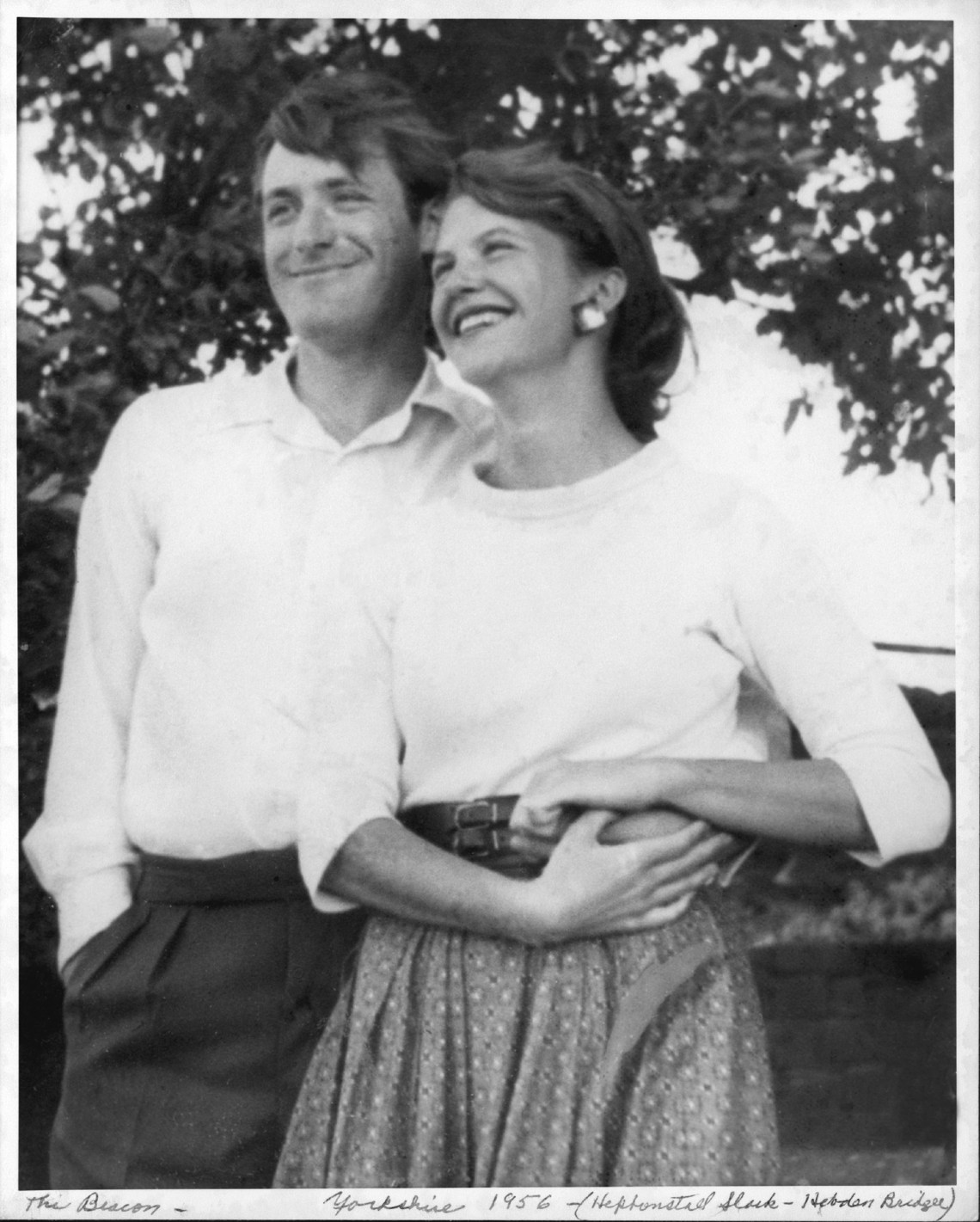

In late August, preparing to return to Northampton, she dyed her hair back to brown. As she wrote to her mother, “my brownhaired personality is most studious, charming and earnest… this year, with my applying for scholarships, I would much rather look demure and discreet.” In a letter to Lameyer on September 24, she announced the change: “Gone is the frivolous giddy gilded creature…. Here is a serious, industrious, unextracurricular unswerving creature who, if you looked closer, might admit to being me!” Other photographs in the exhibition show her as a young bride with brown hair, and later as a young mother with her children, her long reddish-brown hair pulled up and crowned by a heavy braid.

After her suicide in February 1963, people who had known Plath recorded their memories, and many remembered her, mistakenly, as a blonde. The novelist A.S. Byatt told an interviewer for The New York Times Magazine in 1991 that she remembered Plath at Cambridge as a “as a made-up creature with no central reality to her at all,” a girl with “bobby socks and totally artificial bright red lips and totally artificial bright blonde hair.” Ironically, these memories are made-up, too. Plath was not a blonde at Cambridge, nor did she wear bobby socks. Yet the director Jonathan Miller, another Cambridge undergraduate in 1955–1956, also recalled Plath as a “rather big, blonde girl” who awkwardly played a bit part in a student production of Bartholomew Fair. For them, the blonde girl was a clumsy interloper among the Cambridge art crowd, who flaunted her sexuality; she was certainly no substantial student or actress.

Byatt and Miller may have been been projecting their own prejudices about pushy Americans onto Plath. But Anne Sexton knew Plath well; in 1959, they both took a poetry workshop in Boston with Robert Lowell. Eleven years later, Sexton, too, remembered her as “intense, skilled, perceptive, strange, blonde, lovely Sylvia.”

Plath’s hair and appearance came up again this year with the publication of the first volume of her unabridged letters, from 1940 to 1956, also edited by Karen V. Kukil along with Peter Steinberg. Feminist readers commented indignantly on the difference between the covers of the monochromatic American edition from HarperCollins, which shows a demure snapshot of Plath in a belted black coat and a dark pageboy; and the British edition from Faber & Faber, which uses another full-color photograph by Gordon Lameyer of Plath posing on the beach in a bathing suit and smiling directly into the camera with bright red lipstick and shiny blonde hair. Writing in The Guardian, Cathleen Allyn Conway called it Plath’s “cheesecake bikini shot” and protested that Faber has used the image “to make her appear trifling or superficial,” and, perhaps, to sell more books. Actually, it’s not a bikini, but a two-piece white bathing suit Plath had been wearing since 1952, and it’s hard to believe this cover will entice casual shoppers to buy a weighty 1,388-page volume priced at £35. In an echo of Plath’s words, however, Conway charges that “presenting female writers as sexualised and frivolous diminishes their intellectual credentials, tarnishes their work as slight, not to be taken seriously.” She concludes that “we know brunette Sylvia was how Plath wanted to present herself.”

Brunette Sylvia was certainly the way Plath felt a serious woman writer should present herself. In any case, a representation of Plath is still a blank slate on which readers, curators, observers, and fans project their views of her and their assumptions about the proper portrait of the young female artist. Plath anticipated that she would become famous for her sexuality and her suffering, as well as for her poetry. In “Lady Lazarus,” she speaks in the voice of a terrifying alter ego, a suicide survivor and femme fatale who rises from the ashes with her red hair and eats men like air. Lady Lazarus angrily warns the voyeuristic spectators that they must pay to see her:

For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge

For the hearing of my heart—

It really goes.And there is a charge, a very large charge

For a word or a touch

Or a bit of bloodOr a piece of my hair or my clothes.

The words, the clothes, and the hair are on view at the National Portrait Gallery. But admission is free.

Advertisement

“One Life: Sylvia Plath” is at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery through May 20, 2018.