To celebrate The New York Review’s fifty-fifth anniversary, we are featuring one article from each year of the magazine’s history. Today we revisit the late Eighties: Oliver Sacks on an extraordinary artist, Italo Calvino on rereading the classics, Ronald Dworkin on the Bork nomination, Joan Didion on the press and political campaigns, and Timothy Garton Ash on the fall of the Berlin Wall.

1985

The Autist Artist

Oliver Sacks

“Draw this,” I said, and gave José my pocket watch. He was about twenty-one, said to be hopelessly retarded, and had earlier had one of the violent seizures from which he suffers. His distraction, his restlessness, suddenly ceased. He took the watch carefully, as if it were a talisman or jewel, laid it before him, and stared at it in motionless concentration.

1986

Why Read the Classics?

Italo Calvino

The classics are books that exert a peculiar influence, both when they refuse to be eradicated from the mind and when they conceal themselves in the folds of memory, camouflaging themselves as the collective or individual unconscious.

1987

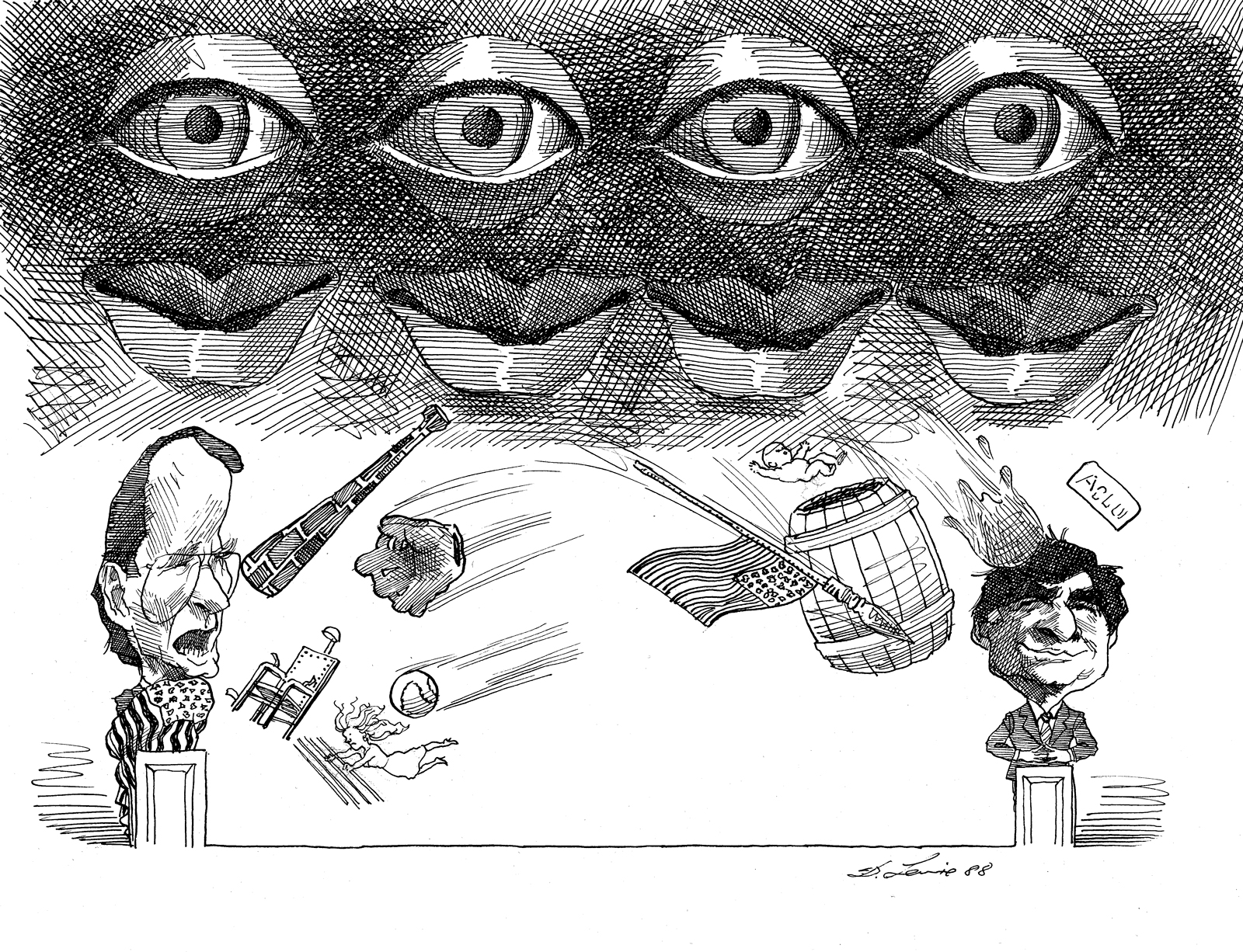

The Bork Nomination

Ronald Dworkin

It would be improper for senators to reject a prospective justice just because they disagreed with his or her detailed views about constitutional issues. But the Senate does have a constitutional responsibility in the process of Supreme Court appointments, beyond insuring that a nominee is not a crook or a fool.

1988

Insider Baseball

Joan Didion

It occurred to me, in California in June and in Atlanta in July and in New Orleans in August, in the course of watching first the California primary and then the Democratic and Republican national conventions, that it had not been by accident that the people with whom I had preferred to spend time in high school had, on the whole, hung out in gas stations.

1989

The German Revolution

Timothy Garton Ash

Everyone has seen the pictures of joyful celebration in West Berlin, the vast crowds stopping the traffic on the Kurfürstendamm, Sekt corks popping, perfect strangers tearfully embracing—the greatest street party in the history of the world. Yes, it was like that. But it was not only like that, nor was that, for me, the most moving part.