“We do not speak of designing a picture or a concerto, but of designing a house, a city, a bowl, a fabric. But surely these can all be, like a painting or music, works of art.” The words are those of Anni Albers, who spent a long and intimidatingly productive life attempting to prove exactly this assertion—that houses and cities, bowls and fabric, can be as much works of art as pictures or concertos, sculptures or frescoes. A half-century on, few people would claim that architecture doesn’t qualify, and thanks to Grayson Perry and Edmund de Waal, contemporary ceramics carry the gloss of art-world respectability.

But what about weaving, Albers’s chosen discipline? We may think of video, graffiti, sound, and live performance all as art—even conceptual parades starring the general public—but textiles we instinctively tend to place on the other side of that Manichean divide: they’re design. Worse, they’re “craft.”

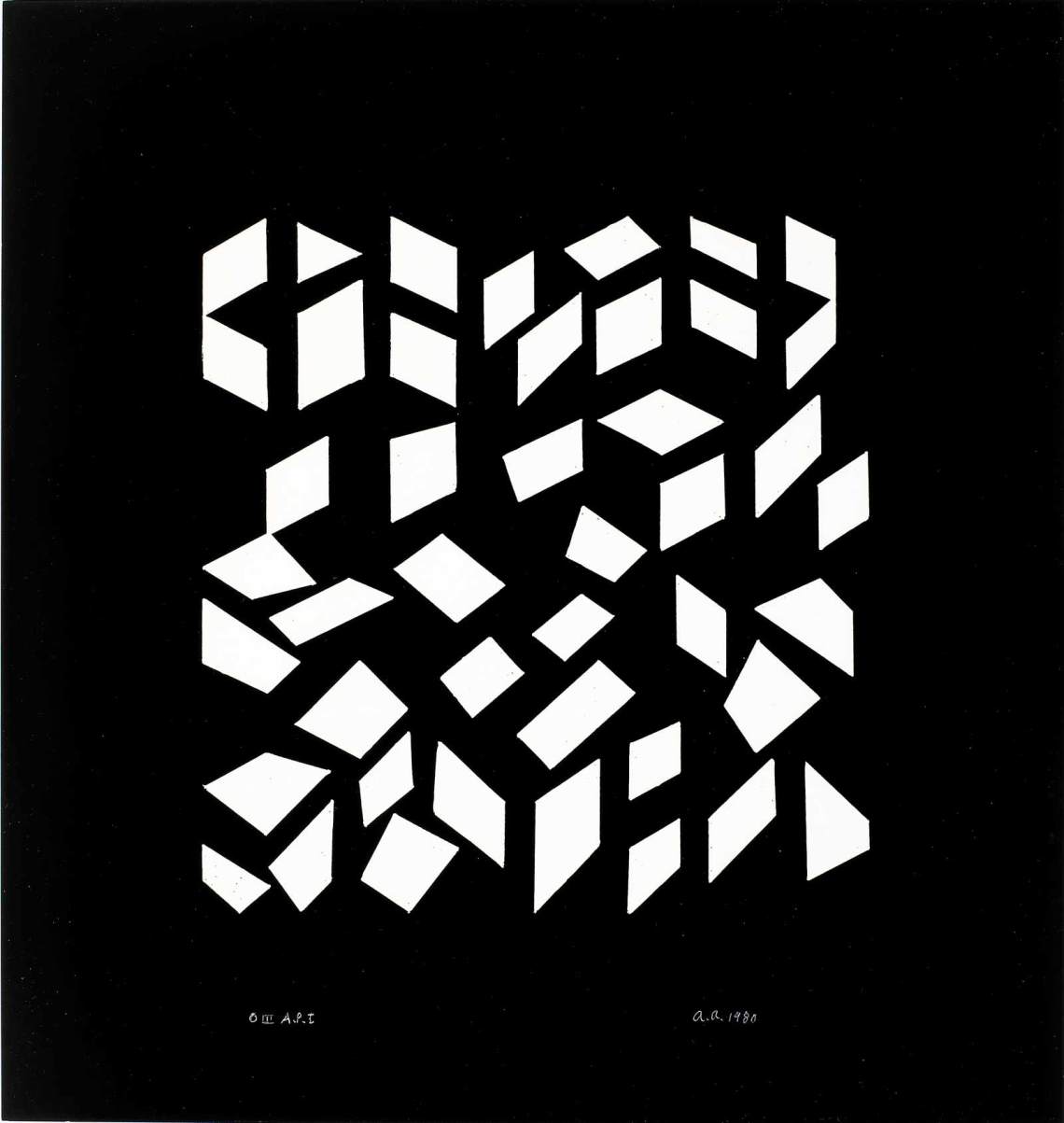

These are, in any case, thoughts that occur as the glass elevator glides up through Frank Gehry’s billowing Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, toward a major solo exhibition devoted to Albers’s work, “Touching Vision.” The show is an act of reclamation, even rediscovery. Much like the genre in which she operated, Albers has been shunted to the margins; it has been over a decade since she was exhibited at any scale in Europe, and nearly twenty years in the United States. Yet she appears to be edging her way back into vogue. In addition to the Guggenheim exhibition, a keystone of the Bilbao museum’s twentieth anniversary this autumn, there was a combined show with her husband, Josef Albers, last spring at Yale, and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf and the Tate Modern in London will collaborate on a joint retrospective next year. Not to be outdone, MoMA has recently included her in a group exhibition about female artists and postwar abstraction, and her gallery, David Zwirner, has published a handsome facsimile edition of a late-period Notebook, eighty-odd pages of neatly penciled triangles and grids on green-tinted graph paper. Enigmatic and spare, these sketches underline the philosophy behind another Albers pronouncement: “Learning to form makes us understand all forming.”

What strikes you as you enter the Guggenheim show is: Why on earth should she have been forgotten at all? One of the first pieces is also one of Albers’s earliest, a design for a wall hanging executed in 1926, while she was still a student at the Bauhaus in Weimar. She had arrived feeling “a tangle of hopelessness” and taken a textile class, grudgingly, because it was the only one on offer to her as a female student. Despite the poor tuition, she quickly realized that she had found her métier. The design is only thirteen-and-a-half inches high, in pencil and gouache: a rectilinear, Mondrian-like puzzle of yellow, black, and blue stripes and blocks, enforced by the weaving style Albers selected. Yet the work has the precision and grace of a Bach fugue: themes sounded and reconfigured, echoes, repetitions, and variations, all assembled with élan and poise. Woven into a silk, rayon, and linen hanging by her Bauhaus colleague Gunta Stölzl, forty-one years later, it still looks immaculately contemporary. From the “tangle,” she had found shape and line.

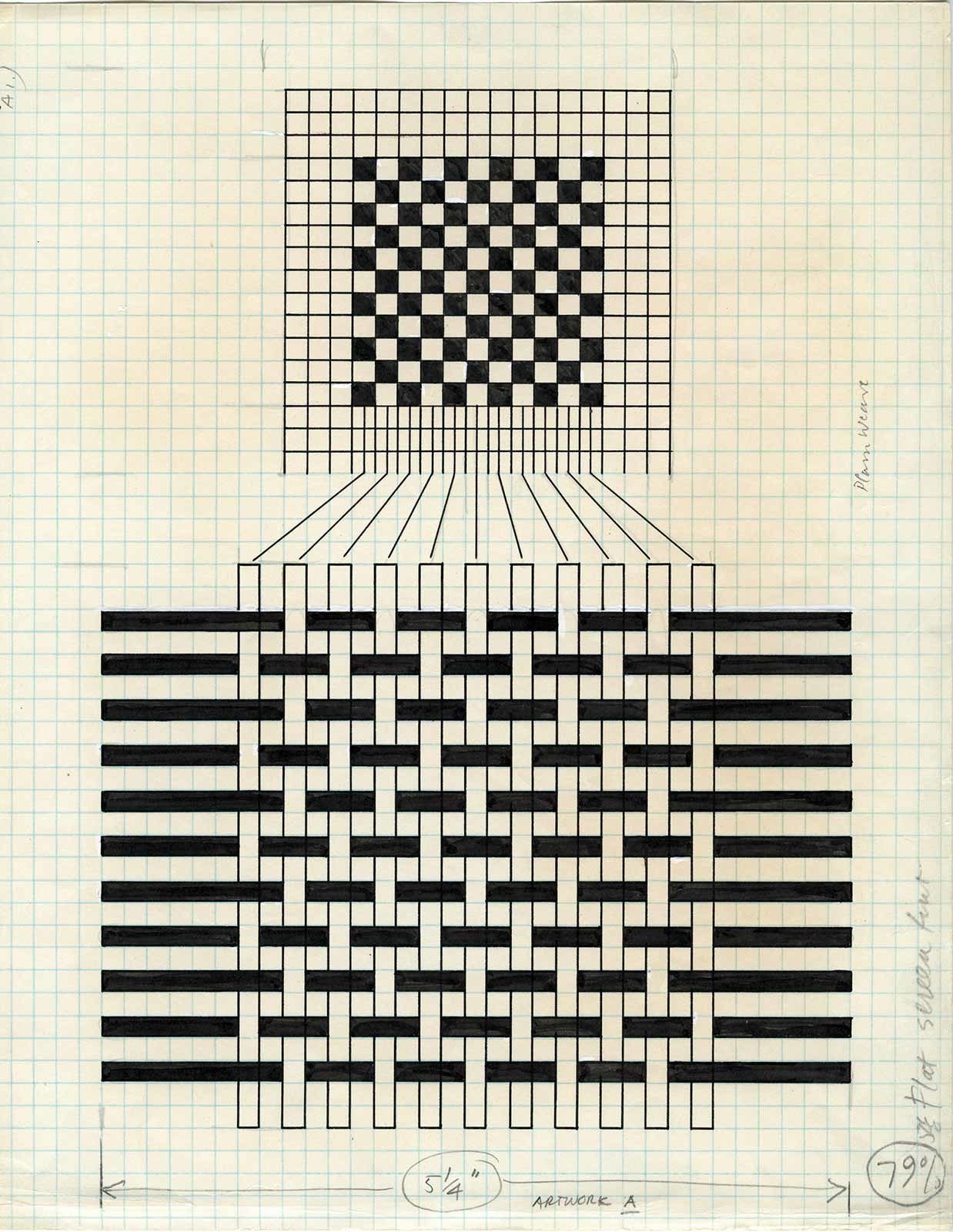

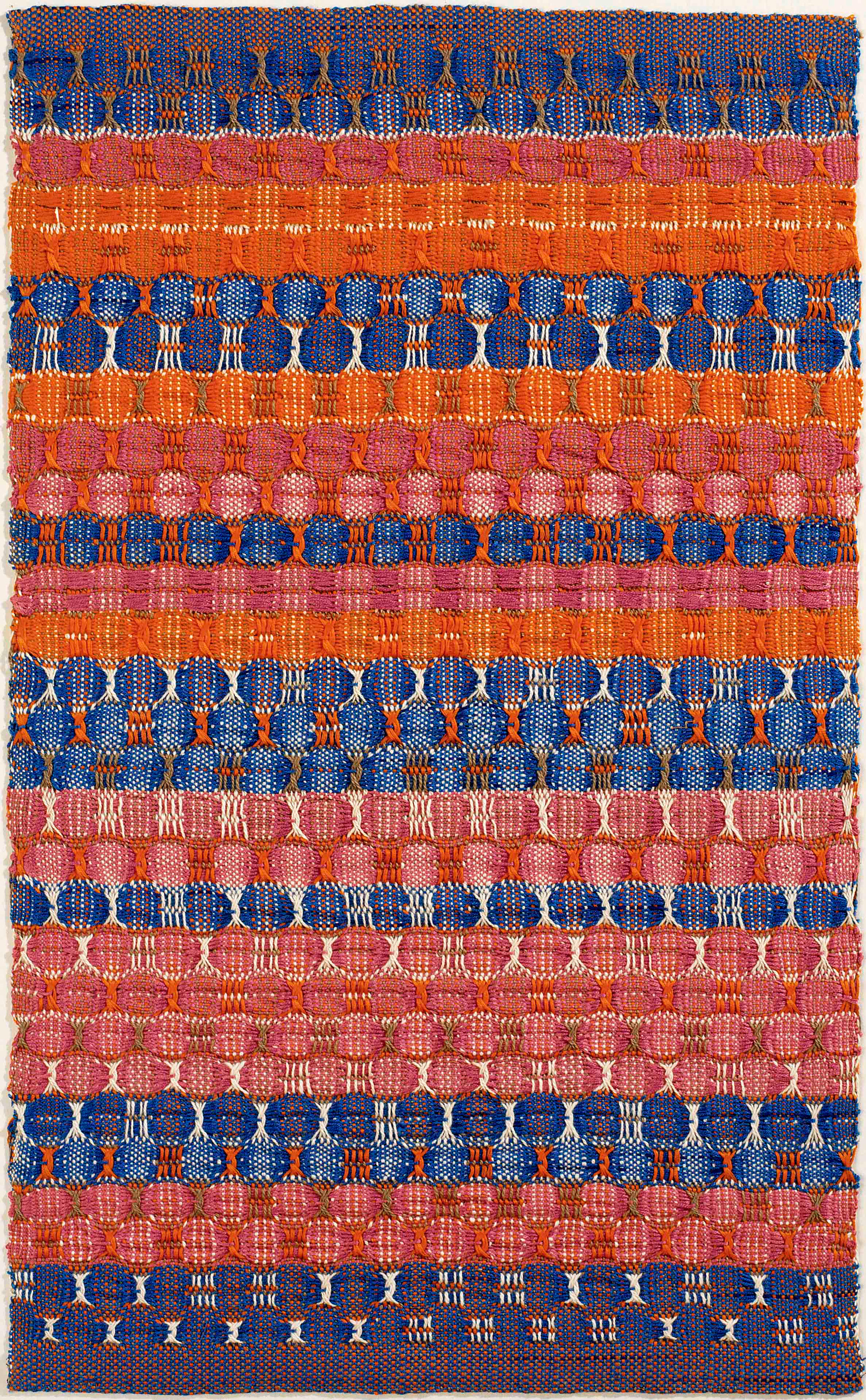

Albers saw no distinction between textiles that had “use” and those that were decorative, and some of the humblest objects in the show are infused with ingenious beauty. A child’s rug designed in 1928 is a serene study in crimson, azure, and eau-de-nil squares that brings to mind paintings by one of her teachers at the Bauhaus, Paul Klee. (One would need to love one’s offspring very much to let them stomp all over such a beautiful piece.) Albers’s graduation piece, a wall covering made a year later, cleverly unites traditional cotton chenille and the new high-tech fabric of cellophane to absorb as much sound and reflect as much light as possible. Her brain was always busy. A series of studies on paper from the early 1940s playfully builds complex figurations out of a few keystrokes on a typewriter—brackets, colons, slashes, capitals, lower-case “s’s.” An indefatigable writer and lecturer, Albers enjoyed working with words as well as fabric, as her monumental 1965 treatise On Weaving (recently republished in an expanded format) attests.

Advertisement

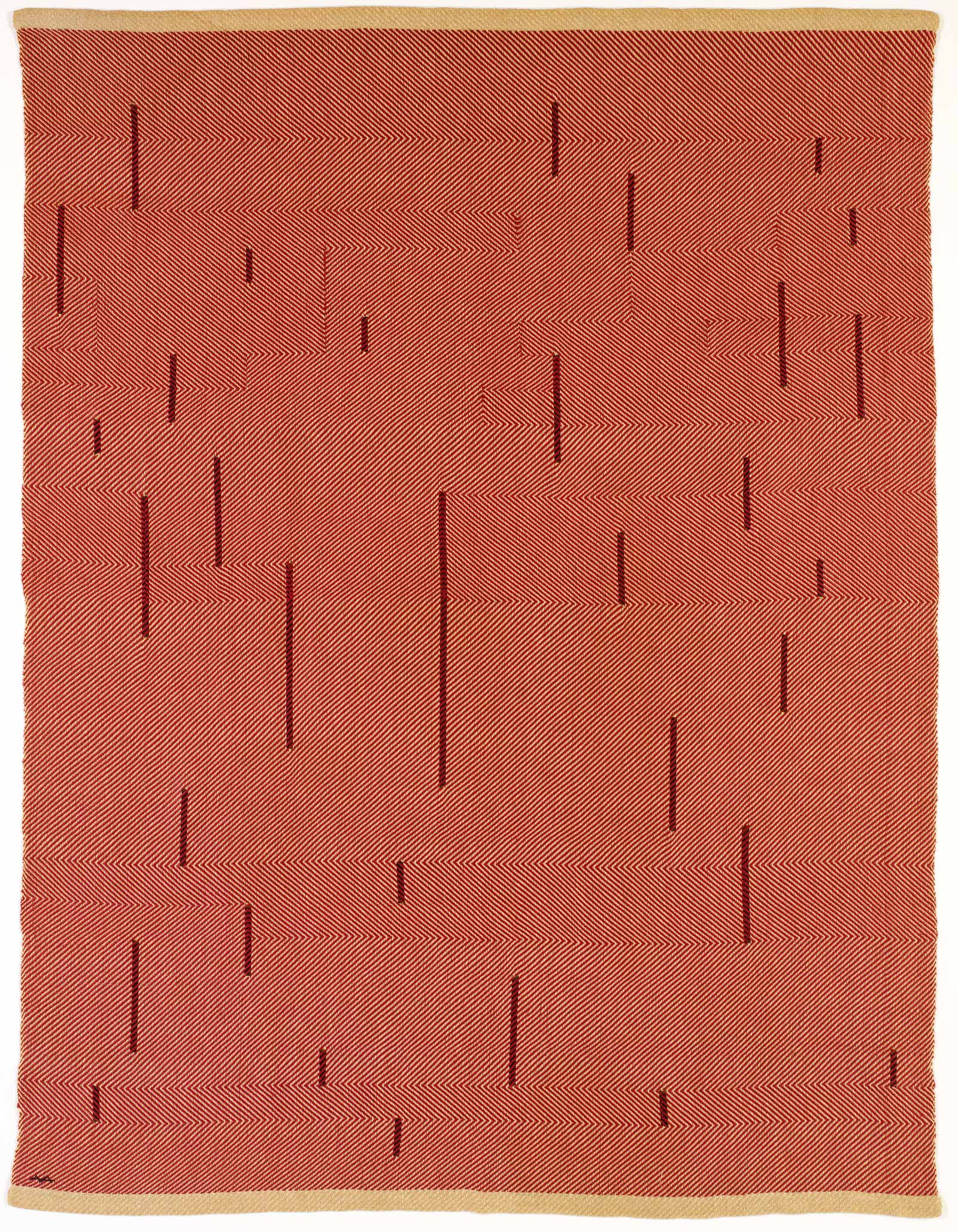

Albers’s eye for balance and harmony was impeccable. A cotton and linen wall hanging, With Verticals (1946), is at first glance little more than a pinkish ground incised with black stripes of varying lengths. But peer closer and observe the intricate diagonal twill that demarcates the space, and the minimalist rigor with which those verticals—thirty-three in all, of seven different lengths—are arranged. Again, the forms seem almost musical; this could be a graphic score by John Cage, an artist Albers greatly admired. Another “pictorial weaving” from the same period, City (1949), seems more casual: rough swatches of yellowish and black cotton, protruding from a coarse linen background. Only when you gaze at it for several minutes do you glimpse the hazy outlines of roofs and windows, perhaps an expressway or river, suggested by the title. In the words of Nicholas Fox Weber, a friend and critic of Albers’s and the executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, “You see neighborhoods; you hear populations; you sense traffic rushing along.”

The important word there is “sense.” In On Weaving, Albers was insistent that what she called “Tactile Sensibility” was crucial to our understanding of art, and of textiles in particular. While our visual sense had grown increasingly sophisticated, she argued, we were losing contact with our sense of touch: “Unless we are specialized producers, our contact with materials is rarely more than a contact with the finished product. We remove a cellophane wrapping, and there it is—the bacon, or the razor blade, or the pair of nylons.” Alas, the Guggenheim curators don’t permit you to stroke the lustrous creations on the walls, but they have placed a perspex box near the entrance containing samples of jute, linen, and wool, as well as polymers such as rayon and cellophane. To rummage in that box is to feel what Albers felt. It was a kind of aesthetic synesthesia: “We learn to listen to voices,” she wrote in the mid-1940s, “to the yes or no of our material, our tools, our time.”

By the time Albers was forming these thoughts, she and Josef had been forced to flee Germany by the Nazis. They relocated to the United States in 1933, at first teaching at the newly established Black Mountain College in North Carolina, then moving to Connecticut when Josef joined the faculty at Yale in 1949. By that time, they had begun to make regular trips to Mexico in search of traditional textiles and objects, and later to Cuba, Chile, and Peru. Some of their spoils feature in the Guggenheim show. Anni, in particular, was deeply affected by her travels to the historical fountainheads of weaving, and by her contact with South-American artists using ancient techniques; her own weavings acquired the energy of discovery. One of her best-known creations, Red Meander (1954), later reworked as a series of screenprints, resembles the ground plan for an ancient labyrinth, with hints of the blocky Peruvian patterns she knew intimately. Somehow, it also calls to mind the childlike exuberance of Keith Haring.

Why has Albers been so neglected? The startling thing is that it wasn’t always so. In 1949, the same year she moved to Yale, MoMA hosted a solo retrospective, its first devoted to a textile artist. It traveled to an astonishing twenty-six galleries and museums around the United States and Canada. Within her lifetime, Anni was significantly better known than Josef, at least in North America.

The liminal status of her artform is somewhat responsible for her partial disappearance. Of course, this is a case of gender as well as genre—or a malign combination of the two, whereby a female artist who works in a “domestic” artform with links to indigenous communities is easily sidelined. Albers may be the star of the Guggenheim’s anniversary season, but she cuts a lonely figure in Bilbao; during my visit, I wandered through room after room of Richard Serra, Bill Viola, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly, and counted a total of two other female artists, Jenny Holzer and Louise Bourgeois (the latter represented by one of her enormous Maman spiders, on permanent display): an abjectly familiar demonstration of how the art world still functions. At Black Mountain, Albers made a point of doing what the Bauhaus had failed to do, and treated male and female artists as “coequals more than… opposites.” It has taken the rest of us far too long to catch up.

Advertisement

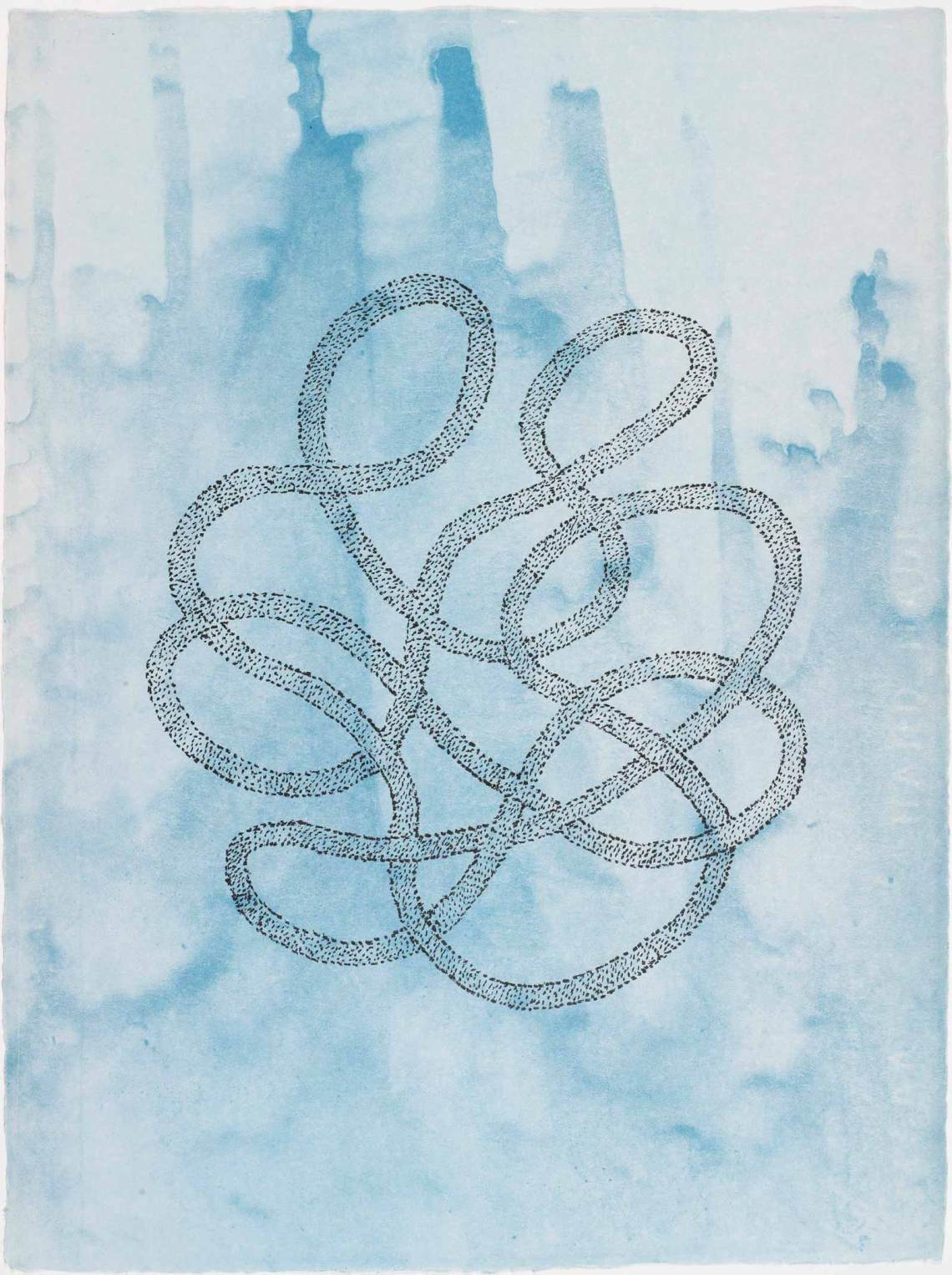

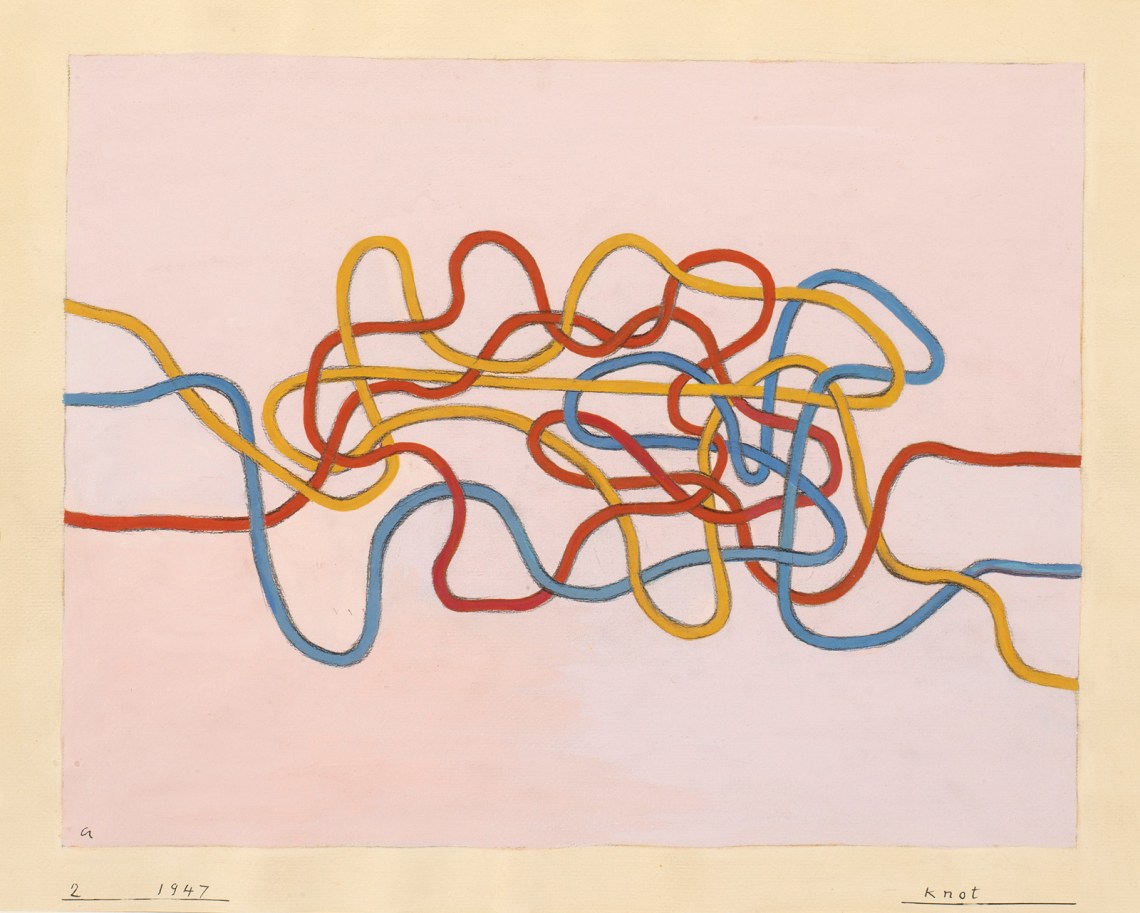

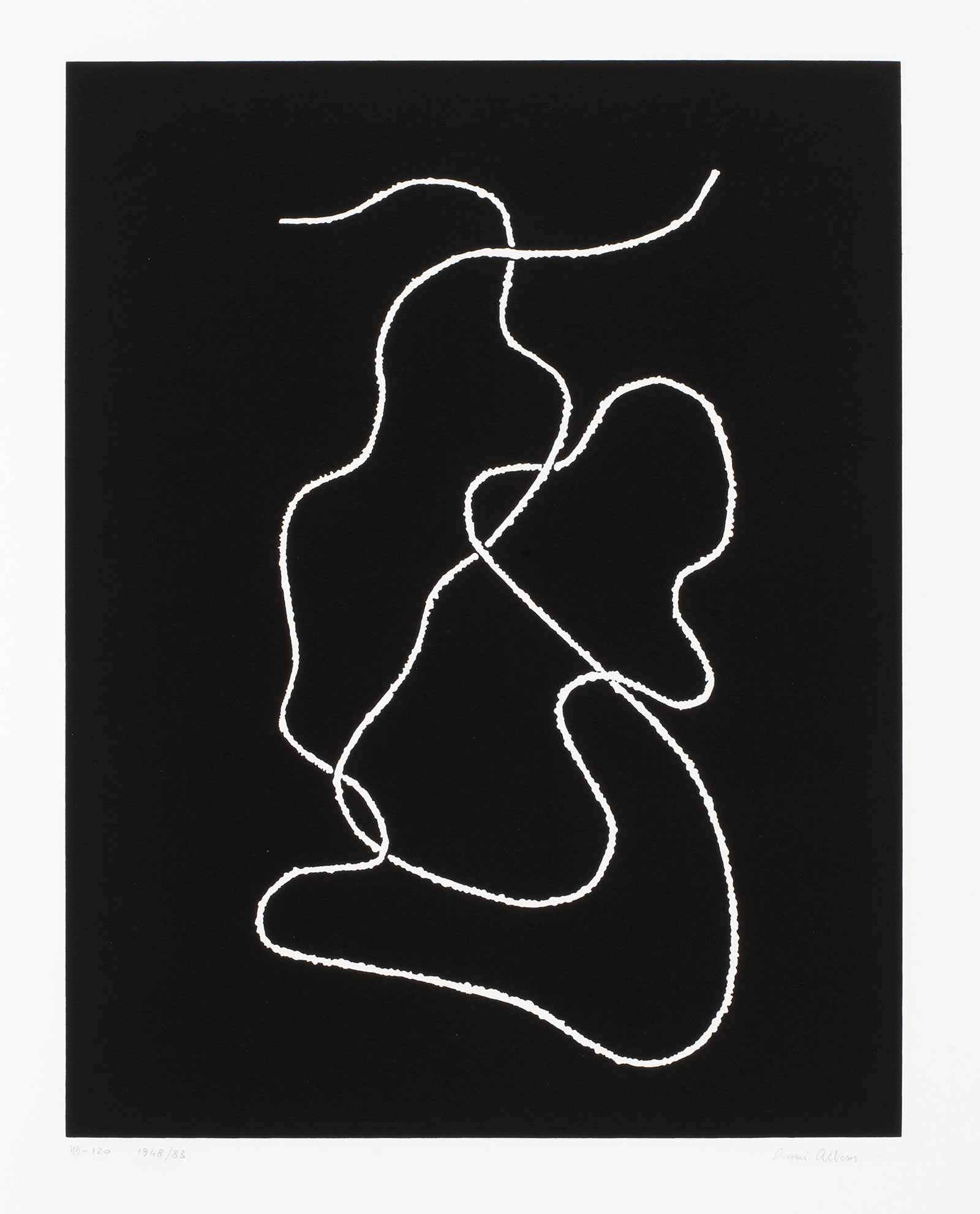

All the same, one of the most powerful aspects of the Guggenheim show is its sensitivity to the friable, fragile nature of Albers’s works: that while the art she made may persist, its material substance will inevitably fade and fray. This transience was her intuition, too; she wrote movingly of “the nomadic character of things made of threads.” One of the last works in the show is Connections (1983), a screenprint on which a single rough white thread snakes through a void of somber black. A nod to the deceptive simplicity of Albers’s practice, it is also, surely, a quiet tribute to her teacher Paul Klee’s suggestion that drawing is “taking a line for a walk.” In On Weaving, Albers settled on a more sonorous phrase, just as resonant: “the event of a thread.”

“Anni Albers: Touching Vision” is at the Guggenheim Bilbao through January 14, 2018. Anni Albers: Notebook 1970–1980 is published by David Zwirner Books.