In my mind, the scene of the accident was always the same. It didn’t clearly make sense how it happened, but that didn’t matter. When it played out behind my closed eyelids, I saw my truck, a late-Eighties Toyota 4Runner, stopped perpendicularly to the main street in the northern side of downtown where we lived in Missoula, Montana. Sometimes, I saw myself slumped over in the driver’s seat with the whole side-panel caved in. Other times, I was flat out on the pavement in the turning lane, our red-and-blue plaid wool blanket over my upper half. Mia, my oldest daughter, who was seven at the time, was never there. But Coraline, less than six months old, always was.

Through several variations, Cora screamed from her car seat in the back of the truck, still facing backwards, her footed pajamas barely reaching the end of her seat. Or she was still strapped in, but in the middle of the street, the truck between us, watching emergency workers walk past her, first with interest, then with confused frustration. The scene would play on like that, with my body carried away on a stretcher, my truck towed, someone cleaning up the glass and fluids left behind. Coraline grew increasingly uncomfortable, and nobody was there to pick her up. Nobody came to get her. I was all she had, and I was gone.

This scene came into my head often. I couldn’t seem to stop it. Coraline would be cradled on the nursing pillow in my lap, asleep, done with nursing but not willing to unlatch from my breast. I’d stare at her, seeing the possibility of her left alone in the street with no one to comfort her, and start to cry. This little human being, whom I had chosen to have and raise alone in a moment of stubborn empowerment, needed me to provide her with warmth, food, shelter, and love, without any thought for my own mortality.

This recurring vision came barely a year after I had, at age thirty-five, completed my senior year of college, graduating with a bachelor’s in English and Creative Writing and finally achieving a dream that had begun nearly ten years earlier. Only a year and a few months had passed since I’d made the decision not to abort the pregnancy that would lead to Cora’s birth, despite needing food stamps to feed myself and my first child, Mia. We still relied on government assistance for food, housing, health insurance, and our electric bill.

I’ve joked with friends that in choosing to keep a pregnancy that began with a one-night stand, knowing I’d be on my own, I’d severely overestimated my abilities. The truth is, after years of emotional abuse and manipulation from Mia’s dad, I wanted the chance to have a child on my own terms.

We had been without a home before, after I told Mia’s father that I was pregnant and that I was keeping the baby. I’d found a perfect little cottage, where Mia was eventually born, but the owner died a week after. Mia’s dad had been so excited about fatherhood in those weeks that it seemed safe to move in with him again. So safe that I combined our bank accounts. He spent my savings in a month. When I asked if I could start working on the weekends, he told me he didn’t want to waste his free time having to watch the baby. When the holidays came around, I cried in secret at night, miserable.

For months after Mia was born, I spent my days alone while her dad worked. He hated that I was at home, that I lived with him, that I’d decided to have his baby. He hated me every second of the day, so much so that I was sure his daughter felt it, too, when he yelled at me over her wails. She was barely old enough to crawl when he kicked us out.

I didn’t want to be a single mom. My family couldn’t help, but it didn’t stop me from asking. I stayed with my dad and his wife for a few weeks before he started asking when I was going to move out. Working my way down a long list of homeless shelters, I found what seemed like the only vacant spot north of Seattle in, coincidentally, the town we’d just run from. Moving there brought relief, gratitude, and stabbing pains of failure. I’d failed to provide a family, a home, a good mother, for my daughter. I’d failed to make it outside this tiny town. I couldn’t feel anything else but that.

Advertisement

I scrubbed the floor of the homeless shelter we lived in—a little cabin we thankfully had to ourselves—so Mia could scoot around on the tile without getting dirty. For Mia’s first year, despite the difficulties, I was never completely without support. I’d been able to save a little money before she was born. I didn’t have to work or worry any more about paying rent for the trailer we’d lived in with her dad. Even though we’d become homeless, there were housing programs in place that would carry us to transitional housing, then our own apartment, with a voucher that paid the rent. My caseworker at the Housing Authority in the small, ocean-side town of Port Townsend, Washington, gave me comfort, stability, and a sense of hope. She felt like a relative when she called to check in on us.

We were allowed ninety days at the shelter. So I had to find not just a job, but stable employment, and fast. My résumé had awkward gaps, especially after 2008, when the recession took hold. Nobody wanted to hire someone who needed to work during daycare hours—not even the coffee shops I applied to, thinking I’d get at least an afternoon shift with my ten years’ experience. When I said the hours I could work were limited, their eyes lowered. That was the end of the interview. Going back to school, to get some kind of degree beyond high school, turned into my only option. I could take classes online at first, doing homework late into the night after Mia went to bed. Slowly, I chipped away at the list of required core credits while working a day job as a maid.

When I’d found out I was pregnant with Mia, I’d thrown the application for the writing program of my dreams at the University of Montana into the garbage. Five years later, I filled out the application again. Once my admission was granted, I never doubted my decision to move us to Missoula, so far from anything we’d ever known. Mia’s dad consented, somewhat easily, and signed the court documents to allow our relocation. Maybe he knew my determination would will me to fight. Or maybe the offer of lowering his child support payment by $200 was too good to pass up. He still blamed me for moving his daughter away from him. It fueled his anger and, far more than the physical distance, made him separate himself more from her emotionally.

By the spring of 2012, I was walking the same halls of generations of writers and poets before me—James Welch, Richard Hugo, William Kittredge. And I met Judy Blunt, whose book, Breaking Clean, had a story similar to my own. She was the head of the Creative Writing department that year. I sat in her office, knowing that she, too, had started college at the same school later in life, with not one kid, but three.

“I want to be a writer,” I said out loud, maybe for the first time. I wanted to tell her that it was all I’d ever wanted to be since I was in the fourth grade, when my English teacher Mr. Birdsall made us keep a journal, and that I’d kept one ever since. I knew of no other dream than to write. I wanted to tell her that I’d put off settling into being a real writer to live a life worth writing about. Now I needed to learn how to process my experience, to put it on the page in a way that wasn’t just late-night scribbling. But Judy didn’t respond to my proclamation. I figured she probably heard that a lot. I lowered my eyes. “But I’m a single mom. It seems so frivolous to get an arts degree.”

Though I’d weighed the pros and cons of obtaining a degree in English, and listed the ways it could be considered useful, even practical, to have a four-year degree in language arts, it still seemed like a huge risk. I wanted college to help me support my family, be a contributing member of society, get off food stamps. But what I wanted most of all was a book I’d written to hold in my hand.

School drove me deep into debt. I’d never be able to afford writing retreats, or for my writing to be an art that would get me published but without pay. Time to write, in that sense, was a privilege not granted to me. Writing had to support us. I instinctively felt that publishing a memoir was a major destination along the road to a stable writing career, but it was one I had no directions for. It stretched out before me, glimmering in the distance, and often felt like an impossibility founded on pure faith in my ability, or pure stubbornness.

Advertisement

Judy offered neither advice nor judgment. She told me about passing her kids from one person to the next so she could focus on her writing workshops. She told me about writing her book in the hours before dawn, before she went to work sanding and refinishing wood floors. When she spoke of her writing process, it didn’t resemble the image I had of a large desk looking out through bay windows over pastoral scenes—an artist waiting for inspiration, unconcerned about how bills would be paid. She talked about writing the same way she did about sanding a floor. It was gritty, dirty, and hard. Work that, with my blue-collar roots, I could understand.

I suppose I followed her example. Mia bounced from one babysitter to another, often coming with me to class. My professors didn’t seem to mind the kid with headphones, slurping chocolate milk, stinking up the room with a Happy Meal. Once, as we were leaving, my writing instructor, the great Debra Earling, bent down to shake hands with Mia, only five at the time. “You know your mom’s a very good writer,” she said. Mia stared, and though she doesn’t remember the moment, she started saying she wanted to be a writer after that.

Every time my car broke down during those years, or I had to fill out renewal forms for our food stamps, my stomach clenched in selfishness and guilt. We were struggling like this because I had chosen to get an art degree instead of work. Being on government assistance, that didn’t seem like an option for me, let alone one to accept, even though it never felt like there was any other option but that. I was a writer. I had to write.

As a full-time student (and mother), I could only work ten to fifteen hours a week, shuffling around half a dozen housecleaning clients on my own. I took out the maximum amount of loans to give us something to pay all our monthly bills, which I managed to keep around a thousand dollars. A Pell Grant and a small scholarship for survivors of domestic violence paid my tuition for the fall and spring semesters, but they didn’t cover the classes I took during the shorter winter and summer study periods. The tuition for those usually went on a credit card.

Since we’d moved away, Mia’s dad had declined to take her for the summers, leaving me to scramble to pay for child care. Eventually, I decided to do something that I’d promised him I wouldn’t—petition to double the amount he paid in child support. As a result, by the time I neared the end of my required classes, I’d racked up almost $1,000 in legal fees. Plus, I had $50,000 in student loan debt, and about $12,000 in credit card debt. My minimum monthly payments on the credit cards alone hovered around $300. I wasn’t sure what I’d do when I’d have to start making the $500 monthly payments for the student loans once the six-month grace period ended after the commencement ceremony.

Coraline came only a month after I graduated college in June of 2014. I drifted through the last month of my pregnancy with an aching pelvis, interviewing for legal assistant positions I didn’t get, the large balloon of a belly going unmentioned but not, apparently, unnoticed. In the meantime, my rejection from the college’s MFA program meant that I had to somehow grow my own platform for my writing, working on a memoir, collecting bylines as a freelance writer, hoping the followers would come.

To start, I looked for jobs that required writing or editing. I found two—one as an intern for the local YWCA, writing op-eds, blog posts, and letters to the editor, and another editing events on the community calendar. My income drifted between $500 and $800 a month. In the meantime, I had won my case for increased child support for Mia, but I’d depleted my savings in the process. We had a little less than enough to pay the bills, so I went on shuffling payments from one credit card to the next. But at least I could work from home, with Coraline drifting from nursing to sleeping to fussing on my lap. I took only two days off work after she was born but, I reminded myself, I was getting paid to write. I was a working writer.

We lived in the oldest house in Missoula in a converted apartment on the ground floor. A plaque out front named it “The Worden House,” and tourists stopped to take photos of its chipped white paint and sagging porch. Built in the late 1800s, it had evolved to four apartments and an office where the owners sold season ski-lift tickets for hundreds of dollars each—though none of that money seemed to go into improvements on the property. Our space was the largest, but the kitchen area had only two cupboards, a small fridge, and a stove with a rolling microwave cart for counter space. That summer, beneath the room that the girls and I shared, the stray cat who’d lived in the basement died during a week when temperatures climbed to a hundred. That section of the house had no insulation under the floor. I lay in bed at night, breathing in the stench.

Though at that time of year, the temperature inside often remained at eighty degrees even at night, I knew that in only a few months I’d fail to keep the space above sixty. The curtains would sway as the winter winds blew in. My landlord offered nothing to help insulate us from the cold.

“Maybe we need to discuss if this apartment is suited for your family,” he wrote in an email. When I told him I didn’t have a choice, he asked me to sign a new lease that prohibited me from having roommates. He claimed not to know that I sublet the only bedroom to classmates or friends for a small amount in exchange for help with child care. He told me to sign the lease and pay the full $875 a month on my own, or move out within thirty days.

Missoula’s population numbers about 70,000, but it fluctuates between college semesters and summers. Many college students have the privilege of parents who pay their rent, which raises housing costs and widens the gap between local wages and the cost of living. When I started looking for low-income housing assistance, most organizations had little to no funding and long wait-lists. For someone in Missoula to get a Section 8 voucher, the federal housing assistance program, the wait was three to five years (it can be much longer in bigger cities), and for any emergency housing I’d need an official eviction notice from my landlord. Many low-income housing complexes still wanted at least $800 for a two-bedroom apartment, plus first and last month’s rent, and a deposit.

For two months, in between hours that I worked or cared for my children, I walked to property management offices, talked to several caseworkers for housing assistance, and faced a dozen landlords who gave me a half-hearted grin once they saw I expected to live with an infant and seven-year-old in a studio. “This space is better for students,” they tried to tell me. Even for the spaces above neighbors who smoked, whose floors were stained permanently brown with dirt and grease, but would still cost me at least $700 a month with utilities.

“I had to keep anything from getting to me then,” I told my therapist recently, when she asked if I’d experienced any kind of post-partum depression after Coraline’s birth. “I couldn’t allow myself to cry, or I’d cry all the time.”

“Depression can appear in different ways,” she said. “Sometimes people shut down and become numb.”

“I wasn’t depressed,” I said, carefully, trying not to clench my teeth. “I was just really tired.”

I knew I was exhausted at the time, but what I could never admit to myself was how lonely I was. Maybe I could now. I guess I just did. Loneliness meant rejection; I believed that I was alone for a reason. Loneliness meant I’d failed at doing everything on my own. Loneliness meant that I needed affection, wanted company, or a partner, but all of those things felt impossible to obtain. I tried not to want, and closed my eyes to scenes of fathers holding happy children on their shoulders. I didn’t scroll through social media on holidays. Instead, I kept up the façade that we were happy, my children were happy, and sometimes we even went out and did things.

Perhaps because of my bone-aching fatigue at the time, I have very few memories of Cora’s first few months. The room we slept in was built to be a living room, with its large fireplace and bay window. A door to the common area, with a washer and dryer from the Seventies, was mostly glass and didn’t have a deadbolt. Panes of glass also flanked the lock at the back entrance by the alleyway, where people slinked home at night. Once, I’d woken up to hear someone roughly twisting the doorknob, knocking angrily on the door, yelling at me to let him into his house—too drunk to know he didn’t live there anymore. More recently, I opened my eyes to several flashlight beams crossing through windows of our bedroom, leaving shadows of large figures on the pull-down blinds, the kind that snap off their holders if you let go of them after tugging. Someone spoke into a radio. They were cops, not burglars, but that didn’t exactly ease my mind. Long after the police left, I wondered what they had been looking for.

I was getting so little sleep worrying about what would happen if there was a break-in. I hadn’t properly washed in days because the baby screamed whenever I put her down. I felt spongy, and none of my clothes fit. When Coraline’s diaper exploded and I had to change it on a table in a public bathroom, keeping one hand on her while fishing in my purse for wipes, a shirt, a plastic bag for dirty clothes, and new pants, my exhaustion and frustration grew to anger, and I’d yell at Mia to stop playing with something on the floor. I needed help and knew I wouldn’t get it. I was all I could depend on, and I had failed myself. I’d look down at the baby on the table and fight the feeling of regret for bringing her into the world.

At those moments, I would have given anything to be able to walk away. I wanted to tap out. I wanted to hand her over to her other parent, the one she didn’t have, so that he could handle it for a while. I wanted a break I was certain I’d never get, and it was hard to want something so badly, especially when it’s another human. A partner. Wanting something like that, in the way that I did, made me feel desperate. A person, I was certain, nobody wanted to date.

“I just can’t give you what you need,” one man had said to me, the last one I’d allowed myself to really like. And that was when it was still just Mia and me.

“I never asked for anything,” I reminded him, even though I knew he was already gone.

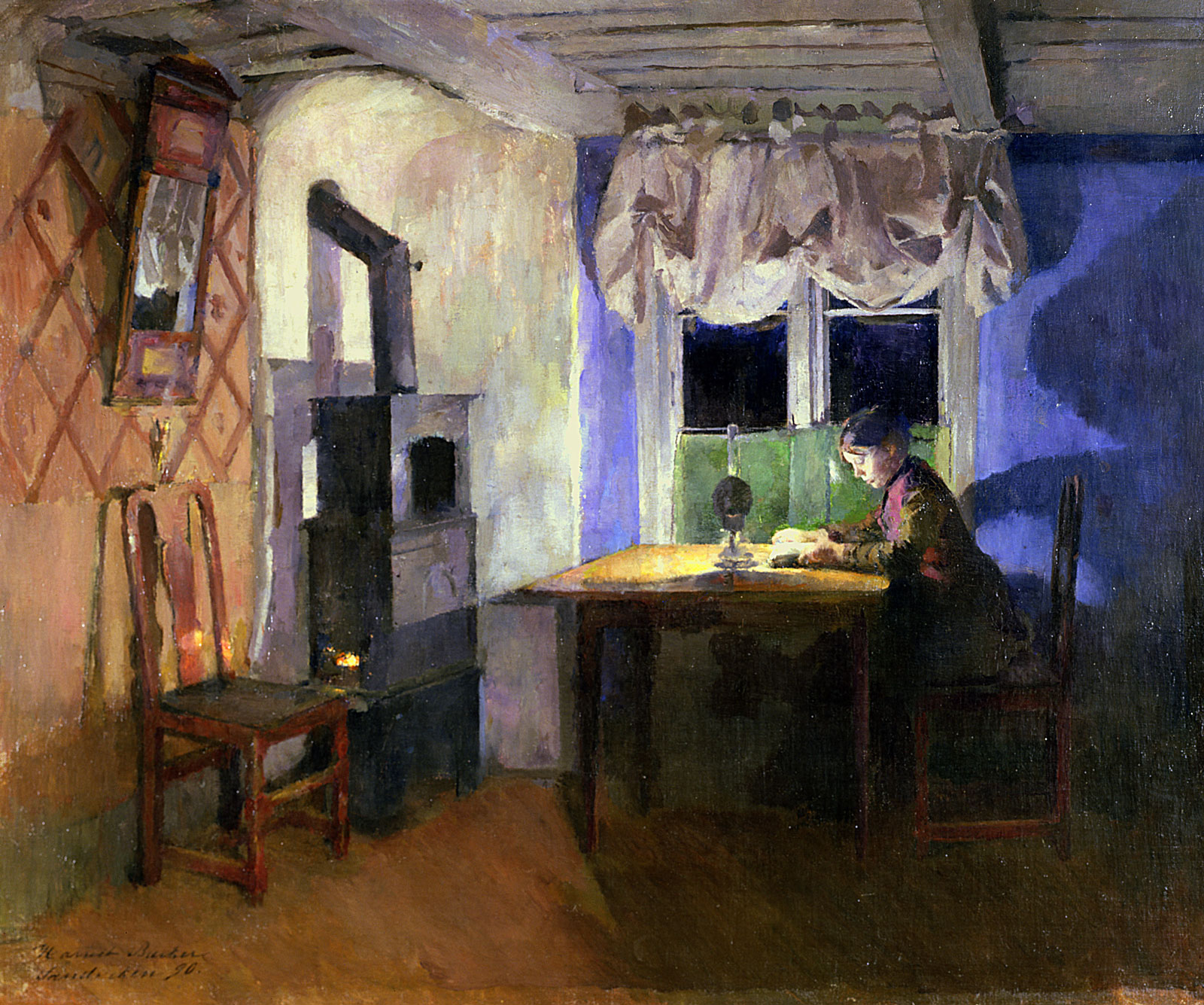

Most of the guys I dated just wanted sex, and that was fine. Sometimes, that was all I wanted, too. I liked the affirmation, the reassurance, that I was still someone who could be desired. When I just had Mia, all of that was easily attainable. She could spend the night at a friend’s house so I could go out, be free, maybe even see a band and drink beer. Coraline was different; she wouldn’t let anyone else hold her. When she was around a year old, I tried a few at-home daycares, even one lady who was known as “The Baby Whisperer.” Cora screamed so hard that she upset the other children. It wasn’t until she was nearly eighteen months that I could leave her for a couple of hours, to escape to a café down the street to work. Up until then, I worked, writing until two or three in the morning for blogs and websites aimed at single moms, sitting on the living room floor, my laptop teetering on a footstool, Cora sleeping in my lap.

In one important way, though, we had caught a break. My name had, miraculously, risen to the top of a wait-list through the Missoula Housing Authority for their Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program. We were offered a 600-square-foot apartment with two windows that faced north and saw barely any sun. But I could afford the tiny bedrooms and bathroom, and washer and dryer, on my own. Still, the anxiety followed me: it took weeks before I didn’t wake up to every sound in the night. Coraline continued to constantly orbit around me, while Mia often ran over to play at the neighbor’s. That apartment released me from housing insecurity, but the crushing sense of hopeless loneliness was always near. I felt it when I opened my eyes in the morning, and I felt it when I closed them at night.

In between, I worked. Sometimes up to sixty hours a week. I was learning that everything that happened in my life could be turned into Internet content for pay. Most often, I had up to thirty different pieces in varying stages: from pitch, acceptance, edits, or queued for publication, to invoice and payment. That’s what being a freelance writer requires in this economy, if you want to sustain a livable income.

It took two years, but I wrote my way off food stamps. Things started to look up. I got my first smartphone. I traveled to speak on panels and attend conferences about social and economic justice—the subjects I was starting to become known for writing about. When the book deal came from an essay I’d written about cleaning houses, I hung up the phone, stood in my living room, and felt the air expand around me. Mia was at day camp, and Cora was in daycare. I’d need to go pick them up in thirty minutes.

I closed my eyes, breathed in and out for five counts. It had been my life’s ambition since I was ten to publish a book, and there it was. I wanted to scream, jump, cry. I wanted someone to do that with me. Instead, I opened my eyes, grabbed my wallet, and walked out the door. It was Coraline’s birthday. We needed cupcakes to celebrate.

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.