Childhood in France:

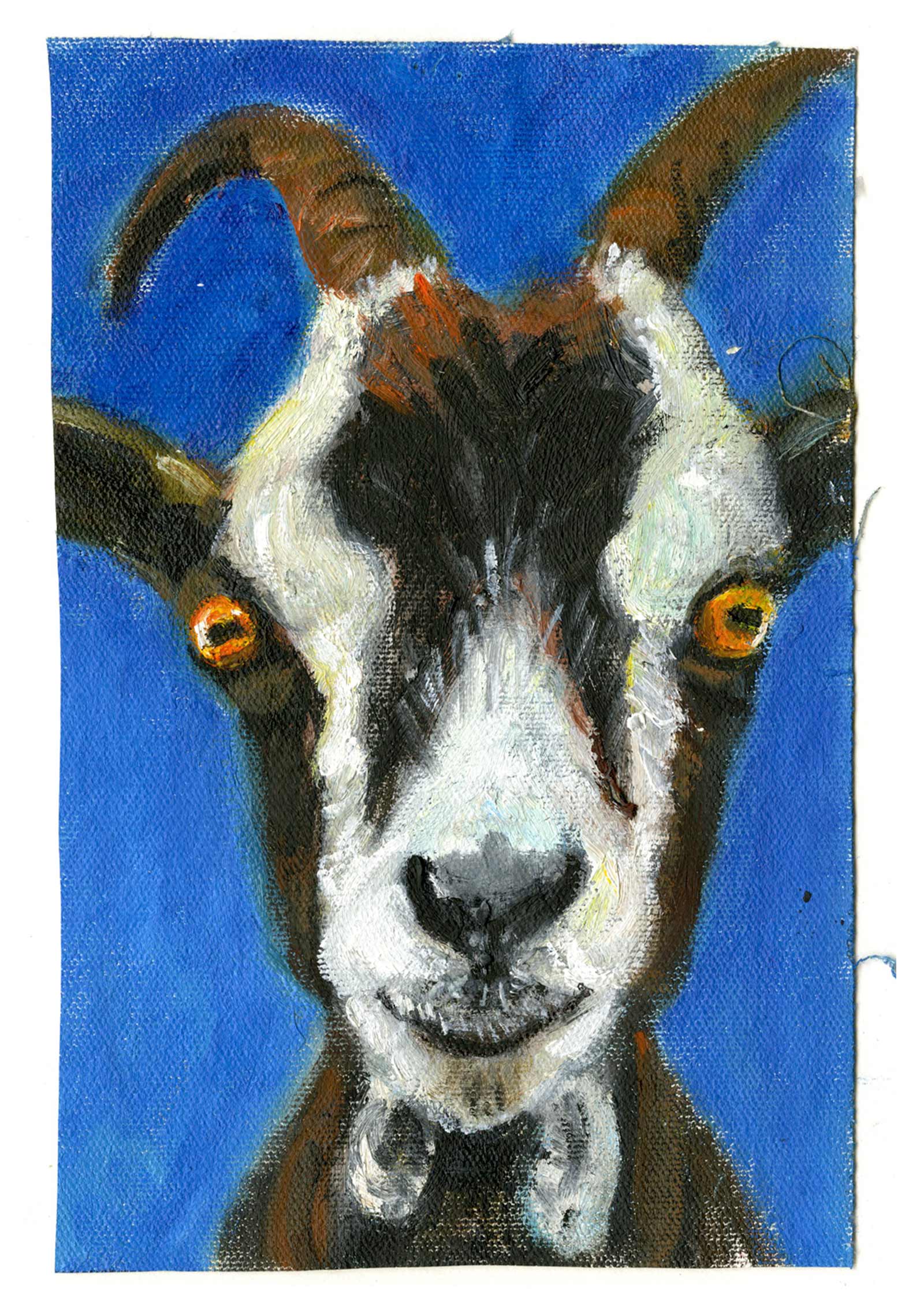

When I was a little girl, I used to spend my summers in a village on the French Riviera, staying with my aunt Mada and an old Russian lady who raised goats and rabbits. She only spoke Russian and so did her goats. I soon learned the words you need in order to tell a Russian-speaking goat to go left or right—though there was something absolutely contrary about these goats, and likable as they might be, if you wanted them to go left, you had to say, “Go right!” and vice versa. I was told my Russian accent was terrible, but the goats seemed to understand anyway, and always went the right way.

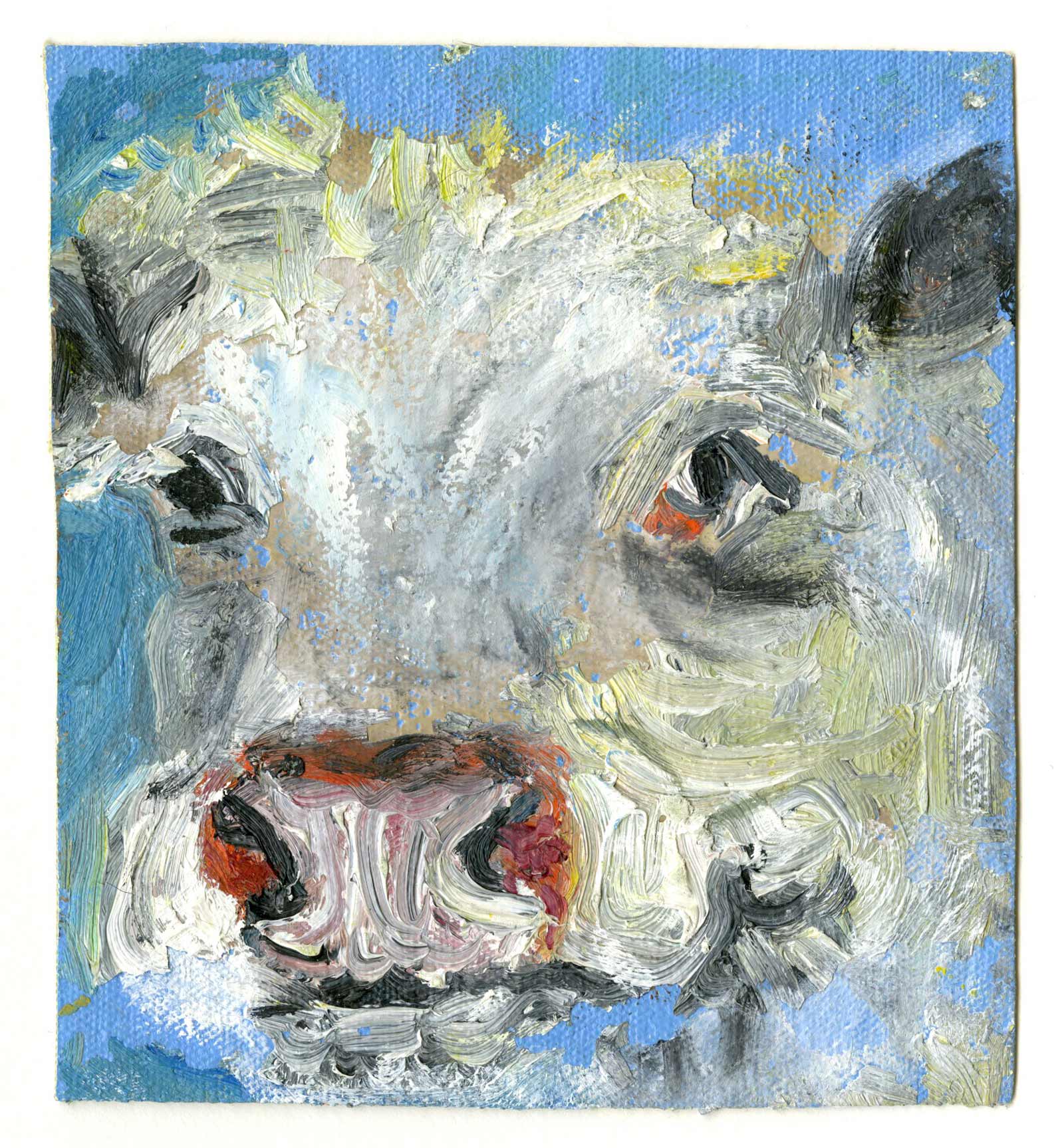

Except for the fact that they are always clucking and flapping about, hens are not devoid of a certain shapely elegance. Some hens, in fact, are downright beautiful. If I lived in the country, I might like to keep a few hens and give them French names. Then, every morning, I would go looking for fresh eggs to eat “à la coque,” boiled and with a little salt, the way I did when I was young.

Summers in Vermont:

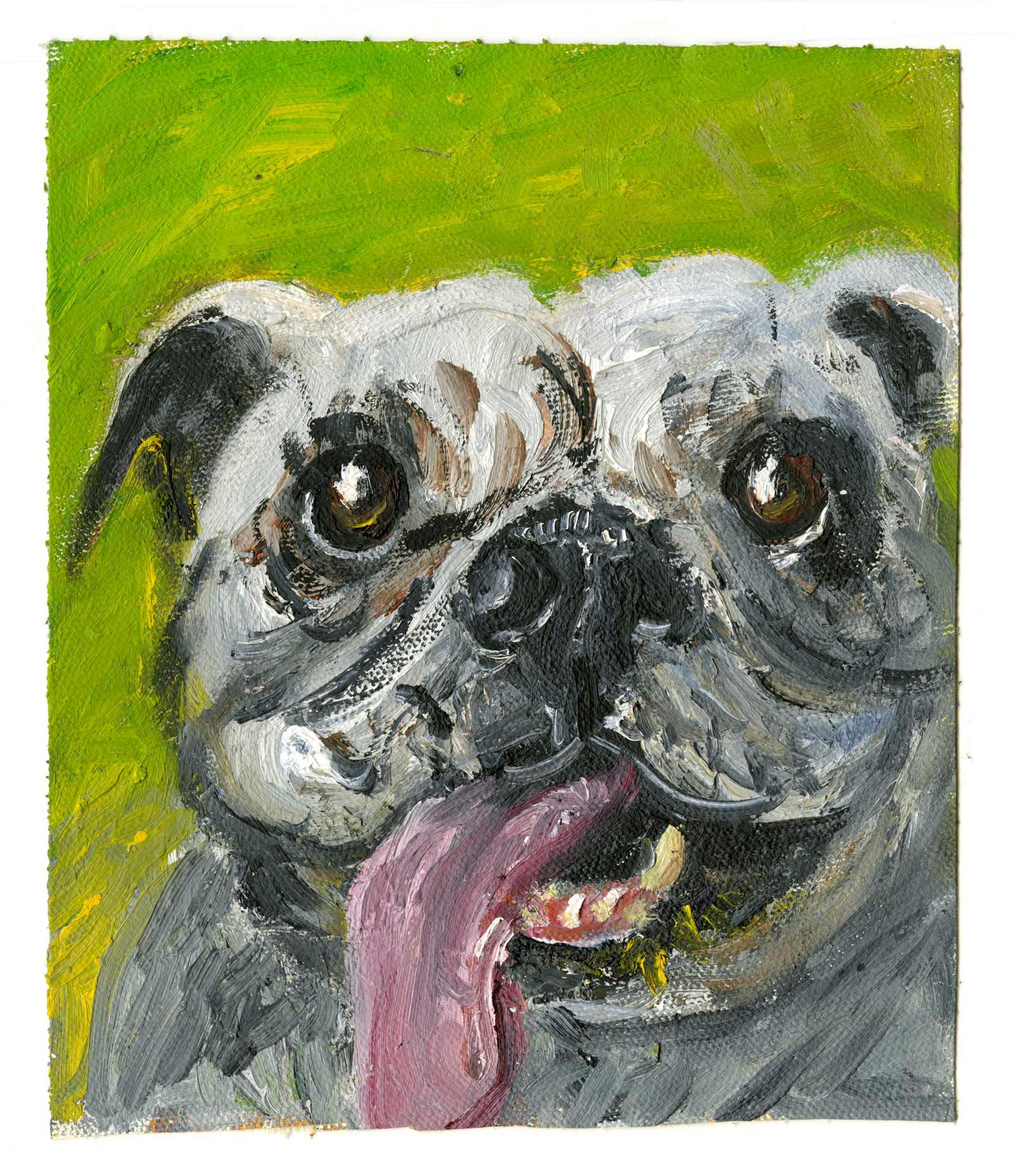

One day, a big white dog came lolloping down the meadow where I was painting in Vermont, and, with a contented sigh, settled himself right between me and the easel. I couldn’t continue without stumbling over him or splashing him with paint. And if I moved my easel, he moved with it. There was nothing to do but surrender and pack up for the day. The dog observed my defeat with a funny look—disdainful or disappointed, I couldn’t tell—and then lolloped off again without a backward glance. I never saw him again.

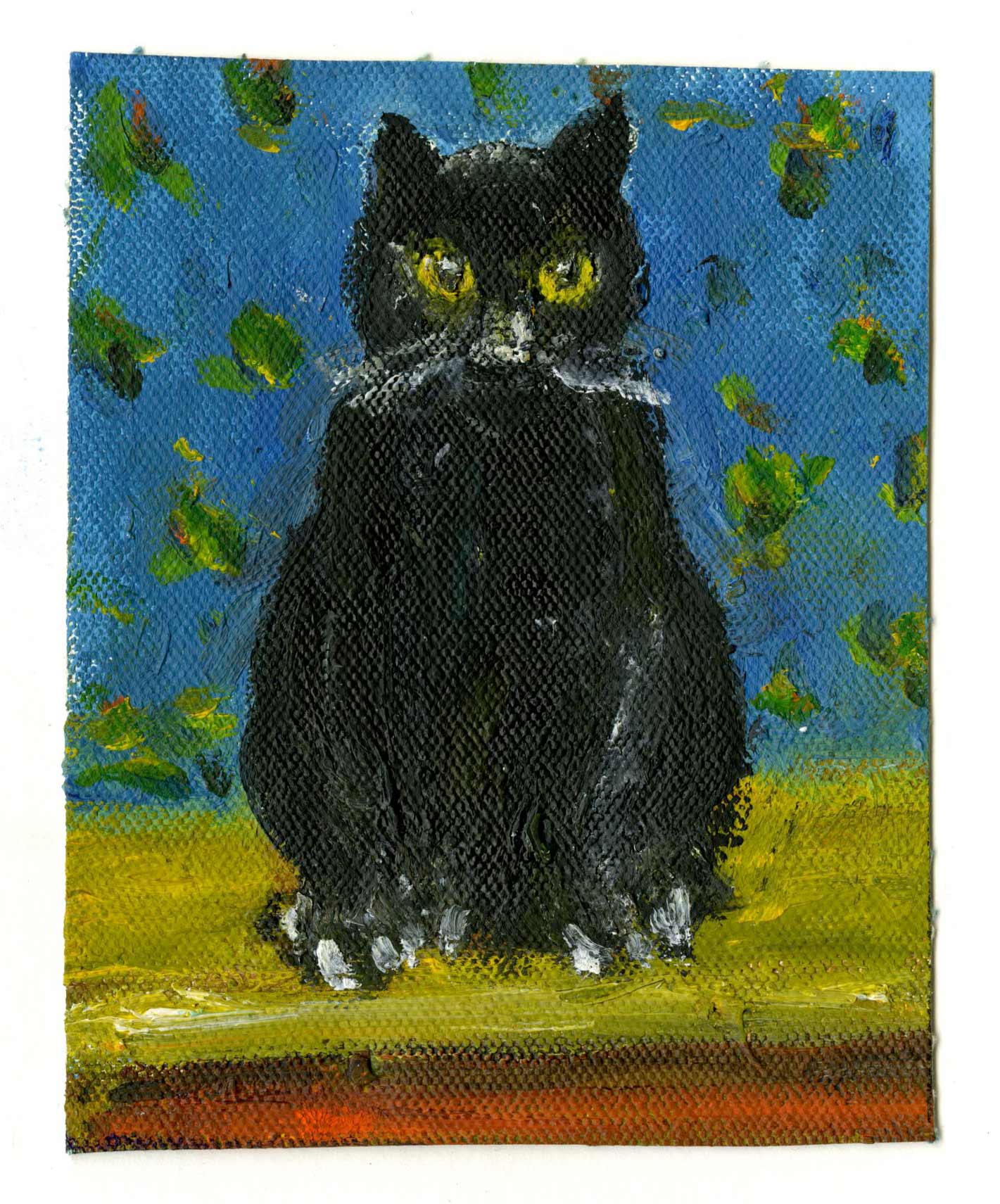

For years, we left New York to spend the summer in northern Vermont, where we had a cabin. One summer, a cat named Booties, which belonged to some folks in the village, got into the habit of visiting us daily. He appeared at the top of the road, then walked in leisurely fashion through our door. We were always delighted, even somewhat honored, to receive his visits. I have never known a more personable cat. He was very smart and dignified; our whole family was crazy about him. The next summer, when we came back, Booties was gone. He’d been killed by a car that winter, we were told. I was always forgetting he was gone, and kept looking toward the top of the road, expecting to see him.

Occasional meetings:

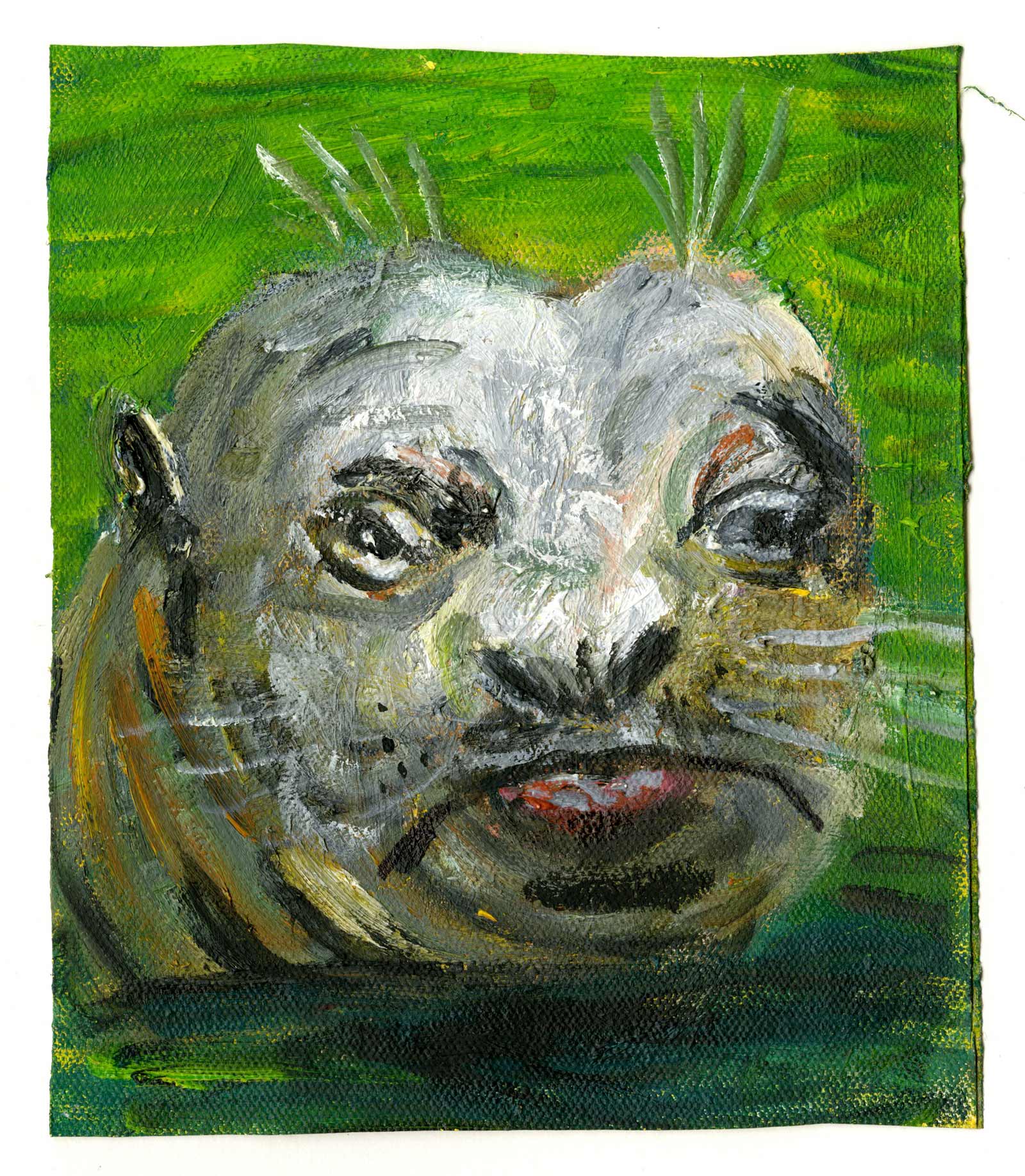

This seal belongs to the Brooklyn Zoo. She barks like a dog and even looks a bit like a dog. She also looks like an old man—Winston Churchill, specifically—and depending on her expression, like another, more contemporary politician who will remain nameless. She is a fantastic swimmer. She catches small fish and the children love to watch. Altogether, she seems content enough with her life, if a bit pensive.

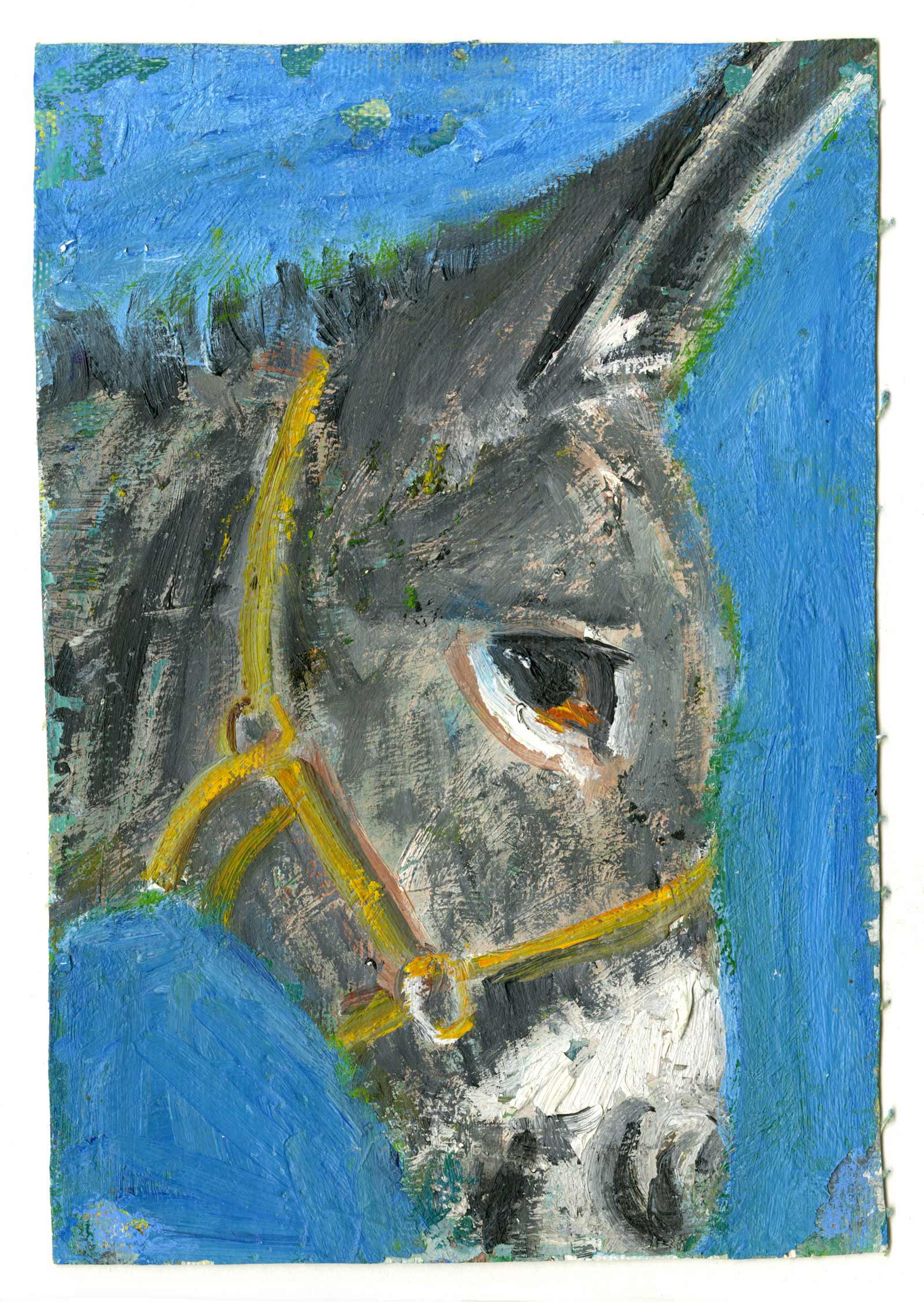

In his Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (1879), Robert Louis Stevenson described a donkey better than anyone ever had. Modestine, as she was named, “was patient, elegant in form, the color of an ideal mouse, and inimitably small. Her faults were those of her race and sex; her virtues were her own.” I have always liked donkeys. I like how they look and I love to paint them. (I find donkeys, goats, and cats best to paint in general.) If I were an animal, I probably would not want to be a donkey as most of them have pretty rotten lives, but I feel that of all the animal kingdom, donkeys are my landsmen, my kin, and chances are I would be one.

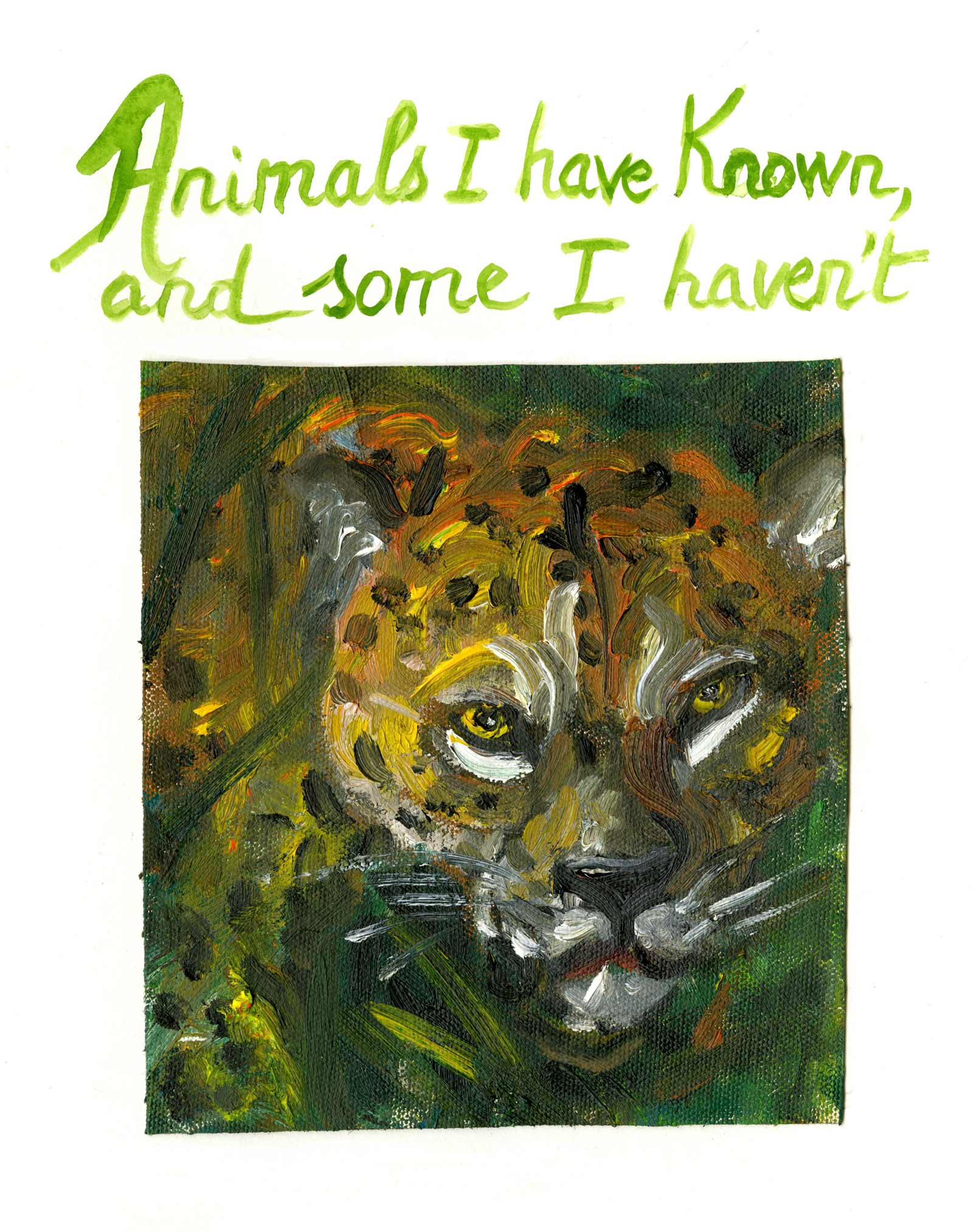

Fabulous creatures:

There is something self-assured, brave, even gallant, about this bird. It doesn’t care what you think. All you need to know is that blue-footed boobies live on the coasts of Central and South America, mostly the Galapagos Islands. I have never met a booby in the flesh, but I would recognize one at once if we ever crossed paths.

There is something self-assured, brave, even gallant, about this bird. It doesn’t care what you think. All you need to know is that blue-footed boobies live on the coasts of Central and South America, mostly the Galapagos Islands. I have never met a booby in the flesh, but I would recognize one at once if we ever crossed paths.

The wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood” is not very smart. Why can’t he just eat Red Riding Hood right there in the woods? Why all the rigmarole about running to Grandmother’s house, and worse yet, donning her cap and nightgown? It’s completely unrealistic! Wolves are dignified and proud—but dangerous, too: you wouldn’t want to meet a pack of them as you crossed the frozen steppes of Russia alone in a troika. But from afar, there is much to admire about this untamed and beautiful beast.

Between France and America:

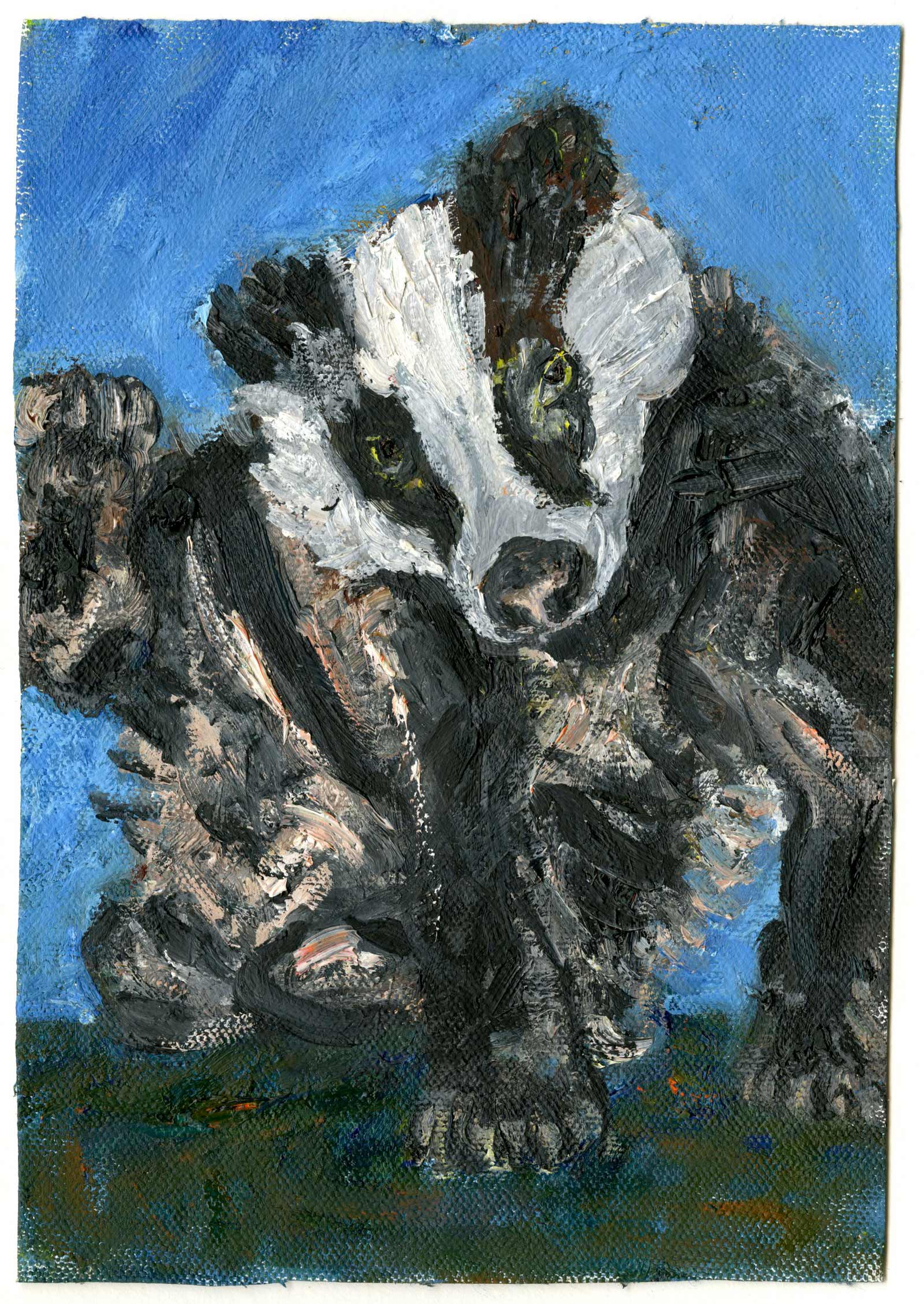

I found this portrait of a young badger the other day, and I thought he looked so appealing I decided to consult my French-English dictionary to see what this interesting animal was called in my native French: blaireau! Well, of course, I knew what a blaireau was, just as I knew what a badger was. But I hadn’t thought of either one in a long time, and I had never put the two together. Will the wonders of language and nature never cease?