In November 1989, as the Berlin Wall was coming down, a KGB officer stationed in Dresden was hurrying to destroy thousands of secret documents inside the agency’s compound. He later recalled that East German citizens were trying to overrun the facility as he shoveled top-secret files into the fire so quickly that the furnace burst. A decade later, that KGB officer, who considered his service to the Motherland a sacred sacrifice born of devout patriotism, became the leader of all Russia: President Vladimir Putin.

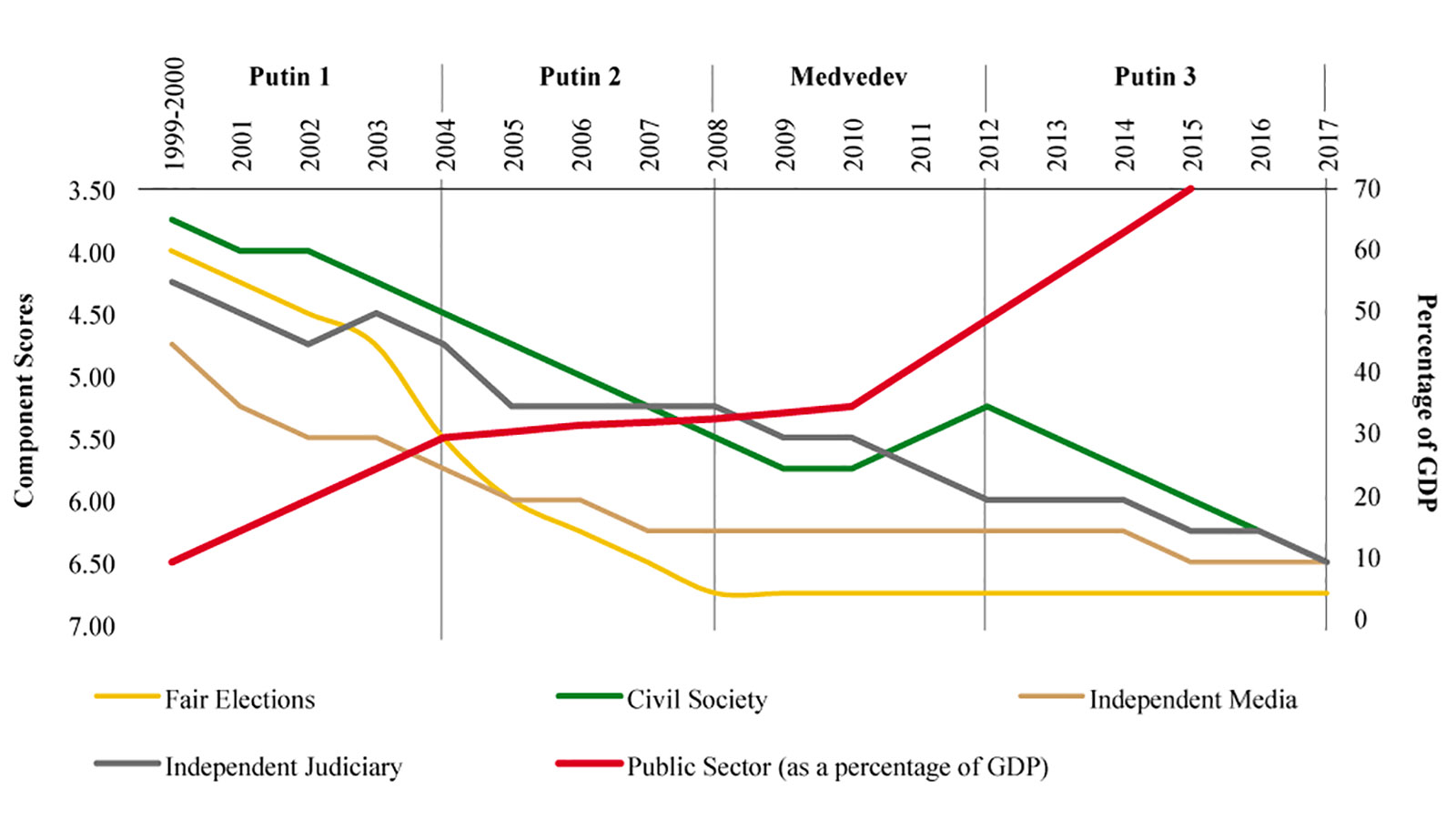

Putin was relatively unknown outside of Russia when President Boris Yeltsin surprised the world on New Year’s Eve, 1999, by resigning and appointing Putin as his immediate successor. Inside Russia, though, Putin had advanced to the highest echelons in the state security apparatus, renamed the Federal Security Service, or FSB. In his inaugural New Year’s presidential message, Putin assured Russian citizens that “freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, freedom of the press, the right to private property—all these basic principles of a civilized society will be reliably protected by the state.” His actions soon suggested otherwise. Russia was then ranked higher than China on Freedom House’s civil liberties score, about level with Brazil, and was approaching parity with India—all considered members of the “BRIC” group of emerging-market countries. Russia’s private sector had grown to 89 percent of the economy; the public sector accounted for only 11 percent of GDP; these are figures worth remembering.

Putin’s real intention—and not from the day he entered the Kremlin, but from the day he left Dresden—was to reassert the authority of the autocratic state. In the years to come, he made no secret of the fact that he considered the demise of the Soviet Union to be the greatest “geopolitical catastrophe of the [twentieth] century.” In 1992, while working for the mayor of St. Petersburg, he hired a production company to make a film about himself so he that could reveal his past in the reviled KGB in a way that would be palatable to the public and protect his political ambitions. The title of the film was Vlast, or “Power.” Vladimir Putin was going to make Russia great again.

He went about it by methodically appointing longtime loyalists from the Russian security forces, military, and powerful ministries such as Interior Affairs and Defense, to important positions in government and industry. This sort of heavy reliance on personal networks dates back to tsarist and Communist periods in Russia, when connections were essential for supporting nearly every aspect of daily life. This clannish proclivity has shaped Russia’s culture and Putin’s psyche. The mix of high-ranking officials in Putin’s inner circle is collectively referred to as the siloviki, a term that conveys power with the ultimate authority to secure compliance. Despite Putin’s market-friendly rhetoric, designed to instill confidence in global investors, his immediate strategy was to steer Russia away from its nascent market economy to a state-capitalist oligarchy.

The independent media was Putin’s first target. Newspapers, and TV and radio stations, often funded by wealthy oligarchs, were playing an increasingly important part in Russian politics by the late 1990s. One media organization in particular, NTV, had attracted Putin’s ire by airing a satirical puppet show ahead of the 2000 presidential election in which a Putin puppet played Little Zaches, an evil changeling from a fairy tale by E.T.A. Hoffman. In Hoffman’s story, the people of a village are so manipulated by Zaches that they mistake him for a gentleman and scholar, and award him the job of minister to the prince. Putin’s supporters reacted fiercely to the caricature; a letter was published in St. Petersburg’s Vedomosti newspaper signed by the rector of St. Petersburg State University, calling for charges to be brought against the producers of the show.

Shortly afterward, government raids began on NTV’s parent company, Media-MOST, which had been created by Vladimir Gusinsky, one of the few oligarchs in Russia to have built his fortune largely by his own efforts rather than through the corrupt privatization schemes of the 1990s. When Gusinsky himself was arrested in June 2000, Media-MOST included NTV, NTV+, and TNT television channels, as well as Sevodyna, Russia’s first independent daily newspaper. Gusinsky was placed under house arrest until he agreed to sell Media-MOST to Gazprom, the state’s natural gas monopoly, for $300 million. The final transaction came to be known as Gusinsky’s “shares for freedom” because the contract guaranteed that the government’s charges of embezzlement would be dropped against him if he signed. Gusinsky did so and fled to Spain, but later declared the deal null and void because he had been forced to sign under duress.

Advertisement

With Gusinsky in exile, the Moscow Arbitration Court froze his stake in Media-MOST as collateral for an unpaid loan he supposedly owed to Gazprom, giving majority control of his media holdings to Gazprom. Three months later, Gazprom forced a change in management at NTV and many of the leading journalists left. Within two years, the two channels that had absorbed most of the journalists, TV-6 and TVS, were closed by the authorities.

As for Gusinsky, the Russian government filed fraud charges against him in Spain, which led to his being placed under house arrest again. After several months, a Spanish high court threw out the charges and refused to extradite him. Gusinsky left Spain for Israel, where Russia again brought charges against him, this time for money laundering, but Israel refused to arrest him. Gusinsky then moved to Greece, where Russia filed similar charges, and he was arrested in Athens. Only after a Greek court refused Russia’s request to extradite him did Russia finally give up its efforts.

By then, the Kremlin had turned its attention to a bigger prize, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the owner of Russia’s largest oil company, Yukos Oil, and the richest man in Russia. Khodorkovsky was arrested for tax evasion and fraud, and later sentenced to ten years in a Siberian prison. The largest subsidiary of Khodorkovsky’s Yukos Oil was eventually sold in a sealed bid auction to a bogus shell company that was purchased a few days later by Rosneft, a competing oil firm whose boss, Igor Sechin, was also serving as deputy chief in Putin’s administration.

By the end of his second term in office, in 2008, Putin had altered the criteria for judges serving on the Qualification Colleges that can dismiss judges from their posts, a move that enabled him to pack this oversight body with his appointees. He had also signed an edict extending his executive powers over all law enforcement and securities agencies, and made several watchdog bodies subordinate to the very ministries they were meant to monitor. Meanwhile, his political party, United Russia, had abolished elections for regional governors and replaced them with a system of presidential appointments—any of which could be rescinded by the president if he deemed a governor to be disloyal. Russian autocracy was back.

According to Bill Browder, author of Red Notice and the driving force behind the US Magnitsky Act, the richest person in Russia during the Soviet period was only about six times richer than the poorest. By the time Putin assumed the presidency in 2000, the richest oligarch in Russia was 250,000 times richer than the poorest citizen. The disparity in wealth that developed during the Yeltsin administration, and the widespread perception of corruption, galvanized support—ironically enough—for Putin’s series of hostile corporate takeovers. By the end of his second term as president, he had pushed through the Strategic Sectors Law, which requires prior government approval of foreign investment in any one of forty-five industrial sectors deemed essential to Russia’s national security and defense, including oil, gas, minerals, and aviation.

While Putin’s pattern of corporate raiding increasingly rattled international investors, his approval ratings at home stayed consistently around 70 percent throughout his first two terms. He was admired as a ruthless leader who was reclaiming Russia’s rightful possessions and restoring her respectability in the world order. Russia’s booming economy, bolstered by oil at $132 a barrel, didn’t hurt his popularity. When the bubble burst in 2009, the economy contracted rapidly by 8 percent—and public support for authoritarian leadership faltered.

In September 2011, after serving four years as prime minister, Putin announced that he would run for a third term as president. This end run around the presidential term limit was made possible only by the great favor Putin’s former deputy from the St. Petersburg mayor’s office had done for him. During Dmitry Medvedev’s single term as president (2008–2012), he signed an amendment to the Russian Constitution that permitted Putin to run for a third term—and one that would last six years, instead of four. If Putin were to win another two consecutive terms, he would be president until 2024. The Russian public was not happy. Social media erupted with citizens voicing their disapproval and calling for new leadership.

In November 2011, one of my graduate students emailed me a link to a YouTube video. He said it was about Russia and that it would shock me. I doubted it: after following economic and political events in post-Soviet Russia for twenty years, I felt I was unshockable. I was wrong. My jaw dropped as I watched 20,000 ordinary Russians booing Vladimir Putin as he stepped into a ring at a martial arts match to introduce the fighters. A few weeks later, when the December 2011 parliamentary elections were held, Putin’s United Russia Party still won, but only by a slim majority. Multiple reports of election fraud spread quickly on social media after the polls closed, and people took to the streets in the largest popular demonstrations since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Advertisement

It was around this time that one of my closest Russian colleagues told me that he believed that the only thing that Putin truly feared was the power of “uncontrolled” social media. In the year that had then just passed, Putin had watched as, one by one, leaders of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East and North Africa were overthrown by protesters during the Arab Spring. He was determined not to allow this to happen in the streets of Moscow.

A month ahead of the March 2012 presidential election, some 100,000 Russians demonstrated in -18° C temperatures in Moscow, calling for a rerun of the disputed December parliamentary elections—to no avail: Putin won his third term. But the day before his inauguration, violent clashes erupted between police and some 20,000 protesters in Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square. He responded by signing a law criminalizing public protests without a permit. Even so, on June 12, about 70,000 brave demonstrators marched in defiance. The war between Russian civil society and the Kremlin was on. Unfortunately, it received limited attention outside Russia, much less any credible coverage on traditional media inside Russia—which the government already controlled.

In July 2012, Putin signed the Internet Restriction Law, which established a federal blacklist of websites containing any content that the government deemed “extreme.” The law permitted Roskomnadzor, the mass-media regulator, to block—without a court order—public access to any website; it also expanded a ten-year-old statute, the Law on the Counteraction of Extremist Activity, that permitted courts to issue cease and desist orders at the government’s request to media companies that published or aired material that could be damaging to an individual’s image. There would be no more satirical puppet shows mocking politicians.

Despite the growing evidence of a major crackdown, Western governments celebrated Russia’s entry into the World Trade Organization in August 2012. American analysts described the event as the last stage of Russia’s post-cold war entry into full membership in the global economic community. Foreign investment poured in, pushing Russia into the top three destinations for foreign direct investment in 2013, along with the US and China. Russia was included in Bloomberg’s Fifty Best Countries for Doing Business for the first time, and advanced twenty points in the World Bank’s Doing Business ratings. What were they thinking? By then, the Russian government owned 80 percent of the country’s ten largest companies, and state-owned banks held 60 percent of all banking assets. Public-sector employees had risen to 28 percent of the workforce, and resources that could have benefitted all workers, such as investments in healthcare or pension reforms, were redirected to raises for employees of the FSB.

Meanwhile, highly profitable businesses were being seized and transformed into state-controlled companies headed by Putin’s handpicked CEOs, the oligarchs. Several of them had just been named to a US sanctions list thanks to the Magnitsky Act, signed into law by President Obama on December 14, 2012. (The act was named in honor of Bill Browder’s Russian auditor, who was brutally tortured to death in a Russian prison after exposing an extensive tax scam inside the Russian government.) On top of all this, Putin warned in 2013 of the dangers of unbridled free speech, and signed another law that criminalized blasphemy. Insulting religious beliefs would now constitute a federal crime and was punishable by up to three years in prison.

Oligarchical capitalism destroys legitimate competition and eats away at the resources of a nation like a cancer. Any semblance of dynamic, healthy competition is strangled by fake competition based solely on firms’ relationships with people in power. When a shrinking private sector is entirely owned by the oligarchical elites, this precludes ordinary citizens from having a stake in the real economy and increasing their personal wealth over time. As the nation’s wealth becomes more concentrated in fewer hands, there is less incentive and fewer resources to resist the momentum of this disparity. The twenty or so oligarchs in Putin’s Russia do not get access to powerful people in government because of their wealth, as is the case, say, with many billionaire political donors in America, but rather the reverse: Russian oligarchs get access to obscene amounts of wealth because of their affinity with those most powerful in government. Men become oligarchs in Russia (there are no women oligarchs) because they are loyal to the only person in government who matters: Vladimir Putin.

By late 2013, Western influence was coming uncomfortably close to Putin’s western border in the form of Ukraine’s pending trade agreement with the European Union, which that country’s president, Viktor Yanukovych, was planning to sign. Driven by pride and paranoia, Putin succeeded in pressuring Yanukovych to abandon the deal in favor of closer relations with Russia. The Ukrainian people were outraged and took to the freezing winter streets in what became known as the Euromaidan Revolution. (Maidan is the name of the public square in the city center of Kiev where the largest protests took place.) After Yanukovych was deposed by the citizens of Ukraine on February 22, 2014, Putin welcomed him into exile in Russia, just as the closing ceremonies of the Winter Olympics in Sochi took place.

The ouster of Yanukovych—as a portent of what might happen to him—was a shocking blow to Putin. His approval ratings had slipped to 63 percent by the end of 2013; there was no way he would risk another round of protests in the streets of Moscow. Accusing the US of orchestrating the anti-government movement in Ukraine, he clamped down even harder on freedom of speech via social media. He enacted Russia’s so-called Blogger Law, which requires website owners with more than 3,000 hits per day on their blogs or social media accounts to register with the state as a media company and comply with all federal regulations.

When Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014, and later moved troops into eastern Ukraine, foreign investors got a shock. Foreign direct investment in Russia fell from a record high of $69.2 billion in 2013 to $22 billion in 2014. To make matters worse for Russia, oil prices had cratered, which further depressed the value of the ruble. More than half of Russia’s federal budget revenue is generated from the sales of its oil exports. Putin couldn’t control oil prices, but he already controlled the media and was able to strengthen his domestic approval rating by distributing “fake news” coverage that portrayed the US as the main aggressor among Western governments in attempting to weaken Russia through economic sanctions.

When Putin intervened in Syria to prop up its murderous despot, Bashar al-Assad, in September 2015, foreign investors in Russia hit the panic button. Foreign investment fell to $6.8 billion—a stunning 91 percent drop in two years. According to Oleg Babinov, head of Russian and Eastern European risk assessment for Risk Advisory, a global consulting firm, “the Kremlin had knowingly put Russia’s geopolitical interests above its economic ones and had deliberately driven the country into political self-isolation.” Putin’s determination to put geopolitical aims before economic interests defies rational economic thinking, but it is perfectly logical in the mind of a career KGB agent, especially one who is financially secure no matter the fate of the Russian economy. In a 2000 documentary, Yevgenia Albats, the editor of The New Times magazine, explained that KGB officers were indoctrinated with derzhavnik, the belief in Russian greatness, and “Everything else—democratic institutions, personal liberties, personal freedoms, individuality, human rights—everything [else] is after this.”

After Putin’s nemesis, Hillary Clinton, lost the US presidential election to Donald Trump, global investors sensed that relations between Russia and the West might warm, and began to cautiously move their capital back to Russia. Foreign investment rose again, to $32.5 billion for 2016, but the optimism was short-lived. Once US intelligence agencies confirmed that there had been Russian interference in the 2016 election, and Robert Mueller was appointed as special counsel to lead a Justice Department investigation, there was no way that Trump could remove American sanctions against Russia; Congress made sure of that. The Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, set in motion to punish Russia for US intelligence agencies’ finding that it had interfered in the 2016 general election, was passed in July 2017 by a 98-to-2 vote in the Senate. Though he complained that the law was “seriously flawed,” Trump signed it on August 2 and started a six-month clock ticking.

The US secretaries of treasury and state and the director of national intelligence had until February 1, 2018, to sanction individuals doing business with Russian intelligence and the military, and to identify oligarchs with close ties to Putin for possible sanctions. Ahead of Thursday’s deadline, The Moscow Times reported that “Russia’s wealthiest individuals are busy hiring lawyers and searching for lobbyists in Washington.” Herman Gref, the CEO of Russia’s largest state-owned bank, Sberbank, went further and flatly called Trump’s bluff. He told the Financial Times that he believed there was little chance the US would actually impose harsh sanctions on Russia’s oligarchs and state-owned corporations. But if it did, he warned, the consequences “will make the cold war look like child’s play.”

Trump seemingly buckled to the pressure, and folded. On January 29, the Treasury Department issued a list of 210 Russian government officials and oligarchs, without applying any sanctions on the individuals. A former treasury official characterized the action as nothing more than a mechanical fulfillment of the deadline, while a current one confirmed that the unclassified list was sourced in large part from a Forbes magazine list of the “200 richest businessmen in Russia 2017.” Secretary of State Rex Tillerson further angered members of Congress by announcing that the State Department would not impose sanctions on companies doing business with the Russian military and intelligence agencies, as required by the law.

Some experts believe the “naming-and-shaming” list could be problematic for Putin and the oligarchs, coming on top of the leaked Panama Papers’ revelations about his personal plunder of Russian riches. According to reports, the documents revealed “a network of secret offshore deals and vast loans worth $2 billion has laid a trail to Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin” (typically, bogus shell companies in places like Cyprus or the Isle of Man). The Europe-based Centre for Economic Policy Research estimates that the financial assets held abroad by Russian oligarchs in offshore entities equal the total wealth of the entire Russian population held inside Russia. The analysis chimes with Bill Browder’s assessment, in testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee in July 2017, that Putin has made himself “the richest man in the world,” with a net worth of $200 billion.

While Russia’s unemployment rate is down to 5 percent and inflation is at a record low of 2.5 percent, the public sector now accounts for 71 percent of the moribund economy, which is forecast to grow at a sluggish rate of only 1.5 percent per year over the next six years. More than half of Russians believe they are living in poverty, according to a 2017 survey by Russia’s Higher School of Economics—a percentage three times higher than the official poverty rate.

The war between civil society and the Kremlin is not over. Last weekend, thousands of demonstrators rallied in cities across Russia to protest the prospect of Putin’s fourth presidential term. “Six more years? No thanks!” read one placard, and protesters chanted “Putin is a thief.” But their voices are few, and it is easy for the authorities to stifle dissent. Today, Russia ranks lower on the protection of civil liberties than Myanmar, Pakistan, and the West Bank. With the Kremlin’s transition to kleptocracy, the oligarchs’ betrayal of their country is complete. Far from being the patriot he poses as, Putin is a parasite who has sucked his fortune out of Mother Russia.